Validation of the Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98

Abstract

The DRS-R-98, a 16-item clinician-rated scale with 13 severity items and 3 diagnostic items, was validated against the Cognitive Test for Delirium (CTD), Clinical Global Impression scale (CGI), and Delirium Rating Scale (DRS) among five diagnostic groups (N=68): delirium, dementia, depression, schizophrenia, and other. Mean and median DRS-R-98 scores significantly (P<0.001) distinguished delirium from each other group. DRS-R-98 total scores correlated highly with DRS, CTD, and CGI scores. Interrater reliability and internal consistency were very high. Cutoff scores for delirium are recommended based on ROC analyses (sensitivity and specificity ranges: total, 91%–100% and 85%–100%; severity, 86%–100% and 77%–93%, respectively, depending on the cutoffs or comparison groups chosen). The DRS-R-98 is a valid measure of delirium severity over a broad range of symptoms and is a useful diagnostic and assessment tool. The DRS-R-98 is ideal for longitudinal studies.

Research on delirium, an acute confusional state that affects on average about 20% of general hospital patients, requires the use of valid rating scales and diagnostic criteria. Beginning with the DSM-III version of the American Psychiatric Association's diagnostic manual in 1980, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria for delirium became available. These were altered in subsequent versions, DSM-III-R and DSM-IV. Although diagnostic criteria form a standard to ensure diagnosis of the delirium syndrome, they do not provide for assessment of symptom severity. Screening instruments to diagnose delirium, such as the Confusion Assessment Method1 and the Delirium Symptom Interview,2 detect some delirium symptoms but are not designed to measure symptom severity.

The Delirium Rating Scale (DRS)3 is a widely used delirium rating instrument that specifically, sensitively, and reliably measures delirium symptoms as rated by a psychiatrist or trained clinician.4,5 The DRS is available in French, Italian, Spanish, Dutch, Mandarin Chinese, Korean, Swedish, Japanese, German, and Indian-language translations.

Studies involving the DRS—reviewed elsewhere through 19985—document its strengths and limitations. Three of its items focus on features related to differential diagnosis (temporal onset of symptoms, fluctuation of symptoms, and physical etiology) and add to specificity, but are not easy to rate repeatedly during serial administrations within an episode of delirium. Some researchers have solved this problem by modifying the DRS into a 7- or 8-item scale after the initial administration. The DRS item for psychomotor behavior combines hypoactivity and hyperactivity, thereby limiting its usefulness in assessing motor subtypes of delirium. Various cognitive deficits are combined into one item because separate bedside cognitive tests were originally suggested as adjuncts to the DRS. However, not having a separate item for attentional deficits makes it difficult to study attention's presumed cardinal role in delirium or what symptoms constitute “clouding of consciousness.” The lack of items for language impairment or thought process abnormalities limits study of what actually contributes to “confusion” other than cognitive deficits. Thus, the DRS has some limitations for use in phenomenologic and longitudinal treatment research.

Our revision of the DRS was intended to address these shortcomings of the original scale. The revision includes two sections: three diagnostic items for initial ratings and a 13-item severity scale that is used for repeated measurements. Severity items were revised to emphasize gradations of symptom intensity; specific characteristics can be noted on the score sheet. Items cover language, thought processes, two motoric presentations, and five components of cognition. Neither the DRS nor its revision is intended to assess stupor or coma.

The intent of this study was to 1) validate the Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98 (DRS-R-98), 2) establish its reliability, as well as its sensitivity and specificity for distinguishing delirious from nondelirious psychiatric groups, and 3) assess its ability to function as a severity measure of delirium. It was compared with the DRS, the Cognitive Test for Delirium (CTD), and a global clinical impression scale.

METHODS

Subjects

Adult subjects were recruited from medical, surgical, psychiatric, rehabilitation, and nursing home care inpatient units of the University of Mississippi Medical Center affiliated hospitals over a 5-month period in 1999. We recruited delirious, demented, schizophrenic, depressed, and other psychiatric patients to form the five different comparison groups. Verbal assent to be interviewed was used to determine participation in this study as approved by the University of Mississippi Medical Center institutional review board. There were no exclusion criteria except an unwillingness to be psychiatrically assessed. Subjects were evaluated on the hospital unit cross-sectionally, except for a few delirious subjects who were retested after their delirium improved. Demographic data were obtained from the patient, chart, staff, and/or family and friends.

Procedures

Evaluations were done according to the availability of raters in a quasi-randomized fashion. The research team contacted the relevant service and requested a list of patients who could be approached for inclusion in the study. DRS and DRS-R-98 ratings were done blind to diagnosis by the study psychiatrists, who were trained to use these instruments. The research assistants screened cases for suitability. Ratings made use of information from all available sources, including discussions with caregivers or visitors to obtain information, as well as limited chart review under supervision of the research assistant or referring physician to maintain blindness to diagnosis. Delirium scale ratings covered a 24-hour period.

Psychiatric diagnoses were made by the referring service physician using DSM-IV criteria and all available usual clinical information to finalize the diagnosis. The referring physician also completed the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale for overall severity of illness, under instructions to compare the subjects with other patients having that same disorder. No particular training was done for completion of the CGI. CGI ratings were used to compare illness severity between groups and to correlate with delirium scale ratings within the delirium group.

Interrater reliability for the DRS-R-98 was established by using a subset of subjects representing various diagnostic groups. Research psychiatrists (P.T., D.M., R.T.) independently rated the same subjects following a single interview when they were blind to diagnosis, and comparisons were made between pairs of raters.

Construct validity was established mostly by comparing the DRS-R-98 with the DRS and to a lesser extent by comparing it with the CTD. Sensitivity and specificity of the DRS-R-98 were determined by comparing scores from delirious subjects with other diagnostic groups' scores. This comparison also assisted with evaluating criterion validity.

Scale Descriptions

The DRS is a 10-item clinician-rated scale with a maximum possible score of 32 points. Items represent symptoms that are rated on a scale of 0 to 2, 3, or 4 points, with text descriptions for each point. The items are temporal onset of symptoms, perceptual disturbances, hallucination type, delusions, psychomotor behavior, cognitive status during formal testing, physical disorder, sleep-wake cycle disturbance, lability of mood, and variability of symptoms. The DRS has good scale characteristics based on a number of studies of delirious populations. Its interrater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficients) ranges from 0.86 to 0.97 for psychiatric or geriatric physicians and 0.59 to 0.99 for nonphysicians; specificity ranges from 0.82 to 0.94, sensitivity from 0.82 to 0.94.5

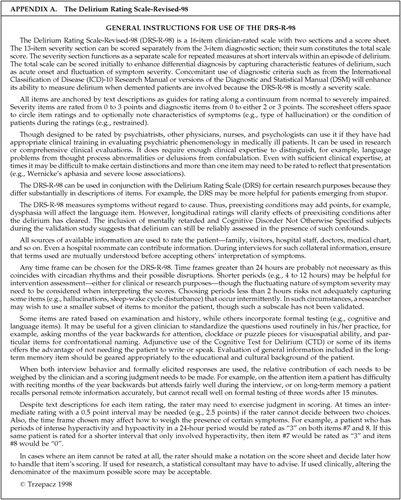

The DRS-R-98 is a 16-item scale (see Appendix A1, Appendix A2, Appendix A3, Appendix A4, Appendix A5) with a maximum total scale score of 46 points (includes the three diagnostic items) and a maximum severity score of 39 points. Whenever an item of the DRS-R-98 could not be rated—which was usually dependent on the degree of cooperation—it was so noted and later scored midway, that is, as 1.5 points; this occurred rarely. We used three words to assess short-term memory, months of the year backwards to help rate attention, copying intersecting pentagons and drawing a clockface to help assess visuoconstructional ability, and parts of a pen and/or watch to assess naming.

Each subject was administered the Cognitive Test for Delirium6 by a research assistant as a brief, broad measure of cognitive function. The CTD was designed specifically for delirious patients, especially those who cannot speak. It tests orientation, attention, visual memory, and conceptual reasoning and has been shown to correlate highly with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in delirious patients. A suggested cutoff score for delirium is ≤19 points.

The CGI is scored as a single overall impression of illness severity on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 7 points.7 It was used to grossly measure severity of illness within diagnostic groups. Unlike the other scales, the CGI was completed without prior training by a variety of treating physicians over a broad range of clinical sites.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed by using SPSS-PC software. Age and rating scale data were expressed as means and standard deviations. Statistical significance was set at P≤0.05. DRS and DRS-R-98 scores from the primary rater were used for all analyses (except in calculating interrater reliability when pairs of raters were used). Age was correlated with total rating scale scores for each diagnostic group by Pearson correlation. Chi-square was used to compare race and sex among groups.

DRS-R-98 total scores were compared with both the DRS and the CTD in delirious subjects, using a Pearson correlation to assess construct validity and ability to assess severity over a range of impairment levels. Scores for each DRS-R-98 item were correlated with DRS-R-98 total scale scores, using Cronbach's alpha coefficient to assess internal consistency of the scale as a measure of delirium. To assess empirical validity of the DRS-R-98 as a delirium scale, total and severity scores were compared among the five diagnostic groups by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with post hoc pairwise comparisons to determine where the differences lie.

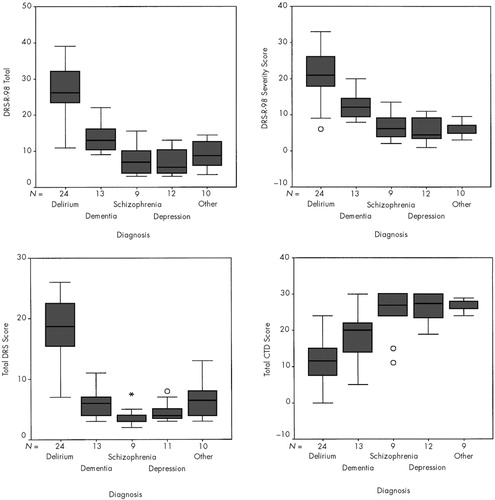

Boxplots were graphed to show medians and distributions of rating scale and CTD scores for each diagnostic group. The Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to assess for between-group difference.

DRS-R-98 scores were compared with “after usual treatment” scores by use of paired t-tests in a subset of delirious subjects to assess the DRS-R-98 as a severity scale over time. Total scores were correlated with CGI scores as another way to assess DRS-R-98 as a severity measure.

Cutoff scores for the DRS-R-98 were determined by using receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) analyses to determine acceptable levels of sensitivity and specificity when comparing the delirium group either with the demented group or with all nondelirious subjects.

CGI scores were compared between groups by using one-way ANOVA to assess whether illness severity was similar among diagnostic groups.

Interrater reliabilities for the DRS-R-98 and DRS total scores were measured by using an intraclass coefficient for pairs of independent raters.

RESULTS

Subjects

A total of 68 subjects were evaluated from five diagnostic groups: 24 delirious, 13 demented, 9 schizophrenic, 12 depressed, and 10 “other.” Twenty-seven were recruited from medical-surgical units, 17 from a medical-psychiatric unit, 15 from general psychiatric units, 4 from a nursing home unit, and 5 from a rehabilitation unit.

Table 1 describes demographic characteristics of subjects for each diagnostic group. There were no significant differences among groups for race, where 56% were white, 42% black, and 3% other (1 Hispanic and 1 Choctaw Native American). There were 51 males and 17 females (because of the inclusion of a Veterans Affairs Medical Center population) but no difference in gender or race ratios among groups. Mean age was significantly different between groups (F=7.43, df=4,63, P<0.001), as might be expected from the different age distributions of the illnesses studied. Schizophrenic subjects were significantly younger than delirious (P<0.01) or demented subjects (P<0.001), and “other” subjects were significantly younger than demented subjects (P<0.01). All groups had a broad range in age except the demented subjects, who were all over 60 years old.

Validity

Table 2 shows mean scores and standard deviations for each group for DRS, DRS-R-98 total, DRS-R-98 severity, CTD, and CGI. There was a highly significant difference among diagnostic groups for the CTD (F=19.3, df=4,62, P<0.001), DRS-R-98 total scale (F=47.9, df=4,63, P<0.001), DRS-R-98 severity scale (F=35.0, df=4,63, P<0.001) and DRS (F=44.2, df=4,62, P<0.001). The CGI also distinguished the groups (F=3.5, df=4,63, P=0.01). Delirium subjects had the highest mean scores on the delirium rating scales and the lowest scores on the CTD compared with any diagnostic group, indicating they had more delirium symptoms and cognitive impairment.

ANOVA pairwise comparisons showed that the mean DRS score was significantly higher in the delirium group compared with each of the other groups (P<0.001). The DRS did not differ among dementia, schizophrenia, depression, or “other” groups.

With pairwise comparisons, the mean DRS-R-98 total score was significantly higher in the delirium group compared with each of the other groups (P<0.001). The DRS-R-98 total score did not distinguish schizophrenia, depressed, or “other” groups from one another, nor did it distinguish dementia from the “other” group. However, it did distinguish dementia from schizophrenia and depressed groups (P<0.05).

Pairwise comparisons showed that the mean DRS-R-98 severity score was significantly higher in the delirium group compared with each of the other groups (P<0.001). It distinguished dementia from both depression and “other” groups (P<0.05), but not from schizophrenia. Like the DRS-R-98 total scale, it did not differ among “other,” schizophrenia, and depression groups.

Pairwise comparisons showed that mean CTD scores were significantly lower in the delirium group than in any other group at P<0.001, except for dementia at P<0.05. The CTD did not distinguish the schizophrenic group from any group except delirium, but it did distinguish dementia from the depressed and “other” groups (P<0.01).

Pairwise comparisons showed that mean CGI scores were not significantly different among any groups except between delirium and “other,” where the latter was less impaired than the delirium group (P=0.03). The mean CGI score was in the “moderately to markedly impaired” range for all groups except for “other” which was halfway between “mildly” and “moderately” impaired. This indicates that the major diagnostic groups were well matched for breadth of overall illness severity levels based on a clinical global impression.

In addition to comparing group means, we graphed boxplots (Figure 1) to show the distribution of scale scores in quartiles (middle 50% in the box) and median scores (in solid black lines). On Kruskal-Wallis comparisons, scores were significantly different among groups (P<0.001) for the DRS, DRS-R-98 total and severity, and CTD scales. Median scores and middle quartiles for delirious subjects did not overlap with those from any other group on any scale, except for the dementia group on the CTD, suggesting that the CTD is less discriminating. The DRS distribution shows very little overlap between delirium and any other group except between its lower quartile and the upper quartile of the dementia and “other” groups. One severely impaired schizophrenic outlier and one severely psychotically depressed outlier just reached the lowest distribution of the DRS range, as well as one “other” patient who had a recently resolved delirium.

The most overlap on boxplots for DRS-R-98 total or severity scores occurs between the lower quartile of the delirium group and the dementia group, with somewhat more overlap for the severity distribution, which includes a resolving delirium group outlier. CTD scores are lowest in the delirium group, but the boxes for delirium and dementia groups overlap, and 2 schizophrenic outliers (rated as severely and extremely severely impaired on the CGI) overlap with the delirium box.

Two subjects in the delirium group had been delirious for a while and were improving, and one subject in the “other” group had a brief nocturnal delirium that was mostly resolved by morning when he was rated. Because of their varying degrees of resolving status, these 3 subjects were analyzed separately against the other 22 subjects with delirium to see if their scores reflected their milder status. Compared with subjects having full-blown delirium, those with resolving delirium had significantly higher mean scores on the CTD (23.7±2.5 vs. 10.9±5.7; t=−3.7, df=23, P=0.001), and significantly lower on the DRS (10.3±2.3 vs. 19.3±4.8; t=3.1, df=23, P=0.005), on the DRS-R-98 total (13.0±2.0 vs. 28.2±5.4; t=4.8, df=23, P<0.001) and on the DRS-R-98 severity (7.3±1.5 vs. 22.6±4.9; t=5.3, df=23, P<0.001). There was no difference in age between those with resolving and those with more full-blown delirium.

DRS-R-98 Characteristics in Delirious Subjects

Correlations were performed between rating scales in the delirium group to address validity of the DRS-R-98. Age did not correlate with any measure. The DRS correlated strongly with the DRS-R-98 total (r=0.83, P<0.001) and DRS-R-98 severity (r=0.80, P<0.001) suggesting the newer scale is a good measure of delirium. As would be expected, the DRS-R-98 total score correlates very strongly with the DRS-R-98 severity score (r=0.99, P<0.001). Both the DRS and the DRS-R-98 correlated somewhat less strongly with the CTD (r=−0.41, P<0.05 for the DRS; r=−0.62, P=0.001 for the DRS-R-98 total; and r=−0.63, P=0.001 for DRS-R-98 severity), consistent with the delirium scales measuring symptoms more broadly than just cognition. Correlations with the CGI were strong but less so than between the two delirium rating scales with each other (r=0.45, P<0.05 for DRS; r=0.62, P=0.001 for DRS-R-98 total; and r=0.61, P=0.001 for DRS-R-98 severity), likely reflecting the CGI's more nonspecific, global nature.

DRS-R-98 Pre and Post Treatment

Six of the delirious subjects were reassessed after treatment when they no longer met DSM-IV criteria for delirium. Their mean age was 55.3±23.1 years (range 18–82). Their mean scores for CTD, DRS, DRS-R-98 severity, and CGI are listed in Table 3. There were significant improvements on all measures after treatment. In particular, the DRS-R-98 severity scale improved from a mean of 21.5±5.6 points to 5.2±3.5 (t=7.13, df=5, P<0.001), indicating an ability to measure change in clinical status in parallel to global clinical, cognitive, and diagnostic assessments. The DRS also declined from a mean score of 18.3±3.9, clearly in the delirious range, to 3.5±2.1 (t=10.6, df=5, P<0.001), clearly out of the delirious range. CGI improved significantly from “moderate/marked impairment” to “much/very much improved” (t=6.3, df=5, P=0.001). Although the delirium rating scale raters were aware of the delirium diagnosis at the second rating, the CGI was rated independently by the primary treating physician and the CTD was administered and scored by a research assistant.

Scale Reliability

The Cronbach's alpha coefficient in the delirium group was 0.90 for the DRS-R-98 total scale and 0.87 for the DRS-R-98 severity scale, supporting the reliability of the scale and its internal consistency. In addition, when the effect of each individual item was deleted from the scale, coefficients ranged from 0.88 to 0.90 for the DRS-R-98 total and from 0.84 to 0.87 for the DRS-R-98 severity scale, suggesting a high degree of internal consistency among items of the scale. Table 4 lists alpha coefficients for both the DRS-R-98 total and DRS-R-98 severity scales as each item is removed from the scale. The DRS also showed a high alpha coefficient (0.87), ranging from 0.83 to 0.87 when each item was removed, reflective of its high internal consistency.

Interrater Reliability

Three trained psychiatrist raters were used to calculate an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the DRS and DRS-R-98. When the primary rater was compared with the secondary rater for the DRS (n=25), ICC=0.99; for the DRS-R-98 total (n=26), ICC=0.98; and for the DRS-R-98 severity (n=26), ICC=0.99. When each combination of pairs of raters was compared for each rating scale, the ICCs ranged from 0.98 to 0.99 (10 or 11 cases were used for each rater pair comparison).

Sensitivity and Specificity

Results of receiver operating curve (ROC) analyses are shown in Table 5.

ROC analyses were performed for DRS-R-98 scores comparing the delirium group versus all other diagnoses, as well as the delirium group versus only dementia (dementia being the more likely diagnostic confound). When delirium was compared with all other groups for the DRS-R-98 total scale, cutoff scores of 15.25 and 17.75 were chosen as the two best options, resulting in the same sensitivity (92%), but the higher cutoff had a higher specificity (95%). The best cutoff score for the DRS-R-98 severity scale was 15.25, resulting in 92% sensitivity and 93% specificity.

The delirium group was then compared only with the dementia group, and the best cutoff scores (17.75 for total and 15.25 for severity) resulted in 92% sensitivity for both of the DRS-R-98 scales but a higher specificity for the total scale (85%) than for the severity scale (77%). On the basis of clinical experience, diagnostic items are expected to have less overlap between delirium and dementia than other symptoms.

A separate ROC analysis was performed that excluded the two resolving delirium subjects because they had significantly lower DRS-R-98 scores (see above) than other delirium subjects and would be expected to affect discrimination between groups. At the cutoff of 17.75, the DRS-R-98 total scale sensitivity increased to 100%, and higher cutoffs (21.5 and 22.5) each resulted in a somewhat lower sensitivity (91%) but increased specificities (92% and 100%, respectively). On the DRS-R-98 severity scale with a cutoff score of 15.25, excluding these two subjects resulted in an increased sensitivity of 100% with the same specificity (77%), whereas raising the cutoff score to 17 reduced the sensitivity and increased the specificity.

DISCUSSION

We describe a new delirium symptom rating scale, the DRS-R-98, that was substantially revised from the original scale, the DRS. We present data to show that this new scale functions reliably and validly both as a severity scale for repeated measurements and as a total scale that includes diagnostic items, by studying it in comparison to four other diagnostic inpatient groups whose illness severity was comparable to that of the delirium group. The DRS-R-98 is designed to measure a breadth of delirium symptoms, using phenomenological items common to psychiatric practice without making assumptions about what comprises certain domains as cited elsewhere in the literature—for example, “clouding of consciousness,” “confusion,” “incoherence,” or “psychomotor behavior.” By assessing purer symptoms individually, researchers can more accurately describe delirium, how its symptoms evolve during an episode and respond to treatment, and which symptoms might represent core symptoms or cluster into syndrome subtypes. In addition, the 13-item severity scale is more easily repeated at shorter intervals for treatment studies or to elucidate what symptom changes constitute the characteristic waxing and waning of delirium during a 24-hour period.

The DRS-R-98 appears to be a valid measure of delirium. We analyzed its characteristics for both the total scale and the severity scale. The DRS-R-98 correlated highly with scores on the DRS and the CTD in delirious subjects. Its mean and median scores were significantly higher in delirium subjects than in any of its comparison groups: dementia, depression, schizophrenia, or “other.” These patient groups were well matched for illness severity; such matching is especially important when comparing dementia and delirium groups. There was little overlap in the boxplot distribution of DRS-R-98 scores in the delirium group compared with other diagnostic groups, although the DRS-R-98 total scale had less overlap with other diagnostic groups than did the severity scale, as would be expected.

Cronbach's alpha coefficient was high (0.90), indicating high internal consistency among its 16 items; this level of consistency was largely maintained for the severity scale alone (0.87). Each item also individually contributed strongly to the scale. Interrater reliability was excellent among pairs of three psychiatrist raters doing independent ratings during a single clinical interview.

The DRS-R-98 was compared with the CTD instead of the MMSE because the CTD was designed for delirium and can be administered to nonverbal or intubated patients. Also, the CTD has the advantage of assessing some executive and more nonverbal cognitive functions of the nondominant hemisphere, which complements the verbal modalities we used during administration of the DRS-R-98. Despite this difference, the two scales correlated highly. In addition, two recent studies8,9 that relied on cognitive tests to assess delirium found high discriminating ability of the items measuring functions of the nondominant hemisphere, in keeping with the neuroanatomical hypothesis that the right-sided neural pathways, often under-studied, are integral to delirium pathophysiology.10,11

Subjects with resolving delirium were included in the delirium group for all analyses, but these subjects had less impairment on scale measurements, and their data affected the cutoff when delirium was compared with dementia. In clinical practice when such cases will be assessed, the differential from dementia will depend in part on taking a careful history. Focusing on just the DRS-R-98 diagnostic items may assist in this process. A different study using the DRS to compare delirious and delirious-demented elderly subjects found that delirium symptoms largely overshadowed dementia symptoms, although there were still some differences.4 Longitudinal testing of the DRS-R-98 in delirious-demented patients whose delirium resolves will be needed to determine which items best distinguish these groups.

In our study the CTD was less robust in distinguishing dementia from delirium, and many in our dementia group scored lower than the cutoff score of 19 points recommended in Hart and colleagues' original report.6 Our dementia group had a CTD mean score of about 18 and showed more overlap with the delirium group on boxplots than did the DRS or DRS-R-98. This is likely because the CTD measures only one dimension of delirium phenomenology, unlike these broader symptom scales.

Two delirium severity rating instruments have been published in recent years. The Confusional State Evaluation (CSE)12 is a three-part, 22-item scale from Sweden that was tested only in delirium patients (N ranged from 28 to 51 patients). Thus, no comparison was made with dementia patients, nor were sensitivity and specificity values obtainable. In addition, patients with comorbid dementia were included in the delirium group, which significantly confounds phenomenologic validity of the scale as a delirium assessment tool. Dementia patients have different symptom severity even for some overlapping symptoms.13,14 O'Keefe's Delirium Assessment Scale (DAS)15 used operationalized DSM-III criteria to compare delirious, delirious-demented, demented, and not cognitively impaired groups (N=48). Sensitivity ranged from 83% to 88% and specificity from 79% to 88% for delirium diagnosis, and interrater reliability ranged from 0.66 to 0.99. Onset of symptoms was not specifically rated, but was arbitrarily scored as acute.

Three recent delirium studies have used only cognitive tests to assess delirium.9,16,17 Hart et al.9 used a stepwise discriminant analysis of CTD item scores to determine that an abbreviated version using 2 of 9 items—visual attention span and recognition memory for pictures—discriminated 19 delirium patients in the intensive care unit from other diagnostic groups with high reliability (alpha=0.79). Bettin et al.17 found correlations of about 0.50 between cognitive tests (forward digit span and similarities) and expert serial ratings using DSM-III-R in 22 delirious and 15 control elderly subjects. These investigators felt that backward digit span had a floor effect but recommended forward digit span for monitoring symptom severity in delirium. However, O'Keefe and Grosney16 found that forward digit span did not distinguish delirium from dementia patients, suggesting that this test would be inadequate in clinical situations. Further, they found that a global rating of attentiveness, digit span backwards, and a cancellation test distinguished delirium from dementia, but that the MMSE and a vigilance test did not. However, they excluded anyone with an MMSE score ≤10, which may have biased the results away from more severe delirium cases. Also, 4 of 18 delirium subjects had comorbid dementia. Although the use of such tests is clinically expeditious, it is unlikely that cognitive tests alone can adequately capture the breadth of symptoms needed to assess delirium severity and distinguish delirium from dementia.

In summary, the DRS-R-98 is a valid and reliable symptom severity scale for delirium that has advantages over the original DRS for flexibility and breadth of symptom coverage. It is the only validated delirium rating instrument with sufficient breadth and detail for use in phenomenology and in longitudinal studies of delirium patients, including serial measurements in treatment research. Moreover, unlike most other delirium instruments, it was validated against a dementia group and other psychiatric diagnostic groups. It is currently being translated into other languages. Further research using the DRS-R-98 is needed to extend and replicate its utility, including longitudinal comparisons of conditions that can occur comorbidly with delirium.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Robert W. Baker, M.D., Andrea F. DiMartini, M.D., James Levenson, M.D., Roos van der Mast, M.D., Ph.D., and Angelos Halaris, M.D., Ph.D. for their contributions to scale development; Joel Greenhouse, Ph.D., for statistical consultation; and Henry Nasrallah, M.D., and Gurdial Sandhu, M.D., for their support during this study. This work was supported in part by the Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center, Veterans Integrated Service Network 16 (MIRECC-VISN 16), Department of Veterans Affairs.

FIGURE 1. Boxplots of DRS, DRS-R-98 Total, DRS-R-98 Severity, and CTD scores for each of the five diagnostic groupsMedian scores are denoted by the solid line within the boxes. The boxes represent the middle 50% of the scores. Outliers are denoted by open circles. DRS=Delirium Rating Scale; CTD=Cognitive Test for Delirium.

|

|

|

|

|

1 Inouye SK, van Dyke CH, Allessi CA, et al: Clarifying confusion: the Confusion Assessment Method. Ann Intern Med 1990; 113:941-948Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Albert MS, Levkoff SE, Reilly C, et al: The Delirium Symptom Interview: an interview for the detection of delirium symptoms in hospitalized patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1992; 5:14-21Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Trzepacz PT, Baker RW, Greenhouse J: A symptom rating scale for delirium. Psychiatry Res 1988; 23:89-97Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Trzepacz PT, Mulsant BH, Dew MA, et al: Is delirium different when it occurs in dementia? A study using the Delirium Rating Scale. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 10:199-204Link, Google Scholar

5 Trzepacz PT: The Delirium Rating Scale: its use in consultation-liaison research. Psychosomatics 1999; 40:193-204Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Hart RP, Levenson JL, Sessler CN, et al: Validation of a cognitive test for delirium in medical ICU patients. Psychosomatics 1996; 37:533-546Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Guy W (editor): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. (Publ No ADM 76-338). Rockville, MD, US Department of Health, Education and Welfare, 1976, pp 217-222Google Scholar

8 Mach JR Jr, Kabat V, Olson D, et al: Delirium and right hemisphere dysfunction in cognitively impaired older persons. Int Psychogeriatr 1996; 8:378-381Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Hart RP, Best AM, Sessler CN, et al: Abbreviated Cognitive Test for Delirium. J Psychosom Res 1997; 43:417-423Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Trzepacz PT: Neuropathogenesis of delirium: a need to focus our research. Psychosomatics 1994; 35:375-391Crossref, Google Scholar

11 Trzepacz PT: Is there a final common neural pathway in delirium? Focus on acetylcholine and dopamine. Seminars in Clinical Neuropsychiatry 2000; 5:132-148Medline, Google Scholar

12 Robertsson B, Karlsson I, Styrud E, et al: Confusional State Evaluation (CSE): an instrument for measuring severity of delirium in the elderly. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170:565-570Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Liptzin B, Levkoff SE, Gottlieb GL, et al: Delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1993; 5:154-160Link, Google Scholar

14 Trzepacz PT, Dew MA: Further analyses of the Delirium Rating Scale. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1995; 17:75-79Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 O'Keefe ST: Rating the severity of delirium: the Delirium Assessment Scale. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1994; 9:551-556Crossref, Google Scholar

16 O'Keefe ST, Gosney MA: Assessing attentiveness in older hospitalized patients: global assessment versus tests of attention. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997; 45:470-473Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Bettin KM, Maletta GJ, Dysken MW, et al: Measuring delirium severity in older general hospital inpatients without dementia: the Delirium Severity Scale. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1998; 6:296-307Medline, Google Scholar