Open-Lip Schizencephaly Associated With Bipolar Disorder in a Young Man Exposed in Utero to the Chernobyl Disaster

Case Report

In May 2005, a 19-year-old boy affected by schizencephaly presented with reduced sleep, visual and auditory hallucinations, irritability, aggressiveness, and psychomotor agitation. He was hospitalized and administered olanzapine, 20 mg/day and lorazepam, 5 mg/day. Acute psychopathology remitted in 5 days. Hospitalization at age 16 had occurred for generalized seizures and was treated with valproate sodium. One month before psychiatric admission, he had deliberately discontinued valproate.

The patient was born post-term in a small city near Bucharest, Romania, in June 1986, 2 months after the Chernobyl nuclear plant accident. He had learning problems that led to educational failure at age 13, when he was diagnosed with schizencephaly.

Physical examination revealed left hemiparesis, strabismus, nystagmus, and reduced vision in his right eye.

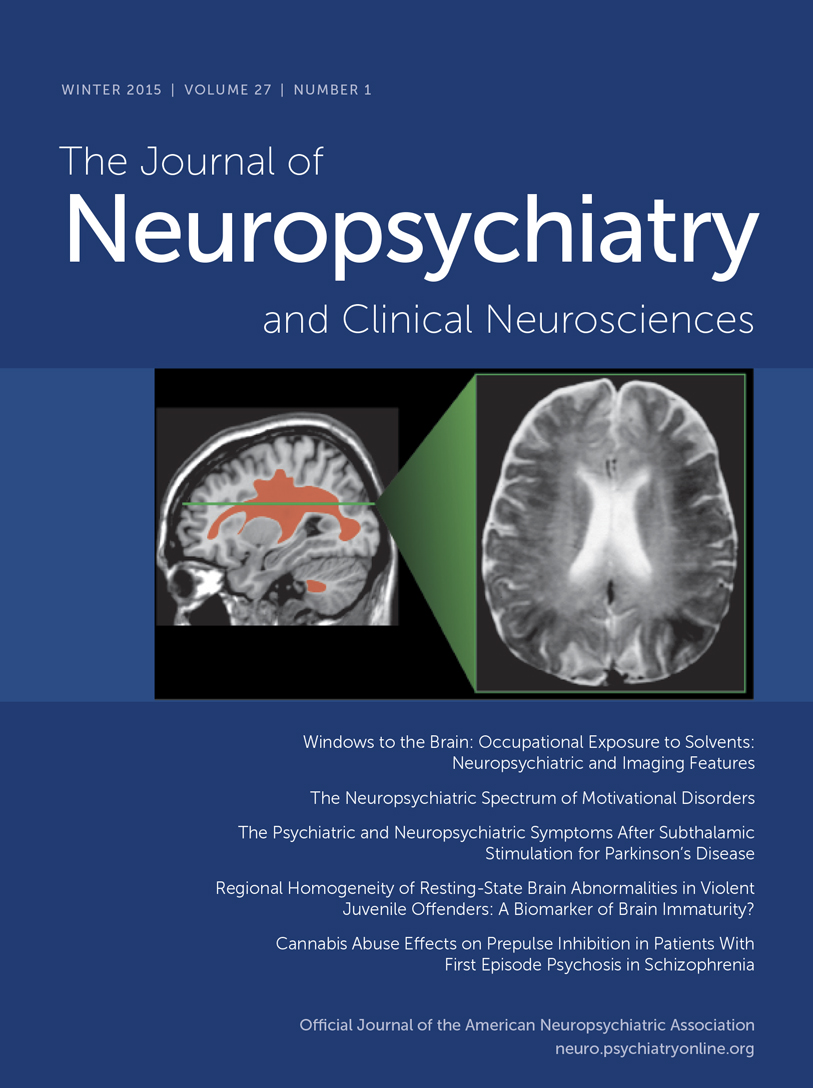

Neuropsychological assessment showed executive dysfunction, but average intellectual functioning; age-adjusted IQ score, assessed in Italian, was 97. His EEG showed nonspecific slow-wave activity in right temporal and parietal cortices and some epileptiform discharges of moderate entity. Brain MRI showed open-lip schizencephaly with absence of considerable portions of the right frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes (Figure 1, Figure 2). He was discharged with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder and a prescription of 10 mg olanzapine/day. He has been followed up on a monthly basis since then. He had no more psychotic relapses, but manifested a depressive episode and intermittent depressive symptoms. Treatment was left unchanged. He signed free, informed consent for publication of his case.

Discussion

Five closed-lip schizencephaly cases with psychiatric symptoms have been described, but this is the first description of open-cleft schizencephaly with mania. Mood elevation, secondary to deliberate valproate discontinuation, could have left the patient vulnerable to manic switch. This would be in line with Carran et al.,2 who observed 75% of patients developing manic episodes in the postoperative period after right temporal lobectomy. Hence, mania could be associated with hyperactivity of the left temporal lobe, a region mainly related to positive emotions, unopposed by the activity of the right temporal lobe, the site of negative emotions.

Visual and auditory hallucinations could be related to altered right parieto-occipital and left temporo-parietal connections, respectively.3

The role of fetal prenatal exposure to radiation after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster is unclear. Radiation-induced neurological intrauterine damage peaks between Weeks 8–15 and 16–25 of pregnancy, when neuronal migration and differentiation occur, respectively. Since our patient was exposed to the Chernobyl disaster after the 28th week, it is unlikely that radiation could account for the anatomic abnormality. However, people exposed in utero to Chernobyl radiation subsequently developed psychiatric syndromes.4,5

1. : Schizencephaly: clinical spectrum, epilepsy, and pathogenesis. J Child Neurol 2005; 20:313–318Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. : Mania following temporal lobectomy. Neurology 2003; 61:770–774Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. : Auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia are associated with reduced functional connectivity of the temporo-parietal area. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 67:912–918Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. : Disrupted development of the dominant hemisphere following prenatal irradiation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2008; 20:274–291Link, Google Scholar

5. : Chernobyl exposure as stressor during pregnancy and behaviour in adolescent offspring. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2007; 116:438–446Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar