The Differential Diagnosis of Childhood- and Young Adult-Onset Disorders That Include Psychosis

METHODS

We conducted a literature search for disorders that may present with psychosis, utilizing PubMed and Ovid, with search terms including “psychosis” paired with “metabolic,” “genetic,” “congenital,” and “neurodevelopmental.” All disorders described in case reports or case series and literature reviews, including their references, were initially included. Disorders were then excluded if fewer than three published case reports with adequately described psychotic symptoms could be identified, or if due to nonheritable or noncongenital disorders. Descriptors of psychotic symptoms included such terms as “hallucinations,” “delusions,” “schizophrenia-like,” and “schizophreniform,” as well as known psychotic syndromes such as “Capgras syndrome.” To focus the review on disorders that could present in the typical age range for major axis I psychotic disorders, disorders that typically present beyond age 50 were excluded. Standard neurology and neuropsychiatric textbooks were consulted for additional information about the included disorders. 5 – 9

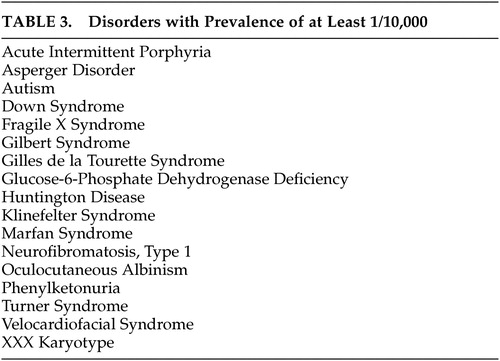

Disorders were categorized by the presence of one or more of 20 prominent groups of associated signs with an emphasis on those of major neurological significance. Group assignment was limited to those associated signs judged to occur commonly in each disorder. Disorders with unique phenotypic features that can be recognized easily were identified. Epidemiological information was gathered via OMIM, 10 GENETests, 11 and Orphanet 12 and disorders were classified by prevalence into three groups: more common (prevalence >1/10,000), rare (prevalence 1/10,000–1/50,000) and extremely rare (prevalence <1/50,000).

RESULTS

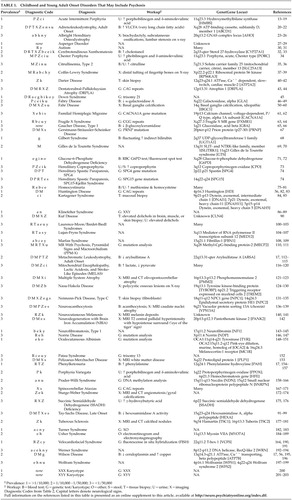

We identified 62 congenital disorders that may present from childhood through middle-age and include psychosis ( Table 1 ). Prominent associated neurological and physical sign groups are listed in Table 2 . Forty-four disorders (71%) have prominent associated neurological features that facilitate differential diagnosis. Seventeen disorders (27%) have readily recognizable unique phenotypes. Forty-five disorders (73%) may present without mental retardation. Fifty-three disorders (86%) have characteristic laboratory features. Fifty-three disorders (86%) have known genetic loci or several different etiologies with known loci (e.g., autism), and three disorders (5%) have loci yet unknown. Five disorders (8%) were due to chromosomal nondisjunction. Sixteen disorders (26%) have estimated prevalence of 1/10,000 or greater ( Table 3 ).

|

|

|

DISCUSSION

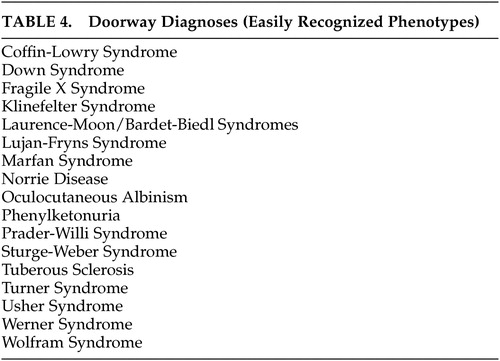

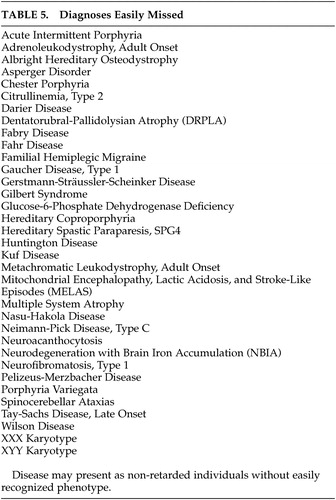

A neuropsychiatric diagnostic approach that takes relative prevalence into account is suggested to simplify a differential diagnosis that includes a large number of rare disorders. The diagnosis of unusual disorders that can present with psychosis receives little if any attention in psychiatry or neurology residency training. Although most of these disorders are unlikely to present to psychiatrists or neurologists more than occasionally, the failure of physicians to recognize them may lead to unnecessary delay in diagnosis, misdiagnosis, or missed opportunities to offer genetic counseling. Furthermore, failure to recommend appropriate treatment or application of inappropriate treatment may lead to adverse outcomes. A substantial minority of these disorders have prominent unique phenotypes that are readily recognizable at a distance, which we have called “doorway diagnoses.” These are listed in Table 4 . Fifty-five percent of disorders identified have subtypes that present without mental retardation or easily recognized phenotypes and are thus easily missed ( Table 5 ).

|

|

It would be cost-prohibitive to order a laboratory and neurodiagnostic workup to rule out all of the possible causes of psychotic symptoms, even if that workup were reserved only for those disorders whose natural history is atypical for major axis I psychotic disorders. A coherent neuropsychiatric approach, such as the one presented here, improves cost management by providing a probability-guided, examination-based approach to focus the diagnostic workup.

Identification by literature review of disorders that have been reported to include psychotic symptoms is a first step and may be diagnostically useful, but presents a number of confounding variables that should be addressed. With the exception of the more common disorders, it would be difficult to assemble large enough populations with a given diagnosis over sufficient time to carefully study their psychotic symptoms. Whether the psychotic symptoms are directly caused by the disorder, are a common behavioral response to environmental or medical stress, or are merely coincidental cannot be determined from these reports. Despite the inclusion of misleading terms such as “schizophreniform,” “schizophrenia-like,” or “manic” in many case reports, the histories of many of the reported disorders do not appear to be consistent with axis I disorders such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar mania, or major depression with psychotic features, despite phenotypic similarity at the time of presentation. Few congenital disorders have been described that closely resemble schizophrenia. Metachromatic leukodystrophy, which has both negative and positive signs and symptoms and may begin within the typical age range of schizophrenia onset, is one such disorder. Velocardiofacial syndrome, which typically progresses from mood disorder to schizophrenia-like disorder and may account for up to 6% of childhood-onset schizophrenia, is another.

Another potential limitation of this review arises from reliance upon the most common presentations to determine the major associated neuropsychiatric signs. For example, although neurofibromatosis type 1 certainly may be a cause of seizures, seizures are estimated to occur only in 7% of affected individuals; therefore, neurofibromatosis type 1 was not included in the seizure group.

Studying neuropsychiatric disorders of known etiology that include psychosis may ultimately lead to research aimed at understanding the etiology of psychotic symptoms in axis I disorders. With recent improvements in DNA analysis, genes have been identified for the majority of these disorders, many of which are causative for the disorder and not merely associated with one subtype or susceptible population. As genotyping becomes less cost-prohibitive and more commonly available, neuropsychiatrists will need to develop increased sophistication with the utilization of genetic tests in the differential diagnosis of psychosis.

CONCLUSION

As consultants frequently called upon to evaluate atypical presentations of psychosis, neuropsychiatrists should be aware of congenital disorders that can present with psychosis, however rarely. To minimize missed diagnoses, both general psychiatrists and neuropsychiatrists should become familiar with the phenotypes of the 17 “doorway diagnoses” we have listed ( Table 4 ). We recommend a differential diagnostic approach based on estimated prevalence of the disorders and their most prominent associated neuropsychiatric and physical features, to facilitate appropriate diagnosis in a systematic and cost-effective fashion.

1 . Davison K: Schizophrenia-like psychoses associated with organic cerebral disorders: a review. Psychiatr Dev 1983; 1:1–33Google Scholar

2 . Gray RG, Preece MA, Green SH, et al: Inborn errors of metabolism as a cause of neurological disease in adults: an approach to investigation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000; 69:5–12Google Scholar

3 . Sedel F, Baumann N, Turpin J-C, et al: Psychiatric manifestations revealing inborn errors of metabolism in adolescents and adults. J Inherit Metab Dis 2007; 30:631–641Google Scholar

4 . Walterfang M, Wood SJ, Velakoulis D, et al: Diseases of white matter and schizophrenia-like psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2005; 39:746–756Google Scholar

5 . Menkes J, Sarnat H, Maria B: Child Neurology, 7th ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott, 2006Google Scholar

6 . Nyhan WL, Barshop BA, Ozand PT (eds): Atlas of Metabolic Diseases, 2nd ed. London, Hodder Arnold, 2005Google Scholar

7 . Ropper AH, Brown RH: Adams and Victor’s Principles of Neurology, 8th ed. New York, McGraw-Hill, 2005Google Scholar

8 . Rosenberg R, Prusiner S, DiMauro S, et al: The Molecular and Genetic Basis of Neurologic and Psychiatric Disease. Oxford, Butterworth Heinemann, 2003Google Scholar

9 . Rowland L: Merritt’s Neurology, 11th ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott, 2005Google Scholar

10 . McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM). Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/Google Scholar

11 . University of Washington, Seattle: GeneTests: Medical Genetics Information Resource (database online), 1993–2008. Available at http://www.genetests.orgGoogle Scholar

12 . INSERM: Orphanet: an online database of rare diseases and orphan drugs. 1997. Available at http://www.orpha.netGoogle Scholar

13 . Bazakis AM, Kunzler C: Altered mental status due to metabolic or endocrine disorders. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2005; 23:901–908, x–xiGoogle Scholar

14 . Chinnery PF, Cartlidge NE, Burn DJ, et al: Management of parkinsonism and psychotic depression in a case of acute intermittent porphyria. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997; 62:542Google Scholar

15 . Croarkin P: From King George to neuroglobin: the psychiatric aspects of acute intermittent porphyria. J Psychiatr Prac 2002; 8:398–405Google Scholar

16 . Ellencweig N, Schoenfeld N, Zemishlany Z: Acute intermittent porphyria: psychosis as the only clinical manifestation. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 2006; 43:52–56Google Scholar

17 . Estrov Y, Scaglia F, Bodamer OA: Psychiatric symptoms of inherited metabolic disease. J Inherit Metab Dis 2000; 23:2–6Google Scholar

18 . Massey EW: Neuropsychiatric manifestations of porphyria. J Clin Psychiatry 1980; 41:208–213Google Scholar

19 . Pepplinkhuizen L, Bruinvels J, Blom W, et al: Schizophrenia-like psychosis caused by a metabolic disorder. Lancet 1980; 1:454–456Google Scholar

20 . Garside S, Rosebush PI, Levinson AJ, et al: Late-onset adrenoleukodystrophy associated with long-standing psychiatric symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:460–468Google Scholar

21 . Kopala LC, Tan S, Shea C, et al: Adrenoleukodystrophy associated with psychosis. Schizophr Res 2000; 45:263–265Google Scholar

22 . Rosebush PI, Garside S, Levinson AJ, et al: The neuropsychiatry of adult-onset adrenoleukodystrophy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1999; 11:315–327Google Scholar

23 . Hay GG, Jolley DJ, Jones RG: A case of the Capgras syndrome in association with pseudo-hypoparathyroidism. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1974; 50:73–77Google Scholar

24 . Levine MA: Clinical spectrum and pathogenesis of pseudohypoparathyroidism. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2000; 1:265–274Google Scholar

25 . Nakamura Y, Matsumoto T, Tamakoshi A, et al: Prevalence of idiopathic hypoparathyroidism and pseudohypoparathyroidism in Japan. J Epidemiol 2000; 10:29–33Google Scholar

26 . Preskorn SH, Reveley A: Pseudohypoparathyroidism and Capgras syndrome. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:34–37Google Scholar

27 . Fombonne E: What is the prevalence of Asperger disorder? J Autism Dev Disord 2001; 31:363–364Google Scholar

28 . Raja M, Azzoni A: Asperger’s disorder in the emergency psychiatric setting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2001; 23:285–293Google Scholar

29 . Ryan RM: Treatment-resistant chronic mental illness: is it Asperger’s syndrome? Hosp Community Psychiatry 1992; 43:807–811Google Scholar

30 . Dhossche DM: Autism as early expression of catatonia. Med Sci Monit 2004; 10:RA31–39Google Scholar

31 . Simashkova NV: Psychotic forms of atypical autism in children. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova 2006; 106:17–26Google Scholar

32 . Berginer VM, Foster NL, Sadowsky M, et al: Psychiatric disorders in patients with cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:354–357Google Scholar

33 . Gallus GN, Dotti MT, Federico A: Clinical and molecular diagnosis of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis with a review of the mutations in the CYP27A1 gene. Neurol Sci 2006; 27:143–149Google Scholar

34 . Qadiri MR, Church SE, McColl KE, et al: Chester porphyria: a clinical study of a new form of acute porphyria. Br Med J 1986; 292:455–459Google Scholar

35 . Maruyama H, Ogawa M, Nishio T, et al: Citrullinemia type II in a 64-year-old man with fluctuating serum citrulline levels. J Neurol Sci 2001; 182:167–170Google Scholar

36 . Saheki T, Kobayashi K: Mitochondrial aspartate glutamate carrier (citrin) deficiency as the cause of adult-onset type II citrullinemia (CTLN2) and idiopathic neonatal hepatitis (NICCD). J Hum Genet 2002; 47:333–341Google Scholar

37 . Collacott RA, Warrington JS, Young ID: Coffin-Lowry syndrome and schizophrenia: a family report. J Ment Defic Res 1987; 31:199–207Google Scholar

38 . Haspeslagh M, Fryns JP, Beusen L, et al: The Coffin-Lowry syndrome: a study of two new index patients and their families. Eur J Pediat 1984; 143:82–86Google Scholar

39 . Sivagamasundari U, Fernando H, Jardine P, et al: The association between Coffin-Lowry syndrome and psychosis: a family study. J Intellect Disabil Res 1994; 38:469–473Google Scholar

40 . Hellwig B, Hesslinger B, Walden J: Darier’s disease and psychosis. Psychiatry Res 1996; 64:205–207Google Scholar

41 . Lange CL: Psychosis only skin deep. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:2055Google Scholar

42 . Wojas-Pelc A, Setkowicz M, Pelc J: Familial Darier disease and mental retardation in mother and her two sons. Przeglad Lekarski 2002; 59:946–949Google Scholar

43 . Adachi N, Arima K, Asada T, et al: Dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA) presenting with psychosis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001; 13:258–260Google Scholar

44 . Potter NT, Meyer MA, Zimmerman AW, et al: Molecular and clinical findings in a family with dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy. Ann Neurol 1995; 37:273–277Google Scholar

45 . Hurley AD: The misdiagnosis of hallucinations and delusions in persons with mental retardation: a neurodevelopmental perspective. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry 1996; 1:122–133Google Scholar

46 . Liston EH, Levine MD, Philippart, M: Psychosis in Fabry disease and treatment with phenoxybenzamine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1973; 29:402–403Google Scholar

47 . MacDermot KD, Holmes A, Miners AH: Anderson-Fabry disease: clinical manifestations and impact of disease in a cohort of 98 hemizygous males. J Med Genet 2001; 38:750–760Google Scholar

48 . Shen YC, Haw-Ming L, Lin CC, et al: Psychosis in a patient with Fabry’s disease and treatment with aripiprazole. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2007; 31:779–780Google Scholar

49 . Vargas-Díez E, Chabás A, Coll MJ, et al: Angiokeratoma corporis diffusum in a Spanish patient with aspartylglucosaminuria. Br J Dermatology 2002; 147:760–764Google Scholar

50 . Chabot B, Roulland C, Dollfus S: Schizophrenia and familial idiopathic basal ganglia calcification: a case report. Psychol Med 2001; 31:741–747Google Scholar

51 . Cummings JL, Gosenfeld LF, Houlihan JP, et al: Neuropsychiatric disturbances associated with idiopathic calcification of the basal ganglia. Biol Psychiatry 1983; 18:591–601Google Scholar

52 . Flint J, Goldstein LH: Familial calcification of the basal ganglia: a case report and review of the literature. Psychol Med 1992; 22:581–595Google Scholar

53 . Francis AF: Familial basal ganglia calcification and schizophreniform psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 135:360–362Google Scholar

54 . Geschwind DH, Loginov M, Stern JM: Identification of a locus on chromosome 14q for idiopathic basal ganglia calcification (Fahr disease). Am J Hum Genet 1999; 65:764–772Google Scholar

55 . Jakab I: Basal ganglia calcification and psychosis in mongolism. Eur Neurol 1978; 17:300–314Google Scholar

56 . Lauterbach EC, Cummings JL, Duffy J, et al: Neuropsychiatric correlates and treatment of lenticulostriatal diseases: a review of the literature and overview of research opportunities in Huntington's, Wilson's, and Fahr's diseases. A report of the ANPA Committee on Research. American Neuropsychiatric Association. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 10:249–266Google Scholar

57 . Lauterbach EC, Spears TE, Prewett MJ, et al: Neuropsychiatric disorders, myoclonus, and dystonia in calcification of basal ganglia pathways. Biol Psychiatry 1994; 35:345–351Google Scholar

58 . Oliveira JR, Spiteri E, Sobrido MJ, et al: Genetic heterogeneity in familial idiopathic basal ganglia calcification (Fahr disease). Neurology 2004; 63:2165–2167Google Scholar

59 . Ostling S, Andreasson LA, Skoog I: Basal ganglia calcification and psychotic symptoms in the very old. Int J Geriat Psychiatry 2003; 18:983–987Google Scholar

60 . Shouyama M, Kitabata Y, Kaku T, et al: Evaluation of regional cerebral blood flow in Fahr disease with schizophrenia-like psychosis: a case report. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005; 26:2527–2529Google Scholar

61 . Feely MP, O’Hare J, Veale D, et al: Episodes of acute confusion or psychosis in familial hemiplegic migraine. Acta Neurol Scand 1982; 65:369–375Google Scholar

62 . Spranger M, Spranger S, Schwab S, et al: Familial hemiplegic migraine with cerebellar ataxia and paroxysmal psychosis. Eur Neurol 1999; 41:150–152Google Scholar

63 . Al-Semaan Y, Malla AK, Lazosky A: Schizoaffective disorder in a fragile-X carrier. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1999; 33:436–440Google Scholar

64 . Khin NA, Tarleton J, Raghu B, et al: Clinical description of an adult male with psychosis who showed FMR1 gene methylation mosaicism. Am J Med Genet 1998; 81:222–224Google Scholar

65 . Herrlin KM, Hillborg PO: Neurological signs in a juvenile form of Gaucher’s disease. Acta Paediat 1962; 51:137–154Google Scholar

66 . Neil JF, Glew RH, Peters SP: Familial psychosis and diverse neurologic abnormalities in adult-onset Gaucher’s disease. Arch Neurol 1979; 36:95–99Google Scholar

67 . Farlow MR, Yee RD, Dlouhy SR, et al: Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease. I. Extending the clinical spectrum. Neurology 1989; 39:1446–1452Google Scholar

68 . Molina Ramos R, Villanueva Curto S, Molina Ramos JM: Gilbert’s syndrome and schizophrenia. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2006; 34:206–208Google Scholar

69 . Kerbeshian J, Burd L: Are schizophreniform symptoms present in attenuated form in children with Tourette disorder and other developmental disorders. Can J Psychiatry 1987; 32:123–135Google Scholar

70 . Lawlor BA, Most R, Tingle D, et al: Atypical psychosis in Tourette syndrome. Psychosomatics 1987; 28:499–500Google Scholar

71 . Bocchetta A: Psychotic mania in glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase-deficient subjects. Ann Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003; 2:6Google Scholar

72 . Nasr SJ: Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency with psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:1202–1203Google Scholar

73 . Strauss J, DiMartini A: Use of olanzapine in hereditary coproporphyria. Psychosomatics 1999; 40:444–445Google Scholar

74 . McMonagle P, Hutchinson M, Lawlor B: Hereditary spastic paraparesis and psychosis. Eur J Neurol 2006; 13:874–879Google Scholar

75 . Bracken P, Coll P: Homocystinuria and schizophrenia. Literature review and case report. J Nerv Ment Dis 1985; 173:51–55Google Scholar

76 . Freeman JM, Finkelstein JD, Mudd SH: Folate-responsive homocystinuria and “schizophrenia.” A defect in methylation due to deficient 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase activity. N Eng J Med 1975; 292:491–496Google Scholar

77 . Hill KP, Lukonis CJ, Korson MS, et al: Neuropsychiatric illness in a patient with cobalamin G disease, an inherited disorder of vitamin B12 metabolism. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2004; 12:116–122Google Scholar

78 . Hutto BR: Folate and cobalamin in psychiatric illness. Compr Psychiatry 1997; 38:305–314Google Scholar

79 . Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al: Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N EngJ Med 1988; 318:1720–1728Google Scholar

80 . Roze E, Gervais D, Demeret S, et al: Neuropsychiatric disturbances in presumed late-onset cobalamin C disease. Arch Neurol 2003; 60:1457–1462Google Scholar

81 . Ryan MM, Sidhu RK, Alexander J, et al: Homocystinuria presenting as psychosis in an adolescent. J Child Neurol 2002; 17:859–860Google Scholar

82 . Corréa B, Xavier M, Guimarães J: Association of Huntington’s disease and schizophrenia-like psychosis in a Huntington’s disease pedigree. Clin Pract Epidemol Ment Health 2006; 2:1Google Scholar

83 . Jardri R, Medjkane F, Cuisset JM, et al: Huntington’s disease presenting as a depressive disorder with psychotic features. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007; 46:307–308Google Scholar

84 . Glick ID, Graubert DN: Kartagener’s syndrome and schizophrenia: a report of a case with chromosomal studies. Am J Psychiatry 1964; 121:603–605Google Scholar

85 . Quast TM, Sippert JD, Sauvé WM, et al: Comorbid presentation of Kartagener’s syndrome and schizophrenia: support of an etiologic hypothesis of anomalous development of cerebral asymmetry? Schizophr Res 2005; 74:283–285Google Scholar

86 . DeLisi LE, Friedrich U, Wahlstrom J, et al: Schizophrenia and sex chromosome anomalies. Schizophr Bull 1994; 20:495–505Google Scholar

87 . DeLisi LE, Maurizio AM, Svetina C, et al: Klinefelter’s syndrome (XXY) as a genetic model for psychotic disorders. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2005; 135B:15–23Google Scholar

88 . Kebers F, Janvier S, Colin A, et al: What is the interest of Klinefelter’s syndrome for (child) psychiatrists? L’Encéphale 2002; 28:260–265Google Scholar

89 . Visootsak J, Graham JM Jr: Klinefelter syndrome and other sex chromosomal aneuploidies. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2006; 1:42Google Scholar

90 . Reif A, Schneider MF, Hoyer A, et al: Neuroleptic malignant syndrome in Kufs’ disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003; 74:385–387Google Scholar

91 . Federico A, Palmeri S, Malandrini A, et al: The clinical aspects of adult hexosaminidase deficiencies. Dev Neurosci 1991; 13:280–287Google Scholar

92 . Hamner MB: Recurrent psychotic depression associated with GM2 gangliosidosis. Psychosomatics 1998; 39:446–448Google Scholar

93 . Lichtenberg P, Navon R, Wertman E, et al: Post-partum psychosis in adult GM2 gangliosidosis: a case report. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 153:387–389Google Scholar

94 . MacQueen GM, Rosebush PI, Mazurek MF: Neuropsychiatric aspects of the adult variant of Tay-Sachs disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 10:10–19Google Scholar

95 . Navon R, Argov Z, Frisch A: Hexosaminidase A deficiency in adults. Am J Med Genet 1986; 24:179–196Google Scholar

96 . Neudorfer O, Pastores GM, Zeng BJ, et al: Late-onset Tay-Sachs disease: phenotypic characterization and genotypic correlations in 21 affected patients. Genet Med 2005; 7:119–123Google Scholar

97 . Rosebush PI, MacQueen GM, Clarke JT, et al: Late-onset Tay-Sachs disease presenting as catatonic schizophrenia: diagnostic and treatment issues. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:347–353Google Scholar

98 . Zaroff CM, Neudorfer O, Morrison C, et al: Neuropsychological assessment of patients with late onset GM2 gangliosidosis. Neurology 2004; 62:2283–2286Google Scholar

99 . Zelnik N, Khazanov V, Sheinkman A, et al: Clinical manifestations of psychiatric patients who are carriers of Tay-Sachs disease: possible role of psychotropic drugs. Neuropsychobiology 2000; 41:127–131Google Scholar

100 . Iannello S, Bosco P, Cavaleri A, et al: A review of the literature of Bardet-Biedl disease and report of three cases associated with metabolic syndrome and diagnosed after the age of fifty. Obes Rev 2002; 3:123–135Google Scholar

101 . Klein D, Ammann F: The syndrome of Laurence-Moon-Bardet-Biedl and allied diseases in Switzerland: clinical, genetic, and epidemiological studies. J Neurol Sci 1969; 9:479–513Google Scholar

102 . Moore SJ, Green JS, Fan Y, et al: Clinical and genetic epidemiology of Bardet-Biedl syndrome in Newfoundland: a 22-year prospective, population-based, cohort study. Am J Med Genet 2005; 132:352–360Google Scholar

103 . Weiss M, Meshulam B, Wijsenbeek H: The possible relationship between Laurence-Moon-Biedl-Bardet syndrome and a schizophrenic-like psychosis. J Nerv Ment Dis 1981; 169:259–260Google Scholar

104 . De Hert M, Steemans D, Theys P, et al: Lujan-Fryns syndrome in the differential diagnosis of schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet 1996; 67:212–214Google Scholar

105 . Lalatta F, Livini E, Selicorni A, et al: X-linked mental retardation with marfanoid habitus: first report of four Italian patients. Am J Med Genet 1991; 38:228–232Google Scholar

106 . Purandare KN, Markar TN: Psychiatric symptomatology of Lujan-Fryns syndrome: an X-linked syndrome displaying Marfanoid symptoms with autistic features, hyperactivity, shyness and schizophreniform symptoms. Psychiatr Genet 2005; 15:229–231Google Scholar

107 . Van Buggenhout G, Fryns JP: Lujan-Fryns syndrome (mental retardation, X-linked, marfanoid habitus). Orphanet J Rare Dis 2006; 1:26Google Scholar

108 . Leone JC, Swigar ME: Marfan’s syndrome and neuropsychiatric symptoms: case report and literature review. Compr Psychiatry 1986; 27:247–250Google Scholar

109 . Stramesi F, Politi P, Fusar-Poli P: Marfan syndrome and liability to psychosis. Med Hypotheses 2007; 68:1173–1174Google Scholar

110 . Klauck SM, Lindsay S, Beyer KS, et al: A mutation hot spot for nonspecific X-linked mental retardation in the MECP2 gene causes the PPM-X syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2002; 70:1034–1037Google Scholar

111 . Lindsay S, Splitt M, Edney S, et al: PPM-X: a new X-linked mental retardation syndrome with psychosis, pyramidal signs, and macroorchidism maps to Xq28. Am J Hum Genet 1996; 58:1120–1126Google Scholar

112 . Black DN, Taber KH, Hurley RA: Metachromatic leukodystrophy: a model for the study of psychosis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2003; 15:289–293Google Scholar

113 . Kothbauer P, Jellinger K, Gross H, et al: Adult metachromatic leukodystrophy manifested as schizophrenic psychosis (author’s translation). Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr 1977; 224:379–387Google Scholar

114 . Kumperscak HG, Paschke E, Gradisnik P, et al: Adult metachromatic leukodystrophy: disorganized schizophrenia-like symptoms and postpartum depression in 2 sisters. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2005; 30:33–36Google Scholar

115 . Mihaljevic-Peles A, Jakovljevic M, Milicevic Z, et al: Low Arylsulphatase A activity in the development of psychiatric disorders. Neuropsychobiology 2001; 43:75–78Google Scholar

116 . Apostolova LG, White M, Moore SA, et al: Deep white matter pathologic features in watershed regions: a novel pattern of central nervous system involvement in MELAS. Arch Neurol 2005; 62:1154–1156Google Scholar

117 . Finsterer J: Central nervous system manifestations of mitochondrial disorders. Acta Neurol Scand 2006; 114:217–238Google Scholar

118 . Kato T: The other, forgotten genome: mitochondrial DNA and mental disorders. Mol Psychiatry 2001; 6:625–633Google Scholar

119 . Suzuki T, Koizumi J, Shiraishi H, et al: Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy (MELAS) with mental disorder. CT, MRI and SPECT findings. Neuroradiology 1990; 32:74–76Google Scholar

120 . Thomeer EC, Verhoeven WM, van de Vlasakker CJ, et al: Psychiatric symptoms in MELAS; a case report. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998; 64:692–693Google Scholar

121 . Duggal HS: Cognitive affective psychosis syndrome in a patient with sporadic olivopontocerebellar atrophy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005; 17:260–262Google Scholar

122 . Fukutani Y, Katsukawa K, Kobayashi K, et al: Sporadic olivopontocerebellar atrophy with “Subcortical dementia” and hallucinatory paranoid state: report of an autopsy. Dementia and Geriatric Cogn Disorders 1992; 3:95–100Google Scholar

123 . Ziegler B, Tonjes W, Trabert W, et al: Cerebral multisystem atrophy in a patient with depressive hallucinatory syndrome: a case report. Der Nervenarzt 1992; 63:510–514Google Scholar

124 . Bianchin MM, Capella HM, Chaves DL, et al: Nasu-Hakola disease (polycystic lipomembranous osteodysplasia with sclerosing leukoencephalopathy—PLOSL): a dementia associated with bone cystic lesions. From clinical to genetic and molecular aspects. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2004; 24:1–24Google Scholar

125 . Haruta K, Matsunaga S, Ito H, et al: Membranous lipodystrophy (Nasu-Hakola disease) presenting an unusually benign clinical course. Oncol Rep 2003; 10:1007–1010Google Scholar

126 . Kobayashi K, Kobayashi E, Miyazu K, et al: Hypothalamic haemorrhage and thalamus degeneration in a case of Nasu-Hakola disease with hallucinatory symptoms and central hypothermia. Neuropath Appl Neurobiol 2000; 26:98–101Google Scholar

127 . Paloneva J, Autti T, Raininko R, et al: CNS manifestations of Nasu-Hakola disease: a frontal dementia with bone cysts. Neurology 2001; 56:1552–1558Google Scholar

128 . Paloneva J, Kestilä M, Wu J, et al: Loss-of-function mutations in TYROBP (DAP12) result in a presenile dementia with bone cysts. Nat Genet 2000; 25:357–361Google Scholar

129 . Ueki Y, Kohara N, Oga T, et al: Membranous lipodystrophy presenting with palilalia: a PET study of cerebral glucose metabolism. Acta Neurol Scand 2000; 102:60–64Google Scholar

130 . Verloes A, Maquet P, Sadzot B, et al: Nasu-Hakola syndrome: polycystic lipomembranous osteodysplasia with sclerosing leucoencephalopathy and presenile dementia. J Med Genet 1997; 34:753–757Google Scholar

131 . Campo JV, Stowe R, Slomka G, et al: Psychosis as a presentation of physical disease in adolescence: a case of Niemann-Pick disease, type C. Dev Med Child Neurol 1998; 40:126–129Google Scholar

132 . Imrie J, Vijayaraghaven S, Whitehouse C, et al: Niemann-Pick disease type C in adults. J Inherit Metab Dis 2002; 25:491–500Google Scholar

133 . Josephs KA, Van Gerpen MW, Van Gerpen JA: Adult onset Niemann-Pick disease type C presenting with psychosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003; 74:528–529Google Scholar

134 . Shulman LM, David NJ, Weiner WJ: Psychosis as the initial manifestation of adult-onset Niemann-Pick disease type C. Neurology 1995; 45:1739–1743Google Scholar

135 . Walterfang M, Fietz M, Fahey M, et al: The neuropsychiatry of Niemann-Pick type C disease in adulthood. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006; 18:158–170Google Scholar

136 . Bruneau MA, Lespérance P, Chouinard S: Schizophrenia-like presentation of neuroacanthocytosis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2003; 15:378–380Google Scholar

137 . Destounis N, Dincmen K: Salutary effects of prochlorperazine on chronic psychotic choreo-athetosis. Dis Nerv Syst 1966; 27:195–196Google Scholar

138 . Hardie RJ, Pullon HW, Harding AE, et al: Neuroacanthocytosis. A clinical, haematological and pathological study of 19 cases. Brain 1991; 114:13–49Google Scholar

139 . Takahashi Y, Kojima T, Atsumi Y, et al: Case of chorea-acanthocytosis with various psychotic symptoms. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi (Psychiatria et Neurologia Japonica) 1983; 85:457–472Google Scholar

140 . Azzoni A, Argentieri R, Raja M: Neurocutaneous melanosis and psychosis: a case report. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001; 55:93–95Google Scholar

141 . Thomas CS, Toone BK, Rose PE: Neurocutaneous melanosis and psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:649–650Google Scholar

142 . Oner O, Oner P, Deda G, et al: Psychotic disorder in a case with Hallervorden-Spatz disease. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2003; 108:394–398; discussion 397–398Google Scholar

143 . Gillberg C, Forsell C: Childhood psychosis and neurofibromatosis–more than a coincidence? J Autism Dev Disord 1984; 14:1–8Google Scholar

144 . Mouridsen SE, Andersen LB, Sörensen SA, et al: Neurofibromatosis in infantile autism and other types of childhood psychoses. Acta Paedopsychiatr 1992; 55:15–18Google Scholar

145 . Mouridsen SE, Sørensen SA: Psychological aspects of von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis (NF1). J Med Genet 1995; 32:921–924Google Scholar

146 . Bateman JB, Kojis TL, Cantor RM, et al: Linkage analysis of Norrie disease with an X-chromosomal ornithine aminotransferase locus. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1993; 91:299–307; discussion 307–308Google Scholar

147 . Warburg M: Norrie’s disease. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser 1971; 7:117–124Google Scholar

148 . Baron M: Albinism and schizophreniform psychosis: a pedigree study. Am J Psychiatry 1976; 133:1070–1073Google Scholar

149 . Clarke DJ, Buckley ME: Familial association of albinism and schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 155:551–553Google Scholar

150 . Jurius G, Moh P, Levy AB: Oculocutaneous albinism and schizophrenia-like psychosis. J Nerv Ment Dis 1989; 177:112Google Scholar

151 . Yi Z, Garrison N, Cohen-Barak O, et al: A 122.5-kilobase deletion of the P gene underlies the high prevalence of oculocutaneous albinism type 2 in the Navajo population. Am J Hum Genet 2003; 72:62–72Google Scholar

152 . Nanjiani A, Hossain A, Mahgoub N: Patau syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2007; 19:201–202Google Scholar

153 . Sasaki A, Miyanaga K, Ototsuji M, et al: Two autopsy cases with Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease phenotype of adult onset, without mutation of proteolipid protein gene. Acta Neuropathol 2000; 99:7–13Google Scholar

154 . Lowe TL, Tanaka K, Seashore MR, et al: Detection of phenylketonuria in autistic and psychotic children. JAMA 1980; 243:126–128Google Scholar

155 . Pitt D: The natural history of untreated phenylketonuria. Med J Austr 1971; 1:378–383Google Scholar

156 . Richardson MA, Read LL, Clelland JD, et al: Phenylalanine hydroxylase gene in psychiatric patients: screening and functional assay of mutations. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 53:543–553Google Scholar

157 . Seim AR, Reichelt KL: An enzyme/brain-barrier theory of psychiatric pathogenesis: unifying observations on phenylketonuria, autism, schizophrenia, and postpartum psychosis. Med Hypotheses 1995; 45:498–502Google Scholar

158 . Boer H, Holland A, Whittington J, et al: Psychotic illness in people with Prader Willi syndrome due to chromosome 15 maternal uniparental disomy. Lancet 2002; 359:135–136Google Scholar

159 . Clarke D, Boer H, Webb T, et al: Prader-Willi syndrome and psychotic symptoms: 1. Case descriptions and genetic studies. J Intellect Disabil Res 1998; 42:440–450Google Scholar

160 . Descheemaeker MJ, Vogels A, Govers V, et al: Prader-Willi syndrome: new insights in the behavioural and psychiatric spectrum. J Intellect Disabil Res 2002; 46:41–50Google Scholar

161 . Soni S, Whittington J, Holland AJ, et al: The course and outcome of psychiatric illness in people with Prader-Willi syndrome: implications for management and treatment. J Intellect Disabil Res 2007; 51:32–42Google Scholar

162 . Verhoeven WM, Curfs LM, Tuinier S: Prader-Willi syndrome and cycloid psychoses. J Intellect Disabil Res 1998; 42:455–462Google Scholar

163 . Verhoeven WM, Tuinier S: Prader-Willi syndrome: atypical psychoses and motor dysfunctions. Int Rev Neurobiol 2006; 72:119–130Google Scholar

164 . Verhoeven WM, Tuinier S, Curfs LM: Prader-Willi psychiatric syndrome and velo-cardio-facial psychiatric syndrome. Genet Couns 2000; 11:205–213Google Scholar

165 . Verhoeven WM, Tuinier S, Curfs LM: Prader-Willi syndrome: the psychopathological phenotype in uniparental disomy. J Med Genetics 2003; 40:112Google Scholar

166 . Vogels A, De Hert M, Descheemaeker MJ, et al: Psychotic disorders in Prader-Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet 2004; 127A:238–243Google Scholar

167 . Alekseeva N, Kablinger AS, Pinkston J, et al: Hereditary ataxia and behavior. Adv Neurol 2005; 96:275–283Google Scholar

168 . Brandt J, Leroi I, O’Hearn E, et al: Cognitive impairments in cerebellar degeneration: a comparison with Huntington’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2004; 16:176–184Google Scholar

169 . Kanai K, Sakakibara R, Uchiyama T, et al: Sporadic case of spinocerebellar ataxia type 17: treatment observations for managing urinary and psychotic symptoms. Mov Disord 2007; 22:441–443Google Scholar

170 . Leroi I, O’Hearn E, Marsh L, et al: Psychopathology in patients with degenerative cerebellar diseases: a comparison to Huntington’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1306–1314Google Scholar

171 . Liszewski CM, O’Hearn E, Leroi I, et al: Cognitive impairment and psychiatric symptoms in 133 patients with diseases associated with cerebellar degeneration. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2004; 16:109–112Google Scholar

172 . Kalaitzi CK, Sakkas D: Brief psychotic disorder associated with Sturge-Weber syndrome. Eur Psychiatry 2005; 20:356–357Google Scholar

173 . Lee S: Psychopathology in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Can J Psychiatry 1990; 35:674–678Google Scholar

174 . Madaan V, Dewan V, Ramaswamy S, et al: Behavioral manifestations of Sturge-Weber syndrome: a case report. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 8:198–200Google Scholar

175 . Gibson KM, Gupta M, Pearl PL, et al: Significant behavioral disturbances in succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH) deficiency (gamma-hydroxybutyric aciduria). Biol Psychiatry 2003; 54:763–768Google Scholar

176 . Philippe A, Deron J, Geneviè ve D, et al: Neurodevelopmental pattern of succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency (gamma-hydroxybutyric aciduria). Dev Med Child Neurol 2004; 46:564–568Google Scholar

177 . Herkert EE, Wald A, Romero O: Tuberous sclerosis and schizophrenia. Dis Nerv Syst 1972; 33:439–445Google Scholar

178 . Holschneider DP, Szuba MP: Capgras’ syndrome and psychosis in a patient with tuberous sclerosis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1992; 4:352–353Google Scholar

179 . Raznahan A, Joinson C, O’Callaghan F, et al: Psychopathology in tuberous sclerosis: an overview and findings in a population-based sample of adults with tuberous sclerosis. J Intellect Disabil Res 2006; 50:561–569Google Scholar

180 . Sedky K, Hughes T, Yusufzie K, et al: Tuberous sclerosis with psychosis. Psychosomatics 2003; 44:521–522Google Scholar

181 . Zlotlow M, Kleiner S: Catatonic schizophrenia associated with tuberous sclerosis. Psychiatr Q 1965; 39:466–475Google Scholar

182 . Catinari S, Vass A, Heresco-Levy U: Psychiatric manifestations in Turner syndrome: a brief survey. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 2006; 43:293–295Google Scholar

183 . Prior TI, Chue PS, Tibbo P: Investigation of Turner syndrome in schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet 2000; 96:373–378Google Scholar

184 . Hess-Rö ver J, Crichton J, Byrne K, et al: Diagnosis and treatment of a severe psychotic illness in a man with dual severe sensory impairments caused by the presence of Usher syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res 1999; 43:428–434Google Scholar

185 . Jumaian A, Fergusson K: Psychosis in a patient with Usher syndrome: a case report. East Mediterr Health J 2003; 9:215–218Google Scholar

186 . Keats BJ, Corey DP: The Usher syndromes. Am J Med Genet 1999; 89:158–166Google Scholar

187 . Schaefer GB, Bodensteiner JB, Thompson JN Jr, et al: Volumetric neuroimaging in Usher syndrome: evidence of global involvement. Am J Med Genet 1998; 79:1–4Google Scholar

188 . Waldeck T, Wyszynski B, Medalia A: The relationship between Usher’s syndrome and psychosis with Capgras syndrome. Psychiatry 2001; 64:248–255Google Scholar

189 . Wu CY, Chiu CC: Usher syndrome with psychotic symptoms: two cases in the same family. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006; 60:626–628Google Scholar

190 . Ivanov D, Kirov G, Norton N, et al: Chromosome 22q11 deletions, velo-cardio-facial syndrome and early-onset psychosis. Molecular genetic study. Br J Psychiatry 2003; 183:409–413Google Scholar

191 . Sachdev P: Schizophrenia-like illness in velo-cardio-facial syndrome: a genetic subsyndrome of schizophrenia? J Psychosom Res 2002; 53:721–727Google Scholar

192 . Barak Y, Sirota P, Kimhi R, et al: Werner’s syndrome (adult progeria): an affected mother and son presenting with resistant psychosis. Compr Psychiatry 2001; 42:508–510Google Scholar

193 . Hashimoto K, Ikegami K, Nakajima H, et al: Werner syndrome with psychosis. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006; 60:773Google Scholar

194 . Tannock TC, Cook RF: A case of a delusional psychotic syndrome in the setting of Werner’s syndrome (adult progeria). Br J Psychiatry 1988; 152:703–704Google Scholar

195 . Akil M, Schwartz JA, Dutchak D, et al: The psychiatric presentations of Wilson’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1991; 3:377–382Google Scholar

196 . Scheinberg IH, Sternlieb I: Wilson disease and idiopathic copper toxicosis. Am J Clin Nutr 1996; 63:842S–845SGoogle Scholar

197 . Swift RG, Perkins DO, Chase CL, et al: Psychiatric disorders in 36 families with Wolfram syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:775–779Google Scholar

198 . Swift RG, Sadler DB, Swift M: Psychiatric findings in Wolfram syndrome homozygotes. Lancet 1990; 336:667–669Google Scholar

199 . Torres R, Leroy E, Hu X, et al: Mutation screening of the Wolfram syndrome gene in psychiatric patients. Mol Psychiatry 2001; 6:39–43Google Scholar

200 . Crow TJ: Sex chromosomes and psychosis. The case for a pseudoautosomal locus. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 153:675–683Google Scholar

201 . Gillberg C, Winnergard I, Wahlstrom J: The sex chromosomes–one key to autism? An XYY case of infantile autism. Appl Res Ment Retard 1984; 5:353–360Google Scholar

202 . Mors O, Mortensen PB, Ewald H: No evidence of increased risk for schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder in persons with aneuploidies of the sex chromosomes. Psychol Med 2001; 31:425–430Google Scholar

203 . Sorensen K, Nielsen J: Reactive paranoid psychosis in a 47, XYY male. Acta Psychiat Scand 1977; 55:233–236Google Scholar