Evaluating Patients With Suspected Nonepileptic Psychogenic Seizures

Studies on the prevalence of PNES show variable results: from 5% to 33% of outpatients followed for epilepsy and from 10% to 58% of patients hospitalized for evaluation of refractory epilepsy present PNES. 1 – 5 The prevalence in the overall population is estimated between 2/100,000 and 33/100,000. 5 In the few epidemiological studies on this topic, it was shown that the annual incidence in the general population is 1.4/100,000 to 3/100,000. 6 , 7 According to Gates, 8 such diverse results may be explained by different methodological procedures for the diagnosis of PNES.

Since the 1980s, knowledge of PNES has increased as a result of the widespread use of intensive video-electroencephalographic monitoring (VEEG), currently considered the “gold standard” for proper diagnosis. 9 , 10

This study presents the results of the evaluation of 26 patients with suspected PNES, who were referred to prolonged intensive VEEG in an epilepsy diagnostic center at the University of São Paulo, Brazil.

METHODS

From 2003 to 2006, 98 patients underwent prolonged intensive VEEG monitoring in the Clinical Neurophysiology Laboratory of the Institute of Psychiatry of the University of São Paulo, Brazil. Out of these, a total of 26 patients were evaluated for suspected PNES. These patients were hospitalized in the VEEG unit for variable periods, during which behavior and EEG activity were simultaneously registered to observe and identify phenomena reported as seizures. Equipment used was digital Biologic Systems Corp., with Ceegraph PTI software (version 6.72.06). Electrodes were positioned according to the 10–20 international system, with additional zygomatic and ECG electrodes. Initially, basal recordings were obtained (awake and asleep), including activation procedures (hyperventilation and photostimulation), with full antiepileptic drug dosage.

In all patients, the following sequential protocol for PNES induction was carried out: simple suggestion, suggestion interview, hypnotic or posthypnotic suggestion, and placebo (saline solution) infusion. This protocol was interrupted as soon as a PNES occurred.

After this procedure, antiepileptic drugs were tapered off and VEEG monitoring was maintained for periods considered long enough for proper diagnosis. On average, patients were hospitalized for 3 weeks (range from 1 week to 6 weeks). Such prolonged monitoring periods aimed to verify the possible occurrence of epileptiform discharges or of late epileptic seizures after complete drug withdrawal.

A suspected event occurring during prolonged monitoring was defined as an epileptic seizure when accompanied by unequivocal epileptiform patterns or discharges before, during, or after its occurrence; otherwise it was defined as a psychogenic nonepileptic seizure (PNES).

As some patients may, in extreme situations such as in prolonged intensive VEEG monitoring, present isolated PNES, 11 all registered events were analyzed and shown to a person close to the patient to confirm that these were the same events as those presented in the patient’s daily life. We considered a diagnosis of PNES disorder only if the presence of PNES was validated by this procedure.

Epilepsy was defined as present when the patient presented epileptic seizure during VEEG monitoring, or if unequivocal interictal epileptiform discharges (sharp waves, spikes, or spike-wave complexes) occurred and were validated by consistent information obtained from the patient or a close person. EEG activity of uncertain clinical significance was not considered as epileptiform.

For each patient, the following diagnoses were considered:

| 1. | Epilepsy: absence of current diagnosis of epilepsy, epilepsy in remission, epilepsy in remission under treatment, and active, moderate, or severe epilepsy. Diagnoses of epileptic seizure and epileptic syndromes were defined according to International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE ) classification. 12 , 13 | ||||

| 2. | PNES disorder: absence of current diagnosis of PNES disorder, PNES disorder in remission, PNES disorder in remission under treatment, and active, moderate, or severe PNES disorder. Psychiatric disorders presenting as PNES disorder were defined according to DSM-IV. | ||||

| 3. | For both diagnoses (epilepsy and PNES disorder), the following levels of confidence were ascribed: presumed, probable, or definite. | ||||

| 4. | Psychiatric comorbidities, eventually related to epilepsy, PNES disorder, or both, were defined according to DSM-IV. | ||||

All patients underwent neurological, psychiatric, neuroimaging (magnetic resonance, interictal, and eventually ictal SPECT), and neuropsychological evaluations. Diagnoses were confirmed and communicated to the patients who were then referred for proper treatments.

Psychiatric evaluations were made up of open clinical interviews with one of three psychiatrists (JGN, MAVB, or RLM) who had comprehensive training in the neuropsychiatry of epilepsy. All cases were revised by the three interviewers to reach a diagnostic consensus. Neurological evaluations were carried out by an experienced epileptologist trained in VEEG monitoring (LAF).

Patients were divided into three groups: PNES disorder group (patients who presented PNES during VEEG monitoring, evidence of validated PNES disorder, and no evidence of epilepsy); PNES disorder/epilepsy group (patients who presented PNES during VEEG monitoring, evidence of PNES disorder, and diagnosed epilepsy); and epilepsy group (patients who did not present PNES during VEEG monitoring and had confirmed epilepsy).

RESULTS

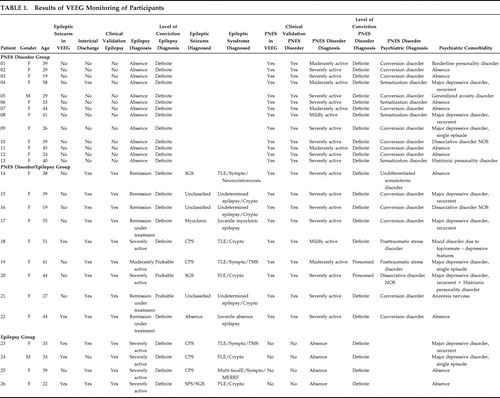

Results are presented in Table 1 . Out of 26 patients, 24 (92.3%) were female; the mean age of patients was 36 years old (range=19–58 years, median=39 years old, SD=10). No patients presented FNES during prolonged intensive VEEG monitoring or had a history of such events.

|

Thirteen patients fell into the PNES disorder group (50%); nine patients were classified as PNES disorder/epilepsy (34.6%), and four patients fell into the epilepsy group (15.4%). Therefore, the overall number of patients with PNES disorder was 22 (84.6%), and the number of patients with epilepsy was 13 (50%).

In all patients with PNES disorder, PNES were the pseudoneurological expression of the following psychiatric diagnoses: 14 patients with conversion disorder (63.6%), four with somatization disorder (18.1%), two with posttraumatic stress disorder (9%), one with undifferentiated somatoform disorder (4.5%), and one with dissociative disorder not otherwise specified (4.5%).

Fourteen out of these 26 patients presented psychiatric comorbidities (63.6%): seven depressive disorders (50%), three personality disorders (21.4%), two dissociative disorders (14.3%), one anxiety disorder (7.1%), one eating disorder, and one affective disorder caused by antiepileptic drug use.

Out of 13 patients with epilepsy, eight presented partial epilepsy (61.5%), two presented generalized epilepsy (15.4%), and three presented undetermined epilepsy (23.1%). Out of 13 patients of the PNES disorder group, 12 were female (92.3%); the mean age was 36 years old (range=19–58, median=39 years old, SD=11). Nine patients of this group (69.2%) presented conversion disorder, and four patients (30.8%) presented somatization disorder. In seven patients (54%) psychiatric comorbidities were present. In all of these cases both presence of PNES disorder and absence of epilepsy were considered as definite.

All patients in the PNES disorder/epilepsy group were female (100%); mean age was 38 years old (range=19–51, median=39 years old, SD=10). The mental disorder presenting as PNES disorder was conversion disorder in five patients (56%), posttraumatic stress disorder in two patients (22.2%), undifferentiated somatoform disorder in one patient (11.1%), and dissociative disorder not otherwise specified in one patient (11.1%). Psychiatric comorbidity was present in seven patients (77.8%). Four patients (44.4%) presented partial epilepsy, three (33.3%) undetermined epilepsy, and two (22.2%) generalized epilepsy. In three of these patients epilepsy was considered as probable because, although epileptic seizure did not occur during VEEG monitoring, and though unequivocal interictal epileptiform activity was observed, clinical validation (clinical history) was either poor or questionable. In two patients, PNES disorder was presumed because PNES were not fully validated, due to its similarity with the patient’s epileptic seizure. In six patients (67%), both diagnoses of epilepsy and PNES were considered definite.

From the four patients in the epilepsy group, three were female (75%); the mean age was 32 years old (range=22–39, median=34 years old, SD=7). Two patients (50%) presented psychiatric comorbidities. All presented partial epilepsy (100%). Absence of PNES disorder and presence of epilepsy were considered definite in all.

DISCUSSION

Female prevalence, of up to 80%, has been reported among patients with PNES. 14 , 15 In our sample this predominance was observed overall and in both the PNES disorder and PNES disorder/epilepsy groups.

Absence of FNES in our sample is in accordance with other recent studies. 16 , 17 The most common cause of FNES is syncope. Acute intoxication by cocaine, movement disorders (familial myoclonia), sleep disorders, transitory ischemic attacks, and migraine are other less frequent diagnostic possibilities. 18 The most common causes of FNES are regularly investigated in specialized neurological centers and therefore do not usually represent a clinical issue in the setting of differential diagnosis by prolonged intensive VEEG monitoring.

The possibility of PNES is usually considered when the patient presents one of the following: total absence of therapeutic response to antiepileptic drugs; loss of response (therapeutic failure) to antiepileptic drugs; paradoxical responses to antiepileptic drugs (worsening or unexpected responses); atypical, multiple, or inconsistent seizures; and seizures produced by evident and specific emotional stress factors with a close temporal relation. 19 The previous features are particularly important if the patient presents normal ancillary exams (interictal routine EEGs and neuroimaging studies, such as CT, MRI, and SPECT). 20 , 21 In such situations an attentive clinician may consider a referral to a center specialized in differential diagnosis and intensive VEEG monitoring. In 22 out of 26 patients who were referred for diagnostic investigation of suspected PNES, this hypothesis was confirmed. Therefore, we may assert that, for this sample, suspected diagnosis raised by a neurologist presented a positive predictive value of 84.6% for PNES. Such a high predictive value points to the need for a comprehensive investigation, since a failed diagnosis of PNES may be extremely damaging. Martin et al. 22 estimated that the lifetime cost for diagnostic tests, procedures, and treatments for a person with PNES would be around $100,000. They also calculated that from $100–$900 million is spent yearly caring for the PNES population in the United States. Several studies suggest that early diagnosis and adequate treatment of PNES may lead to remission in 19%–52% or to improvement in 75%–95%, meaning a considerable reduction of health system use and corresponding costs. 22 – 25 Moreover, PNES may lead to severe social and psychological consequences. Patients with PNES and their family members may be confronted with the same issues as patients with epilepsy: stigmatization, underschooling, unemployment, difficult interpersonal relationships, and social exclusion. 26 From the medical point of view, patients are unnecessarily exposed to iatrogenic procedures, such as the use of high doses of antiepileptic drugs, venous punctures, and endotracheal intubation. 27 , 28 Comorbidity with depressive and anxiety disorders is high, and the quality of life of these patients may be even worse than that of patients with refractory epilepsy. 17 , 23 , 29

However, since 13 out of our 26 patients referred for suspected PNES also had a final diagnosis of epilepsy, we may assert that a diagnosis of suspected PNES by neurologists has a negative predictive value for epilepsy of only 50%. Omission of a diagnosis of epilepsy in patients with suspected PNES may be highly damaging, since they are eventually advised to withdraw antiepileptic drugs and to limit their demand on medical emergency facilities (to reduce levels of iatrogenic procedures and costs as well as customizing their treatment to a condition of psychogenic nature). 30 – 32 Wyler et al. 33 dramatically point out the possible consequences of these procedures in their report of a 15-year-old girl whose death was caused by an epileptic seizure after she was discharged from a prolonged monitoring unit with a diagnosis of PNES and withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs. Therefore, in the presence of suspected PNES, one should not underestimate the importance of a detailed investigation for the exclusion of epilepsy.

Out of the 13 patients with a final diagnosis of epilepsy, four belonged to the epilepsy group (31%) and nine belonged to the PNES disorder/epilepsy group (69.2%). After an investigative process, patients with suspected PNES may also receive a diagnosis of epilepsy. However, most of them present both associated conditions. One of the most controversial clinical situations is the association of epilepsy and PNES. It is estimated that from 10%–73% of patients with PNES also present epilepsy. 3 , 17 , 34 A study carried out in Iceland found an association of up to 50%. 6 In our study such an association was found in nine patients (41%), a high level, but similar to that found by other authors. The causes of this finding are still unknown. In effect, these patients represent the most complex diagnostic challenge. In the PNES disorder group, absence of epilepsy was considered definite. We also had total conviction of the presence of epilepsy and absence of PNES disorder in all patients in the epilepsy group. However, in the PNES/epilepsy group, three patients had a less than definite diagnosis; epilepsy was considered probable in three patients (unequivocal interictal epileptiform activity in the absence of epileptic seizure during VEEG, but similar features between PNES and epileptic seizure semiology or disease course), and PNES were presumed in two patients (similar semiology of PNES and epileptic seizure).

Although the differential diagnoses of PNES include an ample series of psychopathological problems, from the practical point of view patients that present either episodes of impaired consciousness or motor/sensory manifestations as symptoms of pseudoneurological disorders are those with a greater chance of misguiding the physician’s reasoning, leading to specialized diagnostic procedures. These manifestations may be intentionally forged, as in factitious disorders and malingering, or not intentionally created (unconscious production) such as in mental disorders with dissociative or conversion symptoms. In all patients in our series, PNES were the pseudoneurological presentation of dissociative or conversion symptoms. In none of our patients was any other psychiatric symptom presented as PNES. These patients may present conversion disorders, somatization or undifferentiated somatoform disorder, dissociative disorder not otherwise specified, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric comorbidities were frequent in our series of patients with PNES—mostly depressive disorders—as observed in other studies. 35 , 36

In conclusion, our findings suggest that dissociative and conversion PNES are commonly observed, representing the pseudoneurological manifestation of a group of mental disorders that share these symptoms. Also, a diagnosis of suspected PNES when raised by clinical neurologists presents a high positive predictive value for PNES disorder, but low negative predictive value for epilepsy. This may be explained by frequent comorbidity between PNES disorder and epilepsy and by the elevated prevalence of epilepsy in patients with PNES disorder.

1. Benbadis SR, Lancman ME, King LM, et al: Preictal pseudosleep: a new finding in psychogenic seizures. Neurology 1996; 47:63–67Google Scholar

2. Arnold LM, Pritivera MD: Psychopathology and trauma in epileptic and psychogenic seizure patients. Psychosomatics 1996; 37:438–443Google Scholar

3. Bowman ES: Pseudoseizures. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1998; 21:649–657Google Scholar

4. Sirven JL, Glosser DS: Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: theoretic and clinical considerations. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1998; 11:225–235Google Scholar

5. Benbadis SR, Hauser AW: An estimate of the prevalence of psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Seizures 2000; 9:280–281Google Scholar

6. Sigurdardorttir KR, Olafsson E: Incidence of psychogenic seizures in adults: a population-based study in Iceland. Epilepsia 1998; 39:749–752Google Scholar

7. Szaflarski JP, Ficker DM, Cahill WT, et al: Four-year incidence of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures in adults in Hamilton County, Ohio. Neurology 2000; 55:1561–1563Google Scholar

8. Gates JR. Epidemiology and classification of non-epileptic events, in Non-Epileptic Seizures, 2nd ed. Edited by Gates JR, Rowan AJ. Boston, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2000, pp 3–14Google Scholar

9. Cragar DE, Berry DT, Fakhoury TA, et al: A review of diagnostic techniques in the differential diagnosis of epileptic and nonepileptic seizures. Neuropsychol Rev 2002; 12:31–64Google Scholar

10. LaFrance WC, Devinsky O: The treatment of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: historical perspectives and future directions. Epilepsia 2004; 45:15–21Google Scholar

11. French J: The use of suggestion as a provocative test in the diagnosis of psychogenic non-epileptic seizures, in Non-Epileptic Seizures. Edited by Gates JR, Rowan AJ. Boston, Butterworth-Heinemann, 1993, pp 101–109Google Scholar

12. Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy: Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. Epilepsia 1981; 22:489–501Google Scholar

13. Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy: Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Epilepsia 1989; 30:389–399Google Scholar

14. Lesser RP: Psychogenic seizures. Neurology 1996; 46:1499–1507Google Scholar

15. Griffith JL: Pseudoseizures: evaluation and treatment. Medscape Mental Health [serial online] 1997; 2. Available at http://www.medscape.com/Medscape/psychiatry/journal/1997/v02.n04/mh3094.griffith/mh 3094.griffith.htmlGoogle Scholar

16. Thomson LR: Nonepileptic seizures: avoid misdiagnosis and long-term morbidity. Medscape Mental Health [serial online] 1998; 8. Available at www.medscape.com/CPG/ClinReviews/1998/v08.n03/c0./c0803.02.thom.htmGoogle Scholar

17. Kurcgant D, Marchetti RL, Marques AH, et al: Crises pseudoepilépticas–diagnóstico diferencial. BJECN 2000; 6:13–18Google Scholar

18. Gates JR, Ramani V, Whalen S, et al: Ictal characteristics of pseudoseizures. Arch Neurol 1985; 42:1183–1187Google Scholar

19. Rowan AJ: Diagnosis of non-epileptic seizures, in Non-Epileptic Seizures, 2nd ed. Edited by Gates JR, Rowan AJ. Boston, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2000, pp 15–30Google Scholar

20. Davis BJ: Predicting nonepileptic seizures utilizing seizure frequency, EEG, and response to medication. Eur Neurol 2004; 51:153–156Google Scholar

21. Dworetzky BA, Strahonja-Packard A, Shanahan CW, et al: Characteristics of male veterans with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia 2005; 46:1418–1422Google Scholar

22. Martin RC, Gilliam FG, Kilgore M, et al: Improved health care resource utilization following video-EEG-confirmed diagnosis of nonepileptic psychogenic seizures. Seizure 1998; 7:385–390Google Scholar

23. Ettinger AB, Devinsky O, Weisbrot DM, et al: A comprehensive profile of clinical, psychiatric, and psychosocial characteristics of patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia 1999; 40:1292–1298Google Scholar

24. Walczak TS, Papacostas S, Williams DT, et al: Outcome after diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia 1995; 36:1131–1137Google Scholar

25. Silva W, Giagante B, Saizar R, et al: Clinical features and prognosis of psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Epilepsia 1991; 40:263Google Scholar

26. Betts T, Duffy N: Treatment of non-epileptic attack disorder (pseudoseizures) in the community, in Pseudo-Epileptic Seizures. Bristol, Pa, Wrightson Biomed Pub, 1993, pp 109–121Google Scholar

27. Niedermeyer E: The Epilepsies: Diagnosis and Management. Baltimore, Urban & Schwarzwnberg, 1990, pp 251–256Google Scholar

28. Lesley MA, Pritivera MD: Psychopathology and trauma in epileptic and psychogenic patients. Psychosomatics 1996; 37:438–443Google Scholar

29. Szaflarski JP, Hughes C, Szaflarski M, et al: Quality of life in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia 2003; 44:236–242Google Scholar

30. Oto M, Espie C, Pelosi A, et al: The safety of antiepileptic drug withdrawal in patients with non-epileptic seizures. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005; 76:1682–1685Google Scholar

31. LaFrance WC Jr, Benbadis SR: Avoiding the costs of unrecognized psychological nonepileptic seizures. Neurology 2006; 66:1620–1621Google Scholar

32. McDade G, Brown SW: Non-epileptic seizures: management and predictive factors of outcome. Seizure 1992; 1:7–10Google Scholar

33. Wyler AR, Herman BP, Blumer D, et al: Pseudo-pseudo-epileptic seizures, in Non-Epileptic Seizures. Edited by Gates JR, Rowan AJ. Boston, Butterworth-Heinemann, 1993, pp 73–84Google Scholar

34. Benbadis SR, Agrawal V, Tatum WO IV: How many patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures also have epilepsy? Neurology 2001; 57:915–917Google Scholar

35. Bowman ES, Markand ON: Psychodynamics and psychiatric diagnoses of pseudoseizure subjects. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:57–63Google Scholar

36. Bowman ES: Psychopathology and outcome in pseudoseizures, in Psychiatric Issues in Epilepsy: A Practical Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment. Edited by Ettinger AB, Kanner AM. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001, pp 355–377Google Scholar