Frequency and Characteristics of Anxiety Among Patients With Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to assess the cross-sectional prevalence and characteristics of anxiety among patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD), as compared with patients with frontotemporal dementia (FTD), patients with vascular dementia (VaD), and normal control subjects. The authors used the anxiety subscale of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), an instrument with established reliability and validity, to compare patients. Patients were identified in a query of the UCLA Alzheimer's Disease Center database and included 115 patients with probable AD, 43 patients with VaD, 33 patients with FTD, and 40 normal, elderly control subjects. Descriptive statistics were generated, and partial correlations, controlling for Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score, were performed between the anxiety subscale and other behavioral features as measured by the NPI and the Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ). Relationships between cognitive status (as indicated by MMSE score) and anxiety were explored. Anxiety was reported more commonly in patients with VaD and FTD than in patients with AD. These differences remained significant (P<0.01) in an analysis of variance (ANOVA) after adjusting for age, age at onset, educational level, and MMSE score. In AD, anxiety was inversely related to MMSE score (i.e., worse with more severe dementia), was more prevalent among patients with a younger age at onset (under age 65), and correlated with disability as measured by the FAQ score. These data suggest that anxiety is common among patients with diverse forms of dementia. In AD, anxiety is most common in those with more severe cognitive deterioration and an earlier age at onset.

Neuropsychiatric disturbances are a major feature of a variety of dementing illnesses, including Alzheimer's disease (AD), vascular dementia (VaD), and frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Behavioral abnormalities may contribute significantly to decreased quality of life, increased morbidity, higher levels of caregiver distress, and the decision to institutionalize a patient.1–3 In the few studies devoted to this topic, anxiety is identified as an important behavioral symptom in AD and other forms of dementia, and it may be a prominent feature early in the course of the disease.4 In studies commenting on anxiety in AD patients, the cross-sectional relevance varies from 25% to 75%.5–10 However, anxiety in dementia has not undergone much study, and the literature offers little information about its features and any associations it might have with other patient characteristics and behavioral changes. It also has been difficult to assess anxiety separately from common comorbid behaviors such as depression, agitation, and irritability. Anecdotal evidence suggests associations between anxiety and agitation, irritability, pacing, and depression; it is not known whether such associations are specific to AD or are present in other forms of dementia as well. In one study of patients with AD, the presence of a generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) was associated with greater levels of depression, tearfulness, irritability, overt aggression, and mania.11

In this study, an observational cross-sectional analysis, we used the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI)12,13 to assess the prevalence and characteristics of anxiety in patients with AD, VaD, FTD, and normal control subjects. (A copy of the NPI may be obtained from the correspondence author.) Data on a sufficient number of patients with AD were available to allow evaluation of the association of anxiety with other behavioral disturbances as measured by the NPI, cognitive decline as measured by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),14 and instrumental activities of daily living as measured by the Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ).15

METHOD

Patients

The study population consisted of 191 subjects with dementia and 40 normal control subjects obtained from a query of the UCLA Alzheimer's Disease Center database for all subjects who met inclusion criteria between 1995 and 1999. All subjects and their caregivers had given written informed consent before medical information was entered into the database for future research purposes. The subjects with dementia had presented to the University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center, the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and the UCLA Drew-King Memory and Cerebral Function Clinic for an initial dementia evaluation between 1995 and 1999. The spouse or other family member familiar with the patient served as the informant for the NPI.12,13 The dementia evaluation included a complete medical history, physical and neurological examinations, and neuropsychological testing, including, among other instruments, the MMSE14 and the FAQ.15 Additional testing included magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and routine blood tests, including a complete blood count, determinations of thyroid-stimulating hormone and vitamin B12 levels, and a serological test for syphilis. For many subjects, single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and electroencephalography were performed.

All 191 dementia subjects met the following inclusion criteria: completion of a full dementia evaluation as outlined above; the presence of dementia as defined by DSM-IV criteria; an established diagnosis of either probable AD, VaD, or FTD by current criteria;16–19 completion of the NPI by a caregiver of each dementia subject at the time of the dementia evaluation; and being stable on any medications (e.g., antihypertensive medications) for one month before the neurological and psychological assessments.

Exclusion criteria included the presence of clinically significant systemic diseases other than dementia that could independently contribute to anxiety, such as cerebrovascular disease (which was not applied as an exclusion criterion for patients with a diagnosis of VaD) or thyroid dysfunction (i.e., hyper- or hypothyroidism); the presence of a delirium by DSM-IV criteria; a history of abuse of alcohol or other substance; a history of head trauma with loss of consciousness; and a history of psychiatric illness that predated the onset of the dementia (e.g., depression, generalized anxiety disorders, and panic attacks). One hundred and fifteen subjects met criteria for probable AD as defined by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Diseases and Stroke/Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS/ADRDA).16 Forty-three subjects met the criteria for VaD established by the State of California Alzheimer's Disease and Treatment Centers (ADTC).17,18 Thirty-three subjects met the Lund-Manchester criteria19 for FTD as adopted by the Alzheimer's Research Centers of California of the California Department of Health Services.

The control subjects were 40 residents from a retirement community (Leisure World) in Southern California who did not have dementia. The control subjects' spouses were interviewed with the NPI, and the subjects themselves were evaluated with the MMSE on the same day. Inclusion criteria for the controls were a score of 25 or higher on the MMSE; completion of the NPI with information provided by control subjects' spouses; and no history of cognitive decline (as reported by the spouses) or complaints of memory abnormalities. The NPI was administered in the same way as it was with dementia patients and their caregivers.

NPI Assessment

The NPI was developed to assess psychopathology in patients with dementia,12,13 and, to that end, it elicits information from patients' caregivers. The NPI evaluates the frequency and severity of 10 neuropsychiatric disturbances during the previous 4 weeks: delusions, hallucinations, agitation, dysphoria, anxiety, apathy, irritability, euphoria, disinhibition, and aberrant motor behavior. Each of these traits receives a separate score for frequency (F) and severity (S) and a summary score, which is computed by multiplying the frequency and severity scores together (F×S). Frequency is scored on an ordinal scale from 1 to 4, and severity from 1 to 3. The F×S product is used as the final behavioral score for a given behavior. The NPI's interview questions are scripted, and all ratings are anchored. The NPI has demonstrated content validity, concurrent validity, convergent validity, interrater reliability, and test-retest reliability.12

The NPI evaluates several components of anxiety. The presence of anxiety is first queried by a general screening question about the patient's outward expression of anxiety (e.g., worry, tension, fear, or restlessness). If this question elicits a positive response, additional questions are asked to further define the nature of the complaint. The subquestions investigate additional components of anxiety, as specified by DSM-IV, including the outward expression of the experience of anxiety (e.g., expressions of worry or difficulty relaxing), awareness of physiological sensations (e.g., palpitations or shortness of breath), and avoidance of feared situations (e.g., riding in the car or being in crowds). An additional open-ended question asks about any other signs of anxiety the patient expresses or manifests.12

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute Biostatistical Core Service using SPSS statistical software. Between-group comparisons were performed with an analysis of variance (ANOVA) for normally distributed data or data that were transformed in order to meet a standard test of normality (Shapiro-Wilk test). A P value of 0.05 or less was accepted as significant. When significant F ratios from the ANOVA were obtained, multiple comparisons between group means were made using the post hoc Dunnett T3 multiple range test for groups with unequal variance. Age, age at onset of the disorder, and MMSE score were included as covariates in the above analyses where appropriate.

Group comparisons for dichotomous outcomes (i.e., presence or absence of anxiety) were made with the chi-square test of independence with Yates's correction. Post hoc multiple comparisons between group means were made with the continuity correction Pearson chi-square calculation. Partial correlations controlling for MMSE were obtained between different behavioral domain scores on the NPI and the FAQ scale.

RESULTS

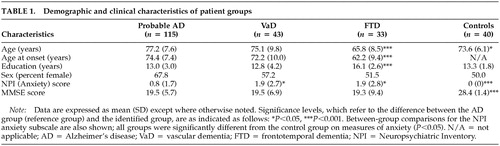

Study population.Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the study populations. The mean ± SD age of the control subjects (73.6 ± 6.1) was lower than that of patients with AD (77.2 ± 7.6; P<0.05) and higher than that of patients with FTD (65.8 ± 8.5; (P<0.001). The mean age of patients with FTD (65.8 ± 8.5) was lower than that of patients with AD (77.2 ± 7.6; P<0.001) or VaD (75.1 ± 9.8; P<0.001). These results are consistent with the earlier age at onset of FTD (under age 65).20

Of the patients with AD, 65.2% were white, non-Hispanic, 17.4% were black, non-Hispanic, 4.3% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 13.1% were classified as other. In the VaD group, 74.4% were white, non-Hispanic, 18.6% were black, non-Hispanic, 2.3% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 4.7% were other. In the FTD group, 84.8% were white, non-Hispanic, 9.0% were white, Hispanic, and 6% were other. All control subjects were white, non-Hispanic.

The mean MMSE score of the control group was higher than that of the dementia groups (AD, VaD, FTD; P<0.001); there were no significant differences among patient groups.

The FTD group differed from all others in total years of education; the FTD group was more highly educated (16.1 ± 2.6; P<0.001).

Frequency and Characteristics of Anxiety. Anxiety was reported less frequently in patients with AD than in those with VaD or FTD. Caregivers reported the presence of anxiety in 30 patients with probable AD (26.1%), 22 patients with VaD (51.2%), and 18 patients with FTD (54.5%). A significant difference between groups was noted (Pearson chi-square, χ2=36.4, P<0.001). Comparisons between groups demonstrated a significant difference in the presence of anxiety between the AD and VaD groups (Yates corrected chi-square, χ2 = 7.8, P<0.01) and between the AD and FTD groups (χ2 = 80.01).

The mean anxiety score of the AD group (0.8 ± 1.7) was significantly lower than that of the FTD group (1.9 ± 2.8; P<0.05) and the VaD group (1.9 ± 2.7; P<0.05) (see Table 1). All dementia groups had significantly higher scores than the control group (P<0.01). No significant differences were observed between the VaD and FTD groups. These comparisons remained statistically significant when analyses were adjusted for the covariates of age, age at onset of the disorder, educational level, and MMSE score.

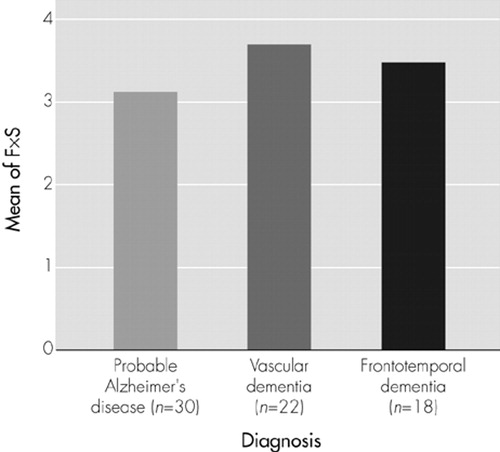

When we performed a subgroup analysis including only patients in whom anxiety was present (Figure 1), no significant differences in anxiety scores between groups were observed. Thus, the between-group differences delineated in Table 1 are due to differences in the prevalence of the report of anxiety among the various forms of dementia, not to differences in the level of anxiety reported in symptomatic patients in each group.

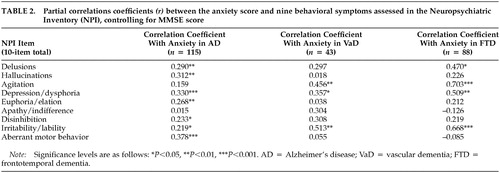

Association Between Other Comorbid Behavioral Traits and Anxiety. We calculated correlation coefficients between anxiety scores and other comorbid behavioral symptoms for the various groups. Table 2 shows partial correlations, controlling for MMSE score, between the anxiety score and each of the other behavioral traits for the three dementia groups. When associations were examined across all dementia groups, positive correlations were noted between anxiety and depression and between anxiety and irritability. Among patients with AD, anxiety also was associated with delusions, hallucinations, euphoria, disinhibition, and aberrant motor behavior. The association between anxiety and other behavioral features was more apparent among patients with AD than among those with FTD or VaD.

The association between anxiety and depression may be explained in part by the presence of an anxious depression in some patients, given that 19 of 30 (63.3%) AD patients with anxiety also had depression. In patients with FTD, 15 of 18 (83.3%) with anxiety had both anxiety and depression. In patients with VaD, 18 of 22 (81.8%) with anxiety had both anxiety and depression.

The presence of anxiety symptoms is not equivalent to establishing a diagnosis of anxiety disorder. Only one of 115 subjects with AD in this study had anxiety as the predominant major neuropsychiatric symptom and would meet DSM-IV criteria for anxiety disorder due to a general medical condition (namely, AD). However, 30% of the AD patients with anxiety had subscale scores of 4 or greater, which is generally considered to be clinically significant. Among patients with FTD and VaD, 38.9% and 45.5%, respectively, had anxiety scores of 4 or greater.

Disease Severity and Anxiety in AD. When MMSE scores for the AD group were divided into terciles indicating mild (24–29), moderate (15–23), and severe (<15) dementia, a one-way ANOVA revealed a significant linear relationship between severity level and anxiety score (F = 5.49, df = 1,111); patients with more severe dementia had higher anxiety scores (P<0.05). Rank correlation using Spearman's rho showed an inverse correlation between anxiety score and total MMSE score (ρ = –0.308, P<0.05), indicating that the degree of anxiety increases as mental status deteriorates with advancing disease.

Gender and Anxiety in AD. No significant differences in anxiety scores were observed between men and women with AD.

Ethnicity and Anxiety in AD. A one-way ANOVA showed no significant differences in anxiety scores among the different ethnic groups (P = 0.52). Given the small number of ethnic minority patients in the sample, however, the statistical power of this negative conclusion is limited.

Age at Onset and Anxiety in AD. In order to determine whether the age at onset of the disease influenced caregivers' reports of anxiety among patients with AD, subjects were divided into those whose onset occurred before age 65 or at age 65 or older. The mean anxiety score was higher for the group with the earlier onset (2.1 ± 3.1) than for the group with a later onset (0.7 ± 1.6). An ANOVA was performed on the group means, and a corrected model was applied to adjust for the covariates of the patient's current age and the total number of years since the onset of the disease. A statistically significant difference between the earlier and later onset categories was observed after application of the model (P<0.01; R2 = 0.1, adjusted R2 = 0.07). Thus, patients with a younger age at onset of AD had a higher level of anxiety. There was no significant correlation between age at evaluation and anxiety score (Spearman's rho correlation coefficient = 0.065, P = 0.49).

Instrumental Activities and Anxiety in AD. The FAQ scale assesses independence in instrumental activities of daily living.15 The relationship between FAQ score and anxiety score for patients with AD was examined. Partial correlation coefficients corrected for MMSE score were obtained between the anxiety score and the FAQ score. Significant partial correlation coefficients were obtained for the anxiety score (r = 0.20, P = 0.04). Partial correlation coefficients between the FAQ score and the anxiety score, corrected for age, remained significant (r = 0.30, P = 0.002). These results suggest that anxiety may contribute to disability in social functioning and to decreased independence. This result is independent of the effects of age and severity of dementia.

Medication and Levels of Anxiety in AD. There were no statistically significant differences between patients with and without anxiety with respect to use of cholinesterase inhibitors (e.g., tacrine or donepezil). No difference was observed in the presence or absence of anxiety among patients with AD when the use of anxiolytic, neuroleptic, antidepressant, or other psychotropic medications was examined. Only one of the 115 patients with AD was receiving anxiolytics at the time of evaluation. Nineteen percent of patients with AD and 13.3% of AD patients with anxiety were receiving antidepressants.

DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional analysis, we used an established neuropsychiatric instrument, the NPI, to assess caregiver-reported anxiety among patients with dementia and normal control subjects. Anxiety was more common among patients with AD, VaD, and FTD than among normal controls. Anxiety was reported less commonly for patients with AD than for those with VaD or FTD. Among patients for whom anxiety was reported, no significant differences in mean scores were found between the diagnostic groups. Anxiety was more common among AD patients in whom the onset of the disease was before age 65 than among those whose onset was at age 65 or older. Significant partial correlations, adjusted for MMSE score, were observed between anxiety and depression and irritability across all dementia groups. Clinically relevant levels of anxiety (subscale scores of 4 or greater) were noted in 30% of patients with AD, 38.9% of patients with FTD, and 45.5% of patients with VaD.

These data suggest that anxiety constitutes a significant problem for many patients with dementia. The differences in reported anxiety between the patients with AD and those with VaD and FTD were unexpected. One possible explanation relates to the putative neuroanatomic substrate of anxiety. Recent studies suggest involvement of the orbitofrontal cortex in the subjective perception of anxiety.21 Higher levels of reported anxiety in VaD and FTD may reflect greater involvement of the frontal lobes in these conditions. Similar disease-related differences in anxiety have been reported in the few published studies that examine this question.22–24

Some behavioral changes associated with AD may be related to the cholinergic deficits in the brains of AD patients, and these neuropsychiatric abnormalities may respond to cholinergic therapy.25 Although less is known about the effect of cholinesterase inhibitors on the neuropsychiatric symptoms of AD than about the cognitive effects, preliminary evidence suggests that these agents may reduce apathy, anxiety, hallucinations, disinhibition, and aberrant motor behavior.26 Donepezil has been reported to decrease anxiety in patients with moderate to severe AD.27 In this study we did not observe an association between anxiety and the use of cholinesterase inhibitors; this may have been because our data were derived from the initial patient evaluation, and only 30 of 115 patients with probable AD were using such medications at the time of assessment.

We found no associations between anxiety and the use of neuroleptics, antidepressants, or other psychotropic medications. Only one patient of the 30 patients identified as having anxiety in the AD group was receiving an anxiolytic medication at the time of evaluation. However, many physicians prescribe antidepressants for their anxiolytic properties, desiring to avoid the potential cognitive side effects of benzodiazepines. In our sample, 22 of 115 (19%) patients with AD were receiving antidepressants, although only four of the 30 (13.3%) identified as having anxiety were receiving an antidepressant. These data suggest that there may be a role for more aggressive treatment of anxiety symptoms that are distressing to the patient and caregivers.

Although this cross-sectional analysis suggests that anxiety is a frequent behavioral manifestation across different forms of dementia, several limitations of the study design should be noted. First, relative increases or decreases of anxiety from a baseline level—such as prior to the onset of dementia—may not be accurately measured by assessment of a single time point. Second, the presence of relatively few subjects in the VaD and FTD groups did not allow for subgroup analyses to discern the influence of potential covariates such as gender, ethnicity, and the association between anxiety and FAQ scores. Third, given the homogeneity of the study sample (largely white, well-educated, and upper middle class), any generalization of the findings to other populations must be made with caution. Fourth, patients with VaD have frequently been found to have both cerebrovascular disease and AD-type pathology at autopsy, and the VaD group in this study may include patients with mixed degenerative and vascular disease. Finally, the exclusion criteria for the study were based on caregivers' reports of medical conditions, which may not include all factors that could affect the presence of anxiety. This difficulty is inherent to all studies that use proxy respondents for assessment of disease states, and it is particularly relevant in studies of dementia.

In summary, anxiety is a common behavioral symptom in patients with AD, VaD, and FTD. Among patients with AD, anxiety is associated with distinctive patterns of other behavioral manifestations, and it is more severe among patients in whom the onset of the disorders occurs earlier in life. It is less common in AD than in VaD and FTD, and this may be due to anatomical variations among these disorders. Considering the low proportion of patients in our group receiving anxiolytic therapy at the initial evaluation for dementia, there may be the opportunity for more aggressive management of disabling symptoms and for continued research into the use of potentially multifaceted pharmacological agents such as cholinesterase inhibitors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by NIH grant AG-16570, by a grant from the Alzheimer's Disease Research Center of California, and by the UCLA Sidell-Kagan Foundation. The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Koren Hanson in database access.

|

|

FIGURE 1. Mean of anxiety scores for patients with anxiety, by dementia diagnosis. ANOVA demonstrated no significant differences among groups (F = 0.4, P = 0.6). F = frequency; S = severity; F×S = subscale score

1 Levy ML, Cummings JL, Kahn-Rose R: Neuropsychiatric symptoms and cholinergic therapy for Alzheimer's disease. Gerontology 1999; 45(suppl 1):15-22Google Scholar

2 Mega MS, Cummings JL, Fiorello T, et al: The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1996; 46:130-135Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Russo J, Vitaliano PP, Brewer DD, et al: Psychiatric disorders in spouse caregivers of care recipients with Alzheimer's disease and matched controls: a diathesis-stress model of psychopathology. J Abnorm Psychol 1995; 104:197-204Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Jost BC, Grossberg GT: The evolution of psychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: a natural history study [see comments]. J Am Geriatr Soc 1996; 44:1078-1081Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Harwood DG, Ownby RL, Barker WW, et al: The behavioral pathology in Alzheimer's disease scale (BEHAVE-AD): factor structure among community-dwelling Alzheimer's disease patients. Int J Geriat Psychiatry 1998; 13:793-800Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Mendez M, Martin RJ, Smyth KA, et al: Psychiatric symptoms associated with Alzheimer's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1990; 2:28-33Link, Google Scholar

7 Sultzer DL, Levin HS, Mahler ME, et al: Assessment of cognitive, psychiatric, and behavioral disturbances in patients with dementia: the neurobehavioral rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40:549-555Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Tariot PN, Mack JL, Patterson MB, et al: The behavior rating scale for dementia of the consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1349-1357Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Teri L, Truax P, Logsdon R, et al: Assessment of behavioral problems in dementia: the revised memory and behavior problems checklist. Psychol Aging 1992; 2:622-631Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Tractenberg RE, Patterson M, Weiner MF, et al: Prevalence of symptoms on the CERAD behavior rating scale for dementia in normal elderly subjects and Alzheimer's disease patients. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2000; 12:472-479Link, Google Scholar

11 Chemerinski E, Petracca G, Manes F, et al: Prevalence and correlates of anxiety in Alzheimer's disease. Depress Anxiety 1998; 7:166-170Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al: The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994; 44:2308-2314Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Cummings JL: The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: assessing psychopathology in dementia patients. Neurology 1997; 48:S10-S16Google Scholar

14 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189-198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH Jr: Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol 1982; 37:323-329Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al: Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group, Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology 1984; 34:939-944Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Romaan GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, et al: Vascular dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop. Neurology 1993; 43:250-260Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Chui HC, Victoroff JI, Margolin D, et al: Criteria for the diagnosis of ischemic vascular dementia proposed by the State of California Alzheimer's Disease Diagnostic and Treatment Centers. Neurology 1992; 42:473-480Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 The Lund and Manchester Groups: Clinical and neuropathological criteria for frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994; 57:416-418Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al: Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology 1998; 51:1546-1554Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Charney DS, Deutch A: A functional neuroanatomy of anxiety and fear: implications for the pathophysiology and treatment of anxiety disorders. Crit Rev Neurobiol 1996; 10:419-446Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Duara R, Barker W, Luis CA: Frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease: differential diagnosis. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1999; 10(suppl 1):37-42Google Scholar

23 Levy ML, Miller BL, Cummings JL, et al: Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal dementias: behavioral distinctions. Arch Neurol 1996; 53:687-690Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Mendez MF, Perryman KM, Miller BL, et al: Behavioral differences between frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease: a comparison on the BEHAVE-AD rating scale. Int Psychogeriatr 1998; 10:155-162Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Cummings JL: Cholinesterase inhibitors: a new class of psychotropic compounds. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:4-15Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Cummings JL, Back C: The cholinergic hypothesis of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 6:S64-S78Google Scholar

27 Feldman H, Gauthier S, Hecker J, et al: A 24-week, randomized, double-blind study of donepezil in moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 2001; 57:613-620Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar