Dissociative Flashbacks After Right Frontal Injury in a Vietnam Veteran With Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Abstract

A Vietnam veteran with a combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder developed recurrent dissociative flashbacks (related to the atrocities of a specific war incident) several months after suffering a traumatic brain injury. CT disclosed a small lesion in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. SPECT demonstrated more extensive functional changes in prefrontal and anterior paralimbic brain regions, mainly in the right hemisphere. This case further implicates the provocative effect of physical stimuli (brain damage) in reawakening old dormant memories and the preferential role of the right hemisphere for the storage of traumatic memories.

One central issue in the study of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is the nature of the stressor.1 Although in most instances environmental stressors are sufficient to induce the constellation of intrusive and avoidance stress symptoms,1 on certain occasions PTSD results from the interaction of psychological and biological mechanisms.2–6

The effects of brain damage on the course of PTSD are still controversial, and debate has centered on the possible role of head trauma in pathogenesis.7 Some authors argue that mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) and PTSD are mutually exclusive disorders8 or consider that brain trauma (blast concussion) in veterans may protect them from PTSD9 because loss of consciousness prevents the encoding and consolidation of traumatic memories, presumably by altering several neurotransmitter systems (such as glutamate).10 Other authors report quantitative electroencephalographic changes indicative of mild TBI in combat veterans with chronic PTSD and a remote history of blast injury.11 Still others variously report a high frequency (24%) of PTSD after mild TBI;12 the occurrence of PTSD associated with TBI13–15 or anoxic encephalopathy,16 even though affected patients did not consciously recall the circumstances of injuries; or the reactivation of traumatic memories among patients who suffer mild, apparently indolent, TBI.17

We describe here the case of a Vietnam veteran with a history of PTSD who after suffering a moderate TBI developed dissociative flashbacks related to the experiences of war.

CASE REPORT

C.G., a 49-year-old Vietnam War veteran (a professional soldier from the United Kingdom who served with the allied forces), was admitted to the emergency room with excruciating right orbital headache, chest discomfort, and recurrent episodes of “confusion related to war experiences.” Nine months before admission, he had been hit by a car while walking and sustained a closed head trauma with a right frontal scalp laceration. Clinical records from another hospital revealed that C.G. had had a transient loss of consciousness and a posttraumatic amnesia of about 30 hours. His past medical history was also remarkable for a myocardial infarction 7 years before the TBI, angina, peripheral vascular disease, and a transient ischemic attack causing a left hemiparesis (a CT scan was negative). In addition, C.G. described a number of life-threatening experiences during his years in Vietnam, but the most stressful incident was the death of his Vietnamese partner and their young daughter, who were killed, together with other people, during an attack by the enemy on a refugee village. In this incident, C.G. was captured and subjected to torture and interrogations under the effects of a mind-altering drug (scopolamine) over a 1-week period.

After the traumatic incident, C.G. met only the DSM-IV18 criterion “A” for PTSD (exposure to a severe traumatic event), and although he has intermittently had overt symptoms of PTSD (reexperiencing the trauma on exposure to external cues related to the war experience, dreams reminiscent of the trauma, outbursts of anger), he did not show the other behavioral symptoms (avoidance, numbing, exaggerated startle response) necessary to fulfill the diagnostic DSM-IV criteria for PTSD. In particular, he never experienced dissociative flashback phenomena before the TBI. Despite the disastrous outcome of the village attack, C.G. said: “There were no things to try to remove because I didn't remember it before the accident [TBI].”

His medical and psychiatric problems led to his early retirement to a rural area in Málaga, Spain. There he met his current wife, and both now devoted much time to the breeding of horses. He also served his community as a volunteer in an organization serving the mentally handicapped. His wife indicated that he had abused alcohol to control anxiety symptoms and maladaptive personality changes (suspiciousness, restricted range of emotional expression, need for admiration), but he never sought psychiatric treatment before suffering the TBI.

During the current hospitalization, C.G presented several flashback episodes that were witnessed by the attending nurse and neurology staff. The content of the dissociative flashbacks was extremely realistic and clearly reproduced the index incident that C.G. had lived while he was in Vietnam. He apparently experienced frightening visual and auditory hallucinations, describing the attack on the refugee village in great detail. During the dissociative episodes, he acted as if he were back in Vietnam, and on one occasion he even wrote: “I can't go into great detail for ‘security reasons.’ I saw men burnt alive in a vehicle and a whole village (mainly children and old people) killed with gas. I was caught and tortured…but escaped…. The bastards!!!”

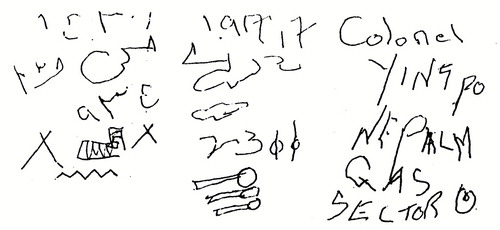

Also, he automatically drew several badly decipherable symbols and wrote words with high negative emotional salience (e.g., “napalm gas”), as shown in Figure 1. The flashbacks lasted several minutes, occurred two or three times a day, and were accompanied by hypervigilance, agitation, confusion, and somatic symptoms of anxiety. Between episodes, C.G. could not recall the details of the dissociation phenomena, but his thoughts were well organized and there was no evidence of illogical thinking or loosening of associations. Neurological examination was always normal. His score on the Mini-Mental State Examination19 was within normal limits (28/30). The Impact of Event Scale (IES)20 was used to measure intrusive thoughts and avoidance behavior associated with either the TBI or the war incident (the refugee village attack). He obtained high scores on the IES; for the TBI incident his total IES score was 44 (intrusion subset score=29; avoidance subset score=15), whereas for the war incident his total IES score was 51 (intrusion subset score=33; avoidance subset score=18).

Although he had posttraumatic amnesia, not recalling anything about the circumstances of the accident, it is possible that he learned details of the traumatic event through information verbally mediated by witnesses and family members.21 He had intrusive thoughts and images of the street where he was run over by the car, he avoided talking about the accident, and he commented that his facial scars were continuous reminders of the injury. On the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression,22 his score was 13 points. He was also administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II23) and was found to meet criteria for paranoid, schizoid, and narcissistic personality disorders. While an inpatient, C.G. was treated with carbamazepine (800 mg/day) and the dissociative flashbacks remitted after a few days.

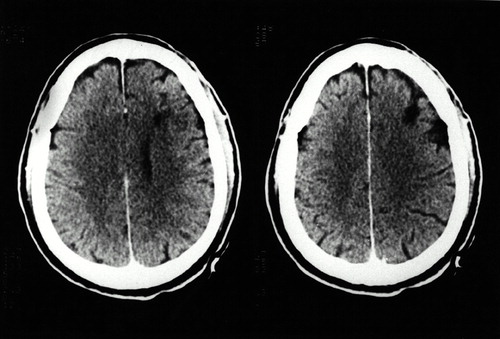

Serial EEGs carried out between dissociative episodes were always normal. A CT scan of the brain (Figure 2) showed a low-density lesion in the right dorsolateral frontal lobe (Brodmann area 6). Regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) was studied in C.G., when he was free of medication and between dissociative episodes, with [99mTc]HMPAO and SPECT, using an Elscint Apex 609 RG gamma camera. Focal blood flows were analyzed semiquantitatively in regions of interest (ROIs; circular, 4×4 pixels), which were placed in cortical and subcortical regions of seven successive transaxial slices.24 The total number of ROIs was combined to create eight cortical areas: inferior frontal cortex, superior frontal cortex, anterior temporal cortex, mesial temporal cortex, posterior temporal cortex, anterior cingulate, parietal cortex, and occipital cortex. Additional ROIs were placed in the cerebellum, thalamus, and basal ganglia (caudate nucleus). An rCBF was calculated for each ROI as the average activity in the region divided by the activity in the cerebellum (region [right−left] average/cerebellum).25 According to our own previous data from normal subjects (mean ratio: 1.00±0.03), ratios below 0.93 were considered abnormal.24

The most marked rCBF decreases were seen in the anterior temporal cortex (0.78) and superior frontal cortex (0.78). Less robust decrements (but always 2 SD below the mean of normal control subjects) were seen in the inferior frontal cortex (0.91), parietal cortex (0.91), and posterior temporal cortex (0.92). Decrements were always more prominent in the right than the left hemisphere. On the other hand, rCBF increases were seen in anterior cingulate (1.13), caudate nucleus (1.14), and thalamus (1.10). No relevant changes were seen in the mesial temporal (amygdala) and occipital cortices.

DISCUSSION

The present case illustrates the interaction between environmental and biological factors in the pathogenesis of PTSD. Although trauma response usually correlates with exposure,1 it is clear that certain individuals (those with a history of previous trauma) are more vulnerable to the development of stress symptoms.26,27 Following exposure to a hostile environment (extreme war-zone experiences) our patient developed some symptoms of PTSD expressed by occasional reexperiencing and dreams reminiscent of the traumatic experience, but he did not develop a full-blown PTSD until he suffered the TBI. Moreover, several months after the TBI he presented, for the first time, recurrent dissociative flashbacks. It is possible that prior to TBI our patient was suffering from a denied or previously unrecognized PTSD1—related to war, myocardial infarction,3 or both—that reached its salient clinical expression only after the TBI. Several months after the TBI, when C.G. was interviewed between dissociative episodes, he met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for PTSD, the content of stress symptoms being related to the immediate and long-term consequences of TBI even though he had no conscious recollections of details of the accident. He also demonstrated a reactivation of old traumatic memories of war. Intrusive and avoidance symptoms of both conditions (TBI and war) were equally distressing to C.G, though the dissociative flashbacks were invariably related to the atrocities of a specific war incident.

Dissociative flashbacks may simply reflect behavioral disinhibition secondary to TBI, but we hypothesize that C.G. was sensitized during war and that a subsequent stressor (TBI) was sufficient to trigger a complex behavioral outburst (dissociative flashbacks). In our view, behavioral sensitization would also explain the enhancement of response magnitude after repeated exposure to traumatic stimuli.28 Thus, contrary to both previous theories arguing that TBI might “protect” from PTSD8–10 and cases describing the disappearance of intrusive PTSD symptoms after right frontal damage,29 the present case illustrates the role of brain damage not only in producing a PTSD (related to TBI), but also in reawakening old traumatic memories related to war. It is important to note, however, that because C.G. was also repeatedly exposed to several environmental and psychological stressors, the etiology of the dissociative flashbacks cannot be definitively determined.

The emergence of PTSD symptoms related to TBI without conscious recollection of the traumatic incident, as seen in C.G., has already been noted among previous patients with head trauma–related PTSD.13–16 This memory dissociation probably indicates that traumatic memories can be stored and reactivated by a wide variety of reminders, even when brain structures implicated in the modulation of declarative memories are dysfunctional.13–16 This type of memory dissociation in PTSD provides further support for the theory postulating the existence of two or more independent memory systems, each handling a different type of memory function.30 Thus, it seems that in the case of C.G, the structural focal lesion in the right superior prefrontal cortex (Brodmann area 6), causing amnesia for details of the TBI, acted in concert with the bilateral dysfunction of anterior paralimbic regions (orbitofrontal, anterior temporal, and cingulate cortices) not only to favor the intrusion of memories related to previous traumatic experiences, but also to trigger dissociative flashbacks.

The nature of the functional changes documented in the SPECT of our patient is difficult to determine. The similarity between the topographical distribution of reduced rCBF at baseline in patient C.G. and that reported in PET studies in patients with combat-related PTSD31 and in SPECT studies in patients with PTSD linked to other psychological or environmental traumatic events32–34 raises the possibility that reduced rCBF in our patient occurred in response to nonbiological stressors. Nevertheless, rCBF decrements in C.G. in interconnected anterior regions of the right hemisphere (temporal pole and prefrontal cortex) were more marked than in other regions, thus suggesting a close relationship between the structural damage in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the functional changes documented in the SPECT.

The hemispheric lateralization of functional changes during traumatic remembrance is interesting. Accumulating empirical evidence suggests a preferential role of the right hemisphere for the storage of negative emotional memories,35 and a right temporofrontal neural network mediating the retrieval of emotional autobiographical memories has been suggested.36,37 Several PET studies using scrip-driven imagery symptom provocation paradigms (i.e., the content of a personal traumatic experience) in patients with PTSD found right-sided38 or bilateral39,40 increments in rCBF in limbic, anterior paralimbic, and visual regions areas during the recall of traumatic memories.

Berthier and colleagues17 reported the reactivation of PTSD symptoms after TBI in two women who had recovered from PTSD linked to histories of sexual abuse during adolescence. Thus, it seems that the reexperiencing of autobiographical traumatic memories may be elicited not only by environmental and psychological cues (as regularly occurs in PTSD), but also by biological factors such as TBI.17 Dysfunction of certain regions of the prefrontal cortex and anterior temporal cortex involved with old episodic memories may play a role in the occurrence of dissociative flashbacks.

FIGURE 1. CG.'s automatic drawing of badly decipherable symbols (left and middle) and writing of words with high negative emotional value (right).

FIGURE 2. Computed tomography scan (axial plane) showing a low-density lesion in the right anterior–superior prefrontal cortex (Brodmann area 6) and its underlying white matter

1 Tomb DA: The phenomenology of post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1994; 17:237–250Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Andreasen NC: Posttraumatic stress disorder: psychology, biology, and the Manichean warfare between false dichotomies (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:963–965Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Doerfler LA, Pbert L, DeCosimo D: Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder following myocardial infarction and coronary artery bypass surgery. Hosp Gen Psychiatry 1994; 16:193–199Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Cassiday KL, Lyons JA: Recall of traumatic memories following cerebral vascular accident. J Trauma Stress 1992; 5:627–631Crossref, Google Scholar

5 Briggs AC: A case of delayed post-traumatic stress disorder with “organic memories” accompanying therapy. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 163:828–830Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Davidoff DA, Kessler HR, Laibstain DF, et al: Neurobehavioral sequelae of minor head injury: a consideration of post-concussive syndrome versus post-traumatic stress disorder. Cognitive Rehabilitation 1988; March/April:8–13Google Scholar

7 Epstein RS, Ursano RJ: Anxiety disorders, in Neuropsychiatry of Traumatic Brain Injury, edited by Silver JM, Yudofsky SC, Hales RE. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994, pp 285– 311Google Scholar

8 Sbordone RJ, Liter JC: Mild traumatic brain injury does not produce post-traumatic stress disorder. Brain Inj 1995; 9:405–412Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Mayou R, Bryant B, Duthie R: Psychiatric consequences of road traffic accidents. BMJ 1993; 307:647–651Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 O'Brien M, Nutt D: Loss of consciousness and post-traumatic stress disorder: a clue to etiology and treatment (editorial). Br J Psychiatry 1998; 173:102–104Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Trudeau DL, Anderson J, Hansen LM, et al: Findings of mild traumatic brain injury in combat veteran with PTSD and a history of blast concussion. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 10:308–313Link, Google Scholar

12 Bryant RA, Harvey AG: Relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder following mild traumatic brain injury. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:625–629Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 McMillan TM: Post-traumatic stress disorder and severe head injury. Br J Psychiatry 1991; 159:431–433Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Horton AM Jr: Posttraumatic stress disorder and mild head injury: follow-up of a case. Percept Mot Skills 1993; 76:243–246Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 McNeil JE, Greenwood R: Can PTSD occur with amnesia for the precipitating event? Cognitive Neuropsychiatry 1996; 1:239–246Google Scholar

16 Krikorian R, Layton BS: Implicit memory in posttraumatic stress disorder with amnesia for the traumatic event. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 10:359–362Link, Google Scholar

17 Berthier ML, Kulisevsky J, Fernández Benitez JA, et al: Reactivation of posttraumatic stress disorder after minor head injury. Depress Anxiety 1998; 8:43–47Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

19 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W: Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 1979; 41:209–218Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Saigh PA: Verbally mediated childhood post-traumatic stress disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1992; 161:704–706Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Hamilton MA: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders: SCID II (version 1.0). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

24 Berthier ML, Posada A, Puentes C, et al: Brain SPECT imaging in transcortical sensory aphasias: the functional status of the left perisylvian language cortex. Eur J Neurol 1997; 4:551–560Crossref, Google Scholar

25 Mayberg HS, Lewis PJ, Regenold W, et al: Paralimbic hypoperfusion in unipolar depression. J Nucl Med 1994; 35:929–934Medline, Google Scholar

26 Bremner JD, Southwick SM, Johnson DR, et al: Childhood physical abuse and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:235–239Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Goenjian AK, Najarian LM, Pynoos RS, et al: Posttraumatic stress reactions after single and double trauma. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 90:214–221Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Southwick SM, Bremner D, Krystal JH, et al: Psychobiological research on post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1994; 17:251–264Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Freeman TW, Kimbrell T: A “cure” for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder secondary to a right frontal lobe infarct: a case report. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2000; 13:99–102Google Scholar

30 Bauer RM, Tobias B, Valenstein E: Amnesic disorders, in Clinical Neuropsychology, 3rd edition, edited by Heilman KM, Valenstein E. New York, Oxford University Press, 1993, pp 523–602Google Scholar

31 Bremner JD, Innis RB, Ng CK, et al: PET measurement of central metabolic correlates of yohimbine administration in posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:246–256Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 Woods SW: Regional cerebral blood flow imaging with SPECT in psychiatric disease: focus on schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, and substance abuse. J Clin Psychiatry 1992; 53(suppl):20–25Google Scholar

33 De Cristofaro MTR, Sessarego A, Pupi A, et al: Brain perfusion abnormalities in drug-naive lactate-sensitive panic patients: a SPECT study. Biol Psychiatry 1993; 33:505–512Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 Lucey JV, Costa DC, Adshead G, et al: Brain blood flow in anxiety disorders: OCD, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder on 99m-TcHMPAO single photon emission tomography (SPET). Br J Psychiatry 1997; 171:346–350Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 Schiffer F, Teicher MH, Papanicolaou AC: Evoked potential evidence for right brain activity during the recall of traumatic memories. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1995; 7:169–175Link, Google Scholar

36 Calabrese P, Markowitsch HJ, Durwen HF, et al: Right temporofrontal cortex as critical locus for the ecphory of old episodic memories. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996; 61:304–310Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 Fink GR, Markowitsch HJ, Reinkemeier M, et ral representation of one's own past: neural networks involved in autobiographical memory. J Neurosci 1996; 16:4275–4282Google Scholar

38 Rauch SL, van der Kolk BA, Fisler RE, et al: A symptom provocation study of posttraumatic stress disorder using positron emission tomography and script-driven imagery. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:380–387Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39 Shin LM, McNally RJ, Kosslyn SM, et al: Regional cerebral blood flow during script-driven imagery in childhood sexual abuse-related PTSD: a PET investigation. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:575–584Medline, Google Scholar

40 Bremner JD, Narayan M, Saib LH, et al: Neural correlates of memories of childhood sexual abuse in women with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J. Psychiatry 1999; 156:1787–1795Google Scholar