Neurological Signs and Cognitive Performance Distinguish Between Adolescents With and Without Psychosis

Several studies suggest that subtle signs of neurological dysfunction (“soft signs”) are relatively common among children and adolescents with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. 6 – 8 Additionally, Karp et al. 8 demonstrated a failure of age-expected reductions in the number and severity of these signs among adolescents with schizophrenia, suggesting that psychosis developing in this age range, and perhaps in older individuals as well, is associated with other signs of aberrant neurodevelopment.

Studies pairing neurological assessment with either symptom severity or cognitive performance among adolescents with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders have not been published. Additionally, studies of this population have not employed standardized neurological assessment scales, thereby limiting the comparability of their findings to those of adults with these conditions. The Neurological Examination Scale (NES) 2 is a standardized clinical assessment of subtle (“soft”) neurological signs with excellent construct validity and interrater reliability, 2 , 3 and is the most widely used neurological assessment tool in studies of adults with psychotic disorders. The NES may therefore be well suited to the study of adolescents with these conditions.

We undertook the present study to investigate adolescent psychotic disorders from a neurodevelopmental perspective using structured psychiatric diagnostic interviews, the NES, and standardized measures of cognition. The overarching hypothesis of this study is that psychosis is only one of several manifestations of aberrant neurodevelopment among adolescents with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder with psychotic features. Specific study hypotheses included: 1) adolescents with psychosis demonstrate a greater frequency and severity of neurological signs on the NES than healthy comparison subjects of a similar age; 2) adolescents with psychosis perform more poorly on standardized cognitive tests (full-scale, verbal, and performance IQ) than healthy comparison subjects of a similar age; 3) the severity of neurological dysfunction on the NES is independent of the severity of cognitive impairment; 4) adolescents with psychosis will demonstrate a failure of age-expected neurological maturation on the NES; and 5) group membership (psychotic versus nonpsychotic) is predicted by NES score and full-scale IQ.

METHOD

After complete description of the study to the subjects and their legal guardians, we obtained written informed consent for study participation from the legal guardian and assent from the subjects in accordance with the policies and procedures of the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Subjects

Nineteen subjects with psychosis ages 9 to 17 years (six female) with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder with psychotic features were recruited via referrals from child psychiatrists, mental health agencies, and mental health advocacy organizations in the Denver, Colo., metropolitan area, and through advertisements in this locale. Sixteen adolescents of similar age (five female) with no personal or family history of mental illness or neurological disease were similarly recruited and served as comparison subjects.

General Clinical Assessment

Two of the investigators (D.B.A. and M.L.R.) performed general clinical assessments inclusive of developmental, medical, surgical, neurological, psychiatric, and substance histories, and also assessment of pubertal status using the Pubertal Development Scale. 9 Psychotropic medication use was recorded and categorized as: antipsychotics; lithium in any formulation; anticonvulsant mood-stabilizers; antidepressants (all classes); stimulants; and benzodiazepines.

Psychiatric Diagnoses

We administered the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL) 10 under the supervision of one investigator (M.L.R.). A DSM-based clinical interview was performed by a second investigator (D.B.A.). These assessments were used to arrive at a consensus-based study diagnosis by the lead investigators (M.L.R., D.B.A., D.C.R.) which were completed without consideration of neurological and cognitive assessment findings.

Neurological Assessment

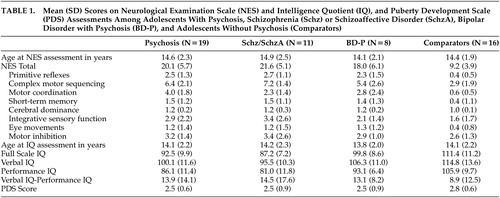

Physical examinations, elemental neurological examinations, and examinations for subtle neurological signs using the NES 2 were performed by a single investigator (D.B.A.). This investigator remained blind to K-SADS-PL diagnoses (and hence consensus-based study diagnoses) until the neurological assessments were completed and scored. NES findings were categorized into eight domains of neurological function ( Table 1 ).

|

Cognitive Assessment

A trained professional research assistant blinded to study diagnosis performed cognitive assessments. Assessment of cognition was performed using the WAIS, 3rd edition (WAIS-III) 11 or WISC, 3rd edition (WISC-III) 12 as appropriate for age. Some participants (three subjects with psychosis, two comparison subjects) were administered the 4-subtest version of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI). 13 Dependent variables derived from the Wechsler scales included full scale (FS) IQ, verbal (V) IQ, and performance (P) IQ, which were available from all of these assessments.

Inclusion Criteria

Subjects with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder with psychosis and no current or past diagnoses of alcohol or substance abuse/dependence, no history or examination findings suggestive of neurological (including traumatic brain injury or epilepsy) or developmental disorders, and no current major medical illness were included. Comparison subjects were included if their evaluations revealed no personal or family history of mental illness or neurological disease.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using Statistica 6.1 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, Okla.). Student’s t tests were used to test the hypothesis that NES scores are higher and IQ scores are lower among adolescents with psychosis than among comparison subjects. A one-sided test for differences between proportions was used to test the hypothesis that subjects with psychosis demonstrate a higher frequency of neurological subtle signs than healthy comparison subjects. Separate one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were employed to test for differences in NES and IQ scores between diagnostic groups (schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder versus bipolar disorder with psychotic features versus never mentally ill). We employed within-group Pearson’s product-moment correlations to test the hypothesis that adolescents with psychosis demonstrate a failure of age-expected neurological maturation on the NES, and to investigate the relationship between NES scores and VIQ, PIQ, and FSIQ scores. We performed binomial logistic regression analysis to examine whether group membership (psychotic versus nonpsychotic) is predicted by total NES and FSIQ. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was used to determine whether diagnosis (schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder versus bipolar disorder with psychotic features versus never mentally ill) is predicted by total NES and FSIQ. Fisher’s exact test was used to examine differences in the proportion of subjects treated with each of the classes of psychotropic medications described above. Additionally, an exploratory analysis using simple linear regression was employed to investigate whether total NES, FSIQ, VIQ, and PIQ scores predicted psychotropic medication treatment status (i.e., treatment versus no treatment) among subjects with psychosis.

RESULTS

The psychotic group (N=19) consisted of seven subjects with schizophrenia (one female), four subjects with schizoaffective disorder (one female), and eight subjects with bipolar disorder with psychotic features (four females). All subjects with bipolar disorder with psychotic features were euthymic (i.e., not in a manic, hypomanic, manic, or mixed episode and also not psychotic) at the time of study assessments. The mean age of onset for first psychiatric diagnosis in the psychotic group was 6.9 (SD=2.5) years (range=4 to 11 years) and included attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (42.1%), schizophrenia (10.5%), bipolar disorder (type unspecified or “not otherwise specified,” 31.6%), “aggressiveness” (5.3%), and no formal diagnosis (10.5%). The mean age of onset for study diagnosis was 9.7 (SD=2.8) years (range=4 to 13 years).

Among the psychotic subjects, 31.6% had a history of maternal drug use during pregnancy, including exposure to stimulants (21.1%), alcohol (21.1%), and nicotine (5.3%), alone or in combination, and 16 of 19 subjects (84.2%) had a history of treatment with stimulant medications prior to or since the onset of study diagnosis. At the time of NES assessment, medications used among subjects with psychosis included antipsychotics (84.2%), lithium in any formulation (36.8%), anticonvulsant mood-stabilizers (42.1%), antidepressants (36.8%), stimulants (31.6%), and benzodiazepines (21.1%). At the time of IQ assessment, medications used among subjects with psychosis included antipsychotics (78.9%), lithium in any formulation (42.1%), anticonvulsant mood-stabilizers (47.4%), antidepressants (42.1%), stimulants (36.8%), and benzodiazepines (15.8%). Subjects with bipolar disorder with psychotic features differed from those with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder with respect to the frequency of treatment with lithium (75% versus 18%, Fisher’s exact p<0.03) and anticonvulsant mood-stabilizers (88% versus 18%, Fisher’s exact p<0.005).

There was no effect of diagnosis on Pubertal Development Scale (PDS) scores (F=0.6, df=2.32, p=0.57). Post-hoc comparison using Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test for unequal sample sizes demonstrated no differences in PDS scores between diagnostic subgroups.

Comparison of NES Scores Between Groups

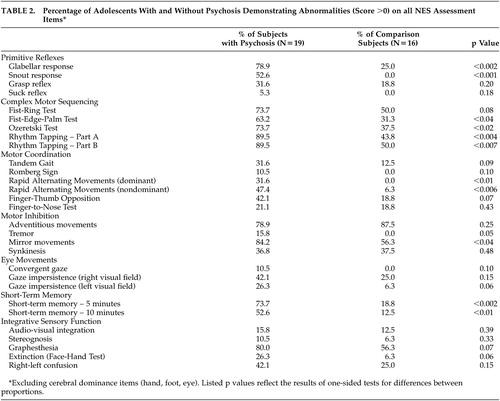

Total NES scores were significantly higher among subjects with psychosis than among comparison subjects (t=6.5, p<0.001). There also was a significant effect of diagnosis on total NES score (F=23.2, df=2,32, p<0.001), primitive reflexes (F=19.5, df=2,32, p<0.001), complex motor sequencing (F=15.7, df=2,32, p<0.001), motor coordination (F=8.2, df=2,32, p<0.002), and short-term memory (F=3.5, df=2,32, p<0.04) scores. Post-hoc comparison using Tukey’s HSD test for unequal sample sizes demonstrated a significant difference in total NES scores between both subject groups and the comparison subjects (p<0.001 and p<0.003, respectively), but no difference between subjects with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder and subjects with bipolar disorder with psychotic features. A similar pattern was observed in post-hoc comparisons of primitive reflex, complex motor sequencing, and motor coordination scores: subjects with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder did not differ from subjects with bipolar disorder with psychotic features, but both groups differed significantly from the comparison subjects (all p<0.05). Mean total and subscale NES scores among subjects with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder with psychotic features, and the never mentally ill comparison subjects are presented in Table 2 . Item-level data on the NES for the psychosis and healthy comparison groups as well as differences using a one-sided test for difference in proportions are described in Table 1 .

|

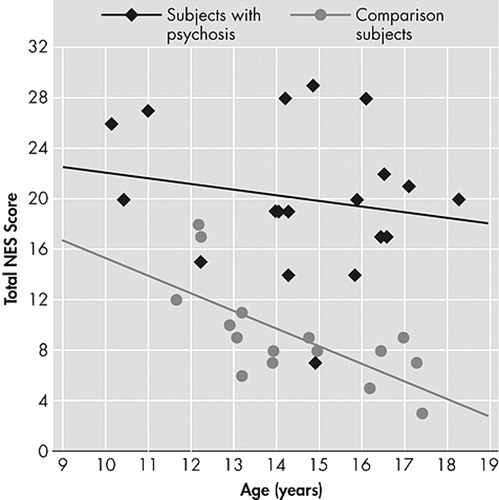

Comparison of Neurological Maturation Between Groups

There was an inverse relationship between age at time of NES assessment and total NES among the healthy comparison subjects (r=–0.68, p<0.004), but not among subjects with psychosis, collectively ( Figure 1 ) or by diagnostic group (schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder with psychotic features).

Comparison of Cognitive Assessments Between Groups

FSIQ, VIQ, and PIQ scores were significantly lower among subjects with psychosis than among comparison subjects ( Table 1 ). There was a significant effect of diagnosis on FSIQ (F=21.0, df=2,32, p<0.001), VIQ (F=8.3, df=2,32, p<0.002), and PIQ (F=21.2, df=2,32, p<0.001). Post-hoc comparison using Tukey’s HSD for unequal sample sizes demonstrated a significant difference between subjects with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder and subjects with bipolar disorder with psychotic features (p<0.04), as well as a significant difference between subjects with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder and the comparison subjects (p<0.001). We also observed a trend towards a similar difference between subjects with bipolar disorder with psychotic features and the comparison subjects (p=0.05). Post-hoc comparison of VIQ scores demonstrated significant differences between subjects with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder and the comparison subjects (p<0.003), but not the subjects with bipolar disorder with psychotic features. VIQ scores among subjects with bipolar disorder with psychotic features did not differ from those of the comparison subjects. However, PIQ scores were lower among subjects with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder than among subjects with bipolar disorder with psychotic features (p<0.05) and the comparison subjects (p<0.0002), and PIQ scores were lower among subjects with bipolar disorder with psychotic features than among comparison subjects (p<0.04).

Relationships Between Neurological and Cognitive Function

Total NES scores did not correlate significantly with FSIQ, VIQ, or PIQ scores among the subjects with psychosis, either collectively or by psychiatric diagnosis (schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder with psychotic features), or among the comparison subjects.

Prediction of Psychiatric Diagnosis Using Neurological and Cognitive Assessments

Binomial logistic regression demonstrated that the combination of total NES score (Wald statistic=6.9, p<0.009) and FSIQ (Wald statistic=4.2, p<0.04) correctly predicted membership in the psychotic group in 18 of 19 subjects (94.7%) and in the comparison group in 15 of 16 subjects (93.8%), yielding a log odds ratio of 5.6. Multinomial logistic regression indicated that the combination of total NES (Wald statistic=7.0, p<0.04) and FSIQ (Wald statistic=7.8, p<0.03) modeled psychiatric diagnosis well. The model correctly identified schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder in 10 of 11 cases (91.0%), with one case classified as bipolar disorder with psychotic features. The model also correctly classified five out of eight subjects with bipolar disorder with psychotic features (63.0%), with two cases misclassified as schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder and one case misclassified as never mentally ill. Finally, the model correctly classified 15 of 16 never mentally ill subjects (93.8%), with one case misclassified as bipolar disorder with psychotic features.

Relationships Between NES Scores, IQ Scores, and Treatment With Psychotropic Medications

We utilized simple linear regression to investigate whether total NES, FSIQ, PIQ, or VIQ predicted treatment status (treatment versus no treatment) with each of the classes of psychotropic medication described above. Total NES scores did not predict treatment status with any class of medication (all p>0.26). Initial analyses suggested that FSIQ predicts antipsychotic medication treatment status (adjusted R 2 =0.23, p<0.03) and that VIQ predicts antipsychotic and antidepressant medication treatment status (adjusted R 2 =0.23, p<0.03, and adjusted R 2 =0.17, p<0.05, respectively). However, these findings failed to remain significant after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

DISCUSSION

Subtle neurological signs were significantly more common and more severe among adolescents with psychosis than among similarly aged healthy comparison subjects. The neurological domains demonstrating the widest divergence between the subjects with and without psychosis included primitive reflexes, complex motor sequencing, motor coordination, and short-term memory. Total NES scores did not distinguish between subjects with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder with psychotic features, but NES scores in both groups differed significantly from those of the comparison subjects. Additionally, adolescents with psychosis failed to demonstrate age-expected reductions of NES scores.

These findings suggest that neurological dysfunction as assessed by the NES is strongly associated with the presence of psychosis, regardless of whether that psychosis is persistent or mood episode-related. Although the possibility of medication effect on neurological signs in this population may be of immediate concern, the regression analyses performed here suggest that this is an unlikely explanation for this finding. This suggestion is supported by the lack of association between NES scores and antipsychotic medication use reported elsewhere. 2 , 14 – 16

Similarly, IQ scores were lower among subjects with psychosis than among the comparison subjects. Although the mean full scale IQ for the psychosis group was within the normal ranges described for these measures, population-based studies demonstrate higher mean IQ levels (∼ 1 SD) in the Denver metropolitan region than in the Wechsler scale standardization sample. 17 The IQ scores of the psychotic adolescents in this study therefore reflect a greater departure from expected performance than might otherwise be apparent by these scores. Since deterioration of IQ in childhood-onset schizophrenia may begin up to 2 years prior to psychosis onset and stabilize within 2 years thereafter, 18 it is also possible that among the subjects with psychosis studied here, and particularly those with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder, IQ may not yet have reached its final (and possibly even lower) level.

In contrast to neurological signs, and similar to IQ findings among adults with these conditions, 19 , 20 there was a significant effect of diagnosis on IQ: scores were lowest among subjects with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder, highest among the healthy comparison subjects, and intermediate among subjects with bipolar disorder with psychotic features. Simple logistic regression did not identify a predictive relationship of FSIQ, VIQ, or PIQ on psychotropic medication treatment status. Although it is possible that treatment history may have influenced the IQ differences between adolescents with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder with psychotic features observed here, data adequate to the task of examining this issue statistically were not available for analyses. However, Zammit et al., 21 in a population-based sample of more than 50,000 male subjects, identified lower IQ as a risk factor for schizophrenia but not bipolar disorder. This suggests that cognitive differences between these conditions antedate both their onset and treatment with psychotropic medications. This finding supports framing IQ differences between schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder with psychotic features subjects observed in the present study as reflective of differences in neurodevelopment between these disorders rather than as a consequence of them or their treatments.

Collectively, the present findings suggest that NES and IQ reflect dependent domains in which aberrant neurodevelopment occurs among adolescents with psychosis. The utility of including neurological and cognitive assessments in the evaluation of adolescents with these conditions is evidenced by the robust prediction of group membership (psychotic versus nonpsychotic) using the combination of total NES and FSIQ scores: the discrimination between schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder and never mentally ill subjects was excellent, with no member of either group misclassified as a member of the other.

The present findings also suggest that diagnosis (i.e., disorders with persistent psychosis versus disorders with mood episode-related psychosis) may differentially influence development in these domains of neuropsychiatric function. If similar findings are observed in a larger sample of adolescent subjects with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder with psychotic features, inclusion of neurological and cognitive examinations in the clinical assessment of adolescents with psychotic disorders might improve diagnostic accuracy. However, this suggestion is necessarily speculative, as the present data indicate that NES and IQ alone are not sufficient to the task of discriminating fully between bipolar disorder with psychotic features and the other diagnostic groups included herein. The single subject in each of those two groups that was diagnostically misclassified by the model was predicted to be a member of the bipolar disorder with psychotic features group. Additionally, three of the eight subjects in the bipolar disorder with psychotic features group were diagnostically misclassified, with two identified as members of the schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder group and one identified as never mentally ill. These observations suggest that inclusion of additional factors in the model is needed to separate the bipolar disorder with psychotic features subjects from those with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder and healthy comparison subjects. Alternatively, if NES and IQ assessments are more strongly related to the neurobiology of these conditions than are phenomenological psychiatric diagnostic assessments, then cross-sectional K-SADS-PL and clinical interview-based diagnoses may not be the optimal method by which to discriminate between adolescents with these diagnoses. 22 – 24

Several limitations of the present study require consideration. It is possible that examiner knowledge of subject diagnosis may contribute to NES scores, and that examiner-subject interactions may influence the performance of subjects on both neurological and cognitive assessment measures. To the latter point, the blinded cognitive assessment by a trained technician is consistent with the methodology of other studies of this population and should minimize the potential effect of clinician bias on subject performance. The structured administration and anchored scoring methods of the NES limit the likelihood of clinician influence on subject performance, although this concern cannot be assuaged entirely. However, the magnitude of the NES differences between adolescents with and without psychosis observed here, as well as the comparability of total NES scores among subjects with and without psychosis to those reported in previous studies, 2 , 3 argue against evaluator bias as an explanation for the present findings.

The present findings also argue against psychotropic medication administration as an explanation for differences in NES and IQ scores between subjects with and without psychosis, as well as for differences in IQ scores between the psychotic subgroups. However, the absence of treatment-naïve subjects precludes a more definitive assessment of this issue.

The subject groups were not identical with respect to gender, particularly for diagnostic subgroup comparisons. Though there is no a priori rationale for suggesting an effect of gender on NES score, 2 , 14 , 25 careful matching of subjects is needed in future studies in order to more fully evaluate the effect, if any, of gender in this context.

The size of the present sample precludes evaluation of a larger number of predictor variables, including medications (individually or by class), gender, and socioeconomic status, and also reduces the power needed to investigate significant predictor variables with smaller effect sizes. Similarly, the nature of the cognitive assessments employed in the present study precludes evaluation of the relationships, if any, between specific domains of cognition and neurological dysfunction. Further studies of a larger sample of adolescents with psychotic disorders inclusive of these variables, including longitudinal studies with periodic diagnostic reassessment, symptom severity assessments, and structural or functional neuroimaging using magnetic resonance imaging, neurophysiological assessments (e.g., electroencephalography, evoked or event-related potentials, and/or magnetoencephalography) are needed to address these issues.

1 . Andreasen NC, Paradiso S, O’Leary DS: “Cognitive dysmetria” as an integrative theory of schizophrenia: a dysfunction in cortical-subcortical-cerebellar circuitry? Schizophr Bull 1998; 24:203–218Google Scholar

2 . Buchanan RW, Heinrichs DW: The neurological evaluation scale (NES): a structured instrument for the assessment of neurological signs in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 1989; 27:335–350Google Scholar

3 . Heinrichs DW, Buchanan RW: Significance and meaning of neurological signs in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:11–18Google Scholar

4 . Ross DE, Thaker GK, Buchanan RW, et al: Eye tracking disorder in schizophrenia is characterized by specific ocular motor defects and is associated with the deficit syndrome. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 42:781–796Google Scholar

5 . Keri S, Janka Z: Critical evaluation of cognitive dysfunctions as endophenotypes of schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004; 110:83–91Google Scholar

6 . Bender L: Childhood schizophrenia: clinical study of 100 schizophrenic children. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1947; 1740Google Scholar

7 . Pollack M, Goldfarb W: The face-hand test in schizophrenic children. Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1957; 77635–77642Google Scholar

8 . Karp BI, Garvey M, Jacobsen LK, et al: Abnormal neurologic maturation in adolescents with early-onset schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:118–122Google Scholar

9 . Kaiser J, Gruzelier JH: The Adolescence Scale (AS-ICSM): a tool for the retrospective assessment of puberty milestones. Acta Paediatrica 1999; Suppl:8864–8868Google Scholar

10 . Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:1065–1069Google Scholar

11 . Wechsler D: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, III, manual. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1997Google Scholar

12 . Wechsler D: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for children, III, manual. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1991Google Scholar

13 . The Psychological Corporation: The Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. San Antonio, Tex, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1999Google Scholar

14 . Arango C, Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW: Neurological signs and the heterogeneity of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:560–565Google Scholar

15 . Lawrie SM, Byrne M, Miller P, et al: Neurodevelopmental indices and the development of psychotic symptoms in subjects at high risk of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 178:524–530Google Scholar

16 . Flyckt L, Sydow O, Bjerkenstedt L, et al: Neurological signs and psychomotor performance in patients with schizophrenia, their relatives and healthy controls. Psychiatry Res 1999; 86:113–129Google Scholar

17 . Willcutt EG, Pennington BF, Olson RK, et al: Neuropsychological analyses of comorbidity between reading disability and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: in search of the common deficit. Dev Neuropsychol 2005; 27:35–78Google Scholar

18 . Gochman PA, Greenstein D, Sporn A, et al: IQ stabilization in childhood-onset schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2005; 77:271–277Google Scholar

19 . Seidman LJ, Kremen WS, Koren D, et al: A comparative profile analysis of neuropsychological functioning in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar psychoses. Schizophr Res 2002; 53:31–44Google Scholar

20 . Hobart MP, Goldberg R, Bartko JJ, et al: Repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status as a screening test in schizophrenia, II: convergent/discriminant validity and diagnostic group comparisons. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1951–1957Google Scholar

21 . Zammit S, Allebeck P, David AS, et al: A longitudinal study of premorbid IQ score and risk of developing schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe depression, and other nonaffective psychoses. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:354–360Google Scholar

22 . McKenna K, Gordon CT, Lenane M, et al: Looking for childhood-onset schizophrenia: the first 71 cases screened. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:636–644Google Scholar

23 . Nicolson R, Lenane M, Brookner F, et al: Children and adolescents with psychotic disorder not otherwise specified: a 2- to 8-year follow-up study. Compr Psychiatry 2001; 42:319–325Google Scholar

24 . Stayer C, Sporn A, Gogtay N, et al: Looking for childhood schizophrenia: case series of false positives. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004; 43:1026–1029Google Scholar

25 . Arango C, Bartko JJ, Gold JM, et al: Prediction of neuropsychological performance by neurological signs in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1349–1357Google Scholar