Neuropsychiatric Manifestations of Multiple Sclerosis

Abstract

The range of neuropsychiatric symptoms in multiple sclerosis (MS) has not been prospectively assessed. The authors, working at a tertiary medical center in Mexico City, used the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) to evaluate neuropsychiatric symptoms prospectively in 44 MS patients who were stable between relapses and 25 control subjects of similar age, education, and cognitive function. Neuropsychiatric symptoms were present in 95% of patients and 16% of control subjects. Changes present were depressive symptoms (79%), agitation (40%), anxiety (37%), irritability (35%), apathy (20%), euphoria (13%), disinhibition (13%), hallucinations (10%), aberrant motor behavior (9%), and delusions (7%). The only relationships with MRI were between euphoria and hallucinations and moderately severe MRI abnormalities. The authors conclude that diverse types of neuropsychiatric symptoms are common in MS; symptoms are present between exacerbations; and there are variable correlations with MRI abnormalities.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory demyelinating disease involving the cerebral hemispheres, optic nerves, brainstem, cerebellum, and spinal cord.1 MS has protean clinical features, including optic neuritis, weakness, sensory abnormalities, and cerebellar signs.2 Cognition and emotional function also are affected. Severe dementia is relatively uncommon in MS, but mild to moderate cognitive deficits are detected in 43% to 65% of patients assessed with neuropsychological tests.3 Depression is the most commonly reported neuropsychiatric symptom in MS, occurring in 37% to 54% of patients over the course of the disease.4 Euphoria, mania, psychosis, anxiety, personality syndromes, and eating disorders have also been described.4–10

Neuropsychiatric studies of MS have usually focused on a single symptom such as depression or euphoria, have typically used instruments not developed for use with neurologically ill patients, have commonly reported symptoms in small patient samples, and often have been based on retrospective chart reviews of psychiatric symptoms. Relatively few studies have used prospective assessments with multisymptom tools developed for use in neurologic disorders with neuropsychiatric manifestations or have investigated the structural correlates of behavioral changes in MS.

To better understand the neuropsychiatric dimension of MS, we conducted a prospective neuropsychiatric assessment of 44 patients with MS and 25 healthy control subjects. A comprehensive neuropsychiatric symptom inventory was used to assess the presence of neuropsychiatric disorders. The extent of psychopathology in the MS patients was correlated with the severity of lesions observed on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Given the importance of the limbic system and associated paralimbic brain regions in mediating emotional function, we hypothesized that depression, psychosis, disinhibition, and euphoria would correlate with the extent of MRI lesions in frontal and temporal regions. We sought relationships between neuropsychiatric disturbances and changes in the frontal and temporal lobes.

METHODS

Forty-four patients attending the National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery in Mexico City, a tertiary medical center and the largest referral center in Mexico, were included in the study. Eligible patients met Research Diagnostic Criteria for clinically definite MS11 and had undergone complete assessments with neurological examination and MRI. None of the patients were receiving steroids or psychotropic medications at the time of the neuropsychiatric assessment, and none were in acute periods of exacerbation of their MS. Forty patients had clinical courses consistent with relapsing and remitting MS and 4 had chronic progressive MS. Patients with a history of head trauma, other neurological illness, or major psychiatric illness antedating the onset of the MS were excluded. Few patients with advanced disease are followed in this clinic, and such cases are underrepresented in the study sample. Participants had to have a caregiver who lived in the household and who would serve as an informant regarding the patient's behavior.

Twenty-five healthy control subjects participated in the study. They consisted of family members as well as students and hospital personnel who met the same exclusion criteria as the MS patients. The control group was constructed to have the same mean age, education, and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)12 scores as the patient group and to have a similar gender distribution. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Research assessments included the Extended Disability Status Scale (EDSS),13 MMSE,12 and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI).14 The primary outcome assessment was the NPI; the EDSS and MMSE were collected to help characterize the population and to seek correlations between cognitive changes and disease severity with the neuropsychiatric symptoms of interest. Information for the NPI was obtained for MS patients and control subjects from a relative living with the study participant. The EDSS, MMSE, and NPI were administered during the same clinic visit.

The NPI is a caregiver-based rating scale of established validity and reliability.14 It assesses 10 neuropsychiatric domains, including delusions, hallucinations, agitation, dysphoria, anxiety, euphoria, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, and aberrant motor activity such as pacing and stereotyped behaviors. NPI scores are based on behaviors present in the past month. Each behavior is evaluated by using a standardized script read by the examiner. The symptom is then scored by the caregiver, using operationalized criteria for frequency and severity. The subscale score is the product of frequency×severity. A total NPI score is obtained by summing the 10 domain scores. The NPI is a dimensional assessment instrument that determines symptom presence and provides a score that reflects symptom severity and frequency; it does not provide categorical diagnoses such as major depression. The NPI has been used to assess neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with Alzheimer's disease,15 frontotemporal dementia,16 and progressive supranuclear palsy.17

The NPI was translated into Spanish by research workers from the Laboratory of Experimental Psychology of the National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery and back-translated to ensure accuracy of translation. A reliability study of the translated version was carried out. Ten interrater and 10 test-retest interviews were conducted. The translated instrument was found to retain the characteristics of the original: interrater correlations for the 10 subtests ranged from 0.82 to 0.94 and test-retest correlations ranged from 0.85 to 0.95.

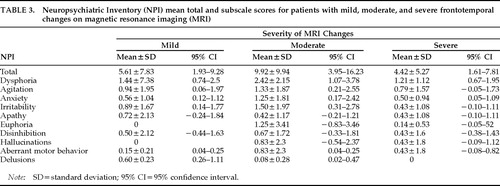

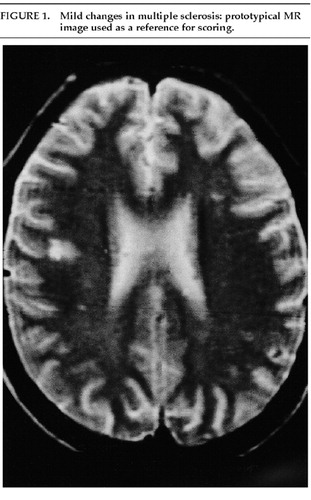

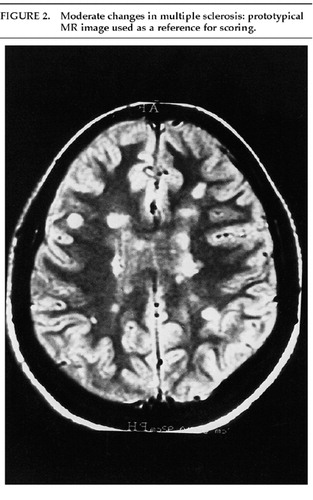

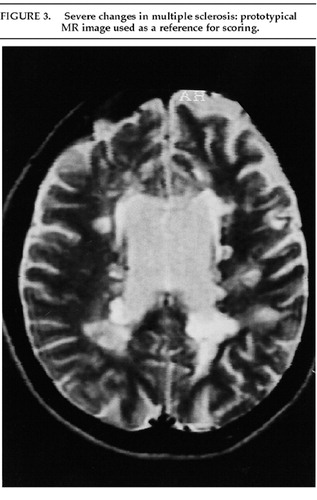

Gadolinium-enhanced MR images were available on all patients and had been performed within 9 months of the time of the research assessment. Gadolinium-enhanced T2-weighted images were assessed by three neurologists expert in MRI interpretation and blind to information regarding the patient's clinical status. The degree of white matter pathology in the frontotemporal regions was rated as mild, moderate, or severe based on the number, size, and activity of the demyelinating lesions. Our hypothesis was focused on changes in the frontotemporal regions, and lesions in other brain regions were not assessed. Anatomic localization of the lesions was based on an atlas,18 and severity ratings were based on comparisons with prototypical images that provided a reference for scoring (Figures 1, 2, and 3). An interrater reliability study of the severity rating technique revealed that 95% of images were scored the same (no significant differences were found among the three raters). Control subjects did not have an MRI. The interval between administration of the NPI and obtaining an MRI may have compromised our ability to find relationships between the clinical and the radiological changes.

Statistical analyses used nonparametric Mann-Whitney U-tests to compare NPI scores of the MS patient group with the scores of the control group. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to explore differences in NPI subscale scores in MS patients with varying severity of white matter changes revealed by MRI. Statistical significance was accepted at P<0.05 level. Means and standard deviations are reported to describe continuous variables; additionally, 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) are provided for mean scores and ratings.

RESULTS

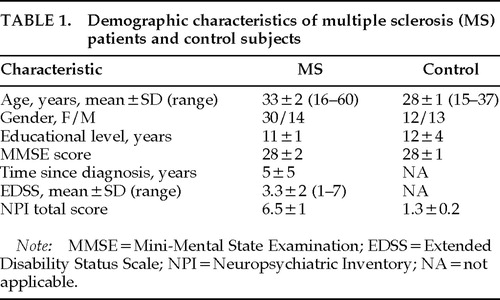

Demographic characteristics of the MS patients and control subjects are presented in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences in age, gender distribution, education, or MMSE scores between the patient and control groups.

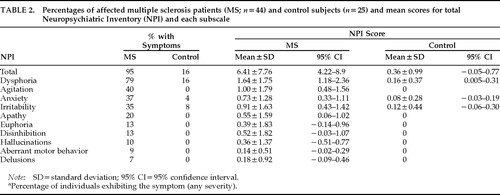

Percentages of affected patients and control subjects and mean scores for the NPI and its subscales are presented in Table 2. Ninety-five percent of MS patients exhibited some degree of psychopathology on the NPI (Table 2). The mean total NPI score in the MS patients was 6.5±1 (range 0–34), significantly greater than the score obtained by control subjects (1.3±0.2; range 0–5; P<0.001). In MS patients, dysphoria was the most common symptom (79%), followed by agitation (40%), anxiety (37%), irritability (35%), apathy (20%), euphoria (13%), disinhibition (13%), hallucinations (10%), aberrant motor behavior (9%), and delusions (7%). Mean NPI subscale scores revealed that the most severe symptoms were dysphoria, agitation, anxiety, and irritability; all had mean scores above 0.7.

Eighty-four percent of the control group had no neuropsychiatric symptoms (P<0.001 compared with the MS patients). Four control subjects had symptoms of dysphoria, and 2 each had anxiety and irritability.

Within the MS patient group, there was no significant relationship of patient age to NPI symptom scores, and men and women had similar symptom profiles. No correlations were found between EDSS or MMSE scores and the NPI scores in the patient group. The number of patients with chronic progressive MS (n=4) was too small to allow a separate analysis of the neuropsychiatric symptoms of chronic progressive and relapsing-remitting forms of the disease.

When the MRIs were analyzed, all had ratable pathology: 18 showed mild frontotemporal changes (40%), 12 showed moderate changes (27%), and 14 showed severe abnormalities (32%). NPI total and subscale scores for patients with mild, moderate, and severe MS are shown in Table 3. The total NPI scores did not correlate with the degree of demyelination. Seven of 10 NPI subscale scores were highest in patients with moderate frontotemporal changes, and this difference reached statistical significance for euphoria and hallucinations (P<0.01).

DISCUSSION

The principal conclusion of this study is that neuropsychiatric symptoms of at least mild degree are very common among MS patients even when their disease is early or mild in severity. Prospective assessment with a multisymptom rating scale such as the NPI, designed for use with patients with neurological illness, reveals a greater range of psychopathology in MS than do studies using retrospective chart reviews, assessment tools designed primarily for idiopathic psychiatric disorders, categorical diagnoses, or instruments that assess a limited range of symptoms.

Ninety-five percent of these unselected patients were symptomatic, and even patients with mild changes in the frontal and temporal regions on MRI evidenced psychopathology measurable on the NPI. This high prevalence is particularly dramatic in a population of patients who were not experiencing acute relapses of sensorimotor symptoms at the time of assessment and who had relatively mild disease. Symptoms of depression (dysphoria) were the most common, occurring in nearly 80% of patients. Agitation, anxiety, and irritability were present in one-third of patients, and apathy, euphoria, disinhibition, hallucinations, purposeless behaviors, and delusions occurred in smaller numbers of patients. The neuropsychiatric symptoms tended to be of mild severity, although all symptoms were more common in patients than in matched control subjects. A few control patients exhibited dysphoria, anxiety, and irritability.

Mood changes have been found to be the most common neuropsychiatric symptoms in MS, and when neurologic symptoms are mild, patients may be misdiagnosed as suffering from a primary mood disorder.19 In an early, seminal investigation by Surridge,20 27% of 1,098 MS patients had depressive symptoms. In several other studies, depression was identified in 40% to 60% of patients with MS.21–24 We identified mood changes (not necessarily major depression) in 79% of patients.

Depression scale scores may be artificially elevated in MS patients because they include vegetative symptoms and evaluative symptoms (such as feelings of uselessness),25 but the NPI dysphoria scale contains only mood-related symptoms and was constructed to avoid this assessment problem common in evaluating depression in patients with neurologic disorders.

In results similar to ours, neither Joffe et al.21 nor Huber et al.26 found significant correlations between disease severity and depressive symptoms, although Whitlock and Siskind24 found disability and Beck Depression Inventory scores to be significantly but modestly correlated. The absence of a compelling association between disability and depression argues for a neurobiologic etiology for the depressive disorder. Moreover, Sabatini et al.27 showed significant asymmetries of perfusion of limbic cortex in depressed compared with nondepressed MS patients even when there were no detectable differences on the MRIs of the two groups. Functional imaging may be more useful than MRI for investigating the neurobiologic substrates of depression in MS.

Euphoria, defined as unusual cheerfulness and lack of concern about disability, was identified by Rabins et al.28 in 48% of 87 MS patients; the euphoric patients had larger ventricles on computed tomography than noneuphoric patients. Joffe et al.21 reported hypomania in 3% of their patients and present or past mania in an additional 13%. Surridge20 identified euphoria in 18.5% of nearly 1,100 patients, and Minden et al.22 reported mania in 4% and hypomania in 28% of patients. We found euphoria in 13% of our patient sample.

Personality changes also occur in MS but have received little study. Surridge20 noted irritability in 40.7% and apathy in 10% of MS patients. We found irritability (35%), apathy (20%), and disinhibition (13%) in our MS patients. Reischies et al.29 identified a significant correlation between periventricular lesion score and an irritability measure. The NPI reveals that personality changes are among the most common changes of MS and will not be detected by tools that lack questions concerning this aspect of behavior. Apathy also has been found to be a common feature of other neurological illnesses, including Alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal dementias, and progressive supranuclear palsy.15–17

Anxiety has received little investigation in MS. Joffe et al.21 observed that 5% of their patients had evidence of generalized anxiety and 6% had panic attacks. Minden et al.22 reported that 8% of their patients had had anxiety disorders prior to the onset of their MS, whereas 24% had anxiety disorders after the onset. Symptoms of anxiety were recorded in 37% of patients in the current sample. Anxiety of at least mild severity may be more common than previously thought in MS.

Psychosis is uncommon in MS. Surridge20 found evidence of a “schizophreniform” psychosis in 1 of 108 patients, and Joffe et al.21 observed no psychotic patients in their series of 100 patients with MS. Ron and Logsdail30 found 4 cases of delusional disorder and 3 of atypical psychosis among 110 MS patients. Three of the patients in the current study had had delusional symptoms in the month prior to assessment and 4 had had hallucinations. In many cases, psychosis has been associated with advanced demyelination,31,32 but in the current study the psychotic patients did not have significantly more severe disease than patients without psychosis. Thus, in some cases psychosis may occur as an early feature of MS.

In this study, there were relatively few correlations between MRI changes and NPI subscale scores. Euphoria and hallucinations were more common in patients with moderately severe frontotemporal MRI abnormalities. These symptoms have previously been linked to brain changes in these regions in a variety of diseases.33 Honer et al.34 found that MRI abnormalities were more common in the temporal lobes in patients with mixed types of psychopathology than in patients without neuropsychiatric symptoms. Reischies et al.29 failed to find any relationship between depression and periventricular lesion scores, although they did demonstrate relationships with euphoria and irritability. Ron and Logsdail30 found no association between global measures of psychiatric disability and MRI changes, but they reported a correlation between delusions and the degree of pathology in the temporoparietal regions. As noted above, functional imaging may be superior to structural imaging for studying the neuroanatomy of neuropsychiatric symptoms in MS.27

The observations reported here and those by previous investigators indicate that neuropsychiatric symptoms are common manifestations of MS. Mood changes are the most frequent but are not the only type of psychopathology evidenced in MS patients. Personality changes, anxiety, and, rarely, psychosis also occur. Neuropsychiatric symptoms can produce substantial disability, and detecting them among MS patients may allow improved management of their condition. Multisymptom, scaled assessment tools such as the NPI facilitate the detection and characterization of psychopathology in MS patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank M. Villeda, M.D., and I. Ruiz, M.D., for evaluation of MRI studies and J. Sotelo, M.D., for useful comments on the manuscript. This project was partially supported by National Council on Science and Technology of Mexico (CONACYT) Grant 0001P-M9505, National Institute on Aging Alzheimer's Disease Center Grant AG10123, and the Sidell-Kagan Research Fund.

|

|

|

FIGURE 1. Mild changes in multiple sclerosis: prototypical MR image used as a reference for scoring.

FIGURE 2. Moderate changes in multiple sclerosis: prototypical MR image used as a reference for scoring.

FIGURE 3. Severe changes in multiple sclerosis: prototypical MR image used as a reference for scoring.

1 Adams RD, Victor M: Principles of Neurology, 5th edition. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1993Google Scholar

2 Matthews WB: Multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases: clinical features, in Clinical Neurology, edited by Swash M, Oxbury J. New York, Churchill Livingstone, 1991, pp 1106–1116Google Scholar

3 Rao SM: Cognitive and neuroimaging changes in multiple sclerosis, in Multiple Sclerosis: A Neuropsychiatric Disorder, edited by Halbreich U. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993, pp 55–71Google Scholar

4 Minden SL, Schiffer RB: Depression and affective disorders in multiple sclerosis, in Multiple Sclerosis: A Neuropsychiatric Disorder, edited by Halbreich U. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993, pp 33–54Google Scholar

5 Logsdail SJ, Callanan MM, Ron MA: Psychiatric morbidity in patients with clinically isolated lesions of the type seen in multiple sclerosis: a clinical and MRI study, in Mental Disorders and Cognitive Deficits in Multiple Sclerosis, edited by Jensen K, Knudsen L, Stenager E, et al. London, John Libbey, 1989, pp 153–165Google Scholar

6 Rabins PV: Euphoria in multiple sclerosis, in Neurobehavioral Aspects of Multiple Sclerosis, edited by Rao SM. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990, pp 180–185Google Scholar

7 Craig A: Patients presenting with anxiety and mood disturbance: the importance of correct diagnosis. Behavioral Changes 1993; 10:86–92Crossref, Google Scholar

8 Moler A, Wiedemann G, Rohde U, et al: Correlates of cognitive impairment and depressive mood disorder in multiple sclerosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 23:117–121Crossref, Google Scholar

9 Sadovnick AD, Remick RA, Allen J, et al: Depression and multiple sclerosis. Neurology 1996; 46:628–632Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Skegg K: Multiple sclerosis as a pure psychiatric disorder. Psychol Med 1993; 23:909–914Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Poser C, Donal P, Scheinberg L, et al: New diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines for research protocols. Ann Neurol 1983; 13:227–231Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the mental state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Kurtze JF: Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983; 33:1444–1452Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al: The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994; 44:2308–2314Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Mega MS, Cummings JL, Fiorello T, et al: The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1996; 46:130–135Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Levy M, Miller B, Cummings JL, et al: Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementias: behavioral distinctions. Arch Neurol 1996; 53:687–690Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Litvan I, Mega M, Cummings JL, et al: Neuropsychiatric aspects of progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurology 1996; 47:876–883Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Damasio H: Human Brain Anatomy in Computerized Images. New York, Oxford University Press, 1995Google Scholar

19 Lyoo IK, Seol HY, Byun HS, et al: Unsuspected multiple sclerosis in patients with psychiatric disorders: a magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1996; 8:54–59Link, Google Scholar

20 Surridge D: An investigation into some psychiatric aspects of multiple sclerosis. Br J Psychiatry 1969; 115:749–764Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Joffe RT, Lippert GP, Gray TA, et al: Mood disorder and multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 1987; 44:376–378Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Minden SL, Orav J, Reich P: Depression in multiple sclerosis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1987; 9:426–434Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Schiffer RB, Caine ED, Bamford KA, et al: Depressive episodes in patients with multiple sclerosis. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:1498–1500Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Whitlock FA, Siskind MM: Depression as a major symptom of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1980; 43:861–865Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Nyenhuis DL, Rao SM, Zajecka JM, et al: Mood disturbance versus other symptoms of depression in multiple sclerosis. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 1995; 1:291–296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Huber SJ, Rammohan KW, Bornstein RA, et al: Depressive symptoms are not influenced by severity of multiple sclerosis. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1993; 6:177–180Google Scholar

27 Sabatini U, Pozzilli C, Pantano P, et al: Involvement of the limbic system in multiple sclerosis patients with depressive disorders. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 39:970–975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Rabins PV, Brooks BR, O'Donnell P, et al: Structural brain correlates of emotional disorders in multiple sclerosis. Brain 1986; 109:585–597Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Reischies FM, Baum K, Nehrig C, et al: Psychopathological symptoms and magnetic resonance imaging findings in multiple sclerosis. Biol Psychiatry 1993; 33:676–678Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Ron MA, Logsdail SJ: Psychiatric morbidity in multiple sclerosis: a clinical and MRI study. Psychol Med 1989; 19:887–895Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Felgenhauer K: Psychiatric disorders in the encephalitic form of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 1990; 237:11–18Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 Neumann PE, Mehler MF, Horoupain DS, et al: Atypical psychosis with disseminated subpial demyelination. Arch Neurol 1988; 45:634–636Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 Trimble MR: Biological Psychiatry, 2nd edition. New York, Wiley, 1996Google Scholar

34 Honer WG, Hurwitz T, Li DKB, et al: Temporal lobe involvement in multiple sclerosis patients with psychiatric disorders. Arch Neurol 1987; 44:187–190Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar