Bilingualism and Dementia

SIR: Language loss is one of the most debilitating aspects of dementia.1 Word-finding difficulty is often among the first abnormalities in dementia, followed by decreased verbal fluency, naming, and comprehension.

The ability to maintain fluency in more than one language decreases with advancing age.2 Older people may have a tendency to retreat to a single language, even those with a lifetime of bilingualism. Moreover, older bilingual individuals may have special problems due to the effects of cross-language interference. These effects in aging bilingual persons can be further exaggerated in those who develop dementia.

Methods and Results

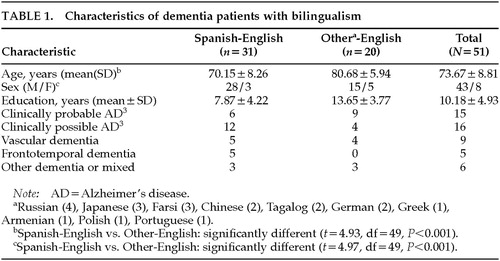

In our UCLA-affiliated clinics, we identified 51 patients who reported routine use of another language, as well as varying fluency in English, and who presented for an evaluation because of progressive memory or cognitive problems. Patients' characteristics are outlined in Table 1. Language difficulty complicated mental status testing; however, the patients could be characterized as moderately impaired, community-dwelling patients able to handle their routine activities of daily living. All patients were regularly exposed to English as a second language after age 13. The most common situation involved the use of the original language with family and friends and the use of at least a rudimentary amount of English outside the home.

Because of the variety of languages and baseline English fluency, language testing could not be done in many of these patients. Nevertheless, despite patients' differences in educational level, age at acquisition of English, frequency of use, and baseline fluency in English, all caregivers reported a greater preference of the patients for their original language and decreased conversation in English. In characterizing the errors made by patients, most caregivers described a tendency for words and phrases from the mother language to intrude into English conversational speech.

Discussion

In this survey, bilingual dementia patients tended to asymmetrical language impairment with preferential preservation and use of the first acquired language.4 Studies in aphasic patients from strokes and other brain lesions show that recovering language patterns are most commonly synergistic; recovery in one language is accompanied by recovery in another. Many bilingual aphasic patients, however, recover differentially in one language. In these circumstances, the language most recovered may be the earliest acquired language, the language of greater use, or the language spoken in the patient's environment. In dementia, recently learned information is retained the least and older, more remote information is often relatively preserved, consistent with a regression toward the predominant use of the patient's earliest language.

In dementia, a retreat to the original language could result from an exacerbation of the cross-language difficulties that typically increase with age. “Cross-language interference” refers to deviations from the language being spoken due to the involuntary influence of the “deactivated” language. People who are bilingual never totally deactivate either of their two languages, and this can result in interference or intrusions, particularly from the dominant language into the other one. Dementia patients tend to mix languages, and they have special problems with language separation.2

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The project described above was supported by National Institute on Aging Alzheimer's Disease Center Grant AG10123, Alzheimer's Disease Research Center of California, and the Sidell-Kagan Foundation.

|

1 Cummings JL, Benson DF, Hill MA, et al: Aphasia in dementia of the Alzheimer type. Neurology 1985; 35:394–397Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Hyltenstam K, Obler LK: Bilingualism Across the Lifespan: Aspects of Acquisition, Maturity, and Loss. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1989Google Scholar

3 McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al: Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group. Neurology 1984; 34:939–944Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Paradis M: The Assessment of Bilingual Aphasia. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum, 1987Google Scholar