A “Cure” for Chronic Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Secondary to a Right Frontal Lobe Infarct

Abstract

A 48-year-old combat veteran sustained a right frontal cerebral infarct at the age of 45 years. The patient's family reports that prior to the infarct he had a preoccupation with memories of combat, as well as nightmares, avoidance of reminders, and multiple arousal symptoms. Since his recovery from the infarct, the patient and his family continue to relate significant arousal symptoms but deny any continued history of preoccupation with traumatic memories, reminder avoidance, or nightmares. The resolution of a limited number of symptoms in this patient following damage to the right frontal cortex suggests that some of the symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder may be amenable to current biological interventions.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a common and often debilitating neuropsychiatric illness. The disorder is acquired following exposure to severe emotional trauma. Affected individuals present with elevated levels of arousal, avoidance of reminders relating to the traumatic event, and reexperiencing symptoms that take the form of nightmares and intrusive memories of the traumatic event. The symptoms may last for many years in some patients,1 and numerous studies attest to the marked morbidity associated with the condition.2,3 The reexperiencing symptoms of PTSD account for a substantial portion of this morbidity, and these symptoms relate directly to the recollection of traumatic events experienced by the affected individual. It is of interest that these reexperiencing symptoms can be evoked in the laboratory with the use of pharmacological agents such as yohimbine4 and lactate,5 and autobiographical scripts of traumatic events have been used to examine changes in regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) in patients with PTSD.6

Extensive investigations into memory have distinguished multiple classes of memories, including semantic, procedural, implicit, explicit, and autobiographical memory.7 Autobiographical memory is typically described as memory preserving knowledge of the emotional and spatiotemporal context in which a personal event takes place,8 as compared with semantic memory, which is most often described as the recollection of facts abstracted from the experience in which learning occurred. Impairment in autobiographical memory following a number of regional cerebral insults has been described. Damage to the frontal cortex, in particular the right frontal cortex, has been associated most often with impairments in autobiographical memory.9

Although autobiographical memory plays a limited role in the majority of psychiatric illnesses, it clearly plays a significant role in the manifestation of reexperiencing symptoms associated with chronic PTSD. The role of traumatic autobiographical memory in PTSD is unique. In no other psychiatric illness does the recollection of traumatic past personal events play such a pivotal role in diagnostic classification and disease morbidity. Given this, a question arises: How would an acquired autobiographical memory deficit affect a patient with chronic PTSD?

We describe a patient who presented originally for evaluation and treatment of his persistent anxiety symptoms. His wife related a long history of arousal, avoidance, and reexperiencing symptoms following combat in the Vietnam War. At the age of 45 years, he suffered an infarct to the right frontal lobe and after his recovery no longer suffered from nightmares or intrusive recollections of his combat experience. However, he did continue to manifest arousal symptoms in the form of exaggerated startle, irritability, and insomnia.

CASE REPORT

The patient, a right-handed Vietnam combat veteran, presented initially at age 48 years for evaluation for admission to a PTSD rehabilitation program. He and his wife related a chronic history of arousal symptoms, including irritability, insomnia, and generalized anxiety, that had persisted since the end of the Vietnam War. On further questioning, the patient's wife described the patient's nightmares and intrusive recollections of the war, which had been present up to the time he suffered an acute cerebral infarct at age 45. At that time, the patient suddenly developed generalized weakness, headache, and a mild weakness on his left side that resolved over a period of several days.

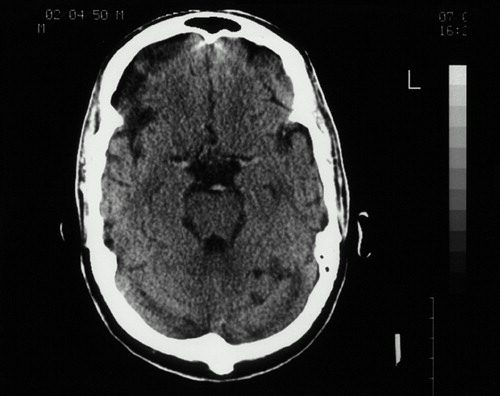

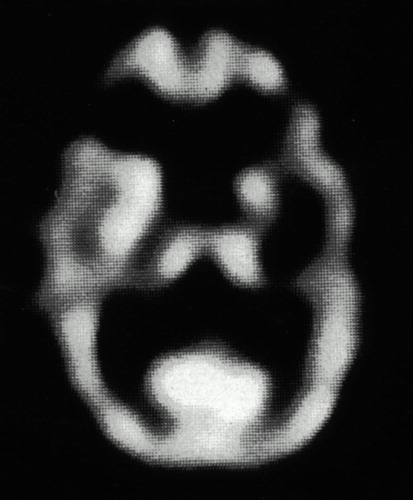

At the time of the initial psychiatric interview, the patient related a number of depressive symptoms, generalized anxiety, and periods of verbal and physical aggression in association with minor irritants. The patient denied any nightmares, intrusive recollections of the war, or any effort to avoid reminders of the war. His responses to these questions suggested very limited personal memory for most past events, including his war experiences. His presentation was notable for marked motor dysprosody, although sensory prosody was intact to bedside testing. Computed tomography of the head done at the time of the infarct revealed evidence of right frontal damage (Figure 1). A cerebral [99mTc]HMPAO SPECT scan completed 3 years after the initial infarct showed decreased rCBF in the right frontal cortex at the location of the infarct (Figure 2). Normalization of rCBF to a mean cerebellum rCBF value demonstrated a 43% reduction of right frontal rCBF compared with the left.

Neuropsychological testing at the time of the interview 3 years after the infarct showed average intelligence, with a Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised Full Scale IQ of 92 (Performance IQ=91, Verbal IQ=93), although individual subtest performances suggested disruptions in graphomotor efficiency, problem-solving speed, logical-sequential reasoning, and spatial cognition. Estimates of general memory functioning fell well below his measures of intellectual function, primarily because of retrieval difficulty in spontaneous and delayed free recall of narrative verbal information. Moderate dysfunction was noted on the Trail Making Test part B and the complex Tactual Performance Test. The patient completed the Autobiographical Memory Interview,10 obtaining scores on personal semantic events of 14.5/21 (childhood), 17.5/21 (adulthood), and 19/21 (recent), and on autobiographical incidents of 0/9 (childhood), 3/9 (adulthood), and 7/9 (recent). These results reveal a relative decrement in remote and past autobiographical memory function and an improved recall of more recent autobiographical material—a pattern similar to that in another reported case of acquired autobiographical memory impairment following a right frontal lobe infarct.9 The patient also completed the Davidson Trauma Scale, a self-report instrument for PTSD symptoms. His score on the intrusion (reexperiencing) subscale was 0; on the avoidance/numbing subscale, 39; and on the hyperarousal subscale, 29. The avoidance/numbing subscale score was entirely made up of his positive responses to questions about emotional numbing; he gave no positive responses to questions about avoidance of reminders.

DISCUSSION

This patient's family described the classic constellation of arousal, avoidance, and reexperiencing symptoms necessary to make the diagnosis of PTSD, all of which were present prior to a right frontal infarct. Three years after this cerebral infarct, the patient was examined and found to have significantly impaired autobiographical memory and no longer to meet criteria for PTSD because of the absence of reexperiencing and avoidance symptoms. However, although his reexperiencing and avoidance symptoms had dissipated, he continued to manifest symptoms of exaggerated autonomic arousal. This case suggests an association between autobiographical memory, the reexperiencing symptoms of PTSD, and intact right frontal cortical function. Furthermore, the case suggests that exaggerated autonomic arousal can persist independently of reexperiencing symptoms in patients with chronic PTSD.

The association between reexperiencing symptoms and intact right-sided cortical function has been reported previously. In a provocation study of patients with PTSD, Rauch et al.6 described increases in rCBF as measured by positron emission tomography in PTSD patients exposed to autobiographical audiotaped scripts of traumatic events. The authors reported increased rCBF in right-sided limbic and paralimbic structures, including the right medial orbitofrontal cortex.

Other provocation studies of PTSD patients that did not use autobiographically driven reminders11 have not described increased lateralized frontal activation. However, PET studies of autobiographical memory in normal subjects12 have suggested that a neural network primarily involving right-sided limbic and frontal hemispheric structures is associated with the recall of affect-laden autobiographical memory. A case report of damage to the right temporofrontal cortex due to herpes infection, with resulting autobiographical memory deficit, has been previously described by Calabrese et al.9 These findings support the role of right hemispheric structures, especially limbic and frontal regions, in the recall of personal events and suggests that damage to these areas could result in the inability to recall traumatic personal memories.

Our patient shows a continued impairment in autobiographical memory after his infarct, and because he no longer has either reexperiencing symptoms or avoidance symptoms, he no longer meets criteria for PTSD. However, he still manifests arousal symptoms and provides clinical evidence that arousal and reexperiencing symptoms in PTSD patients may be mediated by distinct, though overlapping, neural substrates.

This case exemplifies the relationship between known cortical substrates of autobiographical memory and PTSD and suggests biological interventions into the illness. Recently, McCann et al.13 reported attenuation of cerebral hypermetabolism and improvement in PTSD symptoms following low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the right prefrontal cortex in an attempt to inhibit right frontal cortical activity. It is likely that further work with this possible new treatment modality will provide additional evidence of the neural circuitry underlying the spectrum of PTSD symptoms.

FIGURE 1. Computed tomography of the patient's head done at the time of the infarct, revealing evidence of right frontal damage

FIGURE 2. Cerebral [99mTc]HMPAO SPECT scan completed 3 years after the initial infarct, showing decreased regional cerebral blood flow in the right frontal cortex at the location of the infarct

1 Solomon Z, Neria Y, Ohry A, et al: PTSD among Israeli former prisoners of war and soldiers with combat stress reaction: a longitudinal study. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:554–559Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Crowson J, Frueh B, Beidel D, et al: Self-reported symptoms of social anxiety in a sample of combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Anxiety Disord 1998; 12:605–612Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 David D, Kutcher G, Jackson E, et al: Psychotic symptoms in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:29–32Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Southwick SM, Krystal JH, Morgan CA, et al: Abnormal noradrenergic function in posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:266–274Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Jensen CF, Keller TW, Pescind ER, et al: Behavioral and neuroendocrine responses to sodium lactate infusion in subjects with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:266–268Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Rauch S, van der Kolk BA, Fisler RE, et al: A symptom provocation study of PTSD using PET and script-driven imagery. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:380–387Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Bjork E, Bjork R (eds): Memory. New York, Academic Press, 1996Google Scholar

8 Tulving E: Elements of Episodic Memory. New York, Oxford University Press, 1983Google Scholar

9 Calabrese P, Markowitsch H, Durwen H, et al: Right temporofrontal cortex as critical locus for the ecphory of episodic memories. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996; 61:304–310Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Greene J, Hodges J, Baddeley A: Autobiographical memory and executive function in early dementia of Alzheimer type. Neuropsychologia 1995; 33:1647–1670Google Scholar

11 Shin LM, Kosslyn SM, McNally RJ, et al: Visual imagery and perception in posttraumatic stress disorder: a positron emission tomography investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:233– 241Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Fink G, Markowitsch HJ, Reinkemeier M, et al: Cerebral representation of one's own past: neural networks involved in autobiographical memory. J Neurosci 1996; 16:4275–4282Google Scholar

13 McCann UD, Kimbrell TA, Morgan CM, et al: Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for PTSD: two case reports. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:276–279Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar