The Behavioral Spectrum of Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome

|

Tics can be simple or complex, are usually suggestible, and may be suppressed voluntarily. 2 Premonitory feelings—localized sensations or discomforts that precede motor and vocal/phonic tics in as much as 90% of patients—are common. 4

Coprolalia (the uttering of obscenities) is reported in approximately one-third of patients referred to specialist clinics and usually has a mean age of onset of 14 years. Importantly, its prevalence is much lower in nonselected samples. Copropraxia (the making of obscene gestures) is reported in 3% to 21% of Tourette’s syndrome patients and echophenomena (the imitation of sounds, words, or actions of others) occur in 11% to 44% of patients. Palilalia and palipraxia have also been reported in a substantial proportion of patients, along with other tic-related symptoms such as stuttering and forced touching of objects/body parts. 1 It has been observed that a younger age at onset is associated with more severe Tourette’s syndrome. 5 In addition, antisocial behavior, inappropriate sexual activity, exhibitionism, aggressive behavior, discipline problems, sleep disturbances, and self-injurious behaviors are found in a substantial percentage of Tourette’s syndrome patients. 1 , 6 Kurlan et al. 7 described a number of non-obscene socially inappropriate behaviors in Tourette’s syndrome, which can be associated with social difficulties and seem to be related to losing impulse control.

The first patient with Tourette’s syndrome to be reported in the medical literature, The Marquise de Dampierre, was described in 1825 by Itard 8 and again in 1885 (when she was still experiencing tics and cursing as a recluse in her 80s) by Georges Edouard Albert Brutus Gilles de la Tourette, who included her in a cohort of nine cases which earned him eponymous fame. 9 Based on literary documents and biographies, it has been speculated that a few prominent historical figures, including Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 10 and British lexicographer Samuel Johnson, 11 suffered from Tourette’s syndrome; we disagree with the former but agree with the latter suggestion. Despite longstanding interest following these anecdotal and early descriptions, the medical literature on Tourette’s syndrome has mushroomed only in recent years. A PubMed search in late January 2006 on the keyword “Tourette” identified 2,640 papers; of these, as many as 1,984 (75.2%) were published in the last two decades ( Figure 1 ).

Although the prevalence of Tourette’s syndrome varies widely in published reports as a consequence of selection and referral biases, converging evidence from accurate epidemiological studies suggests that Tourette’s syndrome is much more common than previously thought. 12 Significantly, no less than 10 definitive studies have demonstrated a prevalence of between 0.46% and 1.85% for children and adolescents between 5 and 18 years old, giving a ballpark figure of 1%. 13 The prevalence of Tourette’s syndrome in special educational populations is even higher. 14 , 15

The etiology of Tourette’s syndrome is much more complex than previously recognized, with strong genetic influences, repeated streptococcal infections, and pre- and perinatal difficulties also affecting the phenotype. 13 Once indicated to be inherited as a single major autosomal dominant condition, several areas of interest on many chromosomes 16 and one gene have been identified for Tourette’s syndrome, 17 but no results have been replicated to date. The basal ganglia and association cortices have consistently been implicated in the pathophysiology of Tourette’s syndrome. Nearly all functional imaging studies have demonstrated reduced activity within the basal ganglia in subjects with Tourette’s syndrome relative to comparison subjects. The blood flow and metabolism studies, along with the radioligand findings, quite strongly implicate the basal ganglia portions of the dopaminergic cortico-striato-thalamic-cortical circuits in Tourette’s syndrome pathophysiology, especially in or around the caudate nucleus portions of the ventral striatum, a key region for motor and behavioral expression. 18

In fact, only a small minority of individuals with Tourette’s syndrome in clinics have no other problems. In an elegant epidemiological study by Khalifa and von Knorring, 5 the prevalence of Tourette’s syndrome was 0.6% of children between 7 and 15 years old. One important finding in this study was that only 8% of the Tourette’s syndrome patients had no other diagnosis, while as many as 36% had three or more other diagnoses. A large clinic-based multicenter study encompassing 3,500 patients with Tourette’s syndrome worldwide demonstrated that only 12% of Tourette’s syndrome patients had no other psychopathology. 19 The most commonly reported neuropsychiatric comorbidity was attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), followed by obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and depression. Anger control problems, sleep difficulties, coprolalia, and self-injurious behaviors only reached high levels in individuals with comorbidity; males were more likely than females to have comorbid disorders. In addition, several controlled studies have indicated that individuals with Tourette’s syndrome have increased anxiety, hostility, and personality disorders. 20 Thus, both in epidemiological and clinical settings, the findings are remarkably consistent that only 8%–12% of individuals with Tourette’s syndrome have no other psychopathology.

Moreover, recent factor analytic studies have suggested that there are more than one Tourette’s syndrome phenotypes and it is not a unitary condition, as it was previously thought. 21 Quite recently, Robertson and Cavanna 22 used a hierarchical clustering model followed by a principal component factor analysis to study 85 members of multigenerational kindred, of whom 69 displayed Tourette’s syndrome-related symptoms and underwent a complete genome scan. Three significant factors resulted from this analysis, accounting for approximately 42% of the symptomatic variance: factor 1 (predominantly pure tics); factor 2 (predominantly ADHD and aggressive behaviors); and factor 3 (predominantly affective-anxiety-obsessional symptoms and self-injurious behaviors). Interestingly enough, these findings replicated three of the four factors yielded by a previous factor analysis on tic symptomatology: 21 factor 1 (aggressive phenomena and self-injurious behaviors); factor 2 (purely motor and vocal tic symptoms); and factor 3 (compulsive phenomena including forced touching of objects/body parts).

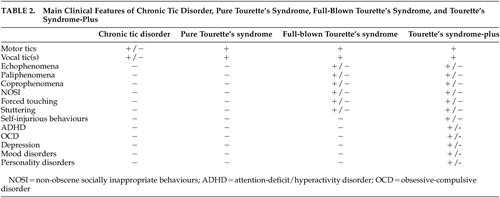

DSM-IV-TR distinguishes Tourette’s syndrome from chronic tic disorders, in which patients have either multiple motor or vocal tics, but not both. Moreover, it has been suggested 1 , 23 that it may be useful to clinically subdivide Tourette’s syndrome into “pure Tourette’s syndrome,” consisting primarily and almost solely of motor and phonic tics; “full-blown Tourette’s syndrome,” which includes coprophenomena, echophenomena, and paliphenomena; and “Tourette’s syndrome-plus” (originally coined by Packer 24 ), in which an individual can also have ADHD, significant obsessive-compulsive symptoms or OCD, or self-injurious behaviors. Others presenting with severe comorbid neuropsychiatric conditions (e.g., depression, anxiety, personality disorders and other difficult and antisocial behaviors) may also be included in this group ( Table 2 ).

|

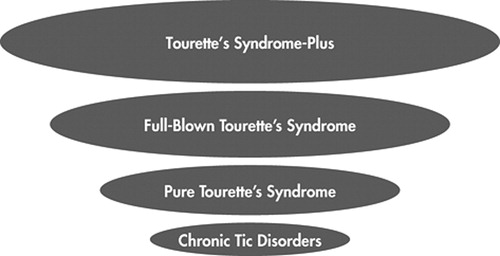

The complex pattern of the Tourette’s syndrome “core” and “peripheral” symptoms, along with the associated neuropsychiatric disorders (“Tourette’s syndrome-plus”), is graphically represented in Figure 2 .

The dimension of each area corresponds to the complexity of the clinical picture

Neuropsychiatric Comorbidities

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Currently recognized as one of the most common psychiatric disorders affecting children, ADHD has prevalence estimates ranging from 2% to 12% (around 5% in Europe and 7% in North America). 25 It has been pointed out that of all the comorbid conditions, ADHD is the most commonly encountered in Tourette’s syndrome, as evidenced by a vast literature on the subject. 26 – 28 As ADHD begins in early childhood, parents are often the first to note clumsiness, excessive activity, low frustration tolerance, and proneness to accidents. 26 Attentional problems and difficulties with hyperactivity and impulse control frequently precede the emergence of the actual tics. 29 In general, it is important that a thorough assessment is conducted to ensure that the child has both Tourette’s syndrome and ADHD. Some children with Tourette’s syndrome are so fidgety with their tics while trying to suppress them that they may appear to have poor concentration. It has also been pointed out that in children with Tourette’s syndrome it is often the symptoms of ADHD which contribute to the behavioral disturbances, poor school performance, and impaired testing of executive functioning. 29 Robertson 28 recently reviewed the relationships between Tourette’s syndrome and ADHD particularly with regard to treatment 30 and suggested that when a patient has Tourette’s syndrome and ADHD, the clinician should first assess which symptoms are the most problematic and attempt to treat those.

Tourette’s syndrome and ADHD present with a high rate of comorbidity; as many as 60%–80% of individuals with Tourette’s syndrome have comorbid ADHD, 5 , 31 and the clinical spectrum of the two neurodevelopmental disorders tends to overlap. These data are suggestive of a shared, yet unknown, neurobiological basis. The precise relationship between ADHD and Tourette’s syndrome is complex and has stimulated debate for a long time. Whether tic disorders plus ADHD reflect a separate entity and not merely two coexisting disorders, as suggested by Gillberg and colleagues, 32 is still controversial. There have been both suggestions 33 and refutations 34 that the two disorders are genetically related. It has been shown that there may be two types of Tourette’s syndrome with ADHD: those in whom ADHD is independent of Tourette’s syndrome and those in whom ADHD is secondary to Tourette’s syndrome. Another possibility is that “pure” ADHD and Tourette’s syndrome together with ADHD are phenomenologically different, but the exact relationship is unclear. These possibilities may well be related in some way 28 and more research needs to be undertaken.

The specific question as to whether coexisting Tourette’s syndrome and ADHD represent a combination of two independent pathologies (additive model), a separate nosologic entity manifested by both tics and ADHD (interactive model), or a phenotype subgroup of one of the two major clinical forms (phenotype model) has received increasing attention over time. The work of the Rothenberger group has examined the additive effect in detail. Their first study 35 indicated no additive effect at the psychophysiological level, while the second 36 only partially supported the additive model. The third 37 did provide evidence for additive effects at the level of motor system excitability, while their latest supported the notion that Tourette’s syndrome together with ADHD was indeed a separate nosological entity. 38 Thus, it appears that the additive model is becoming more convincing, but these results need to be replicated.

Relatively recently, some research groups have separated individuals with Tourette’s syndrome into subgroups, specifically separating those with and without ADHD, demonstrating significant differences. Thus, they have examined and compared different cohorts of children, including children with Tourette’s syndrome only, those with Tourette’s syndrome and ADHD, those with ADHD only, and unaffected comparison subjects. 39 – 42 Overall, these studies generally indicated that children with Tourette’s syndrome only did not differ from unaffected comparison subjects on many ratings, including aggression, delinquency, and/or conduct difficulties. By contrast, children with Tourette’s syndrome and ADHD scored significantly higher on the indices of disruptive behaviors than unaffected comparison subjects, and had similar scores as those with ADHD only. Studies further showed that children with Tourette’s syndrome and ADHD evidenced more internalizing behavior problems and poorer social adaptation than children with Tourette’s syndrome only or than comparison subjects. Of importance is that children with Tourette’s syndrome only were not significantly different from unaffected comparison subjects on most measures of externalizing behaviors and social adaptation, but did have more internalizing symptoms. The group with Tourette’s syndrome only obtained higher scores than comparison subjects on “delinquent behavior” in only one recent study, 43 which contrasts to previous findings. Finally, the high comorbidity between Tourette’s syndrome and ADHD is not limited to clinical settings. In a large study in which the subjects were from the Israeli Defense Force, 8.3% of those identified with Tourette’s syndrome had ADHD, while the ADHD population point prevalence at the time was 3.9%, which was significantly different. 44

In summary, ADHD symptoms are common in people with Tourette’s syndrome and it appears that they may occur in even mild Tourette’s syndrome cases that are identified in epidemiological studies. Moreover, individuals with Tourette’s syndrome only appear to be different from those with Tourette’s syndrome and ADHD, and this clearly has major implications in management and prognosis.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterized by persistent obsessions (recurrent, intrusive, senseless thoughts which are internally uncomfortable) or compulsions (repetitive and seemingly purposeful behaviors which are performed according to certain rules or in a stereotyped fashion); both represent a significant source of distress to the individual or interfere with social or role functioning. The lifetime prevalence rate of OCD in the general population is between 1.9% and 3.2%. 45 The modern literature indicates that OCD and Tourette’s syndrome are intimately related, although the percentage of patients with Tourette’s syndrome who also show OCD varies from 11% to 80%. 1

Both OCD and Tourette’s syndrome are childhood-onset, lifelong conditions characterized by a waxing and waning course of the symptoms, which are somewhat exacerbated by anxiety and stress. Specifically, in Tourette’s syndrome the usually volitional tic tends to respond to an unpleasant, involuntary sensation in order to reduce discomfort; likewise, in OCD the usually volitional compulsion often responds to an involuntary mental process (the obsession) and reduces discomfort. Thus, it appears that OCD bears strong similarities to Tourette’s syndrome, with the suggestion that certain obsessive-compulsive symptoms or behaviors form an alternative phenotypic expression of Tourette’s syndrome. 46 , 47 A family study by Pauls et al. 48 demonstrated that the frequency of OCD without tics among first degree relatives was significantly elevated in families of both patients with Tourette’s syndrome and OCD and in Tourette’s syndrome-OCD probands; these rates were higher than estimates of the general population and a comparison sample of adoptive relatives. Studies examining the relationship between age of onset of OCD in probands and their affected relatives have found that childhood-onset OCD is a highly familial disorder and that these early-onset cases may represent a valid subgroup, with higher genetic loading and shared vulnerability with chronic tic disorders. 49

Several studies have documented that although the obsessive-compulsive behaviors encountered in Tourette’s syndrome are integral to Tourette’s syndrome, 50 they are both clinically and statistically different from those encountered in “pure” or “primary” OCD. 51 – 58 Frankel et al. 51 reported that U.S. and U.K. patients with Tourette’s syndrome had significantly higher obsessional scores on a specially designed inventory relative to comparison subjects. The obsessional items endorsed by individuals with Tourette’s syndrome changed with increasing age, in that younger patients endorsed more items of impulse control whereas older patients endorsed items concerning checking, arranging, and fear of contamination. Cluster analysis of the inventory responses comparing OCD and Tourette’s syndrome groups revealed a group of seven questions that were preferentially endorsed by patients with Tourette’s syndrome (blurting obscenities, counting compulsions, impulses to hurt oneself), and 11 questions elicited high scores from OCD patients (ordering, arranging, routines, rituals, touching one’s body, obsessions about people hurting each other). George et al. 52 demonstrated that patients with both Tourette’s syndrome and OCD had significantly more violent, sexual, and symmetrical obsessions and more touching, blinking, counting, and self-damaging compulsions, compared with OCD-only patients who had more obsessions concerning dirt or germs and more compulsions of cleaning. The individuals who had both disorders reported that their compulsions arose spontaneously, whereas the OCD-only patients reported that their compulsions were frequently preceded by cognitions. 52 Thus, from a clinical point of view, there are differences related to family history. Other groups have found similar results in phenomenological differences between the repetitive behaviors encountered in Tourette’s syndrome and those in OCD. 55 , 56 Moreover, the patients with both Tourette’s syndrome and OCD reported that their compulsions arose spontaneously or de novo, whereas those with OCD alone reported that their compulsions were frequently preceded by cognitions. Recently, Mula et al. 58 compared the phenomenology of the obsessional thoughts between patients with Tourette’s syndrome and OCD and matched patients diagnosed with temporal lobe epilepsy and OCD. The authors found that violent and symmetrical themes were preponderant in the first group, while fear of contamination and religious/philosophical ruminations were more frequent in the second group.

Taken together, these data indicate that Tourette’s syndrome and OCD are somehow intertwined, and that specific obsessive-compulsive symptoms or obsessive-compulsive behaviors are likely to be integral to Tourette’s syndrome. 1 , 59

Depression

Depression is a common disorder, with a lifetime risk of about 10%, and rates almost double that in women. 60 It is also common in young people, occurring in about 8%, particularly in adolescent girls. Depression is sometimes referred to as a spectrum disorder, which can be mild or severe, and the lifetime suicide risk is about 15%. The etiology is often multifactorial, with a wide variety of contributory factors including genetic predisposition, and psychosocial variables such as recent adverse life events, adverse childhood circumstances (e.g., parental loss, stress, or abuse), adverse current social circumstances, and physical illness. 61 The heritability of depression has been consistently shown to be about 50%, and twin studies suggest that the familial nature of depression is entirely due to genetics and not shared environment. 62

Depression has long been found in association with Tourette’s syndrome. 63 There is now good evidence from controlled and uncontrolled studies recently reviewed by Robertson 64 to support the view that affective disorders are common in patients with Tourette’s syndrome, with a lifetime risk of 10%, and prevalence of between 1.8% and 8.9%. In specialist clinics, patients with Tourette’s syndrome, depression, or depressive symptomatology was found to occur in between 13% and 76% of 5,295 individuals. In controlled studies in clinical settings with 758 Tourette’s syndrome patients, the patients were significantly more depressed than comparison subjects in all but one instance. In community and epidemiological studies, depression in patients with Tourette’s syndrome was evident in one-fifth of the investigations. Clinical correlates of the depression in patients with Tourette’s syndrome appear to be: tic severity and duration, the presence of echophenomena and coprophenomena, premonitory sensations, sleep disturbances, OCD, self-injurious behavior, aggression, childhood conduct disorder, and possibly ADHD. 28 Depression in individuals with Tourette’s syndrome has been shown to result in a reduced quality of life, 65 and it may lead to hospitalization and even suicide in a few people. 64 Taken together, the literature indicates that depressive symptoms, and even major depressive disorder, are common in Tourette’s syndrome. In contrast, there is no evidence to suggest that the reverse is true (i.e., that Tourette’s syndrome is more common in patients with a main diagnosis of major depressive disorder). 66 In our opinion, depression is unlikely to be linked to Tourette’s syndrome per se, as is the case for comorbid OCD and possibly ADHD.

What exactly are the contributory factors of the depression in patients with Tourette’s syndrome? Tourette’s syndrome can be a distressing condition, particularly if tics are moderate to severe. Thus, depression in Tourette’s syndrome patients could be explained, at least in part, by the fact that sufferers have a chronic, socially disabling, and stigmatizing disease. Moreover, it has been clearly demonstrated that children who have been bullied at school may also become depressed 67 , 68 and some children with Tourette’s syndrome are bullied, teased, and given pejorative nicknames, and thus the depression may result from that. 1 , 64 Comorbidity with OCD is high in patients with Tourette’s syndrome, and the most common complication of OCD, ranging from 13%–75%, is depression. 69 In a large collaborative study, major depressive disorder was the most common comorbid disorder in OCD patients, occurring in 38% of subjects. 70 Next, ADHD is common in Tourette’s syndrome and ADHD has been shown to have a high comorbidity with depression; 71 thus many Tourette’s syndrome patients could be depressed because of the comorbidity with ADHD. 72 The depression in clinic Tourette’s syndrome patients may also be due to the side effects of antidopaminergic agents (both typical and atypical antipsychotics), as well as due to other medications commonly used in Tourette’s syndrome. Depression has been reported with, for example, haloperidol, pimozide, fluphenazine, tiapride, sulpiride and risperidone, as well as tetrabenazine, the calcium antagonist flunarizine, mecamylamine, and clonidine. 1 Finally, the high levels of depression in some of these studies may reflect the fact that patients who attend specialist clinics (including patients with Tourette’s syndrome) often have more than one disorder; this may introduce ascertainment bias. This view would be supported by some of the epidemiological studies, in which individuals with Tourette’s syndrome were not rated as having depressed mood relative to individuals without Tourette’s syndrome or to comparison subjects. For instance, the study by Sukhodolsky et al. 42 demonstrated that the “pure” Tourette’s syndrome subjects (i.e., those without comorbidity) were not more depressed than the comparison subjects.

In summary, the etiology of depression in Tourette’s syndrome is highly likely multifactorial, as in primary depressive illness, and less likely to be caused by a single etiological factor. The precise phenomenology and natural history of depression in the context of Tourette’s syndrome deserves more research, as well as its contribution to the Tourette’s syndrome phenotype(s). Similar to OCD, the phenomenology of depressive symptoms may differ between patients with Tourette’s syndrome and those with major depressive disorder. In depressed Tourette’s syndrome patients, new research may help address factors of particular relevance to the etiology of their depression and thus improve not only its recognition, but also treatment and outcome.

There have been suggestions 73 , 74 that bipolar disorder and Tourette’s syndrome could be related. Interestingly, it has been pointed out that Tourette’s syndrome-plus patients with comorbid bipolar disorder present with peculiar features and are particularly difficult to manage, since treating OCD with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors can precipitate mania, and atypical antipsychotics like risperidone and/or cognitive behavior therapy often fail to improve symptoms. However, numbers are small and it is likely that the relationship is with other comorbid conditions rather than with Tourette’s syndrome. Finally, with regard to psychotic disorders, in particular schizophrenia, it is generally accepted that there is no association between psychosis and Tourette’s syndrome apart from a few isolated case reports. 75 , 76

Personality Disorders

Personality disorders represent an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture. This pattern is manifested in two (or more) of the following areas: cognition, emotion, and interpersonal functioning. Moreover, the enduring pattern is inflexible and pervasive across a broad range of personal and social situations. To the best of our knowledge, there have been only three documentations of personality disorder in patients with Tourette’s syndrome. In the first study, Shapiro et al. 77 examined 36 patients with Tourette’s syndrome. No standardized interviews were utilized, but the authors were experienced psychiatrists familiar with Tourette’s syndrome. Out of the 36 patients, 27 were diagnosed as having a personality disorder (two hysterical, three inadequate, four schizoid, six passive-aggressive, one obsessive-compulsive, 11 other). Robertson et al. 78 used standardized interviews and measures to examine 39 adults with moderately severe Tourette’s syndrome (79% men) and 34 age- and sex-matched healthy comparison subjects. The Tourette’s syndrome patients and comparison subjects were examined using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders II (SCID-II) to systematically determine axis II personality disorders. All participants also completed a self-rated scale for personality disorders (SCTPD). Results showed that, using the SCID-II, 25 out of 39 Tourette’s syndrome patients (64%) had one or more DSM-III-R personality disorder, compared with only two out of 34 comparison subjects (6%), which was highly statistically significant (χ 2 =22.7, p<0.0001). The Tourette’s syndrome patients were also more likely to have an increasing number of personality disorders (χ 2 =23.8, p=0.0006). The types of personality disorders included borderline (n=11), depressive, obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, passive aggressive (n=9 in each group), avoidant (n=8), antisocial, narcissistic (n=4 in each group), hysterical, schizoid (n=3 in each group), schizotypal, and self-defeating (n=2 in each group).

On the other hand, a recent study by Cavanna et al. 79 quantified the prevalence of schizotypal traits in Tourette’s syndrome and detailed the interrelation between schizotypy, tic-related symptoms, and comorbid psychopathology. A total of 102 patients with Tourette’s syndrome were evaluated using the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire and standardized neurological and psychiatric rating scales. Overall, 15% of the subjects were diagnosed with the schizotypal personality disorder according to the DSM-IV criteria. The strongest predictors of schizotypy were obsessional and anxiety ratings; moreover, the presence of multiple psychiatric comorbidities correlated positively with schizotypy scores. The authors concluded that schizotypal traits were relatively common in patients with Tourette’s syndrome, and reflected the presence of comorbid psychopathology related to the anxiety spectrum.

It appears that in Tourette’s syndrome clinics there are an increased number of personality disorders. The range of personality disorders is across the board, and not restricted to only obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. The cause of this increase in personality disorders in Tourette’s syndrome clinic patients may well be the result of the long-term outcome of childhood ADHD, referral bias, or because of other childhood psychopathology. Thus, it does appear that at least some clinic Tourette’s syndrome populations have personality disorders, which has both treatment and prognosis implications. 78

CONCLUSION

Originally described over a century ago, Tourette’s syndrome is now recognized as a relatively common neurodevelopmental disorder, with a privileged position at the border between neurology and psychiatry. The clinical and epidemiological studies reviewed in this article suggest that associated behavioral problems are common in individuals with Tourette’s syndrome, and it seems likely that the investigation of the neurobiological bases of Tourette’s syndrome will shed light on the common brain mechanisms underlying movement and behavior regulation.

Overall, ADHD, OCD, depression, and personality disorders are the most common neuropsychiatric conditions encountered in patients with Tourette’s syndrome. The ADHD seen in Tourette’s syndrome appears to be the same as in children who do not have tics, although ADHD in Tourette’s syndrome is influenced by distraction from the tics themselves, and by the attempts to inhibit the tics. Further clinical, genetic, and neurobiological investigations are needed in order to improve the knowledge of the complex relationship between Tourette’s syndrome and ADHD. On the other hand, it is becoming increasingly evident that there is a clear and strong association between Tourette’s syndrome and OCD, both in Tourette’s syndrome patients and in their family members, with evidence obtained from phenomenological, genetic, and epidemiological investigations. Several studies have documented that although the obsessive-compulsive symptoms encountered in Tourette’s syndrome are integral, they are significantly different from those encountered in “pure” or “primary” OCD. Moreover, people with Tourette’s syndrome are more prone to depression, and the severity of this increases with the duration of Tourette’s syndrome, possibly as a consequence of having a stigmatizing disorder. Finally, the explanation for the increased rate of personality disorders in Tourette’s syndrome in clinical samples may be the result of the long-term outcome of childhood ADHD, referral bias, or other childhood psychopathology. Our suggestions as to the relationships between Tourette’s syndrome and comorbid neuropsychiatric disorders are summarized in Table 3 .

|

Both the World Health Organization and APA criteria have dictated that Tourette’s syndrome is a unitary condition. However, recent studies using hierarchical cluster analysis 80 and principal component factor analysis 22 , 23 have demonstrated that there may be more than one Tourette’s syndrome phenotype. There are also early suggestions that at least some of the many suggested etiologies may result in different phenotypes. For example, in the Alsobrook and Pauls 21 study, three out of four factors were heritable. Recently, Martino et al. 81 showed that ABGA may be more strongly associated with Tourette’s syndrome without ADHD than with Tourette’s syndrome with ADHD. With regards to the psychopathology, Eapen et al. 82 conducted a principal component factor analysis and demonstrated two factors. Thus, both the phenotype of the “tic-part” of Tourette’s syndrome and the psychopathology of Tourette’s syndrome are not homogeneous unitary entities. It seems that there are many causes and many phenotypes within the umbrella of Tourette’s syndrome.

In conclusion, it appears that Tourette’s syndrome probably should no longer be considered merely a motor disorder, and, most importantly, that Tourette’s syndrome is no longer a unitary condition as was previously thought. Future studies will demonstrate further etiological-phenotypic relationships.

1 . Robertson MM: Tourette syndrome, associated conditions and the complexities of treatment. Brain 2000; 123:425–462Google Scholar

2 . Jankovic J. Phenomenology and classification of tics, in Neurologic Clinics. Edited by Jankovic J. Philadelphia, WH Saunders Company, 1997, pp 267–275Google Scholar

3 . Tourette Syndrome Classification Study Group: Definitions and classification of tic disorders. Arch Neurol 1993; 50:1013–1016Google Scholar

4 . Kwak C, Dat Vuong K, Jankovic J: Premonitory sensory phenomenon in Tourette’s syndrome. Mov Disord 2003; 18:1530–1533Google Scholar

5 . Khalifa N, von Knorring AL: Tourette’s syndrome and other tic disorders in a total population of children: clinical assessment and background. Acta Paediatrica 2005; 94:1608–1614Google Scholar

6 . Mathews CA, Waller J, Glidden D, et al: Self-injurious behavior in Tourette’s syndrome: correlates with impulsivity and impulse control. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004; 75:1149–1155Google Scholar

7 . Kurlan R, Daragjati C, Como P, et al: Non-obscene complex socially inappropriate behavior in Tourette’s syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996; 8:311–317Google Scholar

8 . Itard JMG: Memoire sur quelques fonctions involontaires des appareils de la locomotion de la prehension et de la voix. Archiv Gen Med 1825; 8:385–407Google Scholar

9 . Gilles de la Tourette: G Etude sur une affection nerveuse caracterisee par de l’incoordination motrice accompagnee d’echolalie et de coprolalie. Arch Neurol (Paris) 1885; 9:19–42,158–200Google Scholar

10 . Simkin B: Mozart’s scatological disorder. Br Med J 1992; 305:19–26Google Scholar

11 . Murray TJ: Dr Samuel Johnson’s movement disorder. Br Med J 1979; 1:1610–1614Google Scholar

12 . Stern JS, Burza S, Robertson MM: Gilles de la tourette’s syndrome and its impact in UK. Postgrad Med J 2005; 81:12–19Google Scholar

13 . Robertson MM. Tourette’s Syndrome, in Child Psychiatry IV. Edited by Skuse D. The Medicine Publishing Company Group, Psychiatry 2005; 4:92–97Google Scholar

14 . Eapen V, Robertson MM, Zeitlin H, et al: Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome in special education. J Neurol 1997; 244:378–382Google Scholar

15 . Kurlan R, McDermott MP, Deeley C, et al: Prevalence of tics in schoolchildren and association with placement in special education. Neurology 2001; 57:1383–1388Google Scholar

16 . Keen-Kim D, Freimer NB: Genetics and epidemiology of Tourette’s syndrome. J Child Neurol 2006; 21:665–671Google Scholar

17 . Abelson JF, Kwan KY, O’Roak BJ, et al: Sequence variants in SLITRK1 are associated with Tourette’s syndrome. Science 2005; 310:317–320 Google Scholar

18 . Frey KA, Albin RL: Neuroimaging of Tourette’s syndrome. J Child Neurol 2006; 21:672–677Google Scholar

19 . Freeman RD, Fast DK, Burd L, et al: An international perspective on Tourette’s syndrome: selected findings from 3,500 individuals in 22 countries. Dev Med Child Neurol 2000; 42:436–447Google Scholar

20 . Robertson MM, Channon S, Baker J, et al: The psychopathology of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: a controlled study. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 162:114–117Google Scholar

21 . Alsobrook JP 2, Pauls DL: A factor analysis of tic symptoms in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:291–296Google Scholar

22 . Robertson MM, Cavanna AE: The Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: a principal component factor analytic study of a large pedigree. Psychiatr Genet 2007; 17:143–152Google Scholar

23 . Robertson MM. The heterogeneous psychopathology of Tourette’s syndrome, in Mental and Behavioral Dysfunction in Movement Disorders. Edited by Bedard MA, Agid Y, Chouinard S, et al. New Jersey, Humana Press, Totowa, 2003, pp 443–466Google Scholar

24 . Packer LE: Social and educational resources for patients with Tourette’s syndrome. Neurol Clin 1997; 15:457–473Google Scholar

25 . Polanczyk G, Silva de Lima M, Lessa Horta B, et al: The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:942–948Google Scholar

26 . Towbin KE, Riddle MA: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, in Handbook of Tourette’s Syndrome and Related Tic and Behavioral Disorders. Edited by Kurlan R. New York, Marcel Dekker, 1993, pp 89–109Google Scholar

27 . Freeman RD: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in the presence of Tourette’s syndrome. Neurol Clin 1997; 15:411–420Google Scholar

28 . Robertson MM: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, tics and Tourette’s syndrome: the relationship and treatment implications. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 15:1–11Google Scholar

29 . Singer HS, Brown J, Quaskey S, et al: The treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in Tourette’s syndrome: a double-blind placebo-controlled study with clonidine and desipramine. Pediatrics 1995; 95:74–81Google Scholar

30 . Robertson MM, Eapen V: Pharmacologic controversy of CNS stimulants in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Clin Neuropharmacol 1992; 15:408–425Google Scholar

31 . Zhu Y, Leung KM, Liu PZ, et al: Comorbid behavioral problems in Tourette’s syndrome are persistently correlated with the severity of tic symptoms. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2006; 40:67–73Google Scholar

32 . Gillberg IC, Rasmussen P, Kadesjo B, et al: Co-existing disorders in ADHD-implications for diagnosis and intervention. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004; 13:80–89Google Scholar

33 . Knell ER, Comings DE: Tourette’s syndrome and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: evidence for a genetic relationship. J Clin Psychiatry 1993; 54:331–337Google Scholar

34 . Pauls DL, Cohen DJ, Kidd KK, et al: Tourette’s syndrome and neuropsychiatric disorders: is there a genetic relationship? Am J Hum Genet 1988; 43:206–217Google Scholar

35 . Yordanova J, Dumais-Huber C, Rothenberger A: Coexistence of tics and hyperactivity in children: no additive at the psychophysiological level. Int J Psychophysiol 1996; 21:121–133Google Scholar

36 . Yordanova J, Dumais-Huber C, Rothenberger A, et al: Frontocortical activity in children with comorbidity of tic disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 41:585–594Google Scholar

37 . Moll GH, Heinrich H, Trott GE, et al: Children with comorbid attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder and tic disorder: evidence for additive inhibitory deficits within the motor system. Ann Neurol 2001; 49:393–396Google Scholar

38 . Yordanova J, Heinrich H, Kolev V, et al: Increased event-related theta activity as a psychophysiological marker of comorbidity in children with tics and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders. Neuroimage 2006; 32:940–955Google Scholar

39 . Spencer T, Biederman J, Harding M, et al: Disentangling the overlap between Tourette’s disorder and ADHD. J Child Psychol Psychiatr 1998; 39:1037–1044Google Scholar

40 . Stephens RJ, Sandor P: Aggressive behavior in children with Tourette’s syndrome and comorbid attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Can J Psychiatry 1999; 44:1036–1042Google Scholar

41 . Carter AS, O’Donnell DA, Schultz RT, et al: Social and emotional adjustment in children affected with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: associations with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and family functioning. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2000; 41:215–223Google Scholar

42 . Sukhodolsky DG, Scahill L, Zhang H, et al: Disruptive behavior in children with Tourette’s syndrome: association with ADHD comorbidity, tic severity, and functional impairment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:98–105Google Scholar

43 . Rizzo R, Curatolo P, Gulisano M, et al: Disentangling the effects of Tourette’s syndrome and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder on cognitive and behavioral phenotypes. Brain Dev 2007; 29:413–420Google Scholar

44 . Apter A, Pauls DL, Bleich A, et al: An epidemiologic study of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome in Israel. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:734–738Google Scholar

45 . Dinan TG: Obsessive compulsive disorder: the paradigm shift. J Serotonin Res 1995; 1(suppl 1):19–25Google Scholar

46 . Pauls DL, Leckman J, Towbin KE, et al: A possible genetic relationship exists between Tourette’s syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 1986; 22:730–733Google Scholar

47 . Eapen V, Pauls D, Robertson M: Evidence for autosomal dominant transmission in Tourette’s syndrome. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 163:593–596Google Scholar

48 . Pauls DL, Towbin KE, Leckman JF, et al: Gilles de la Tourette syndrome and obsessive compulsive disorder: evidence supporting a genetic relationship. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:1180–1182Google Scholar

49 . Rosario-Campos MC, Leckman JF, Curi M, et al: A family study of early-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiat Genet 2005; 136:92–97Google Scholar

50 . Robertson MM, Trimble MR, Lees AJ: The psychopathology of the Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: a phenomenological analysis. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 152:383–390Google Scholar

51 . Frankel M, Cummings JL, Robertson MM, et al: Obsessions and compulsions in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Neurology 1986; 36:378–382Google Scholar

52 . George MS, Trimble MR, Ring HA, et al: Obsessions in obsessive compulsive disorder with and without Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:93–97Google Scholar

53 . Baer L: Factor analysis of symptom subtypes of obsessive compulsive disorder and their relation to personality and tic disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:S18–23Google Scholar

54 . Leckman JF, Grice DE, Barr LC, et al: Tic-related vs. non-tic-related obsessive compulsive disorder. Anxiety 1994- 1995; 1:208–215Google Scholar

55 . Miguel EC, Baer L, Coffey BJ, et al: Phenomenological differences appearing with repetitive behaviors in obsessive-compulsive disorder and Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170:140–145Google Scholar

56 . Miguel EC, Rosario-Campos MC, Prado HS, et al: Sensory phenomena in obsessive-compulsive disorder and Tourette’s disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:150–156Google Scholar

57 . Cavanna AE, Strigaro G, Martino D, et al: Compulsive behaviours in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Confinia Neuropsychiatrica 2006; 1:37–40Google Scholar

58 . Mula M, Cavanna AE, Critchley HD, et al: Phenomenology of obsessive compulsive disorder in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy and Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. J Neuropsy Clin Neurosci 2008; 20:223–226Google Scholar

59 . Hounie AG, Rosario-Campos MC, Diniz JB, et al: Obsessive-compulsive disorder in Tourette’s syndrome. Adv Neurol 2006; 99:22–38Google Scholar

60 . Katona C, Robertson MM: Psychiatry at a Glance, 3rd ed. London, Blackwell Scientific Science, 2005Google Scholar

61 . Winokur G: All roads lead to depression: clinically homogeneous, etiologically heterogeneous. J Aff Disord 1997; 45:97–108Google Scholar

62 . Kendler KS, Gatz M, Gardner CO, et al: A Swedish national twin study of lifetime major depression. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:109–114Google Scholar

63 . Montgomery MA, Clayton PJ, Friedhoff AJ: Psychiatric illness in Tourette’s syndrome patients and first-degree relatives. Adv Neurol 1982; 35:335–340Google Scholar

64 . Robertson MM: Mood disorders and Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: an update on prevalence, etiology, comorbidity, clinical associations, and implications. J Psychosom Res 2006; 61:349–358Google Scholar

65 . Elstner K, Selai CE, Trimble MR, et al: Quality of life of patients with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001; 103:52–59Google Scholar

66 . Eapen V, Laker M, Anfield A, et al: Prevalence of tics and Tourette’s syndrome in an inpatient adult psychiatry setting. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2001; 26:417–420Google Scholar

67 . Salmon G, James A, Smith DM: Bullying in schools: self reported anxiety, depression, and self esteem in secondary school children. Br Med J 1998; 317:924–925Google Scholar

68 . Bond L, Carlin JB, Thomas L, et al: Does bullying cause emotional problems? A prospective study of young teenagers. Br Med J 2001; 323:480–484Google Scholar

69 . Perugi G, Toni C, Frare F, et al: Obsessive-compulsive-bipolar comorbidity: a systematic exploration of clinical features and treatment outcome. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63:1129–1134Google Scholar

70 . Perugi G, Akiskal HS, Ramacciotti S, et al: Depressive comorbidity of panic, social phobic, and obsessive-compulsive disorders re-examined: is there a bipolar II connection? J Psychiatr Res 1999; 33:53–61Google Scholar

71 . Milberger S, Biederman J, Faraone SV, et al: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and comorbid disorders: issues of overlapping symptoms. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1793–1799Google Scholar

72 . Robertson MM: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, tics and Tourette’s syndrome: the relationship and treatment implications. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 15:1–11Google Scholar

73 . Kerbeshian J, Burd L, Klug MG: Comorbid Tourette’s disorder and bipolar disorder: an etiologic perspective. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1646–1651Google Scholar

74 . Berthier ML, Kulisevsky J, Campos VM: Bipolar disorder in adult patients with Tourette’s syndrome: a clinical study. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 43:364–370Google Scholar

75 . Burd L, Kerbeshian J: Gilles de la Tourette syndrome and bipolar disorder. Arch Neurol 1984; 41:1236Google Scholar

76 . Takeuchi K, Yamashita M, Morikiyo M, et al: Gilles de la Tourette syndrome and schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986; 174:247–248Google Scholar

77 . Shapiro AK, Shapiro ES, Bruun RD, et al: Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome. New York, Raven Press, 1978Google Scholar

78 . Robertson M, Banerjee S, Fox-Hiley PJ, et al: Personality disorder and psychopathology in Tourette’s syndrome: a controlled study. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 171:283–286Google Scholar

79 . Cavanna AE, Robertson MM, Critchley HD: Schizotypal personality traits in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Acta Neurol Scand 2007; 116:385–391Google Scholar

80 . Mathews CA, Jang KL, Herrera LD, et al: Tic symptom profiles in subjects with Tourette’s syndrome from two genetically isolated populations. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 61:292–300Google Scholar

81 . Martino D, Defazio G, Church AJ, et al: Antineuronal antibody status and phenotype analysis in Tourette’s syndrome. Mov Disord 2007; 22:1424–1429Google Scholar

82 . Eapen V, Fox-Hiley P, Banerjee S, et al: Clinical features and associated psychopathology in a Tourette’s syndrome cohort. Acta Neurol Scand 2004; 109:255–260Google Scholar