Cognitive Impairment and Psychiatric Symptoms in 133 Patients With Diseases Associated With Cerebellar Degeneration

Abstract

The authors performed a chart review to determine the frequency with which neurologists detect cognitive and psychiatric symptoms in patients with cerebellar degeneration. Psychopathology, including depression, personality change, cognitive impairment, anxiety, and psychosis was noted in 51% of 133 patients.

Neuroanatomical1,2 and neuropsychological3,4,5,6 observations suggest that the cerebellum modulates cognitive and affective function, and that damage to the cerebellum results in cognitive and affective impairment. Using rigorous diagnostic methods, we recently found that approximately 80% of patients with cerebellar degeneration (CD) experienced one or more psychiatric disorders, a rate similar to that observed in a matched group of patients with Huntington's disease (HD), a disorder characterized by basal ganglia degeneration, and about twice the rate observed in a matched group of neurologically normal individuals.7 While mood disorder was at least as high in the CD group as in the HD group, personality and cognitive changes were more common among HD patients. We have taken advantage of the availability of records from a large group of patients with CD to estimate the rate of cognitive and psychiatric disorders of sufficient severity to be detected on routine neurological examination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We reviewed the neurological records of 213 consecutive patients referred to our Neurogenetics Testing Laboratory for genetic testing. Each patient provided informed consent for both genetic testing and record review. Cases that met the following criteria for CD were included in the study: 1) a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan documenting cerebellar atrophy, 2) a clinical diagnosis of spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) or CD, or 3) the presence of both ataxia and dysmetria on clinical examination. Exclusion criteria included a predominantly parkinsonian clinical presentation or evidence of strokes. A subgroup of CD cases was identified and met one of four criteria for basal ganglia involvement: 1) MRI scan showing basal ganglia atrophy, 2) dystonia, 3) bradykinesia, or 4) chorea.

Psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses were collected using a conservative classification scheme to translate chart notations into simplified DSM-IV terminology. Major depression or depression with suicide attempt = major depression; depression or depressed mood = nonmajor depression; psychosis or schizophrenia = psychotic disorder; persistent changes in temperament or behavior, such as irritability or behavioral disturbance = personality change; anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and panic disorder = an anxiety disorder; mania, with or without depression = bipolar disorder; dementia, memory disturbance, or cognitive impairment = cognitive impairment. The statistical significance of differences between individuals with and without psychopathology was tested using Chi-squared, Fisher's Exact (contingency tables with a bin < 5), and two-tailed Student's t tests. To avoid a Type II error while minimizing type I error, we chose a conservative α level (p < 0.01) rather than a priori correction for multiple comparisons, which might have failed to identify an authentic effect.

RESULTS

One hundred thirty-three cases met both inclusion and exclusion criteria for CD. The neurological diagnosis was SCA or cerebellar ataxia in 75% of cases, multisystem atrophy (MSA) in 15% of cases, and an unspecified gait or movement disorder in 10% of cases. A known SCA mutation was present in 18%. Fifty-nine CD cases (44%) also met criteria for basal ganglia involvement.

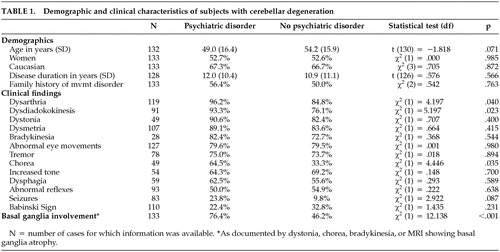

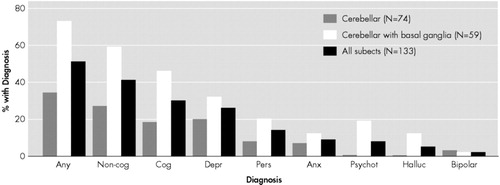

Psychiatric and/or cognitive findings were present in 51% of cases. Forty-one percent of cases had psychiatric symptoms, and 30% had cognitive impairment (Figure 1). The rate of cognitive impairment and most types of noncognitive psychopathology were significantly higher in CD cases with basal ganglia involvement. The most common psychiatric manifestation was depression, both major depression and nonmajor depressive disorder, which was not significantly more frequent in cases with basal ganglia involvement. Personality change, anxiety disorder, psychotic disorders, and hallucinations were also common, with the latter two diagnoses found only in cases with basal ganglia involvement.

Demographic and other variables did not significantly differ between the groups with and without psychiatric disorders (Table 1). The frequency of neurological signs, except for signs resulting from basal ganglia damage, did not significantly differ between the two groups. Cognitive impairment was nearly three times more frequent in patients who also had psychiatric findings (49% versus 17%, df = 1, χ2 = 8.78, p = 0.003).

DISCUSSION

Overall, cognitive impairment or psychiatric symptoms were noted in about one-half of all CD cases. Depression and depressive symptoms were the most commonly observed noncognitive psychiatric phenomena, but personality change, anxiety, and psychosis were also detected at relatively high rates. These findings are consistent with our hypothesis that diseases involving cerebellar degeneration, and to a lesser extent cerebellar degeneration itself, result in a high rate of cognitive and psychiatric phenomena, and these phenomena are of sufficient severity and clinical relevance to be detected on routine neurological evaluation.

As expected, psychiatric disorders associated with cerebellar degeneration were detected much less frequently in the course of routine neurological examination than in our systematic evaluation of psychopathology (41% versus 77%).7 Unexpectedly, however, the rate of cognitive impairment in cases of cerebellar degeneration without basal ganglia involvement was about the same in the two studies (18% versus 19%). This similarity may reflect a difference in the threshold for detecting cognitive impairment and psychiatric abnormalities on routine examinations or that factors such as dysarthria and personality change differentially influenced cognitive assessment in the two studies. Patient ascertainment may also have led to the higher than anticipated rates of cognitive impairment in the current study.

Are the psychiatric findings in these cases a direct result of neuropathology? For depression, this issue is difficult to resolve. Chronic, debilitating diseases of many types have been associated with high rates of depression,8 but there is also evidence of a specific association between neuropathological processes and depression.9 Our results do not clearly distinguish the specific and nonspecific relationship between neurodegeneration and depression. However, other forms of psychopathology noted in our sample, including personality change, psychotic disorders, and hallucinations, are not readily explainable as psychological reactions to chronic disease, and they occurred with greater frequency than in the general population.10 This finding further supports our hypothesis that at least a portion of the psychiatric symptoms of CD are a direct result of neuronal degeneration.

The finding that psychopathology and cognitive impairment were more frequent in patients with basal ganglia involvement is unlikely to be an artifact of more complete documentation since the rates of most other neurological signs are the same in the groups with and without psychiatric symptoms. This result may, instead, reflect nonspecifically greater severity of neurodegeneration in cases with basal ganglia involvement or a more specific correlation of basal ganglia pathology to cognitive and psychiatric abnormalities. The latter possibility is not inconsistent with our previous findings, which showed that while the overall frequency of psychiatric phenomena was similar in CD and HD, there were substantially more frequent personality changes and cognitive impairment in the HD cases and a tendency toward greater severity of the psychopathology.7

The results of this study must be viewed with caution in light of the limitations of retrospective chart reviews, including biases in subject ascertainment, limitations in the data available in patient records, and the lack of systematic protocols for the diagnosis and notation of psychopathology. Nonetheless, the findings generally confirm our previous results that show clinically significant cognitive and psychiatric disorders, many potentially amenable to pharmacological or other forms of treatment, are common in patients with cerebellar degeneration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the patients and their referring neurologists who made this study possible and Dr. Mark Molliver for his guidance. The work was supported by NARSAD Independent Investigator Award, NIH NS16375 and NS38054, and the Stanley Scholars Fund.

|

FIGURE 1. Psychopathology in Subjects With Cerebellar Degeneration

aThe percentage of patients with a given diagnosis is depicted for the CD only and the CD plus basal ganglia disease groups, separately and combined. Diagnostic categories are described in the text. Abbreviations: Any=any diagnosis; non-cog=any noncognitive diagnosis; Cog=any cognitive diagnosis; Depr=major or nonmajor depression; Pers=personality change; Anx=anxiety-related diagnoses; Psychot=nonaffective psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia; Halluc=isolated hallucinations; Bipolar=bipolar affective disorder. The following disorders were significantly more frequent in CD patients with basal ganglia findings than in the patients with CD only: any disorder (χ2=20.08, df=1, p<0.0001), any noncognitive disorder (χ2=20.08, df=1, p=0.0002), cognitive impairment (χ2=20.08, df=1, p<0.0004), psychotic disorder (p=0.0001, Fisher’s exact test), and hallucinations (p=0.0027, Fisher’s exact test).

1 Middleton FA, Strick PL: Basal ganglia and cerebellar loops: motor and cognitive circuits. Brain Res Rev 2000; 31:236–250Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Schmahmann JD: From movement to thought: Anatomical substrates of the contribution to cognitive processing. Human Brain Map 1996; 4:174–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Schmahmann JD: The cerebellum and cognition. San Diego: Academic Press, 1997Google Scholar

4 Kish SJ, el-Awar M, Schut L, et al: Cognitive deficits in olivopontocerebellar atrophy: implications for cholinergic hypothesis of Alzheimer's dementia. Ann Neurol 1988; 24:200–206Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Kish SJ, El-Awar M, Stuss D, et al. Neuropsychological test performance in patients dominantly inherited spinocerebellar ataxia: Relationship to ataxia severity. Neurol 1994; 44:1738–1746Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Schmahmann JD, Sherman JC: The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. Brain 1998; 121:561–579Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Leroi I, O'Hearn E, Marsh L, et al: Psychopathology in degenerative cerebellar diseases: A comparison to Huntington's disease and normal controls. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1306–1314Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Cassen EH. Depressive disorders in the medically ill: an overview. Psychosomatics 1995; 36:S2-S10.Google Scholar

9 Starkstein SE and Robinson RG, eds. Depression in Neurological Disease. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.Google Scholar

10 Eaton WW, Regier DA, Locke BZ, Taube CA. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program of the National Institutes of Mental Health. Public Health Rep 1981; 96:319–325Medline, Google Scholar