A Comparison of Self-Report and Caregiver Assessment of Depression, Apathy, and Irritability in Huntington’s Disease

Abstract

The natural history of psychiatric syndromes associated with Huntington’s disease (HD) remains unclear, and longitudinal studies of symptoms such as depression, apathy, and irritability are required to better understand the progression and role of these syndromes and their effect on disability. Self-administered scales such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) may be useful to document changes in symptoms over time, but the validity of self-report may be questionable with the inevitable progression of cognitive deficits. An alternative to the patient’s self-report would be assessments by the caregiver. The authors assessed interrater agreement between patient self-assessment and caregiver assessment of patients status for the presence of depressed mood using the BDI and apathy and irritability using an apathy and irritability scale. Agreement between these scales across strata of cognitive status was also examined. Interrater agreement varied from moderate to good for the BDI, depending on patient cognitive status. Agreement for the apathy scores was low for patients with poor cognition and fair in patients with better cognition. Irritability scale agreement was fair at best and was the worst in patients with the most intact cognition. Caregiver assessment of patients’ moods and apathy may be an acceptable alternative to patient self-report as patients’ cognitive status worsens.

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a progressive neurodegenerative illness characterized by involuntary movements, cognitive impairment, and neuropsychiatric symptoms.1 It is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion2 with the genetic abnormality being an expansion of the trinucleotide repeat CAG in the HD gene.3 The pathological hallmarks of HD may predate the onset of clinical symptoms4 and consist of neuronal loss and gliosis occurring selectively in the putamen and caudate.5

Huntington’s disease is diagnosed clinically by the onset of characteristic motor abnormalities in persons at risk for developing the disease.6 However, a significant proportion of patients have cognitive and psychiatric deficits prior to the onset of motor symptoms,7,8 and there is evidence to suggest that psychiatric symptoms in HD tend to cluster in some families more than others.9 The range of neuropsychiatric syndromes seen in HD is broad and includes mood disorders, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCD), apathy, irritability, aggressive behavior as well as psychosis.2,10–12 It is unclear whether these syndromes are clinical manifestations of the pathological abnormalities underlying HD or represent a reaction to the illness itself, although the weight of the evidence would suggest the former.13–16 Research in HD has mainly focused on motor abnormalities, however, and there remain significant gaps in our understanding of the psychiatric manifestations of this disease. Although limited data exist, the natural history of these syndromes within HD remains unknown because of the cross-sectional nature of most studies looking at psychiatric symptoms. Longitudinal studies of symptoms such as depression, apathy, and irritability are needed to better understand the progression and role of these syndromes and their effect on overall disability.

Standardized self-administered scales such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)17 may be useful to document change in symptoms over time, but the validity of the BDI self-report may be questionable with the inevitable progression of cognitive deficits.18 An alternative to using a patient’s self-report would be to use assessments by the caregiver, but agreement between these separate assessments has not been examined.

We examined the interrater agreement between HD patients and their caregivers’ impressions of depressive symptoms, apathy, and irritability and rated it across different levels of cognition.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were consecutive patients with HD (N=53) and their caregivers (N=53) who accompanied them to the HD clinic at the New York State Psychiatric Institute (NYSPI), Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center, New York between 1994 and 1995. Huntington’s disease was diagnosed in each case by characteristic clinical signs and family history of illness or positive gene testing. Caregivers included patients’ spouses (N=24), parents (N=9), children (N=8), or significant others (N=12).

Procedures

Each patient was asked to complete a self-report BDI, one self-report scale assessing apathy, and one self-report assessing irritability. Using the same scales as the patients, each patient’s caregiver was asked to fill out a BDI rating the patient’s current depressive symptoms as well as the patient’s apathy and irritability.

To assess patients’ cognitive status, we administered the modified Mini Mental Status Examination (mMMSE) to measure global level of cognitive status. The mMMSE is a modification of the Folstein minimental examination.19 Scores range from a minimum of 0 points to a maximum of 57. The scale has been validated20 and used extensively to measure cognitive status in neuro-degenerative diseases.21–23

The BDI was designed in 196117 and is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 21 items with operationalized descriptions of four possible scale steps (0–3[maximum]). Comprehensive definitions of the variables are not given, and it is possible for patients to choose more than one alternative on each variable, but the highest rating is counted toward the total score. To date, four studies have used the BDI as an instrument to measure depression in HD.6,24–26 The BDI as a continuous variable was employed in all studies except one study conducted by Lawson et al.,24 which used a dichotomized cut off score for diagnosing depression.

In order to compare interrater agreement for the presence of depressed mood, we defined presence of the symptom as a score of 1 or more on the first question (Beck1) of the BDI (I am/am not depressed). This was used as a dichotomous variable for our analyses.

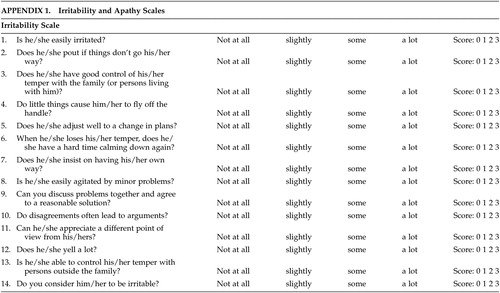

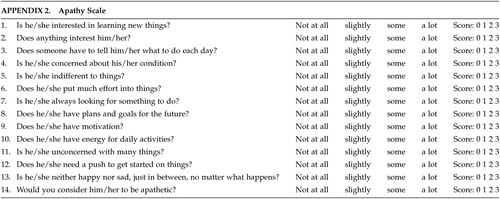

Although scales for assessing apathy and irritability exist in the literature,27–29 there remains some discussion as to the ideal scale(s) in patients with HD. The scales used in this study were designed at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and attempt to form a composite picture of an apathetic or irritability syndrome in our patients. The apathy scale consists of 14 items regarding different dimensions of apathetic behavior (see appendix). The score for each item ranges from 0 (apathetic behavior not present) to 3 (maximum intensity of apathetic behavior). The range of all possible scores is from 0–42 (maximum). The irritability scale also consists of 14 items regarding various dimensions of irritable behavior (see appendix). The score for each item ranges from 0 (irritable behavior not present) to 3 (maximum intensity of irritable behavior). The range of all possible scores is from 0 – 42 (maximum).

To our knowledge, no literature is available regarding parameters to diagnose syndromic apathy or irritability. In order to assess interrater agreement for the presence of apathy and irritability, we dichotomized the presence/absence of the syndromes by dividing the patient sample based on median scores on both scales using scores above the median as evidence of presence of apathy/irritability. Since the scale scores were normally distributed, using the median as cutoff should be valid.

To further examine whether the interrater agreement for each of these scales differed based on patients’ cognitive status, the range of all mMMSE scores (also distributed in a normal fashion) was divided into tertiles, and interrater agreement was calculated within each tertile.

Statistical Analyses

Paired t tests were used to compare mean scale scores for the BDI, apathy, and irritability scales. Interrater agreement on these scales was assessed using the kappa statistic.

RESULTS

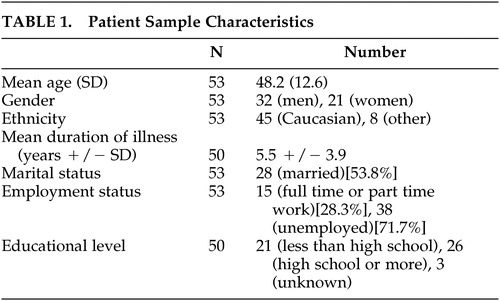

Fifty-three patients were evaluated using the three scales and the mMMSE. Demographic data on these patients are presented in Table 1.

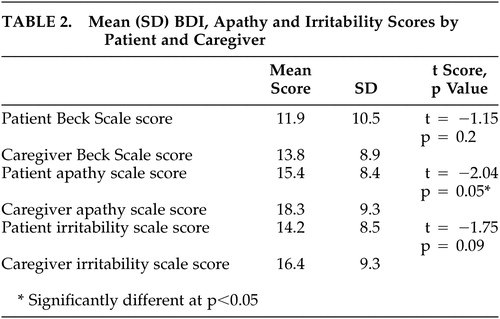

Mean total BDI scale scores rated by the patients (pbeck) and by the caregivers (cbeck) were not different from each other (Table 2). Mean total irritability scale scores rated by patients (pirrit) and those rated by caregivers (cirrit) were also similar, but mean total apathy scale scores rated by patients (papathy) and by caregivers (capathy) were different (Table 2).

Interrater reliability between patient and caregiver assessment of depressed mood was measured within each tertile of the mMMSE and was moderate to high throughout, being higher in patients within higher mMMSE tertiles (mMMSE score 0–38 [κ = 0.36], mMMSE score 39–48 [κ = 0.51], mMMSE score 49–57 [κ = 0.61]). Interrater agreement for the presence of apathy (using total apathy scale scores above median scores [papathy score >15, capathy score >19] as being apathetic) ranged from poor for the lowest mMMSE tertile (κ = 0.11), moderate for the middle tertile (κ = 0.24), and good for the highest tertile (κ = 0.57). Agreement between patients and caregivers regarding the presence of irritability (using total irritability scores above median score as being irritable (pirritability score >15, cirritability score >16) was moderate for the lowest (κ = 0.37) and middle (κ = 0.24) tertile and poor for the highest tertile (κ = 0.03).

CONCLUSIONS

The BDI is a commonly employed tool for assessing depression that has been extensively validated in various studies30,31 and has been compared with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) and the Montgomery-Asburg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), both expert-administered scales. In identifying depression, the BDI has been reported to have discriminative validity.32 Our study suggests that there is fair to good interrater agreement in terms of presence of depressed mood between patients and caregivers, and this agreement is best for patients with the most intact cognition.

Findings also indicate that interrater agreement for apathy varies, depending on cognitive status, and is poorer in the patients with worse cognition. Caregivers may be better at rating apathy than patients,27 so as cognitions worsen, caregiver estimation may be more accurate than patient assessment. The assessment of irritability by patient and caregiver was in fair agreement at best, regardless of cognitive status, and worse in patients with the most intact cognition. The reason(s) for this are not entirely clear and may reflect lack of insight into this behavior by patients.

In longitudinal studies assessing depression or apathy, patient or caregiver assessment may be used over time to explore the natural history of these syndromes as well as responses to treatments.

There are important limitations to this study. The cross-sectional design limited the ability to address relationships over time between psychiatric syndromes and cognition. Additionally, we were unable to calculate sensitivity and specificity of diagnosis for each syndrome using the scales because of the absence of a gold standard. Future studies may suggest which of the assessments (patient’s versus caregivers) are more clinically relevant based on their differential relationship to outcome. Finally, our study focused on patients with HD and not on the caregivers themselves. Little is known or has been studied regarding the stresses and reactions to illness they face and the resulting psychopathology that may ensue. This would be a suitable substrate for a future study in HD.

Longitudinal studies are needed using these and other scales to investigate the role of psychopathology in HD. Comparisons may legitimately be drawn for depressive and apathetic syndromes between patient assessments made early in the disease process and caregiver assessments as cognitive decline sets in.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by NS07153-19 (W.A. Hauser; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

|

|

|

|

1 Huntington G: On Chorea. Advances in Neurology. 1872; 1:33–35Google Scholar

2 Folstein S: Huntington’s Disease. A Disorder of Families. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1989Google Scholar

3 A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington’s disease chromosomes. The Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group. Cell. Mar 26 1993; 72(6):971–983Google Scholar

4 Gomez-Tortosa E, MacDonald ME, Friend JC, et al: Quantitative neuropathological changes in presymptomatic Huntington’s disease. Ann Neurol Jan 2001; 49:29–34Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Vonsattel JP, DiFiglia M: Huntington disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol May 1998; 57:369–384Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Nehl C, Ready RE, Hamilton J, Paulsen JS: Effects of depression on working memory in presymptomatic Huntington’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci Summer 2001; 13:342–346Link, Google Scholar

7 Diamond R, White RF, Myers RH, et al: Evidence of presymptomatic cognitive decline in Huntington’s disease. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol Nov 1992; 14:961–975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Dewhurst K, Oliver JE, McKnight AL: Socio-psychiatric consequences of Huntington’s disease. Br J Psychiatry Mar 1970; 116:255–258Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Folstein M, McHugh PR. The neuropsychiatry of some specific brain disorders. In: Lader M, Ed. Mental disorders and somatic illness. Handbook of Psychiatry. Vol 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1983:107–118Google Scholar

10 De Marchi N, Mennella R: Huntington’s disease and its association with psychopathology. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2000; 7:278–289Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Craufurd D, Thompson JC, Snowden JS: Behavioral changes in Huntington disease. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 2001; 14:219–226Medline, Google Scholar

12 Anderson KE, Louis ED, Stern Y, Marder KS: Cognitive correlates of obsessive and compulsive symptoms in Huntington’s disease. Am J Psychiatry May 2001; 158:799–801Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Cummings JL, Benson DF: Subcortical dementia. review of an emerging concept. Arch Neurol 1984; 41:874–879Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Mayberg HS, Starkstein SE, Peyser CE, Brandt J, Dannals RF, Folstein SE: Paralimbic frontal lobe hypometabolism in depression associated with Huntington’s disease. Neurol 1992; 42:1791–1797Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Mendez MF, Adams NL, Lewandowski KS: Neurobehavioral changes associated with caudate lesions. Neurol 1989; 39:349–354Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Mendez MF: Huntington’s disease: update and review of neuropsychiatric aspects. Int J Psychiatry Med 1994; 24:189–208Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Beck A, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Wagle AC, Ho LW, Wagle SA, Berrios GE: Psychometric behaviour of BDI in alzheimer’s disease patients with depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry Jan 2000; 15:63–69Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Folstein M, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Stern Y, Sano M, Paulson J, Mayeux R. Modified Mini-Mental State Examination: validity and reliability. Neurology. 1982; 37(suppl 1):179Google Scholar

21 Stern Y, Mayeux R, Sano M, Hauser WA, Bush T: Predictors of disease course in patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. Oct 1987; 37:1649–1653Google Scholar

22 Prohovnik I, Smith G, Sackeim HA, Mayeux R, Stern Y: Gray-matter degeneration in presenile Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol Feb 1989; 25:117–124Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Jacobs D, Sano M, Marder K, et al: Age at onset of Alzheimer’s disease: relation to pattern of cognitive dysfunction and rate of decline. Neurology. Jul 1994; 44:1215–1220Google Scholar

24 Lawson K, Wiggins S, Green T, Adam S, Bloch M, Hayden MR: Adverse psychological events occurring in the first year after predictive testing for Huntington’s disease. The Canadian collaborative study predictive testing. J Med Genet Oct 1996; 33:856–862Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Jankovic J, Beach J, Ashizawa T: Emotional and functional impact of DNA testing on patients with symptoms of Huntington’s disease. J Med Genet Jul 1995; 32:516–518Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Wiggins S, Whyte P, Huggins M, et al: The psychological consequences of predictive testing for Huntington’s disease. Canadian collaborative study of predictive testing. N Engl J Med Nov 12 1992; 327:1401–1405Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Marin RS, Biedrzycki RC, Firinciogullari S: Reliability and validity of the apathy evaluation scale. Psychiatry Res Aug 1991; 38:143–162Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Burns A, Folstein S, Brandt J, Folstein M: Clinical assessment of irritability, aggression, and apathy in Huntington and Alzheimer disease. J Nerv Ment Dis 1990; 178:20–26Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J: The neuropsychiatric inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. Dec 1994; 44:2308–2314Google Scholar

30 Lambert MJ, Hatch DR, Kingston MD, Edwards BC: Zung, Beck, and Hamilton rating scales as measures of treatment outcome: A meta-analytic comparison. J Consult Clin Psychol Feb 1986; 54:54–59Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Snaith RP, Taylor CM. Rating scales for depression and anxiety: A current perspective. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1985; 19 Suppl 1:17S-20S.Google Scholar

32 Plumb MM, Holland J: Comparative studies of psychological function in patients with advanced cancer-I. self-reported depressive symptoms. Psychosom Med Jul-Aug 1977; 39:264–276Google Scholar