Pseudocataplexy and Transient Functional Paralysis: A Spectrum of Psychogenic Motor Disorder

|

Literature Search

We undertook a systematic literature search in the MEDLINE and Embase electronic databases to see whether a similar phenomenon has been described previously. The key words and phrases used in the search were grouped into (a) depression or affective disorders and (b) pseudocataplexy, psychogenic cataplexy, transient paralysis, or transient weakness. We searched using the second group of keywords and then a combination of the first and second. We encountered two previous reports of pseudocataplexy as defined here (episodes resembling cataplexy that are sufficiently close to give rise to a suspicion of this diagnosis which prove on further assessment to have a primarily psychological explanation). 2 , 3 The patient described in the first paper 2 presented with attacks of weakness resembling cataplexy which proved likely to be psychogenic on a background after a diagnosis of narcolepsy was supported by the results of sleep laboratory investigations. A similar case was described in the second paper. 3

CASE REPORTS

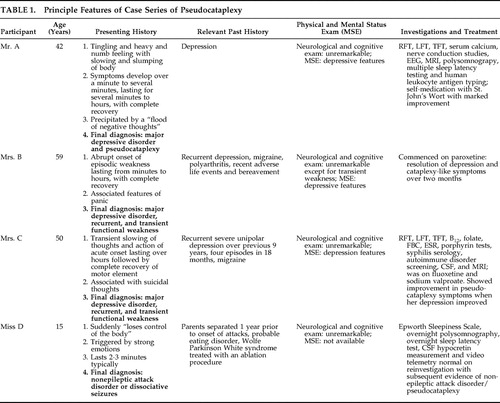

Case 1: Mr. A

A 42-year-old man reported episodes of a tingly, heavy, numb feeling spreading forward gradually from the back of his head. As it did so, his body “slowed” and slumped, so that it was difficult for him to move at all. The symptoms developed over the course of at least one minute but generally several minutes. The symptoms lasted for several minutes and sometimes for as long as an hour or two. On one occasion he thought he might have fallen asleep during an episode. He recognized that negative thoughts, sometimes triggered by arguments, often preceded the episodes. Sadness evoked by music triggered them occasionally, but laughter had not done so. Attacks sometimes coincided with a “flood of negative thoughts.” He had never felt that he was dreaming at these times. He was sometimes able to control attacks by diverting his thoughts. His Epworth Sleepiness Scale score was elevated at 15/24 (upper limit of normal 10–11), and he gave a clear history of episodes of sleep paralysis. There was a past history of depression. At a prior psychiatric interview, he became withdrawn, weak, and sleepy for up to 10 minutes when the discussion touched on negative emotions. Neurological examination was unremarkable. Mental state assessment and relevant psychiatric history enumerated signs and symptoms of depression. The initial diagnostic formulation was of narcolepsy with cataplexy with associated clinical depression. Investigations including renal and liver function, serum calcium, MRI brain scan, EEG, nerve conduction studies, polysomnograpy and multiple sleep latency testing were normal. His human leukocyte antigen (HLA) type was not typical of narcolepsy with cataplexy. The eventual DSM-IV diagnosis was major depressive disorder, single episode, mild to moderate, accompanied by episodes of “pseudocataplexy,” involving transient weakness, slowing of thought and action, and sensory disturbance associated with negative thoughts. Mr. A began to take St. John’s Wort with symptomatic improvement.

Case 2: Mrs. B

A 59-year-old woman presented with a 4-month problem of “funny turns.” These involved weakness of abrupt onset and forced her to lie down. The weakness lasted for 20 minutes to several hours, and episodes occurred once every few days. The symptoms were associated with features of panic. A typical event was witnessed (by AZ) on a visit to the clinic. Mrs. B became slow and tremulous, with lowering of her head and eyes and flexion of her right arm. She was just able to walk from the waiting room to the consulting room with support and gradually improved over a course of about 15 minutes. Psychiatric history revealed a series of stressful adverse life events including several recent bereavements. She had family duties that she found oppressive, and a lasting sense of guilt in relation to the paternity of one of her children. There was a background history of polyarthritis, recurrent depression, and migraine since her teens. She was tearful on examination. Neurological examination was normal except that her movements were generally slow and laborious and were sometimes limited by pain. A diagnosis of major depressive disorder was made using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID). We found no evidence of sleep disorder. Her depression improved markedly on treatment with paroxetine. Two months after starting treatment, Mrs. B felt less anxious and had recovered her sense of humor, and her “turns” resolved. The final diagnosis was of functional or psychogenic weakness, with features similar to those seen in case 1, secondary to major depressive episode, recurrent, in full remission.

Case 3: Mrs. C

A 50-year-old woman, with a past history of recurrent severe unipolar depression over the previous 9 years, was referred by her psychiatrist to the neurology clinic for assessment of episodes of transient severe slowing of thought and action. These were felt by her psychiatrist to be suggestive of an underlying neurological disorder. She had experienced four episodes of depression in the last 18 months, each with a characteristic onset of transitory weakness. In the most recent episode she had gone to bed after a normal day’s work and woken on the following day to find herself “unable to function.” She found herself severely slowed up and had difficulty finding and articulating words and negotiating the stairs. Her psychiatrist recalled that she had to lean against the wall to walk down a corridor while in this state. Tasks which would normally have been automatic became effortful. These episodes of weakness were transitory, lasting minutes to hours, and were highlighted by complete recovery. Soon after the onset of weakness, she developed suicidal thoughts and other features of depressive relapse. She recovered from her depression over the course of a few days, although she continued to feel “slow-witted” on occasions. She suffered from migraine. She was taking fluoxetine, 20 mg/day, sodium valproate, 400 mg b.i.d., and pindolol. There was a family history of depression and migraine in both her mother and brother. Neurological and brief cognitive examinations were unremarkable, although in a typical episode soon after her gait was slow and effortful, with slowing of fine finger movements in the right hand which lasted for the better part of an hour. Renal and liver function, calcium, thyroid function, B 12 and folate, full blood count and ESR, total porphyrin and porphyrobilinogen, syphilis serology, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear factor, CSF examination, and an MRI scan of the brain were all normal. The final diagnosis was of major depressive disorder, recurrent, mild to moderate (DSM-IV), with features of acute-onset, short-lived retardation. The features of her transient retardation were similar to, but more prolonged than, those seen in cases 1 and 2.

Case 4: Miss D

A 15-year-old schoolgirl presented with a 3-year history of episodes during which she would “lose control over her body.” Episodes were triggered by strong emotions, including laughter and anger, and were more likely to occur when she had engaged in vigorous exercise or was sleepy. The weakness, which could involve the whole body or just the head and arms, typically lasted 2–3 minutes, though occasionally longer. Although she complained of tiredness, her Epworth Sleepiness Scale score was normal at 9/21. There were no other clinical features of narcolepsy. There was a past history of Wolfe Parkinson White syndrome treated by an ablation procedure. There was concern about recent weight loss of 35 pounds over the preceding year. Her parents had separated 1 year prior to the onset of her attacks. Neurological examination was normal. Initial investigation at one sleep center suggested a diagnosis of narcolepsy, but this had been cast into doubt by normal results from overnight polysomnography, Multiple Sleep Latency Testing (MSLT), and CSF hypocretin measurement at a second center. Video-telemetry performed at a third center captured an attack regarded as typical by the patient and her mother. During the episode, she slumped onto the bed, remaining motionless for 2 minutes. During this episode, muscle tone was preserved, and the EEG revealed normal waking background rhythms. A further MSLT gave normal results. The diagnosis was of nonepileptic attack disorder or dissociative seizures.

DISCUSSION

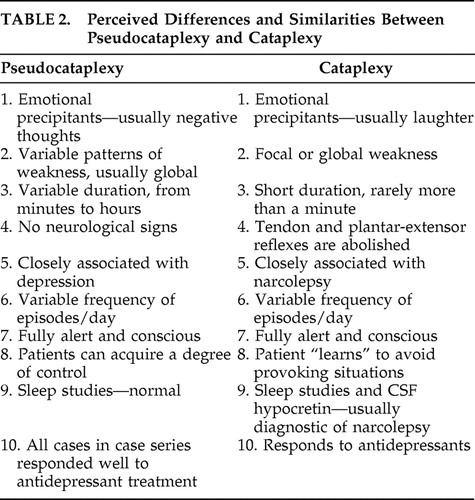

We describe a series of four patients presenting with transient weakness, lasting from minutes to hours, occurring on a background of depression in three cases and a probable eating disorder in the fourth. Neurological causes, including cataplexy in three of the four cases, were initially suspected. Further assessment, including sleep laboratory investigations in two cases, revealed no evidence for these. In the three cases with depression, successful antidepressant treatment was associated with resolution of the episodes. We adopt the term pseudocataplexy 2 , 3 to refer to this form of movement disorder, drawing attention to the potential for the misdiagnosis of these short-lived episodes of psychogenic weakness as cataplexy. Table 2 highlights the features distinguishing cataplexy and pseudocataplexy.

|

The crucial pointers to the diagnosis of pseudocataplexy in this series of patients were (a) the association of the episodes with negative thoughts rather than laughter, the typical precipitant of true cataplexy, and (b) the duration of the episodes, extending over minutes to hours rather than the seconds to a minute or so characteristic of true cataplexy. Episodes of transient weakness have a broad differential diagnosis. Transient ischemic attacks are an important differential possibility. Attacks causing widespread weakness are likely to originate from ischemia in the posterior cerebral circulation affecting the brainstem or thalamus and are often accompanied by other signs of brainstem dysfunction. They would not normally be precipitated by negative thoughts. The duration of a transient ischemic attack is variable, from seconds to hours. Presyncope can cause transient global weakness; the diagnosis is usually suggested by prodromal symptoms such as a feeling of faintness, alterations of vision and hearing, and an appropriate precipitating situation in someone who is, as a rule, standing. Transient weakness occurs in myasthenia gravis, usually in association with repeated movement, giving rise to “fatigueable weaknesses.” Transient weakness in migraine or hypoglycemia will usually be associated with other, more typical symptoms of these disorders. The transient weakness seen in the inherited ion channel disorders (“channelopathies”) giving rise to periodic paralysis is normally present for hours rather than minutes and is often provoked by exertion or eating. Epilepsy can cause transient weakness in the wake of a seizure, a “Todd’s palsy,” but if so the preceding seizure will usually be apparent. Similarly, patients with multiple sclerosis can experience transient worsening or emergence of weakness when hot, but the clinical context will usually make the explanation clear.

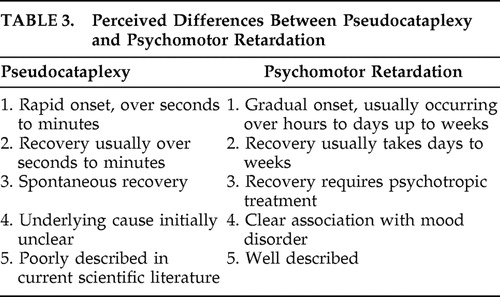

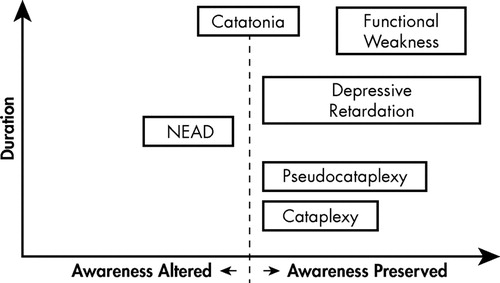

Pseudocataplexy is a form of “functional” or psychogenic movement disorder generally diagnosed in neurological contexts. Closely related presentations include nonepileptic attack disorder, and “functional weakness.” Nonepileptic attack disorder is, like pseudocataplexy, paroxysmal and short-lived but is generally associated with altered awareness and convulsive movements. 4 As seen in case 4, pseudocataplexy is characterized by weakness and apparent loss of muscle tone occurring in clear consciousness. Functional weakness is typically prolonged, lasting for weeks to years, and is generally focal rather than global, often manifesting in functional hemiparesis or paraparesis. 5 This contrasts with the examples of pseudocataplexy described here which were relatively brief and global. Like pseudocataplexy, however, nonepileptic attack disorder and functional weakness are often associated with mood disturbance. Catatonia and depressive retardation are related forms of motor disturbance typically diagnosed in psychiatric contexts. While catatonia is a complex disorder with a range of psychiatric associations, it is seen most commonly in patients with mood disorders. Both catatonia and depressive retardation are typically prolonged for days to weeks. The weakness seen in case 3 was relatively prolonged, persisting on some occasions for a number of hours, but its acute onset gave rise to suspicion of an underlying neurological cause, such as cataplexy. No neurological cause came to light, however.

The cases of pseudocataplexy described here might reasonably be regarded as episodes of “acute retardation,” given their association—most apparent in cases 1 and 3—with negative cognition. Our aim in introducing the term “pseudocataplexy” is not to deny a possible link with depressive retardation but to draw attention to the risk of mistaking acute transient weakness of psychological origin with transient weakness due to neurological disorder, in particular the transient weakness seen in cataplexy. Table 3 looks to differentiate between psychomotor retardation and pseudocataplexy. Psychomotor retardation, as classically described, involves a relatively prolonged period of hypokinesia, occurring in the context of overt mood disorder, recovering slowly with psychotropic treatment. In the case of pseudocataplexy as described here, the motor disturbance was relatively brief; mood disorder, though evident, was not initially regarded as the cause; and individual episodes resolved without treatment. It is possible that the pathophysiology of these episodes of short-lived weakness, occurring in association with depression, shares some common ground with that of true cataplexy. Figure 1 illustrates our understanding of where pseudocataplexy sits with regard to its nearest differentials with regard to consciousness and duration of episode. Cataplexy is thought to result from the intrusion of REM sleep atonia into wakefulness, and, more generally, the syndrome of narcolepsy-cataplexy is characterized by a dysregulation of REM sleep. Not only cataplexy but also sleep-onset REM periods, sleep paralysis, and hypnologic hallucinations are aberrant expressions of REM sleep. Affective disorders have been shown to alter sleep architecture, causing a shortening of REM latency and increasing REM density. 6 , 7 Thus abnormalities of REM sleep are common to narcolepsy and depression. Recent neurobiological findings suggest a further link: the syndrome of narcolepsy-cataplexy is thought to result from a specific deficiency of the hypothalamic neurotransmitter hypocretin, levels of which can also be disturbed in depression. 8 , 9 Finally, both pseudocataplexy and true cataplexy respond to antidepressant treatment.

|

NEAD = nonepileptic attack disorder

In conclusion, the transient atonia and paralysis seen in cataplexy can be mimicked by a form of transient functional or psychogenic motor disturbance usually occurring in association with mood disorder. Precipitation of the episodes by negative thoughts and low mood, and a duration greater than normally expected in true cataplexy, should raise suspicion of pseudocataplexy. Appropriate psychiatric diagnosis and management may lead to cessation of the attacks.

1. Yudofsky SC, Hales RE: The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, 5th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2008, p 696Google Scholar

2. Krahn L, Hansen M, Shepard J: Pseudocataplexy. Psychosomatics 2001; 42:356–358Google Scholar

3. Krahn LE, Lymp JF, Moore WR, et al: Characterizing the emotions that trigger cataplexy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005; 17:45–50Google Scholar

4. Francis P, Baker GA: Nonepileptic Attack Disorder (NEAD): a comprehensive review. Seizure 1999; 8:53–61Google Scholar

5. Stone J, Carson A, Sharpe M: Functional symptoms and signs in neurology: assessment and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005; 76(suppl 1):i2–12Google Scholar

6. Abad VC, Guilleminault C: Sleep and Psychiatry. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2005; 7:291–303Google Scholar

7. Pollmacher T, Mullington J, Lauer JC: REM Sleep disinhibition at sleep onset: a comparison between narcolepsy and depression. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 42:713–720Google Scholar

8. Ganjavi H, Shapiro CM: Hypocretin/Orexin: a molecular link between sleep, energy regulation, and pleasure. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2007; 19:413–419Google Scholar

9. Salomon RM, Ripley B, Kennedy JS, et al: Diurnal variation of CSF hypocretin-1 (Orexin-A) levels in control and depressed subjects. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 54:96–104Google Scholar