Apolipoprotein E Genotype and Odor Identification in Schizophrenia

METHOD

Participants

Twenty-eight patients with a DSM-IV 9 diagnosis of schizophrenia (14 men, 14 women) and 26 healthy volunteers (15 men, 11 women) were recruited from the Schizophrenia Research Center at the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center. Subjects were matched for sex (χ 2 =0.32, df=1, p=0.57) and race (χ 2 =2.7, df=1, p=0.10). Patients were older than healthy comparison subjects (mean ages of 36.6 [SD=9.1] years and 29.4 [SD=11.2] years, respectively; t=26, df=52, p=0.01). Age was subsequently used as a covariate in all analyses. Due to the fact that schizophrenia adversely affects educational attainment, it was expected that patients attained fewer years of formal education than healthy comparison subjects (t=−2.0, df=52, p=0.04). However, parental education, a more appropriate indicator of preillness educational expectation, revealed no significant difference between groups (Wilks’ λ (2, 51)=0.96, p=0.38). Patients tended to smoke more than comparison subjects (mean pack-years: patients = 7.7 [SD=11.2]; comparison subjects=2.4 [SD=7.4]; t (49)=1.9, p<0.053). All patients met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia, with no other concurrent diagnoses. Healthy subjects were free of any Axis I diagnosis, Axis II Cluster A (i.e., schizoptypal, schizoid, or paranoid) personality disorder, and family history of psychiatric illness.

Subjects were excluded if they had a history of neurological disorder, including head trauma with loss of consciousness; a history of substance abuse or dependence (as assessed by history, record review, and serum toxicology); a history of any medical condition that might alter cerebral functioning; or a recent respiratory infection or any other condition that could affect olfactory functioning (e.g., common cold or allergies). Written informed consent was obtained after the procedures had been fully explained.

ApoE Genotyping

Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) genotyping was performed on blood using polymerase chain reaction-based methods. 10 ApoE genotypes for each subject were scored independently by two observers who were blind to diagnostic status, and allele frequencies were calculated for each group.

Olfactory Assessment

Odor identification skills were assessed with the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT). 11 The UPSIT was administered unilaterally (each nostril separately), with the contralateral naris occluded using a piece of Durapore TM tape (3M Corporation, Minneapolis, MN) fitted tightly over the edges of the nostril. This procedure effectively isolated the nostril being examined and prevented retronasal airflow. Two booklets of the test were administered to the left nostril, and two to the right nostril, with the booklets systematically counterbalanced among subjects.

Statistical Methods

The relationship between ApoE genotype and UPSIT performance was probed in two ways. First, each group was divided into two subgroups based on the presence or absence of at least one ϵ4 allele. These ϵ4-positive and ϵ4-negative subgroups were then contrasted with regard to UPSIT performance using multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) with age as a covariate. Second, in order to gauge any potential “dose-effect” relationships, each subject’s ApoE genotype was graded on a 5-point scale with the ApoE ϵ2/2 genotype representing the lowest point and ApoE ϵ4/4 the highest point. Employing such a scale incorporated all combinations of the three alleles: 1) the possible protective effects of the ϵ2 allele, 2) presumed neutral effect of the ϵ3 allele, and 3) the putative negative effect of the ϵ4 allele. These relationships were examined using Spearman correlations.

RESULTS

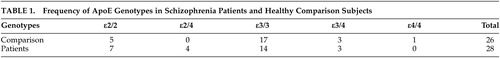

Consistent with prior studies, there were no significant differences between diagnostic groups for ApoE gene frequencies (χ 2 =0.77, df=1, p=0.38) ( Table 1 ).

|

Results revealed no significant difference in UPSIT performance for either nostril between ϵ4-positive and ϵ4-negative subgroups in the patient group (F(1, 26)=0.08, p=0.78) or in the healthy subjects group (F(1, 24)=0.37, p=0.54). Spearman correlations of ApoE grade and UPSIT performance did not reveal any significant relationship in patients (p > 0.28) or in healthy subjects (p > 0.08) across nostrils. No significant main effects of sex, diagnosis by sex interactions, or sex-specific correlations with APOE status or olfactory measures were observed.

DISCUSSION

Data reported in this study do not support an effect of ApoE allele status on the expression of odor identification deficits in patients with schizophrenia. By and large, prior investigations of the ϵ4 allele in schizophrenia have not supported a greater prevalence of this allele in patients but have suggested that genetic status may influence expression of the disease (i.e., younger age of onset). 10 , 12 , 13 In older patients, the ϵ4 allele has been associated with coexistent dementia as well as more neurofibrillary pathology on postmortem. 10 While there appears to be a genetic contribution to olfactory processing deficits in patients with schizophrenia, these deficits do not appear to be mediated at the level of the ApoE allele. Thus, they are likely to have an etiology that is distinct from the olfactory processing deficits observed in Alzheimer’s disease.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the sample size was relatively small, perhaps limiting the distribution of genotypes in each group. It is notable, however, that the current ApoE genotype distribution described is generally consistent with other studies in the literature. 10 , 14 Second, only odor identification abilities were examined. Future studies might determine whether the findings in our study could be applied to other olfactory domains.

1. Martzke JS, Kopala LC, Good KP: Olfactory dysfunction in neuropsychiatric disorders: review and methodological considerations. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 42(8):721–732Google Scholar

2. Moberg PJ, Turetsky, B.I: Scent of a disorder: olfactory functioning in schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2003; 5:311–319Google Scholar

3. Moberg PJ, Arnold SE, Doty RL, et al: Impairment of odor hedonics in men with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1784–1789Google Scholar

4. Kopala LC, Good KP, Morrison K, et al: Impaired olfactory identification in relatives of patients with familial schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158(8):1286–1290Google Scholar

5. Kopala LC, Good KP, Torrey EF, et al: Olfactory function in monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155(1):134–136Google Scholar

6. Murphy C, Bacon AW, Bondi MW, et al: Apolipoprotein E status is associated with odor identification deficits in nondemented older persons. Ann NY Acad Sci 1998; 855:744–750Google Scholar

7. Graves AB, Bowen JD, Rajaram L, et al: Impaired olfaction as a marker for cognitive decline: interaction with apolipoprotein E epsilon4 status. Neurology 1999; 53:1480–147Google Scholar

8. Bacon AW, Bondi MW, Salmon DP, et al: Very early changes in olfactory functioning due to Alzheimer’s disease and the role of apolipoprotein E in olfaction. Ann NY Acad Sci 1998; 855:723–731Google Scholar

9. APA: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

10. Arnold SE, Joo E, Martinoli MG, et al: Apolipoprotein E genotype in schizophrenia: frequency, age of onset, and neuropathologic features. Neuroreport 1997; 8:1523–156Google Scholar

11. Doty RL, Shaman P, Dann M: Development of the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test: a standardized microencapsulated test of olfactory function. Physiol Behav 1984; 32(3):489–502Google Scholar

12. Malhotra AK, Breier A, Goldman D, et al: The apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele is associated with blunting of ketamine-induced psychosis in schizophrenia. A preliminary report. Neuropsychopharmacology 1998; 19:445–448Google Scholar

13. Schurhoff F, Krebs MO, Szoke A, et al: Apolipoprotein E in schizophrenia: a French association study and meta-analysis. Am J Med Genet 119B(1):18–23, 2003Google Scholar

14. Lan TH, Hong CJ, Chen JY, et al: Apolipoprotein E-epsilon 4 frequency in patients with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 42(3):225–227, 1997Google Scholar