Stress-Related Growth: Building a More Resilient Brain

The concept that challenging life events have the potential to facilitate positive change has been explored for centuries in the areas of philosophy, theology, and the arts. However, scientific examination of stress-related growth (SRG) started in the 1990s (posttraumatic growth [PTG], thriving, finding benefits, adversarial growth) (20–24). Research over the past half-century has also established that high levels of stress increase risk for development of both psychiatric and medical conditions (25). The growing recognition that individual outcomes following exposures to challenging events are quite diverse (i.e., ranging from highly detrimental to highly beneficial) led to the development of resilience as a broader framework (5, 7, 26–28). In this context, resilience is conceptualized as a dynamic multifactorial process presenting multiple possibilities for improving outcomes (e.g., SRG)

The resilience cycle (Figure 1) encompasses ongoing interactions among a complex array of biological (e.g., genetic, epigenetic), neuropsychological (e.g., cognitive, emotional), and environmental (e.g., social, economic, and cultural) factors that affect how an individual responds to a particular stressful experience (3–9, 26–30). A resilient (hardy) individual maintains an adaptive level of physiological and psychological functioning when challenged by events. Multiple types of evidence support the importance of moderately stressful events (tolerable stress) for increasing an individual’s level of resilience (stress inoculation, tempering, steeling, adversity-driven resilience) (1–5, 7). Events that induce little or no stress do not provide a resilience-building experience. Events that induce very high levels of stress may overwhelm an individual’s coping capacity, at least temporarily (toxic stress). It should be noted that SRG has been identified not only in relation to stressful or traumatic external events but also in relation to recovery from serious mental illness (31, 32). A personal account of recovery from psychosis noting psychological growth following several psychotic episodes suggested that opportunities for growth (e.g., intentional introspection, meaning making, benefit finding, and positive self-disclosure) should be intentionally incorporated into treatment and recovery plans (32).

FIGURE 1. The baseline level of resilience (initial state) is a product of complex interactions among multiple biological, psychological, and environmental factors that play a key role in an individual’s response to a stressful event (1–9). The adjustment process and the outcome also depend on the severity of stress experienced. If a stressful event is of moderate severity (tolerable stress), successful adjustment may increase resilience and promote growth (green). Events that induce little stress require little adjustment and thus are likely to result in recovery (yellow) without increased resilience (i.e., return to baseline functioning). Events that induce very high levels of stress (toxic stress) may overwhelm an individual’s coping capacity, at least temporarily, and result in impairment (red). Resilience level is modulated by many factors, including aspects of cognitive flexibility (e.g., deliberative rumination, finding meaning, reappraisal, self-reflection, and internal locus of control) and emotion regulation (e.g., suppression of emotion, emotional disequilibrium, and emotional hyper reactivity) (4, 8–12).

Although most research to date has focused on the construct of posttraumatic growth, this is only one aspect of a rather complex and multifaceted phenomenon of positive adaptation and development following events that are perceived as distressing regardless of valence (4, 28). An emerging body of literature indicates that growth is not limited to situations and events that have negative valence and that psychological growth may occur following any event that challenges an individual’s coping resources. A recent meta-analysis of longitudinal studies examining the effects of life events on psychological well-being reported a positive trend for self-esteem, positive relationships, and mastery following both positive and negative events, with no general evidence that negative life events had a stronger effect (33). Additionally, they found that in studies utilizing control groups, results did not significantly differ between the event and control groups, indicating that changes in outcome variables cannot necessarily be attributed to the reported life events.

Multiple conceptual models for adaptive coping with adversity and fostering resilience and growth have been proposed (e.g., PTG, coping circumplex model, systematic self-reflection, cognitive appraisal of resilience, cognitive growth, and stress) (4, 9–11, 34). All include an aspect of cognitive flexibility (e.g., cognitive processing, cognitive appraisal, rumination, problem-solving, meaning making, benefit finding, and self-reflection) as a primary mechanism for strengthening resilience after exposure to life stressors that require adaptation (i.e., psychological adjustment through the process of redefinition of the self and reappraisal of one’s beliefs). Several models include emotion regulation as the second key aspect of resilience (4, 9, 11). Recent reviews on the neurobiology of resilience converge on the central importance of the prefrontal cortex (PFC)-limbic circuitry (5–7, 35–37). Higher resilience is associated with greater emotion regulation capacity (i.e., top-down regulation of emotional responses). Greater engagement of PFC areas important for cognitive and emotional control enhances inhibition of limbic areas such as the amygdala, reducing reactivity to stressful stimuli. Resilience-related differences in resting-state EEG have also been reported. A study of children that compared groups with and without maltreatment reported greater relative left central activity (lower left compared with right alpha power) in high-resilience (composite index of adaptive functioning) individuals from both groups, whereas low resilience was associated with greater right hemisphere activity (38). A study of middle-aged adults reported that higher right frontal activity was associated with increased levels of blood biomarkers (interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and fibrinogen) indicating low-grade inflammation only in the group who reported having experienced moderate to severe abuse as children (Childhood Trauma Questionnaire) (39). As discussed by the authors, these results are consistent with higher right frontal activity indicating greater vulnerability to emotionally challenging stressors (diathesis-stress model) and that this may also increase risk for inflammation-related medical conditions.

Both cognitive and emotional approaches to coping with adversity span a wide range of strategies, some of which are detrimental to functioning. For example, rumination (repetitive thinking about an event) can be either deliberate or intrusive (40, 41). Deliberate (reflective) ruminations are adaptive, voluntary purposeful thoughts focused on better understanding of the event (i.e., its meaning, consequences, and implications). Additionally, deliberate rumination may serve as a coping strategy for managing emotional responses. Intrusive (perseverative) ruminations (e.g., worry, brooding) are maladaptive, automatic unwanted thoughts or memories that increase an individual’s distress. Intrusive rumination may also involve attempts to suppress thoughts about a stressful event. As would be expected, research indicates that intrusive and deliberate ruminations play very different roles in outcomes (41). Recent longitudinal and cross-sectional studies in a wide range of trauma-exposed groups (e.g., middle school and college students, military veterans, emergency services personnel, cancer survivors, and patients with nervous system injuries) indicate that intrusive rumination is positively associated with psychiatric symptoms, whereas deliberative rumination is positively associated with SRG (10, 42–49). As noted in several studies, these results support the potential of interventions facilitating deliberative rumination during recovery to promote better outcomes. Similarly, emotional coping may be positive and lead to emotional equilibrium (i.e., adequate emotional control), or it may be negative and result in emotional disequilibrium (e.g., emotional hyperreactivity, excessive anxiety, and suppressing emotions). These concepts are consistent with the broader body of literature that has demonstrated associations between emotion dysregulation and various forms of psychopathology (50). Studies identifying specific capacities or skills associated with higher resilience and/or better recovery from challenging events provide potential targets for interventions.

Interventions that promote cognitive flexibility and/or emotion regulation would be expected to strengthen resilience. Cognitive restructuring is one of the primary techniques utilized in cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which involves identifying and challenging negative and rigid thought patterns (51, 52). The goal is to facilitate resilience rather than to solve a particular problem or achieve a certain outcome, as illustrated in a recent study of patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) comparing CBT with eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy (53). There were no differences in clinical efficacy, but only CBT improved general life functioning (Work and Social Adjustment Scale). Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is a transdiagnostic approach that has the primary focus of fostering psychological flexibility as a pathway toward adaptation and psychological well-being (54, 55). Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of interventions that included therapeutic mindfulness (e.g., ACT, mindfulness-based stress reduction, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy) reported beneficial effects on a wide range of behavioral health outcomes (e.g., anxiety, depression, fatigue, stress, quality of life, and PTG) in adults with cancer (56, 57). Mindfulness-based interventions have also been shown to decrease use of maladaptive coping strategies (e.g., avoidance or disengagement coping, negative emotional coping) (58, 59). Dialectical-behavior therapy (DBT) may also be a useful therapeutic approach to facilitate emotion regulation, because it incorporates mindfulness, emphasizes the role of difficulties in emotion regulation, and focuses on the development of emotion-regulation skills (60–62). DBT has been shown to be effective in decreasing transdiagnostic emotion dysregulation (63–65). Overall, meta-analyses and systematic reviews of various psychosocial interventions generally show that interventions based on principles of CBT and mindfulness have the strongest effect sizes in fostering resilience and psychological growth following adverse events (66, 67). Imaging studies comparing pretreatment to posttreatment resting-state and/or task-activated functional MRI (fMRI) have reported changes in brain activation patterns following treatments that correlate with symptom improvements, suggesting beneficial neuroplastic processes (53, 68–72).

Whether self-reported growth following challenging events is primarily positive is a matter of considerable debate (34, 73–81). A key problem with research in this area is reliance on retrospective reports of self-perceived growth that may not represent genuine transformation (76, 79, 82–86). The few longitudinal studies indicate that self-perceived growth does not correlate with more objective measures of psychological growth (i.e., measures of actual psychological resources) (82, 85, 87, 88). In addition, a longitudinal study assessing veterans decades after their participation in the Yom Kippur War found that self-reported growth was linked with several detrimental outcomes, including higher rates of loneliness and lower dyadic adjustment in marital relationships (78, 80). The authors suggested that self-perceived growth may be better described as a set of defensive beliefs, a potentially maladaptive strategy for coping with distress. The Janus Face model encompasses this dichotomy by proposing that self-perceived growth following traumatic events has both a functional or constructive side and an illusory (e.g., self-deceptive or dysfunctional) side that may coexist (89, 90). The constructive side is correlated with healthy adjustment, whereas the illusory side is correlated with denial. Similarly, other studies have concluded that self-reported growth can indicate an adaptive outcome of successful cognitive coping or a positive illusion that is a result of avoidance and denial (76, 91). However, the question remains whether self-perception of growth may be beneficial to individuals even if it does not reflect measurable change. On one hand, illusory perceptions (i.e., beliefs that are not grounded in reality) are generally considered maladaptive. On the other hand, some studies have demonstrated that even perceptions of positive change may be linked with more adaptive coping (i.e., positive reinterpretation), better mental health (e.g., lower symptoms of anxiety and depression, higher stress tolerance), and increased quality of life (74, 77, 92–94). Thus, illusory or self-deceptive growth is not always associated with maladjustment. If illusory perceptions of growth coexist with and do not hinder active coping (e.g., deliberate ruminations), then they may serve as a short-term adaptive palliative coping strategy helping individuals deal effectively with the aftermath of distressing events (83, 90, 95).

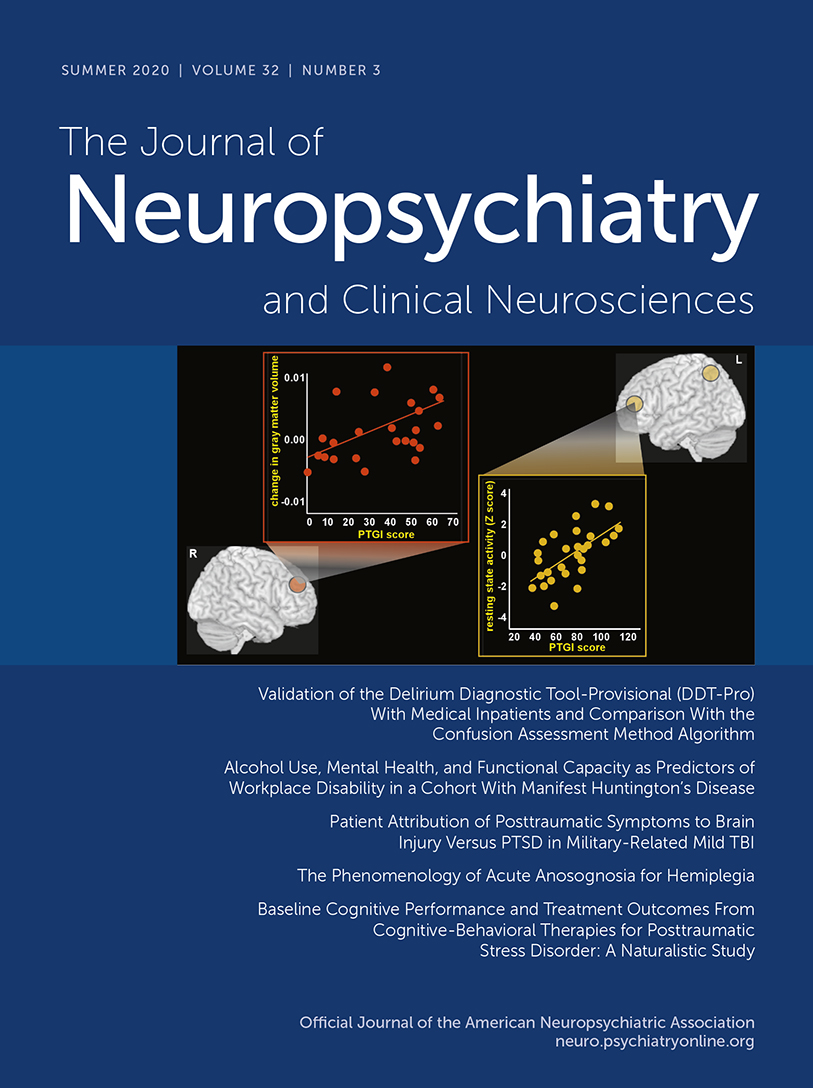

Most research on the neurobiological correlates of SRG has also utilized self-report questionnaires (e.g., the Post Traumatic Growth Index [PTGI]) that assess retrospective perception of change. Several studies have reported correlations between PTGI scores and imaging metrics within the dorsolateral PFC (Figure 2) (13–15). A study of healthy adults utilizing group spatial independent component analysis of resting-state fMRI reported a positive correlation between PTGI scores and higher resting-activity level in two left hemisphere areas that are part of the central executive network (dorsolateral PFC, superior parietal lobule) (13). A longitudinal MRI study of healthy young adults identified changes in regional gray matter volume (whole brain voxel-based morphometry) between images acquired prior to and 3 months after they experienced the East Japan Great Earthquake (14). PTGI scores were positively and significantly associated only with change in the right dorsolateral PFC (14). In the region of interest analysis, PTGI scores were positively correlated, whereas posttraumatic stress symptoms (Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale [CAPS]) were negatively correlated with changes in gray matter volume in the same area. As noted by the authors, individuals with low PTGI scores had reduced volume in this area, suggesting that the direction of volumetric changes may indicate adaptive versus maladaptive responses to stress (14). Congruent with this hypothesis, an earlier longitudinal MRI study that compared patients with PTSD and healthy individuals reported that at the earliest imaging time point (average of 1.42 years since the trauma), the PTSD group had greater cortical thickness within portions of dorsolateral PFC bilaterally (Figure 2) (15). Greater cortical thickness was positively correlated with better performance on tests of executive functioning in the PTSD group. It also correlated with greater symptom reduction (CAPS score) during the previous year and by the final time point (average of 3.85 years since the trauma). Cortical thickness had normalized by the final time point, and cortical thinning correlated with symptom resolution, indicating a role for dorsolateral PFC in supporting recovery from PTSD (15).

FIGURE 2 and COVER. Upper panel and Cover: Most research on the neurobiological correlates of stress-related growth (SRG) has utilized self-report questionnaires that assess retrospective perception of change. Two studies of healthy adults that explored relationships between Post Traumatic Growth Index (PTGI) score and imaging metrics identified the importance of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (PFC). A resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) study reported a positive correlation between PTGI scores and higher resting-activity level in two left hemisphere areas that are part of the central executive network (gold) (13). A longitudinal MRI study of individuals who experienced the East Japan Great Earthquake reported that PTGI scores were positively and significantly associated only with change in the right dorsolateral PFC volume (orange) (14). Of note, individuals with low PTGI scores had reduced volume in this area, suggesting that the direction of volumetric changes may indicate adaptive versus maladaptive responses to stress (14). Lower panel: Congruent with this hypothesis, another longitudinal MRI study that compared patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and healthy individuals reported that the PTSD group initially had greater cortical thickness within portions of the dorsolateral PFC bilaterally (yellow) (15). Initial cortical thickness correlated with greater symptom reduction at the final timepoint. By the final time point, cortical thickness had normalized, and cortical thinning correlated with symptom resolution, indicating a role for dorsolateral PFC in supporting recovery from PTSD (15).

As detailed in recent reviews, an individual’s ability to dismiss unwanted memories when they intrude into conscious awareness is an important aspect of healthy emotion regulation that may be modifiable (16, 17). This capacity is experimentally assessed by pairing items to be remembered with reminder cues and comparing results when participants are instructed to recall (Think) or instructed to not recall (NoThink) the paired items when cued. Participants also report whether a memory intrusion occurred during the NoThink condition. In healthy individuals, suppression of an intrusive memory decreases the frequency of subsequent intrusions and weakens (as indexed by decreased priming effects) the memory trace (suppression-induced forgetting, motivated forgetting, adaptive forgetting, beneficial forgetting, and selective forgetting). Recent studies of suppression-induced forgetting provide evidence that both explicit and implicit memory traces are affected (96, 97). Ability to suppress intrusions varies considerably across healthy individuals, and lower ability has been associated with higher maladaptive traits (e.g., anxiety, brooding) (17). A study of college students found that higher ability was associated with higher trauma exposure, suggesting the possibility that this capacity may be increased by successfully coping with moderate levels of adversity (16, 17). Impaired ability to suppress intrusive memories on this task has been reported for multiple psychiatric disorders, including PTSD (16, 17).

Cross-sectional fMRI studies of healthy individuals performing the Think/NoThink task have reported that memory suppression is associated with increased activation (NoThink >Think) in frontal and parietal cortices and decreased activation (NoThink <Think) in memory-related areas (e.g., hippocampus, memory-associated domain-specific cortical areas) (Figure 3) (16, 18, 19). An fMRI study that utilized unpleasant images demonstrated that an area in the right dorsolateral PFC exerted parallel top-down inhibition of the hippocampus and domain-specific areas (e.g., amygdala, sensory cortices) (18). Effective connectivity analyses indicated that intrusion of memory into awareness in the NoThink condition, which triggers increased effort to dismiss the memory, was associated with increased top-down inhibition (i.e., increased negative coupling with the right dorsolateral PFC). Greater success at suppressing intrusive memories (i.e., higher memory control) was associated with reduced intrusion frequency and reduced memory-associated negative emotion, indicating weakening of both episodic and emotional memory traces (18). An fMRI study that compared trauma-exposed individuals (in the Paris terrorist attacks) with and without PTSD to unexposed individuals on this task reported that all three groups improved on suppression with practice (fewer intrusions during NoThink trials) to a similar extent (19). However, the PTSD group differed from the trauma-exposed without PTSD and unexposed groups on functional metrics. The PTSD group had neither the robust decrease in memory strength for NoThink items (i.e., decreased priming effect indicating weakening of memory traces) nor the increase in top-down inhibition (i.e., increased negative coupling between the right dorsolateral PFC and areas important for memory such as the hippocampus) during suppression of intrusive memories seen in the other groups. As discussed by the authors, these findings indicate an impairment in memory regulation in the PTSD group that may be the reason memory intrusions are so persistent (19). Multiple authors have noted that results from this task suggest that it may be time to re-examine the common belief that all forms of memory suppression are maladaptive (16–19, 97).

FIGURE 3. An individual’s ability to dismiss unwanted memories when they intrude into conscious awareness is an important aspect of healthy emotion regulation (16, 17). This capacity is experimentally assessed by pairing items to be remembered with reminder cues and comparing results when participants are instructed to recall (Think) or instructed to not recall (NoThink) the paired items when cued. In healthy individuals, successful suppression of an intrusive memory weakens the memory trace (as indexed by decreased priming effects). Impaired ability to suppress intrusive memories on this task has been reported for multiple psychiatric disorders (16, 17). fMRI studies of healthy individuals performing the Think/NoThink task have reported that memory suppression is associated with increased activation (NoThink >Think) in frontal and parietal cortices and decreased activation (NoThink <Think) in memory-related areas (e.g., hippocampus, memory-associated domain-specific cortical areas). Approximate locations and extents of cortical activations and deactivations from two studies of healthy individuals are color-coded onto representative MRIs (18, 19). One study compared trauma-exposed individuals with and without PTSD to unexposed individuals (19). The authors reported that the PTSD group did not have the decreases in memory strength for NoThink items or the increases in top-down inhibition during suppression of intrusive memories seen in the other groups. As discussed by the authors, these findings indicate an impairment in memory regulation in the PTSD group that may be the reason memory intrusions are so persistent.

In conclusion, recent studies are contributing a new understanding of adaptive and maladaptive stress-related changes in the brain, resilience, and to the neuroplastic changes underlying SRG. This understanding offers promising evidence for recovery following even serious adversities and psychological traumas.

1 : A meta-analytic clarification of the relationship between posttraumatic growth and symptoms of posttraumatic distress disorder. J Anxiety Disord 2014; 28:223–229Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 : Strength through adversity: Moderate lifetime stress exposure is associated with psychological resilience in breast cancer survivors. Stress Health 2017; 33:549–557Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 : Neurobiology of resilience: interface between mind and body. Biol Psychiatry 2019; 86:410–420Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 : How resilience is strengthened by exposure to stressors: the systematic self-reflection model of resilience strengthening. Anxiety Stress Coping 2019; 32:1–17Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 : The biology of human resilience: opportunities for enhancing resilience across the lifespan. Biol Psychiatry 2019; 86:443–453Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 : The complex neurobiology of resilient functioning after childhood maltreatment. BMC Med 2020; 18:32Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 : Modelling resilience in adolescence and adversity: a novel framework to inform research and practice. Transl Psychiatry 2019; 9:316Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 : Resilience in cancer patients. Front Psychiatry 2019; 10:208Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 : Neurocognitive mechanism of human resilience: a conceptual framework and empirical review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16:5123Crossref, Google Scholar

10 : Rumination, event centrality, and perceived control as predictors of post-traumatic growth and distress: the Cognitive Growth and Stress model. Br J Clin Psychol 2017; 56:286–302Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 : The Coping Circumplex Model: an integrative model of the structure of coping with stress. Front Psychol 2019; 10:694Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 : The moderating effect of psychological flexibility on event centrality in determining trauma outcomes. Psychol Trauma 2020; 12:193–199Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 : Neural basis of psychological growth following adverse experiences: a resting-state functional MRI study. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0136427–e0136427Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 : Effects of post-traumatic growth on the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex after a disaster. Sci Rep 2016; 6:34364–34364Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 : The neurobiological role of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in recovery from trauma: longitudinal brain imaging study among survivors of the South Korean subway disaster. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68:701–713Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 : Memory control: a fundamental mechanism of emotion regulation. Trends Cogn Sci 2018; 22:982–995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 : Forgetting and emotion regulation in mental health, anxiety and depression. Memory 2018; 26:342–363Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 : Parallel regulation of memory and emotion supports the suppression of intrusive memories. J Neurosci 2017; 37:6423–6441Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 : Resilience after trauma: The role of memory suppression. Science 2020; 367:eaay8477Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 : Construing benefits from adversity: adaptational significance and dispositional underpinnings. J Pers 1996; 64:899–922Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 : Assessment and prediction of stress-related growth. J Pers 1996; 64:71–105Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 : The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress 1996; 9:455–471Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 : Models of life change and posttraumatic growth, in Posttraumatic Growth: Positive Changes in the Aftermath of Crisis. Edited by Tedeschi RG, Park CL, Calhoun LG. Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 1998, pp 127–151Google Scholar

24 : Positive change following trauma and adversity: a review. J Trauma Stress 2004; 17:11–21Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 : Ten surprising facts about stressful life events and disease risk. Annu Rev Psychol 2019; 70:577–597Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 : Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2014; 5:25338Crossref, Google Scholar

27 : A critical review of resilience theory and its relevance for social work. Soc Work 2018; 54:1–18Crossref, Google Scholar

28 : Resilience as a translational endpoint in the treatment of PTSD. Mol Psychiatry 2019; 24:1268–1283Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 : Resilience against traumatic stress: current developments and future directions. Front Psychiatry 2018; 9:676Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 : Resilience in clinical care: getting a grip on the recovery potential of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019; 67:2650–2657Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 : Post-traumatic growth in mental health recovery: qualitative study of narratives. BMJ Open 2019; 9:e029342Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 : Beyond recovery: exploring growth in the aftermath of psychosis. Front Psychiatry 2020; 11:108Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 : Does growth require suffering? a systematic review and meta-analysis on genuine posttraumatic and postecstatic growth. Psychol Bull 2019; 145:302–338Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 : Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol Inq 2004; 15:1–18Crossref, Google Scholar

35 : Neuroimaging correlates of resilience to traumatic events—a comprehensive review. Front Psychiatry 2018; 9:693Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36 : Resilience and the brain: a key role for regulatory circuits linked to social stress and support. Mol Psychiatry 2020; 25:379–396Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 : Neural correlates of emotion-attention interactions: From perception, learning, and memory to social cognition, individual differences, and training interventions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2020; 108:559–601Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38 : Emotion and resilience: a multilevel investigation of hemispheric electroencephalogram asymmetry and emotion regulation in maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Dev Psychopathol 2007; 19:811–840Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39 : Frontal brain asymmetry, childhood maltreatment, and low-grade inflammation at midlife. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017; 75:152–163Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40 : Assessing posttraumatic cognitive processes: the Event Related Rumination Inventory. Anxiety Stress Coping 2011; 24:137–156Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41 : Maladaptive rumination as a transdiagnostic mediator of vulnerability and outcome in psychopathology. J Clin Med 2019; 8:314Crossref, Google Scholar

42 : Women with ovarian cancer: examining the role of social support and rumination in posttraumatic growth, psychological distress, and psychological well-being. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2017; 24:47–58Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43 : Posttraumatic stress, posttraumatic growth, and satisfaction with life in military veterans. Mil Psychol 2017; 29:434–447Crossref, Google Scholar

44 : Function of personal growth initiative on posttraumatic growth, posttraumatic stress, and depression over and above adaptive and maladaptive rumination. J Clin Psychol 2017; 73:1126–1145Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45 : Predictors of post-traumatic growth in stroke survivors. Disabil Rehabil 2018; 40:2916–2924Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46 : Predicting trajectories of posttraumatic growth following acquired physical disability. Rehabil Psychol 2019; 64:37–49Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47 : Sense of coherence is linked to post-traumatic growth after critical incidents in Austrian ambulance personnel. BMC Psychiatry 2019; 19:89Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48 : Intrusive rumination, deliberate rumination, and posttraumatic growth among adolescents after a tornado: the role of social support. J Nerv Ment Dis 2019; 207:152–156Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49 : Predicting posttraumatic growth among firefighters: the role of deliberate rumination and problem-focused coping. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16:3879Crossref, Google Scholar

50 : Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic factor in the development of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology: current and future directions. Dev Psychopathol 2016; 28(4pt1):927–946Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51 : Mind Over Mood: Change How You Feel by Changing the Way You Think. New York, Guilford Publications, 2015Google Scholar

52 : Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression using mind over mood: CBT skill use and differential symptom alleviation. Behav Ther 2017; 48:29–44Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53 : Psychological and brain connectivity changes following trauma-focused CBT and EMDR treatment in single-episode PTSD patients. Front Psychol 2019; 10:129Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54 : Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies–republished article. Behav Ther 2016; 47:869–885Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55 : Acceptance and commitment therapy: a transdiagnostic behavioral intervention for mental health and medical conditions. Neurotherapeutics 2017; 14:546–553Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56 : Effects of mindfulness training on posttraumatic growth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness 2017; 8:848–858Crossref, Google Scholar

57 : The effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions among cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 2020; 28:1563–1578Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58 : Changes in disengagement coping mediate changes in affect following mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in a non-clinical sample. Br J Psychol 2016; 107:434–447Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59 : The effects of internet-delivered mindfulness training on stress, coping, and mindfulness in university students. AERA Open 2016; 2:2332858415625188Crossref, Google Scholar

60 : Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:1060–1064Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61 : Dialectical behavior therapy: current indications and unique elements. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2006; 3:62–68Medline, Google Scholar

62 : DBT Skills Training Manual. New York, Guilford Publications, 2014Google Scholar

63 : Dialectical behavior therapy skills for transdiagnostic emotion dysregulation: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 2014; 59:40–51Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64 : The therapeutic role of emotion regulation and coping strategies during a stand-alone DBT Skills training program for alcohol use disorder and concurrent substance use disorders. Addict Behav 2019; 98:106035Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65 : Dialectical behavior therapy is effective for the treatment of suicidal behavior: a meta-analysis. Behav Ther 2019; 50:60–72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

66 : Psychosocial interventions and posttraumatic growth: a meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 2015; 83:129–142Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67 : Interventions to promote resilience in cancer patients. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2019; 51-52:865–872Medline, Google Scholar

68 : Dialectical behavior therapy alters emotion regulation and amygdala activity in patients with borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Res 2014; 57:108–116Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

69 : Neurological evidence of acceptance and commitment therapy effectiveness in college-age gamblers. J Contextual Behav Sci 2016; 5:80–88Crossref, Google Scholar

70 : Neurophysiological mechanisms in acceptance and commitment therapy in opioid-addicted patients with chronic pain. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 2016; 250:12–14Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71 : Treatment for social anxiety disorder alters functional connectivity in emotion regulation neural circuitry. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 2017; 261:44–51Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

72 : The impact of mindfulness-based interventions on brain activity: a systematic review of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2018; 84:424–433Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

73 : Posttraumatic growth, posttraumatic stress and psychological adjustment in the aftermath of the 2011 Oslo bombing attack. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013; 11:160–160Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

74 : Post-traumatic growth following acquired brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol 2015; 6:1162Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

75 : Posttraumatic growth and perceived health: the role of posttraumatic stress symptoms. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2016; 86:693–703Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

76 : Posttraumatic growth in populations with posttraumatic stress disorder—a systematic review on growth-related psychological constructs and biological variables. Clin Psychol Psychother 2016; 23:469–486Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

77 : Psychological and clinical correlates of posttraumatic growth in cancer: a systematic and critical review. Psychooncology 2017; 26:2007–2018Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

78 : Posttraumatic growth and dyadic adjustment among war veterans and their wives. Front Psychol 2017; 8:1102Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

79 : Constructive, illusory, and distressed posttraumatic growth among survivors of breast cancer: a 7-year growth trajectory study. J Health Psychol (Epub ahead of print, August 6, 2018) doi: 10.1177/1359105318793199Google Scholar

80 : Growing apart: a longitudinal assessment of the relation between post-traumatic growth and loneliness among combat veterans. Front Psychol 2018; 9:893Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

81 : Posttraumatic Growth: Theory, Research, and Applications. London, Routledge, 2018Crossref, Google Scholar

82 : Post-traumatic growth: a call for less, but better, research. Eur J Pers 2014; 28:337–338Google Scholar

83 : Post‐traumatic growth as positive personality change: evidence, controversies and future directions. Eur J Pers 2014; 28:312–331Crossref, Google Scholar

84 : Perceived post-traumatic growth may not reflect actual positive change: a short-term prospective study of relationship dissolution. J Soc Pers Relat 2018; 36:3098–3116Crossref, Google Scholar

85 : Perceptions of change after a trauma and perceived posttraumatic growth: a prospective examination. Behav Sci (Basel) 2019; 9:10Crossref, Google Scholar

86 : Perceived posttraumatic growth and depreciation after spinal cord injury: actual or illusory? Health Psychol 2019; 38:53–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

87 : Does self-reported posttraumatic growth reflect genuine positive change? Psychol Sci 2009; 20:912–919Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

88 : Testing the validity of self-reported posttraumatic growth in young adult cancer survivors. Behav Sci (Basel) 2018; 8:116Crossref, Google Scholar

89 : The Janus face of self-perceived growth: toward a two-component model of posttraumatic growth. Psychol Inq 2004; 15:41–48Google Scholar

90 : Posttraumatic growth in clinical psychology: a critical review and introduction of a two component model. Clin Psychol Rev 2006; 26:626–653Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

91 : Predictors of posttraumatic growth 10-11 months after a fatal earthquake. Psychol Trauma 2018; 10:208–215Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

92 : Posttraumatic growth and adjustment among individuals with cancer or HIV/AIDS: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2010; 30:436–447Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

93 : Examining the links between perceived impact of breast cancer and psychosocial adjustment: the buffering role of posttraumatic growth. Psychooncology 2012; 21:409–418Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

94 : Posttraumatic growth, depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress symptoms, post-migration stressors and quality of life in multi-traumatized psychiatric outpatients with a refugee background in Norway. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012; 10:84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

95 : Four ways of (not) being real and whether they are essential for post-traumatic growth. Eur J Pers 2014; 28:332–361Google Scholar

96 : The impact of retrieval suppression on conceptual implicit memory. Memory 2019; 27:686–697Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

97 : Reconsidering unconscious persistence: Suppressing unwanted memories reduces their indirect expression in later thoughts. Cognition 2019; 187:78–94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar