Psychiatric Manifestations of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease: A 25-Year Analysis

Abstract

This study characterizes the type and timing of psychiatric manifestations in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD). Historically, sCJD has been characterized by prominent neurological symptoms, while the variant form (vCJD) is described as primarily psychiatric in presentation and course: A retrospective review of 126 sCJD patients evaluated at the Mayo Clinic from 1976–2001 was conducted. Cases were reviewed for symptoms of depression, anxiety, psychosis, behavior dyscontrol, sleep disturbances, and neurological signs during the disease course. Eighty percent of the cases demonstrated psychiatric symptoms within the first 100 days of illness, with 26% occurring at presentation. The most commonly reported symptoms in this population included sleep disturbances, psychotic symptoms, and depression. Psychiatric manifestations are an early and prominent feature of sporadic CJD, often occurring prior to formal diagnosis.

Initially described in 1921, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is a rare, transmissible prion disease of the brain.1 The unusual syndrome of sporadic CJD (sCJD) is characterized by a rapidly progressive dementia, often accompanied by myoclonus and other signs of central nervous system (CNS) dysfunction, ultimately leading to death. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and its various forms have received increased media attention due to concerns regarding bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) or mad cow disease, which has been found in U.S. and Canadian cattle populations. BSE has been linked to a new form of human CJD known as variant CJD (vCJD).2–4 The typical presentation and course of vCJD have been contrasted with sCJD, in that it normally strikes a younger age group and has been associated with more prominent psychiatric symptoms than the classically described sporadic form of CJD.

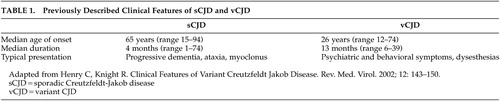

In 1996, the variant form of CJD, affecting a younger population and accompanied by early, striking neuropsychiatric manifestations, was described by Will et al. as having distinct clinical and neuropathological features5 (Table 1). The different clinical features of these syndromes continue to be highlighted by the ongoing surveillance data gathered from the National CJD Surveillance Unit in Edinburgh, Scotland, United Kingdom.6,7 According to its report, the early stages of vCJD are dominated by neuropsychiatric symptoms, which is in contrast to the classically described course of sCJD in which psychiatric manifestations are “rare” or “atypical.”8,9 Despite the continued attention to vCJD as a new and discrete entity, there are a number of case reports suggesting that psychiatric manifestations may occur as a feature of sCJD.10–22 This study explores the reported frequency, timing, and treatment of psychiatric symptoms during the disease course of sporadic CJD.

METHOD

Subjects

This study was an IRB-approved retrospective medical record review of all patients (237) diagnosed with CJD as found in the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota record system, between the years 1976 and 2001. This record system includes inpatient, outpatient and outreach records as well as surgical and pathology notes. The subjects were identified using encoded diagnoses of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease, spongiform encephalopathy, Jakob’s disease, and prion disease.

Inclusion Criteria

The criteria used for inclusion of patients as positive for CJD were taken from those of Aksamit and Chung,10 which were modified by Masters et al.23 Only those patients meeting the criteria for definite or probable CJD were included in the review. Definite cases were identified neuropathologically, either by autopsy or biopsy. Probable cases were defined as patients without tissue verification but who had diagnostic electroencephalogram (EEG) changes, dementia, and at least one other clinical finding compatible with CJD. Diagnostic EEG findings were defined as periodic sharp waves. The other clinical findings included myoclonus, extrapyramidal symptoms, ataxia and cortical blindness or focal cortical syndromes.

Exclusion Criteria

Individuals were excluded if they did not consent to have their records reviewed for research purposes, were less than 18 years of age, or did not have adequate documentation to meet criteria for definite or probable CJD. Individuals with possible CJD were excluded. Possible cases often had dementia and/or myoclonus, with or without ataxia, extrapyramidal features, or cortical syndromes compatible with CJD. EEG findings were nonspecific or normal. No neuropathological verification was available in any of the excluded possible cases.

Data Collection

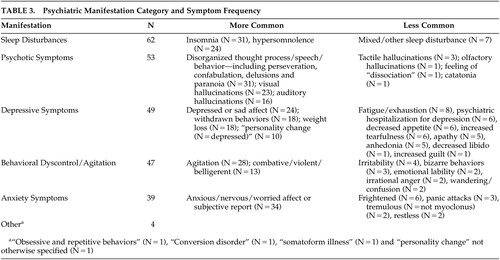

Each subject included in this study had their medical record comprehensively reviewed, including all clinical notes, laboratory and imaging findings, and general correspondence that had been included as a part of the record. Psychiatric symptom timing and type during the disease course were carefully recorded, along with medications used and documented outcomes. Due to the retrospective and chart review nature of this study, it was not possible to use a formal, objective neuropsychiatric assessment. However, when neuropsychiatric symptoms were noted, they were categorized as psychotic symptoms, depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, behavioral dyscontrol/agitation, sleep disturbances, or other. Table 3 lists the psychiatric symptom categories and symptom frequency. The categorization and timing of symptoms were based entirely on the available notes as documented by the treating teams and family members, including physicians, medical students, nurses and social workers, along with compiled laboratory and imaging data. Verbatim quotes representing the symptom, along with the specific dates (when available), were documented in each case.

In addition to categorization of the observed manifestation, treatments offered to the patients during the course of illness were documented. The treatment outcomes were noted to be positive, negative, or neutral. If there was no comment on clinical change, the treatment was categorized as having neutral effect. The data were collected using a three-point scale for each class of medication used: 1 = negative effect; 2 = neutral effect, 3 = positive effect. The medications were classified as anxiolytics/hypnotics, anticonvulsants/mood stabilizers, antidepressants, antipsychotics, or other treatment interventions where noted.

Further clinical information was gathered to include date of CJD symptom onset as defined by the clinical documentation, eventual date of CJD diagnosis, date of death, and whether there was a family history positive for CJD. Patients’ clinical charts were also reviewed for evidence of a past psychiatric and neurological history. Neurological symptoms (date of onset and type) during disease course and presenting symptoms (date of onset and type) were recorded in each case. Prodromal or presenting symptoms were defined as the clinical signs and symptoms that led the patient to seek medical attention and were retrospectively recognized as the initial manifestations of the disease course. Imaging studies, including computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), interpretation and EEGs were reviewed and recorded. Neuron Specific Enolase (NSE) and 14–3–3 assays in the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) were recorded when available. Both measures are CSF markers that have been described as a useful adjunct to confirm the diagnosis CJD.24 Demographic information regarding each patient’s date of birth, sex, occupation, and place of residence was also included.

RESULTS

Subjects

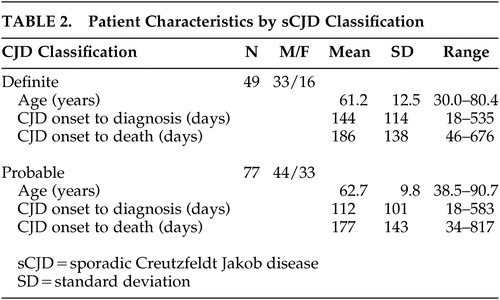

Of the initial 237 cases identified through the initial database query, 126 met criteria for either definite (N=49) or probable (N=77) CJD. No case of vCJD was identified in this sample. Nine of the cases included in the review had family histories positive for CJD. The patient characteristics of the definite and probable classifications appeared relatively consistent (Table 2). The mean age of both populations was nearly 62 years, with a range of 30.0 to 90.7. No statistically significant differences in baseline demographic measures or clinical manifestations were observed between the definite and probable CJD groups. In both populations, there were more men than women. The average onset to diagnosis in both populations was nearly 4 months and onset to death was approximately 6 months. These findings are similar to previously reported sCJD populations.8,9,12

Psychiatric Manifestations

In this population, 116/126 (92%) patients were categorized as having at least one psychiatric manifestation during the course of illness. If sleep disturbances were not included, the total among this population was 112/126 (89%). Most cases had more than one symptom category noted during the course of illness (Table 3).

Timing of Psychiatric Manifestations

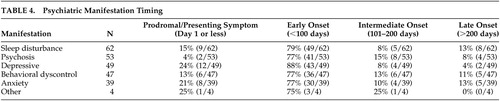

Symptom onset and timing were determined by noting the documented date of the first symptoms observed as reported by the physician. A psychiatric manifestation in the prodromal or presenting phase of the illness was noted in 33/126 (26%) of the cases (Table 4). In six of these cases, more than one category was applied. Of the 116 cases that were classified as having at least one psychiatric manifestation, 101 (86%) had the first symptom within 100 days of CJD onset. This result implies that the majority of the cases were demonstrating psychiatric manifestations of CJD prior to formal diagnosis.

The majority of the cases presented initially to a primary care physician (internist or family physician). In nine of the cases, a psychiatrist initially evaluated the patient. During the course of illness, 83 cases received inpatient care, 6 of which were treated at some point in a psychiatric hospital. Eventually, a neurologist evaluated every case in this series. As shown in Table 2, 3 to 4 months elapsed between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis. There was an average time of 2 months from the eventual date of diagnosis to death. On average, a patient suffered from undiagnosed CJD, usually with behavioral/psychiatric symptoms, for approximately 4 of the 6 months of the typical disease course.

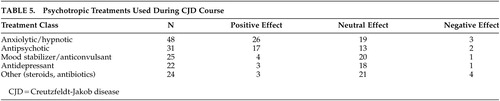

Medication

Medication use varied in terms of medication type, dosing strength, and length of medication trial but generally corresponded to the documented psychiatric symptoms. For example, when a patient was treated with a hypnotic or anxiolytic, there was usually supporting evidence for insomnia or anxiety-related symptoms. The medications most often associated with benefits, in the opinion of the treatment teams, included anxiolytic class medications and antipsychotic medications (Table 5). The choice of medication and dosing ranges varied significantly from year to year and case to case. The benefits observed from medications in the anxiolytic class may be due to their relatively rapid onset as well as the sedative and anticonvulsant effects. Benzodiazepine medication, most commonly lorazepam, was relatively successful when the patient exhibited myoclonus, sleep disruption, agitation, and symptoms consistent with anxiety.

Antipsychotic class medications were utilized with fair success in cases of hallucinatory phenomena and behavioral dyscontrol/agitation. There were two dystonic reactions when conventional antipsychotics were used. In both cases, the symptoms relented upon discontinuation of the agent.

Antidepressant and anticonvulsant/mood stabilizer class medications did not appear to provide consistent psychiatric symptom relief, although these were tried in nearly one-half of the cases. Although patients may not have received total symptom relief with the above-mentioned treatments, there were no recorded reports of hastened deterioration with treatment.

DISCUSSION

Until recently, it was believed that sCJD presented primarily with neurological symptoms. Our case series, however, demonstrates that psychiatric symptoms frequently occur in sCJD at diagnosis and during the early phase of this neurodegenerative disorder. Psychiatric symptoms are common occurrences in degenerative/demyelinating brain disorders.25,26 According to our data, sCJD should not be any different from other neurological disorders in this respect. Clinicians must therefore include sCJD in their differential diagnoses of new onset dementia, particularly when associated psychosis, sleep problems, and depression symptoms persist and worsen, despite standard psychiatric treatments.

Sleep Disturbances During CJD Course

Nearly one-half of the patients in this sample (62/126) were affected by sleep disturbances, ranging from profound hypersomnolence to insomnia. Seventy-nine percent (49/62) of the sleep disturbances occurred within the first 100 days following disease onset (Table 4). Insomnia was more likely to occur than hypersomnolence. The use of benzodiazepine/hypnotic class medications was useful in sleep restoration in cases of insomnia. Nine patients reported a sleep disturbance at presentation. Progressive dementing illnesses such as Lewy body dementia, AD, fatal familial insomnia, and Pick’s disease have also been associated with sleep disturbances.27–31 Sleep disturbance was found in a case report of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in a patient with thalamic involvement.32 Further clinical correlation with neuroimaging and neuropathology findings may be pertinent in understanding the basis of sleep disruption in this series of patients.

Psychotic Symptoms During CJD Course

We found psychotic symptoms in 42% of our patients (53/126). This percentage is similar to findings of hallucinations and delusions in patients with more common dementing illnesses such as AD and multi-infarct dementia.33 Although a mechanism for the psychotic symptoms in AD has not yet been delineated, an association with a dopamine receptor variation (DRD1) has been postulated.34 Lewy body dementia has been associated with visual hallucinations that are typically well formed, along with rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder.35 The CJD patients in our review showed a diffuse range of hallucinatory and delusional phenomena, ranging from paranoid and persecutory delusions to vivid and interactive visual and auditory hallucinations. Among the CJD cases with psychotic symptoms in this study, 77% (41/53) occurred within the first 100 days of illness onset, and only 4% (2/53) occurred as the presenting feature.

Depression During CJD Course

Sad or depressed affect during the course of illness in this CJD population was frequently reported by both the patients and their caregivers. Many of the patients tended to withdraw and become isolated within their care settings, even during the early stages of illness. Patients frequently demonstrated poor appetite and weight loss during the disease course. Weight loss early in the course of illness seemed more related to neurovegetative symptoms of depression, compared to later in the course when impaired motor mechanisms of deglutition occurred. Tearfulness, anhedonia, and complaints of exhaustion also occurred in several of the cases, typically within the first 100 days of illness. Six of the patients were hospitalized on a psychiatric inpatient unit for treatment of depression before the diagnosis of CJD was made. Antidepressant medication administration was documented in 22 of the cases, with only one case documented as having benefit. In one case, ECT was utilized as a treatment for the pre-CJD diagnosis of major depressive disorder with psychotic features. This patient showed modest and temporary improvement in the depressive symptoms.

Anxiety During the CJD Course

Anxiety and nervousness were symptoms frequently mentioned by the patients and their caregivers. Patients were often observed as anxious and fearful for no reason apparent from the environment. Two patients specifically mentioned their concerns over the deterioration of their memory and health prior to the severe dementia phase of illness. However, the appearance of nervousness and anxiety persisted for some patients beyond the time of cognitive collapse. Anxiolytic class medications appeared to be underemployed in these patients unless there was agitation and behavioral dyscontrol associated with the anxiety.

Behavioral Dyscontrol and Agitation During CJD Course

A significant number (47/126) of patients showed evidence of agitated and aggressive behavior. This finding is similar to reports of agitation and aggression in populations studied with other types of dementia.36 Many of the cases in which aggressive and agitated behavior occurred showed simultaneous hallucinations and sleep disturbances. The severity of agitation was difficult to ascertain from the record; however, these symptoms frequently led to hospital readmission when they occurred in the home or nursing facility settings. Furthermore, this group of patients was more likely to receive antipsychotic and anxiolytic class medication trials, with some reported benefit.

Limitations

Due to the retrospective nature of this study, detailed data on psychiatric and social factors were often limited. Retrospective interpretation of the medication effects may have biased the data, but the effects were classified based on the care provider’s documented comments. Follow-up data, including date of death and clinical course after being dismissed from local care facilities, were frequently absent. The relatively strict inclusion criteria for diagnosis as probable CJD may have excluded several cases. Specifically, EEG findings that were nondiagnostic or atypical for CJD, without tissue verification, excluded a patient from this study. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease can and does occur without the classic EEG findings. However, criteria for this study were established to provide a consistent and accurate retrospective diagnosis of CJD.

CONCLUSIONS

Historically, psychiatric manifestations have been described as a relatively infrequent occurrence in the sporadic form of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. However, our findings suggest otherwise. In this study, a vast majority of the cases were noted to have at least one psychiatric symptom during the course of illness, with nearly one-quarter occurring in the prodromal or presenting phase of the illness. After comparing the frequency of neuropsychiatric symptoms in sporadic CJD to studies describing the variant form of CJD, we found that there are fewer clinical differences than previously reported.5–7 While the age of patients with vCJD presentation is significantly younger and the course of illness is longer, the type and timing of psychiatric manifestations appear similar between these two diseases.

Although there is no currently known treatment for CJD, the quality of life for the patient and caregivers may be improved with symptomatic treatment of neuropsychiatric manifestations. Consequently, close observation and early intervention may improve the quality of care for those with this lethal and terrifying disease.

|

|

|

|

|

1 Jakob A: Uber eine der multiplen sklerose klinisch nahanstehende erkrankung des zentralnerven-systems (spastiche pseudosklerose) mit bemerkswertem anatomischen befunde. Medizenische Klinik 1921; 13:372–376Google Scholar

2 Thomas C: How now, mad cow? Time 2004; 163:46–49Medline, Google Scholar

3 Donnelly C: Bovine spongiform encephalopathy in the United States—an epidemiologist’s view. N Engl J Med 2004; 350:539–542Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Bruce M, Will R, Ironside J, et al: Transmissions to mice indicate that “new variant” CJD is caused by the BSE agent. Nature 1997; 389:498–501Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Will R, Ironside J, Zeidler M, et al: A new variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in the UK. Lancet 1996; 347:921–925Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Henry C, Knight R: Clinical features of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Rev Med Virol 2002; 12:143–150Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Spencer M, Knight R, Will R: First hundred cases of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: retrospective case note review of early psychiatric and neurological features. BMJ 2002; 324:1479–1482Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Brown P, Cathala F, Castaigne P, et al: Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: clinical analysis of a consecutive series of 230 neuropathologically verified cases. Ann Neurol 1986; 20:597–602Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Will R, Matthews W, Smith P, et al: A retrospective study of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in England and Wales 1970-1979, II: epidemiology. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1986; 49:749–755Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Aksamit A, Chung K: Trends in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease 1976-1996: the Mayo Clinic experience. J Neurol Sci 1997; 150(suppl):S72Google Scholar

11 Keshavan M, Lishman W, Hughes J: Psychiatric presentation of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: a case report. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 151:260–263Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Brown P, Cathala F, Sadowsky D, et al: Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in France, II: clinical characteristics of 124 consecutive verified cases during the decade 1968-1977. Ann Neurol 1979; 6:430–437Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Stevens E, Lament R: Psychiatric presentation of Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease. J Clin Psychiatry 1979; 40:445–446Medline, Google Scholar

14 Azorin J, Donnet A, Dassa D, et al: Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease misdiagnosed as depressive pseudodementia. Compr Psychiatry 1993; 34:42–44Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Yen C, Lin R, Liu C, et al: The psychiatric manifestation of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 1997; 13:263–267Medline, Google Scholar

16 Kozubski W, Wender M, Szczech J, et al: Atypical case of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) in a young adult. Folia Neuropathol 1998; 36:225–228Medline, Google Scholar

17 Costa C, Brucher J, Laterre C: Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. A clinico-neuropathological analysis of nine definite cases. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 1998; 56:356–365Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Moellentine C, Rummans T: The varied neuropsychiatric presentations of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Psychosomatics 1999; 40:260–263Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Jiang T, Moses H, Gordon H, et al: Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease presenting as major depression. South Med J 1999; 92:807–808Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Dunn N, Alfonso C, Young R, et al: Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease appearing as paranoid psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:2016–2017Medline, Google Scholar

21 Stone J, Zeidler M, Sharpe M: Misdiagnosis of conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:391Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Martindale J, Geschwind M, De Armond S, et al: Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease mimicking variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Arch Neurol 2003; 60:767–770Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Masters C, Harris J, Gajdusek D, et al: Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: patterns of worldwide occurrence and the significance of familial and sporadic clustering. Ann Neurol 1979; 5:177–188Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Aksamit AJ, Preissner C, Homburger H: Quantitation of 14-3-3 and neuron-specific enolase proteins in CSF in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurology 2001; 57:728–730Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Finkel S, Costa e Silva J, Cohen G, et al: Behavioral and psychological signs and symptoms of dementia: a consensus statement on current knowledge and implications for research and treatment. Int Psychogeriatr 1996; 8(suppl 3):497-500Google Scholar

26 Rabins P, Blacker D, Cohen E, et al: Practice guidelines for treatment of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias of late life. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154(suppl):1-39Google Scholar

27 Cibula J, Eisenschenk S, Gold M, et al: Progressive dementia and hypersomnolence with dream-enacting behavior: oneiric dementia. Arch Neurol 2002; 59:630–634Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 McKeith I, Perry E, Perry R: Report of the second dementia with Lewy body international workshop: diagnosis and treatment. consortium on dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurol 1999; 53:902–905Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 McCurry S, Logsdon R, Teri L, et al: Characteristics of sleep disturbance in community-dwelling Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1999; 12:53–59Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Fink J, Filling-Katz M, Sokol J, et al: Clinical spectrum of Niemann-Pick disease type C. Neurology 1989; 39:1040–1049Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Chapman J, Arlazoroff A, Goldfarb L, et al: Fatal insomnia in a case of familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease with the codon 200(Lys) mutation. Neurology 1996; 46:758–761Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 Taratuto A, Piccardo P, Reich E, et al: Insomnia associated with thalamic involvement in E200K Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurology 2002; 58:362–367Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 Cummings J, Miller B, Hill M, Neshkes R: Neuropsychiatric aspects of multi-infarct dementia and dementia of the Alzheimer type. Arch Neurol 1987; 44:389–393Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 Holmes C, Smith H, Ganderton R, et al: Psychosis and aggression in Alzheimer’s disease: the effect of dopamine receptor gene variation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001; 71:777–779Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 Rahkonen T, Eloniemi-Sulkava U, Rissanen S, et al: Dementia with Lewy bodies according to the consensus criteria in a general population aged 75 years or older. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003; 74:720–724Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36 Lyketsos C, Lopez O, Jones B, et al: Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. JAMA 2002; 288:1475–1483Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar