Interrelationships of Anger and PTSD: Contributions From Functional Neuroimaging

There is growing recognition that anger can have both negative and positive roles in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).13–17 In addition to being a potential symptom, anger has been implicated as a risk factor for developing PTSD and as contributing to poorer functional outcomes (e.g., relationships, quality of life, treatment efficacy). Trauma-related anger may also contribute to post traumatic growth. Thus, interventions targeting dysfunctional anger expression and/or management have potential to improve both mental and physical health outcomes for individuals with PTSD. These and other findings indicate the importance of understanding the neurobiology of both adaptive and maladaptive anger.

Anger can be either adaptive (e.g., positive, healthy, functional) or maladaptive (e.g., negative, unhealthy, dysfunctional).13,18–25 Anger is considered adaptive when it is elicited and expressed appropriately, maladaptive when it is elicited and/or expressed inappropriately (e.g., triggered too easily, expressed more strongly than warranted by the situation). The adaptive value of anger has been described in many ways: helping organisms respond to challenges in a more flexible way; signaling that unfairness and/or injury has occurred to promote active negotiation to achieve resolution; surmounting an obstacle to achieving a desired goal. In these examples the value of anger is to motivate expenditure of effort to remove an obstacle. Studies utilizing a variety of role-playing situations involving negotiations (landlord and tenant, terms of class project, seller and buyer) have demonstrated that moderate use of anger-conveying behaviors (e.g., confrontational tone, raising voice) facilitated gain during negotiations.26,27 In contrast, expression of no anger or intense anger were both detrimental. Another study found that individuals with higher levels of emotional intelligence were more likely to prefer the situationally useful emotion rather than a more pleasant emotion (e.g., anger rather than happiness in confrontational situations).28 Possibly related, a study that utilized daily diaries reported that individuals differed on the affective valence (negative or positive) associated with anger episodes.29 The authors of that study suggested that individual differences in the motivational direction of anger (whether it is experienced as promoting approach or avoidance) may be relevant to maladaptive anger in psychiatric disorders. Another study reported that individuals higher in trait anger (trait anger subscale from the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory [STAXI]) were biased toward approaching rather than avoiding angry faces.30 Trait anger is generally believed to be a stable dispositional characteristic of an individual, and high trait anger is thought to indicate higher likelihood of experiencing and expressing anger.31 However, studies using diary methodology in healthy individuals to capture angering events have reported that trait anger is at most modestly predictive of the day-to-day experience of anger.31,32

An aspect of the study of anger highly relevant to the results of functional imaging studies is the wide range of stimuli that have been utilized as the anger condition.19,21,22,24,33 Angry faces are the most common, either simply viewing or with an associated task. Depending on the context, a variety of internal processing might be evoked in addition to anger recognition, such as thinking about being angry, experiencing an emotional response (e.g., anger, fear, anxiety), and/or suppressing an emotional response. The diverse stimuli that have been used to induce the state of being angry and/or to elicit anger-related behavior also are likely to differ in the internal processing evoked. In the context of PTSD, the DSM-5 makes a clear distinction between feeling angry (criterion D) and anger-induced behaviors (criterion E).34

Multiple functional imaging studies using a diversity of analytic approaches have reported that different basic emotions (e.g., anger, fear, happiness) are associated with specific patterns of neural activation.1,18,24,35–39 Two meta-analyses that used activation likelihood estimation (ALE) reported relatively similar areas of convergence for anger-related stimuli.1,37 Only a few of the included functional imaging studies were of state anger, as facial expressions were the most commonly used anger stimuli. The meta-analysis that compared activations when all studies of anger were included to only studies using faces as stimuli (10/16) found that more than half of activations (8/13) were still significant (Figure 1).1 A study in healthy individuals reported increased functional connectivity (functional MRI [fMRI]) during viewing of angry faces (compared with neutral) between the amygdala and a set of region that overlapped very little with the meta-analyses (Figure 1).2 Two recent fMRI studies compared groups of males (community, military veterans) divergent on trait anger (STAXI-revised [STAXI-2]) while viewing emotional pictures.4,5 Both studies reported that high trait anger was associated with higher activations in multiple areas (Figure 2).4,5 The group that compared military veterans with and without problematic anger and aggression also assessed functional connectivity (seed-based) of the amygdala and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC).5 Although there were no task-related changes in functional connectivity using amygdala seeds, connectivity of the dACC with amygdala was higher in veterans with problematic anger during processing of negative images.

FIGURE 1. Functional imaging studies use a variety of stimuli to study anger and differ greatly in analytic approaches. Illustrated here are some representative examples overlaid on MRI. Results from both the left and right hemispheres are combined on the medial and lateral views. A meta-analysis that compared activations when all studies of anger were included (pink) with activations when angry faces were the stimuli (pink with white outline) found that more than half of the areas were still significant.1 A mostly different set of regions (green) became more functionally connected (functional MRI [fMRI]) with the amygdala during viewing of angry faces.2 The regions that predicted (pattern classification) that the subject was experiencing anger (orange) in an fMRI study that utilized emotionally evocative music and films overlap partially with results from studies that used viewing of angry faces as the stimuli.3

FIGURE 2. Two recent fMRI studies compared activations during viewing of emotional pictures between males with high trait anger and males with normal trait anger.4,5 Both studies reported that high trait anger was associated with higher activations in multiple areas. In the study utilizing community members, this effect was found only for unpleasant images.4 All areas of greater activation were on the left (blue). The study that compared military veterans with and without problematic anger and aggression reported higher activations for both positive and negative images (purple).5 Results from both the left and right hemispheres are combined on the medial and lateral views.

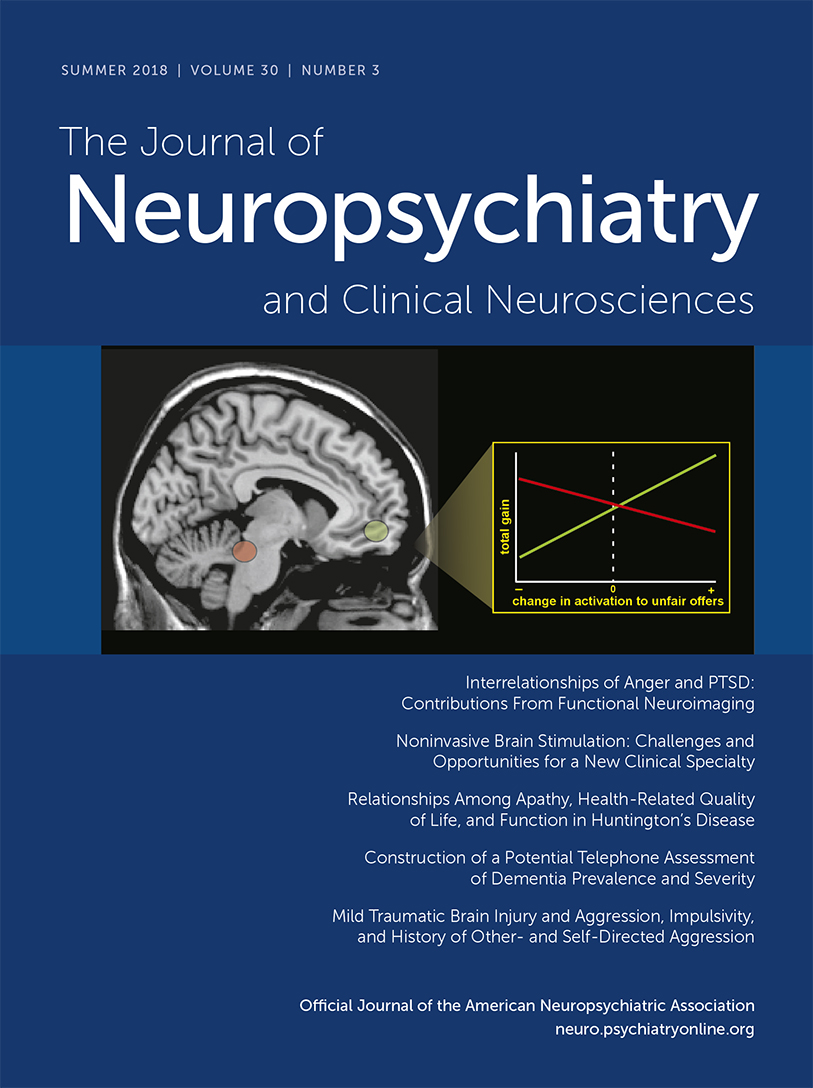

The neural activations associated with state anger have been evaluated in several fMRI studies that included some form of emotion generation or induction (e.g., imagery based on personal script, music, films, nonphysical provocation by opponent).3,10,11,40–42 Functional MRI studies that used pattern classification identified combinations of areas that predicted the emotion experienced (e.g., anger, disgust, fear, happiness) both within and across individuals at well above chance levels.3,40–42 The regions that predicted state anger were mostly different from the regions identified in the meta-analyses of functional imaging studies presented previously (Figure 1).3 A series of studies from one group used two methods of provoking state anger during fMRI (Ultimatum Game [UG] modified to have multiple negotiation rounds with an intentionally obnoxious opponent, anger-provoking films) in an effort to identify imaging biomarkers of vulnerability and/or resilience to military-training related stressors.6–9 Functional MRI studies were performed prior to training. Traumatic stress symptoms (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Check-List–Military [PCL-M]) were measured at the end of a year of intense military combat training. Level of success in playing the modified UG was measured by amount of money gained. Poorer performance on the modified UG (low gain) was associated with higher symptoms at the end of training. The high gain and low gain groups did not differ on trait anger or trait anxiety. However, the high gain group reported lower levels of anger during provocation, suggesting better self-regulation of emotion. Higher global functional connectivity of the amygdala (resting-state fMRI) prior to anger induction was negatively correlated with level of anger following provocation. Performance was positively correlated with activation within the orbitofrontal cortex and slower skin conductance response (SCR) and negatively correlated with activation in a brainstem area that includes the locus coeruleus (Cover and Figure 3).6 Locus coeruleus is one of the areas where startle-related activation is greater in subjects with PTSD.12 Greater activation within the orbitofrontal cortex was also reported in an fMRI study that used a different anger-provoking game in healthy males.10 The authors speculated that this indicated greater self-regulation of emotion. Another fMRI study in healthy individuals used personal script-evoked imagery to induce anger.11 Activation increased within the amygdala during anger induction, followed by activation within the orbitofrontal cortex during anger imagery that was negatively correlated (trend level) with self-reported anger. Greater habitual use of cognitive reappraisal for self-regulation of emotion was negatively associated with amygdala activations during viewing of negative images in trauma exposed military veterans regardless of PTSD status.43 In contrast, greater treatment-related symptom reductions in veterans with combat-related PTSD correlated with increased activations in the amygdala and several medial prefrontal cortex regions to angry (but not neutral or fearful) faces.44

COVER and FIGURE 3. Several fMRI studies have explored relationships between reactions to anger-provoking tasks and traumatic stress symptoms. In a series of studies, one group has identified neuroimaging patterns that have potential as biomarkers for vulnerability and/or resilience to stressors.6–9 Functional MRI studies were performed prior to a year of intense military combat training. Traumatic stress symptoms were measured at the end of training. The anger-provoking task was a version of the Ultimatum Game modified to have multiple negotiation rounds with an intentionally obnoxious opponent. Level of success was measured by total money gained. Poorer performance (lower gain) was associated with higher traumatic stress symptoms at the end of training. Performance was positively correlated with activation within the orbitofrontal cortex (green) and slower skin conductance response and negatively correlated with activation in a brainstem area that includes the locus coeruleus (red).6 The same general area of the orbitofrontal cortex was activated in other recent fMRI studies of state anger and anger regulation.10,11 One study utilized a different anger-provoking game (gold).10 The other used personal script-evoke imagery (blue).11 Locus coeruleus is one of the areas where startle-related activation is greater in subjects with posttraumatic stress disorder (purple).12

Changes in arousal and reactivity, including angry outbursts, are characteristic symptoms of PTSD.34 Anger and PTSD are positively correlated and this correlation is more significant in military than in civilian populations.15,45 Several studies have explored the interactions between anger and PTSD in active duty soldiers. Higher trait anger prior to deployment predicted PTSD symptoms at 2 months after return from deployment.46 However, trait anger at that time did not predict PTSD symptoms at 9 months, supporting trait anger as a PTSD risk factor.46 The relationship between PTSD and aggressive behaviors at 3 months postdeployment was mediated by high trait anger, indicating the importance of anger as a therapeutic target.47 There is evidence that positive aspects of anger (e.g., source of motivation) may be emphasized in the military context.13 At 4 months postdeployment, PTSD symptom scores were positively correlated with anger reaction scores (surrogate measure for trait anger); 21% of the group indicated that they found anger to be helpful often or very often.13 Three months later, this had decreased to 7%. However, perception of anger as helpful was associated with greater physical and mental health difficulties, indicating that it is not a positive influence in the postdeployment context. The authors suggested the clinical value in helping individuals recognize situations where anger is not beneficial and to improve emotion regulation skills.13 A study in veterans also reported that PTSD symptoms predicted occurrence of anger-related symptoms (e.g., irritable affect), but anger did not predict occurrence of PTSD symptoms.48 A strong interest in receiving treatment for problematic anger was noted in a study that included veterans with PTSD.49

There are multiple approaches that have demonstrated the value of treating anger in the context of PTSD, although most studies are small.15,50 Anger management programs can improve anger management skills and provide lasting benefits.15,51,52 An analysis of mechanism(s) of action indicated that improvements in skills related to arousal reduction/calming were most predictive of symptom reductions.53 This suggests that recently developed mindfulness-based interventions for veterans with combat-related PTSD may also decrease anger symptoms.44,54 PTSD treatments, such as cognitive behavioral therapies, can also reduce problematic anger.15 A clinical case series in active duty military with PTSD and problematic anger reported that an individually delivered cognitive behavioral therapy based anger management intervention resulted in clinically significant reductions in symptoms of anger (6/8 cases) and PTSD (5/8 cases).55 A small randomized controlled trial in veterans with combat-related PTSD and problematic anger reported that prolonged exposure therapy and affect regulation therapy had similar efficacy.56 Interventions designed to reduce intimate partner violence also show promise.15,23

In conclusion, there is considerable evidence that anger and PTSD are highly interrelated. However, the nature of the interactions is complex and not fully understood. Functional imaging studies are beginning to examine underlying neural correlates of many aspects. Of particular clinical value will be studies that elucidate mechanisms underlying successful interventions.

1 : Neuroimaging support for discrete neural correlates of basic emotions: a voxel-based meta-analysis. J Cogn Neurosci 2010; 22:2864–2885Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 : Dynamic changes in amygdala psychophysiological connectivity reveal distinct neural networks for facial expressions of basic emotions. Sci Rep 2017; 7:45260Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 : Multivariate neural biomarkers of emotional states are categorically distinct. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2015; 10:1437–1448Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 : Trait anger modulates neural activity in the fronto-parietal attention network. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0194444Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 : Neural activity during the viewing of emotional pictures in veterans with pathological anger and aggression. Eur Psychiatry 2018; 47:1–8Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 : Neural substrates underlying the tendency to accept anger-infused ultimatum offers during dynamic social interactions. Neuroimage 2015; 120:400–411Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 : Neural indicators of interpersonal anger as cause and consequence of combat training stress symptoms. Psychol Med 2017; 47:1561–1572Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 : Accessible neurobehavioral anger-related markers for vulnerability to post-traumatic stress symptoms in a population of male soldiers. Front Behav Neurosci 2017; 11:38Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 : Tracing the neural carryover effects of interpersonal anger on resting-state fMRI in men and their relation to traumatic stress symptoms in a subsample of soldiers. Front Behav Neurosci 2017; 11:252Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 : From provocation to aggression: the neural network. BMC Neurosci 2017; 18:73Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 : Early amygdala activation and later ventromedial prefrontal cortex activation during anger induction and imagery. J Med Psychol (Epub ahead of print, September 29, 2017)Google Scholar

12 : Locus coeruleus activity mediates hyperresponsiveness in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2018; 83:254–262Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 : Can anger be helpful?: soldier perceptions of the utility of anger. J Nerv Ment Dis 2017; 205:692–698Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 : Investigating the relationship between posttraumatic stress symptoms and posttraumatic growth following community violence: the role of anger. Psychol Trauma (Epub ahead of print, October 5, 2017) PubMedGoogle Scholar

15 : Anger and aggression in PTSD. Curr Opin Psychol 2017; 14:67–71Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 : Disentangling the link between posttraumatic stress disorder and violent behavior: Findings from a nationally representative sample. J Consult Clin Psychol 2018; 86:169–178Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 : The impact of post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology on quality of life: the sentinel experience of anger, hypervigilance and restricted affect. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (Epub ahead of print, May 1, 2018)Google Scholar

18 : Deconstructing anger in the human brain. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2017; 30:257–273Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 : What are emotions? a physical theory. Rev Gen Psychol 2015; 19:458–464Crossref, Google Scholar

20 : Exploring the toolkit of emotion: what do sadness and anger do for us? Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2016; 10:11–25Crossref, Google Scholar

21 : How should neuroscience study emotions? by distinguishing emotion states, concepts, and experiences. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2017; 12:24–31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 : Functionalism cannot save the classical view of emotion. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2017; 12:34–36Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 : Anger can help: a transactional model and three pathways of the experience and expression of anger. Fam Process (Epub ahead of print, July 23, 2017)Google Scholar

24 : Basic emotions in human neuroscience: neuroimaging and beyond. Front Psychol 2017; 8:1432Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 : Anger in the classroom: how a supposedly negative emotion can enhance learning. New Dir Teach Learn 2018; 153:37–44Crossref, Google Scholar

26 : When feeling bad is expected to be good: emotion regulation and outcome expectancies in social conflicts. Emotion 2012; 12:807–816Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 : Everything in moderation: the social effects of anger depend on its perceived intensity. J Exp Soc Psychol 2018; 76:12–18Crossref, Google Scholar

28 : When getting angry is smart: emotional preferences and emotional intelligence. Emotion 2012; 12:685–689Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 : Individual differences in the motivational direction of anger. Pers Individ Dif 2017; 119:56–59Crossref, Google Scholar

30 : Drawn to danger: trait anger predicts automatic approach behaviour to angry faces. Cogn Emotion 2017; 31:765–771Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 : The facts on the furious: a brief review of the psychology of trait anger. Curr Opin Psychol 2018; 19:98–103Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 : What triggers anger in everyday life? links to the intensity, control, and regulation of these emotions, and personality traits. J Pers 2016; 84:737–749Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 : On the importance of both dimensional and discrete models of emotion. Behav Sci (Basel) 2017; 7:E66Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 : Finalizing PTSD in DSM-5: getting here from there and where to go next. J Trauma Stress 2013; 26:548–556Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 : A Bayesian model of category-specific emotional brain responses. PLOS Comput Biol 2015; 11:e1004066Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36 : Decoding the nature of emotion in the brain. Trends Cogn Sci 2016; 20:444–455Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 : Affective mapping: an activation likelihood estimation (ALE) meta-analysis. Brain Cogn 2017; 118:137–148Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38 : Understanding emotion with brain networks. Curr Opin Behav Sci 2018; 19:19–25Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39 : Emotions as discrete patterns of systemic activity. Neurosci Lett 2017; S0304-3940(17)30572-4Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40 : Identifying emotions on the basis of neural activation. PLoS One 2013; 8:e66032Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41 : Discrete neural signatures of basic emotions. Cereb Cortex 2016; 26:2563–2573Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42 : Distributed affective space represents multiple emotion categories across the human brain. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2018; 13:471–482Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43 : Individual differences in cognitive reappraisal use and emotion regulatory brain function in combat-exposed veterans with and without PTSD. Depress Anxiety 2017; 34:79–88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44 : A pilot study of mindfulness-based exposure therapy in OEF/OIF combat veterans with PTSD: altered medial frontal cortex and amygdala responses in social-emotional processing. Front Psychiatry 2016; 7:154Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45 : Assessment and treatment of posttraumatic anger and aggression: a review. J Rehabil Res Dev 2012; 49:777–788Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46 : Anger: cause or consequence of posttraumatic stress? a prospective study of Dutch soldiers. J Trauma Stress 2014; 27:200–207Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47 : Aggression in US soldiers post-deployment: associations with combat exposure and PTSD and the moderating role of trait anger. Aggress Behav 2015; 41:556–565Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48 : Characterizing anger-related affect in individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder using ecological momentary assessment. Psychiatry Res 2018; 261:274–280Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49 : An investigation of treatment engagement among returning veterans with problematic anger. J Nerv Ment Dis 2017; 205:119–126Medline, Google Scholar

50 : Anger and aggression treatments: a review of meta-analyses. Curr Opin Psychol 2018; 19:65–74Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51 : Using a mobile application in the treatment of dysregulated anger among veterans. Mil Med 2017; 182:e1941–e1949Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52 : Effectiveness of an anger control program among veterans with PTSD and other mental health issues: a comparative study. J Clin Psychol 2018 (Epub ahead of print, April, 26, 2018)Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53 : Peeking into the black box: mechanisms of action for anger management treatment. J Anxiety Disord 2014; 28:687–695Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54 : A pilot study of the effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and brain response to traumatic reminders of combat in Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Front Psychiatry 2017; 8:157Medline, Google Scholar

55 : Effectiveness of an anger intervention for military members with PTSD: a clinical case series. Mil Med 2018Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56 : Randomized clinical trial pilot study of prolonged exposure versus present centred affect regulation therapy for PTSD and anger problems with male military combat veterans. Clin Psychol Psychother 2018 (Epub ahead of print, April 23)Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar