Stability of Neurological Soft Signs in Chronically Hospitalized Schizophrenic Patients

Abstract

Neurological soft signs (NSS) have been shown to be more prevalent in chronically ill and in acute or never-medicated patients with schizophrenia. If neurological soft signs are trait-like, then NSS scores should be relatively stable over time and should not be related to changes in patients' psychopathology or medication. Chronically hospitalized patients with schizophrenia were rated two or more times over a 5-year period with standard NSS and psychopathology scales. Total NSS scores were highly correlated over time, and changes in NSS scores at two time points were not significantly related to changes in psychopathology scores. Total NSS scores did not change significantly in a subsample rated when they were first treated with a traditional neuroleptic and later with an atypical neuroleptic. The findings suggest total NSS scores may have some characteristics of a trait-like feature in chronically hospitalized patients with schizophrenia.

Neurological soft signs (NSS) have been found prevalent in patients chronically ill with schizophrenia, as well as among first-episode or untreated schizophrenic patients.1–3 Reports suggest that such signs are associated with a chronic course of illness, thought disorder, negative symptoms, and a deficit state. Their relationship to treatment response is unclear. A recent open study by our group4 reported that severity of NSS correlated negatively with degree of reduction in positive symptoms in chronically hospitalized, nonresponding schizophrenic patients who were given a trial of risperidone.

On the basis of their studies and reviews, some researchers suggest that neurological signs may represent a trait characteristic of chronically ill schizophrenic patients.1,5 These researchers reported that NSS scores did not change during a 10-week trial of haloperidol or clozapine. In contrast, two studies in acute or relapsing schizophrenic patients hospitalized in primary care facilities have reported changes in NSS during a short-term course of treatment with neuroleptics.6,7 One of these studies in relapsing schizophrenic patients6 used the NSS scale of Buchanan and Heinrichs,8 and the other study7 used a self-devised, literature-based neurological soft sign scale.

We hypothesized that if NSS were a trait rather than a state characteristic in chronically hospitalized schizophrenic patients, NSS scores would show stability over time; changes in NSS scores would be unrelated to changes in psychopathology scores; NSS scores would not significantly change with a switch between typical and atypical neuroleptics; and changes in NSS scores would not be significantly related to the time interval between rating occasions.

To investigate these questions, we analyzed NSS scores in chronically hospitalized schizophrenic patients rated for their NSS and other symptoms over several years. A subsample of patients was rated when they were initially on typical neuroleptics and later when they were treated with risperidone or clozapine.

METHODS

Subjects

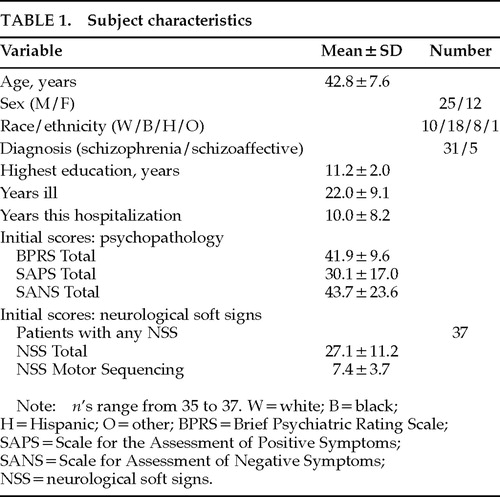

Subjects were 37 patients with a diagnosis of chronic schizophrenia or schizoaffective psychosis, by DSM-III-R criteria, who were hospitalized for more than a year at a tertiary care state hospital. Characteristics of subjects are shown in Table 1. All patients signed informed consent for participation in the research. Diagnosis was made by means of a DSM-III-R checklist, using data from the patient's chart, an interview of the patient to supplement the recorded history, and the results of psychopathology rating scales described below. Patients who had clinically significant and currently symptomatic neurological illness or who had significant drug abuse in the past 2 months were excluded from the sample.

Procedures

Patients in this report had participated in several research protocols, all of which involved evaluation of NSS as one of their procedures. Patients were evaluated for NSS with a slightly modified version of a scale proposed by Buchanan and Heinrichs.8 The modification consisted of the addition of three and the deletion of two items, based on reviews of other scales and the suggestions of a double-boarded neuropsychiatric consultant. The analysis presented in the present report uses both an NSS Total score (sum of scores on all items) and NSS component scores described in the original Buchanan and Heinrichs paper. NSS Motor Sequencing score is the sum of Fist-Ring, Fist-Edge-Palm, and Ozeretski procedures. NSS Motor Coordination score is the sum of Tandem Walk, Rapid Alternating Movements, and Finger-Thumb Opposition. NSS Sensory Integration score is the sum of Graphesthesia, Stereognosis, Two-Point Discrimination, and Right/Left Confusion.

Patients were evaluated on each occasion either by a single rater or simultaneously by two or more raters. On those rating occasions on which the patients had been evaluated for NSS by two or more raters simultaneously, the average score of all raters was used in the final analysis. Interrater reliability for total and component scores on our NSS scale, assessed by the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC)9 from joint ratings by two sets of examiners on two different series of patients, was as follows: NSS Total, 0.93, 0.99; motor sequencing subscore, 0.88, 0.96; motor coordination subscore, 0.82, 0.91; and sensory integration subscore, 0.84, 0.99.

The same patients were evaluated over several years. The mean interval between ratings was 621±520 days (range 19–1,845). All patients were evaluated on at least two occasions, and 22 patients were evaluated on three occasions. At their initial ratings, most patients were being treated with conventional neuroleptic medications. On their second or third rating occasions, some of the patients were being treated with atypical neuroleptics, risperidone, or clozapine.

Patients were evaluated for current psychiatric symptoms with several psychiatric rating scales: the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS),10 The Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS),11 and The Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS).12 (Patients with absence of symptoms on a specific item receive a score of 1 on the BPRS and 0 on the SAPS and SANS scales.) On some occasions, patients were also evaluated with the Simpson-Angus Scale or the Scale for Assessment of Movements Disorders (SAMD; described in Smith and Kadewari4). All psychopathology ratings were performed by a single rater (R.S.). All ratings were performed within 3 weeks of the neurological soft sign ratings, and most were performed within the same week.

The ratings were performed in the course of several different studies in which psychopathology scores and the neurological soft sign scores were used as some of the baseline or outcome measures. The data analysis and hypotheses examined in the present report were not specifically addressed or planned for in the original studies, in which the NSS scale was used as one of multiple measures.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) and the mixed-model regression program (MixReg),13 using correlational analysis, t-tests, and repeated-measures analyses of variance and covariance. Primary analysis was performed on the NSS Total score; NSS subscores of motor sequencing, motor coordination, and sensory integration8 were also analyzed. The stability of NSS scores over two rating occasions was evaluated by Pearson correlations. The stability of NSS scores over both two and three ratings occasions was also evaluated by intraclass correlation coefficients; for three occasions, the ICC was calculated for repeated-measures design with missing data, using the program MixReg. The relationships, on different rating occasions, of changes in NSS scores to changes in psychopathology scores and to time between ratings were evaluated by Pearson correlations. The statistical significance of differences in NSS scores in the same subjects when treated with typical and atypical neuroleptics was evaluated by paired t-tests.

The stability of individual items on the neurological soft sign scale was evaluated on a subsample of 28 subjects rated on two occasions. Each sign was evaluated as present or absent on each rating occasion. Stability was evaluated by calculation of percentage agreement (sign present or absent) and kappa.

RESULTS

This sample of patients had fairly high NSS scores, as reflected in their initial NSS total scores (Table 1). Our patients had higher mean NSS Total and component scores than patients evaluated with a similar scale in other studies (range of mean NSS total scores in these studies was 8.9 to 17.4).5,8,14 However, the range of NSS Total scores in our subjects was fairly wide (7 to 47).

NSS Total scores were highly correlated on different rating occasions of the same subject. Pearson calculations showed a highly significant correlation (r=0.83, P<0.001) between NSS Total scores rated on two different occasions (Figure 1). Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were also high (Table 2). If subjects' NSS Total scores were categorized into three groups (low<20, medium=20–31.9, high≥32), cross-tabulations showed a highly significant association of NSS Total scores on any two rating occasions (χ2, P≤0.01); in three different cross-tabulations, 62% to 67% of subjects remained in the same category and all but one of the others remained in the adjacent category.

Motor sequencing tasks and motor coordination task component scores were moderately correlated on different rating occasions (r 0.55–0.65, P<0.01; ICCs in Table 2). NSS Sensory integration subscores were much more weakly correlated on different rating occasions (r 0.33–0.56; ICCs in Table 2).

Neither the length of time between ratings nor the rater who evaluated the NSS on a specific occasion affected the variability of NSS scores. There were no consistent effects of length of time between rating occasions on extent of difference in NSS scores. There were no significant correlations between the time between successive NSS ratings and the difference in NSS score between the ratings (r 0.05–0.19). Analysis of covariance also showed no effects of time between rating occasions (covariate) on the difference between NSS scores on two occasions. Repeated-measures analysis of covariance showed no effects of differences in rater on NSS scores.

NSS scores did not appear to increase over time. Neither NSS Total nor component scores were highly correlated with the number of years ill at time of assessment (r 0.11–0.24). Overall, repeated-measures analyses of variance revealed a small decrease in mean NSS scores on successive ratings occasions, but the magnitude of mean changes was small.

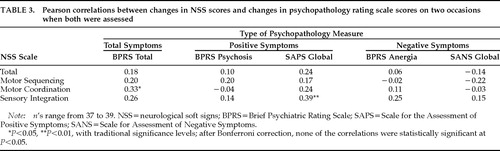

Changes in NSS scores were not related to changes in patients' symptoms. There were no consistent relationships between change in NSS scores on two occasions and changes in total psychopathology or positive or negative symptoms scores measured close to the same time. Most correlations were very low and not statistically significant (Table 3).

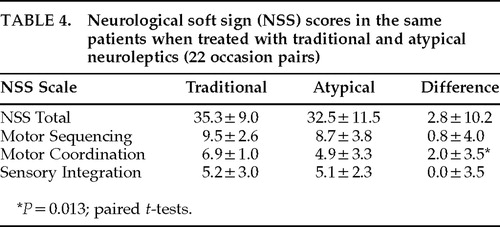

A change from a typical to an atypical neuroleptic did not consistently lead to lower NSS scores. On 22 occasion pairs in which patients originally on a typical neuroleptic were later switched to either risperidone or clozapine, there were no significant differences in NSS scores, except for the motor coordination component score, which showed a small but significant decrease (Table 4). The nonsignificant trend toward lower scores on atypical neuroleptic is consistent with the overall finding, mentioned above, of a slight decrease in NSS scores over time.

Individual NSS scale items showed large variability in their stability (Table 5). Some items showed moderately high agreement over two rating occasions, and others showed considerably lower agreement. For some items, the relatively low kappas in the face of high percentage agreement are a reflection of the marginal constraints for items in which a large majority of subjects consistently had either “present” or “absent” scores on both rating occasions.

DISCUSSION

NSS Total scores showed relatively high stability over time (as indicated by ICCs and correlation coefficients), and changes in these scores were not related to time between ratings, changes in psychopathology scores, or neuroleptic drug treatments. These findings support the idea that this measure may be relatively stable in chronically hospitalized schizophrenic patients and has some properties of a trait-like characteristic. This hypothesis agrees with the findings or suggestions of some other investigators.1,5 The NSS Total scores did not increase in severity over several years and did not significantly correlate with length of illness, suggesting that they were not progressive over the time period of the illness we evaluated. We were not able to study our patients early in their illness or compare neurological signs they currently had with those in their first or second hospitalization. It is possible that neurological signs have a more variable picture or progressive course in acute schizophrenic patients, earlier in the course of the illness, or in less chronically ill schizophrenic patients, as suggested by reports of two other investigations.6,7

Some studies have reported a high correlation of tardive dyskinesia (TD) and NSS scores,15 but this has not been universally found.16 Although most of our patients did not have prominent signs of tardive dyskinesia, we did not serially assess with the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale or another tardive dyskinesia measure. If NSS and TD scores were highly correlated and covaried consistently in our sample, this might present a confounding factor in the interpretation of the substantive significance of the stability of NSS total scores over time.

Our findings that motor sequencing and motor coordination scores showed only moderate stability, and sensory integration fairly low stability, over time suggest that NSS Total scores are a preferable measure to choose for correlational studies of long-term clinical response or other trait-like characteristics. Since individual signs showed considerable variability in their stability, they should not be relied on in predictive or correlational studies. The lower stability of many individual signs is consistent with a preliminary meeting poster on NSS item stability presented by Sanders and associates.17

An ideal trait-like characteristic would show high stability not only in total score but also in individual component subscores and item scores. Since we did not find this to be the case, it makes the interpretation of NSS as a classical trait-like characteristic more ambiguous. Although component subscores showed the same pattern of correlations with dependent variables (psychopathology scores, time between ratings) as did total score, their within-subject stability across time, as indicated by Pearson and intraclass correlation coefficients, was lower. If the subscores were uncorrelated or weakly correlated with NSS Total scores, they might represent independent factors. This might help explain the differences in stability of NSS Total and component scores across time. The psychometric properties of the NSS scale have not been extensively investigated. Whether the component subscores represent consistent independent entities is unclear. Buchanan and Heinrichs8 reported that NSS Total scores for their scale were significantly correlated with component subscores in schizophrenic patients (r 0.57–0.69, P<0.01). However, they found considerably smaller correlations among the different NSS component scores themselves (r 0.26–0.31). In our sample of chronically hospitalized schizophrenic patients, NSS Total scores were also highly correlated with the three component subscores (r=0.62–0.88, P<0.001). However, contrary to the findings of Buchanan and Heinrichs, NSS motor sequencing and motor coordination subscores also showed fairly high correlations (r 0.64–0.72, P<0.001); sensory integration scores showed a lower correlation with the other NSS component scores (r 0.28–0.46, P range 0.11–0.015). These correlations suggest that some of the component scores may not represent statistically independent factors in our patients, although a formal factor analysis scale has not been performed. Therefore, the explanation of the differences in the stability of the component scores on the basis of “independent factors” is less plausible. Alternatively, the correlations between different subscores may represent a functional interdependence between different brain areas. It is possible that the deficits represented by high neurological soft sign scores in chronic schizophrenic patients are not localized to a single brain region, but rather may represent a more general problem in interneuronal signaling. Even though patients may exhibit variable severity in specific expressions of motor or cognitive-motor function at different times, the total extent of the deficit, represented by NSS Total score, remains fairly constant. Longitudinal research of NSS over the developmental course of patients with schizophrenia who become chronically hospitalized may provide evidence to support this interpretation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Robert Gibbons, Ph.D., provided substantial help with the statistical analysis of data conducted with the MixReg program. Donald Mender, M.D., was a consultant on scale items. This work was previously presented at the VI International Congress on Schizophrenia Research, Colorado Springs, CO, April 1997.

|

|

|

|

|

FIGURE 1. Relationship of NSS Total scores measured on two occasions. Thirty-seven patients were assessed on two or three occasions. Each point represents NSS Total scores on one of these occasions versus score on another occasion. Linear regression is least square linear regression line. NSS=neurological soft signs; R= Pearson correlation coefficient.

1 Heinrichs D, Buchanan R: Significance and meaning of neurological signs in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:11–18Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Gupta S, Andreasen N, Arndt S, et al: Neurological soft signs in neuroleptic-naive and neuroleptic-treated schizophrenic patients and in normal comparison subjects. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:191–196Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Sanders RD, Keshavan MS, Schooler NR: Neurological examination abnormalities in neuroleptic-naive patients with first-break schizophrenia: preliminary results. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1231–1233Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Smith R, Kadewari R: Neurological soft signs and response to risperidone in chronic schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 40:1056–1059Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Buchanan R, Koeppl P, Brier A: Stability of neurological signs with clozapine treatment. Biol Psychiatry 1994; 36:198–200Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Scheffer R, Correnti E, Borison R, et al: Temporal stability of neurological signs in first-episode psychotic patients (abstract). Biol Psychiatry 1994; 35:715Google Scholar

7 Schroder J, Niethammer R, Geider F, et al: Neurological soft signs in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1992;6:25–30Google Scholar

8 Buchanan R, Heinrichs D: The Neurological Evaluation Scale (NES): a structured instrument for the assessment of neurological signs in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 1989; 27:335–350Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Shrout PE, Fleiss JL: Intraclass correlation: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979; 86:420–428Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Overall J, Gorman D: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, in ECDEU Assessment Manual, edited by Guy W. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 157–165Google Scholar

11 Andreasen N: The Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, IA, University of Iowa, 1984Google Scholar

12 Andreasen N: The Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, IA, University of Iowa, 1983Google Scholar

13 Hedeker D, Gibbons R: MixReg: a computer program for mixed-effects regression analysis with autocorrelated errors. Computer Methods Programs Biomed 1996; 49:229–252Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Buchanan R, Kirkpatrick B, Heinrichs D, et al: Clinical correlates of deficit syndrome of Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:290–293Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 King D, Wilson A, Cooper S, et al: The clinical correlates of neurological soft signs in chronic schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1991; 158:770–775Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Kolakowska T, Williams A, Jambor K, et al: Schizophrenia with good and poor outcome, III: neurological soft signs, cognitive impairment and their clinical significance. Br J Psychiatry 1985; 146:348–357Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Sanders R, Forman SD, Keshavan M, et al: Test-retest stability of the neurological examination in schizophrenia (abstract). Biol Psychiatry 1996; 39:548Crossref, Google Scholar