Bifrontal Hypermetabolism on Brain FDG-PET in a Case of C9orf72-Related Behavioral Variant of Frontotemporal Dementia

Behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) is a neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by progressive degeneration of the frontotemporal lobes. It causes a heterogeneous clinical picture of behavioral and cognitive symptoms, including disinhibition, apathy, compulsive behaviors, hyperorality, and executive dysfunction or social cognitive deficits.1 The corresponding neuroimaging findings in bvFTD are frontal or anterior temporal atrophy on MRI or computerized tomography (CT) as well as hypometabolism in the aforementioned regions on fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan.1 Different genetic mutations have been identified as causing bvFTD, the most common of which is the C9orf72 mutation. C9orf72 is a GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat expansion on chromosome 9 open reading frame 72, which causes a pathogenic accumulation of transactive response DNA binding protein-43 (TDP-43).2C9orf72 is often associated with atypical presentations and neuroimaging. For example, psychiatric presentations—especially psychosis and late-onset mania3—combined features of bvFTD and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, slowly progressive cases,4 and a higher frequency of normal MRI and PET scans5–7 are all well documented in C9orf72. We present the first case, to our knowledge, of C9orf72-related bvFTD with paradoxically increased bifrontal metabolism on FDG-PET.

Case Report

“Mr. V” is a 68-year-old married, retired delivery man with no significant past medical history. He was not taking any regular medications. His past psychiatric history was notable for consuming approximately 20 drinks of alcohol daily for many years, although recently he had become completely abstinent after an accident. Additionally, he was briefly admitted to a psychiatric ward in his twenties for what he and his wife described as a cannabis-induced “psychosis” with grandiose delusions. Details regarding this admission remained unclear; however, the patient had no subsequent psychiatric follow-up and never took any psychiatric medications. He had no family history of any psychiatric disorders, early-onset dementias, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or other neurodegenerative disease, and his four siblings and one daughter were all in good health.

The patient was initially seen in a cognitive neurology clinic with a 2-year history of progressive behavioral and personality changes. He had become increasingly rigid with his daily routine, while simultaneously becoming more socially withdrawn and filling his time with nonproductive compulsive and ritualistic behaviors (for example, spending hours picking up rocks outside his home until his wife forced him to stop). He also began to neglect his personal hygiene, while exhibiting a variety of verbal stereotypies, loss of empathy, apathy, and disinhibition (such as swearing and burping in public and approaching strangers). His constellation of symptoms at his first presentation further included increased sugar intake, rapid ingestion of meals to the point of choking (without dysphagia), and a preoccupation with his saliva, initially mitigated by compulsive gum chewing. He exhibited no focal neurological symptoms and no changes in memory, language, or orientation, and he had no recent falls.

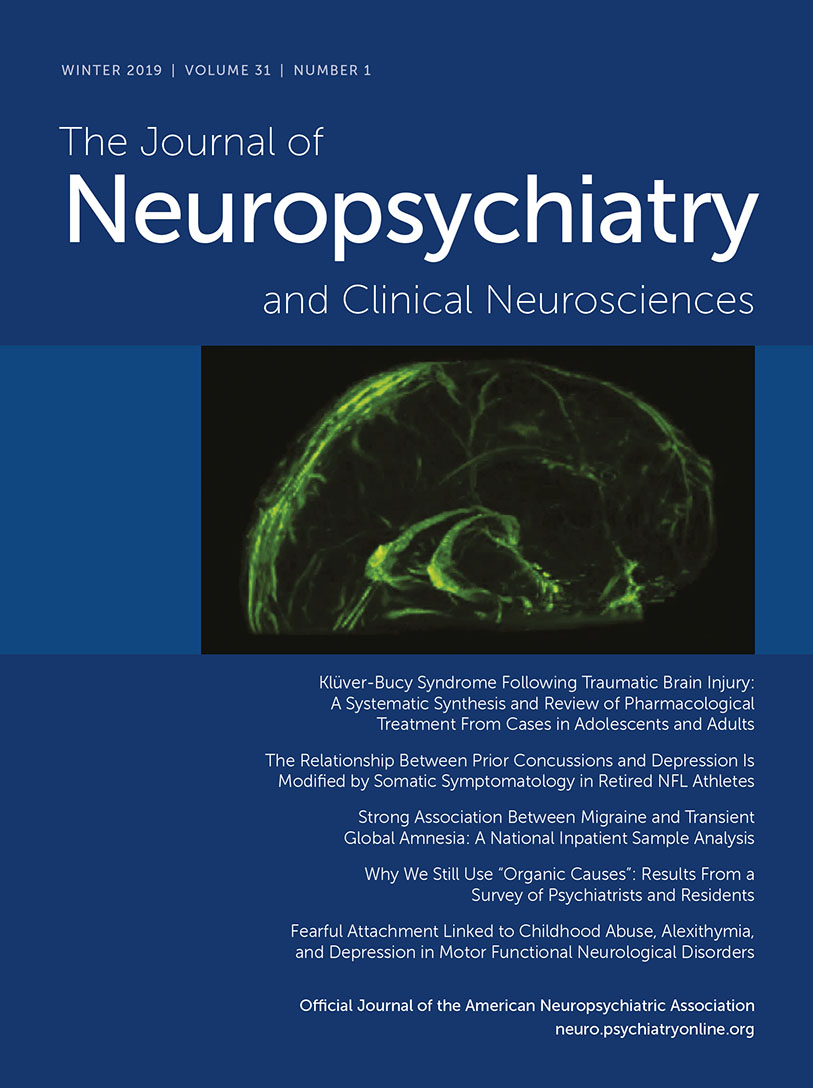

In terms of initial cognitive testing, he scored 29/30 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (z score, 0.6988), 28/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (z score, 1.189), 16/18 on the Frontal Assessment Battery (z score, –0.2510), and 36/72 on the Frontal Behavioral Inventory, with a score of 19 for negative behaviors and 17 for the section on disinhibition (total score clinically significant for the inventory, 3611). Investigations subsequently began with a head CT scan (due to its higher availability relative to the MRI in Quebec), which was unremarkable. Following CT, a brain FDG-PET scan was ordered (Figure 1). Surprisingly, the FDG-PET showed bifrontal hypermetabolism without any significant areas of hypometabolism. However, given the strongly suggestive clinical picture, a diagnosis of possible bvFTD was maintained despite the atypical neuroimaging. The patient was then started on citalopram (titrated up to 20 mg) for his compulsive behaviors.

FIGURE 1. Brain Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron-Emission Tomography of a Patient With Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementiaa

a Findings were reported as bifrontal hypermetabolism with no significant areas of hypometabolism, no suspicious regional deficits, and overall no evidence of any neurodegenerative process. A=anterior, P=posterior.

Paradoxically, after initiating citalopram, the patient became even more agitated. He was tried on a succession of different psychiatric medications, including second-generation antipsychotics, in an attempt to mitigate his behavioral symptoms, with minimal improvement. At this point, a consultation was made with our tertiary care neuropsychiatry clinic at the Montreal Neurological Institute.

When seen in consultation, the patient displayed signs of comorbid mania that was out of proportion to the manic-like symptoms that can be observed in bvFTD.12 He had insomnia, was overexcited and talkative, and displayed racing thoughts. Interestingly, he was also in the process of writing a lengthy book of poetry, with plans to publish it, although he had never written poetry previously. In addition to manic symptoms, he continued to exhibit symptoms of bvFTD, including prominent compulsive behaviors (e.g., sending excessive e-mails to the same people every morning) as well as both motor and verbal stereotypies (e.g., constant audible deglutition efforts and short word repetition). He also experienced general functional decline, with worsening of insight and judgement, such that his wife needed to begin managing his instrumental activities of daily living.

Further investigations at this time included a normal neurological examination and a stable score of 28/30 on the MoCA (−1 for the Trail-Making Test, Part B; –1 for being off by 1 year; z score, 1.229). Although the patient’s global score was within normal limits, cognitive screening tests (Trail-Making Test, Part B, and Luria test) were suggestive of mild executive dysfunction. A thorough panel of bloodwork, including complete blood count, electrolyte, liver function, creatinine, thyroid-stimulating hormone, vitamin B12, HIV, and syphilis testing, revealed normal and negative results. Despite the unsupportive neuroimaging, a main diagnosis of possible bvFTD was initially retained, with a superimposed diagnosis of bipolar disorder, manic episode.

In parallel to these investigations, a second opinion was obtained from a nuclear medicine specialist in dementia. When compared with a bank of normal scans, the patient’s FDG-PET was confirmed to show no areas of hypometabolism (only medial prefrontal metabolism in the lower range of normal), and atypical dorsal frontal metabolism at the higher end of normal was again reported. Additionally, there was hyperactivity in the hypothalamic-midbrain area. Brain MRI was performed approximately 3 years after the onset of the patient’s symptoms, which revealed mild to moderate diffuse cortical and cerebellar atrophy with no regional specificity.

The patient’s residual manic symptoms were ultimately stabilized with a combination of valproic acid and risperidone. However, the patient later developed dysphagia suggestive of frontotemporal dementia-amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, at which point genetic testing was performed despite an unremarkable family history. A C9orf72 repeat expansion was identified, confirming the diagnosis of definite bvFTD. An electromyogram was limited by collaboration, but results showed signs of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Discussion

C9orf72-related bvFTD can be a challenging diagnosis for clinicians, especially in cases with multiple atypical features.12C9orf72 mutations have been identified in 2%−5% of apparent sporadic bvFTD cases involving patients without family history.13 In addition, the association between C9orf72 mutation and different prodromal and comorbid psychiatric disorders, especially psychosis and mania, is well documented in the literature.3,14 Furthermore, neuroimaging is recognized as being less reliable in cases of C9orf72-related bvFTD with either normal MRI or atypical atrophy patterns.5–7 Although PET has been found to be more sensitive than structural imaging modalities, a normal PET does not rule out C9orf72-related bvFTD.5–7

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of a patient with definite bvFTD displaying increased bifrontal and subcortical metabolism on FDG-PET. From a diagnostic standpoint, there were clear manic symptoms that were not simply a misinterpretation of bvFTD features (e.g., racing thoughts, accelerated speech, grandiosity, and elated affect). These manic features were also not prodromal to the onset of bvFTD but rather comorbid (i.e., manic symptoms fluctuated throughout the course of bvFTD). It is possible that neuronal degeneration could have contributed to unmasking bipolar disorder in a patient with a possible substance-related episode in his twenties. Our original hypothesis for our patient’s surprising PET results was that the findings could perhaps be explained by the fact that in addition to bvFTD, he also presented with a separate diagnosis of mania. However, a meta-analysis of 55 studies about functional neuroimaging in bipolar disorder concluded that the mechanism of bipolar disorder entailed frontal hypoactivity and limbic hyperactivity, although it is important to consider the limitations inherent to these studies, since they are based on heterogeneous patient populations examined under varying parameters.15 This would be compatible with the hypothalamic-midbrain hyperactivity observed in our patient but not consistent with the dorsolateral bifrontal metabolism at the upper limit of normal, which makes the present case even more enigmatic. It is noteworthy that Vijverberg et al.7 demonstrated abnormal FDG-PET findings in about one-third of patients with primary psychiatric disorders in an FTD clinic.

This case highlights that clinicians should have a strong index of suspicion for a C9orf72 mutation in patients with suspected bvFTD with strong psychiatric components and normal or atypical imaging. Our case also demonstrates that unsupportive FDG-PET findings do not rule out bvFTD, even in the context of relatively advanced symptoms.

1 : Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 2011; 134:2456–2477Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 : Genetics of dementia. Lancet 2014; 383:828–840Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 : Psychiatric presentations of C9orf72 mutation: what are the diagnostic implications for clinicians? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2017; 29:195–205Link, Google Scholar

4 : Atypical, slowly progressive behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia associated with C9ORF72 hexanucleotide expansion. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012; 83:358–364Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 : Frontotemporal dementia associated with the C9ORF72 mutation: a unique clinical profile. JAMA Neurol 2014; 71:331–339Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 : The phenotype of the C9ORF72 expansion varriers according to revised criteria for bvFTD. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0131817Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 : Diagnostic accuracy of MRI and additional [18F]FDG-PET for behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia in patients with late onset b0ehavioral changes. J Alzheimers Dis 2016; 53:1287–1297Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 : A web-based normative calculator for the Uniform Data Set (UDS) neuropsychological test battery. Alzheimers Res Ther 2011; 3:32Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 : Normative Ddta for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in middle-aged and elderly Quebec-French people. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2016; 31:819–826Crossref, Google Scholar

10 : The Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB): normative values in an Italian population sample. Neurol Sci 2005; 26:108–116Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Frontal Behavioral Inventory: diagnostic criteria for frontal lobe dementia. Can J Neurol Sci 1997; 24:29–36Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 : Clinical approach to the differential diagnosis between behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and primary psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2015; 172:827–837Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 : Familial frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis associated with the C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat. Brain 2012; 135:652–655Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 : Frontotemporal dementia and psychiatric illness: emerging clinical and biological links in gene carriers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016; 24:107–116Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 : Toward a functional neuroanatomical signature of bipolar disorder: quantitative evidence from the neuroimaging literature. Psychiatry Res 2011; 193:71–79Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar