CNS Sjögren's Syndrome

Abstract

Sjögren's syndrome is a common medical condition that may produce psychiatric symptoms. Untreated deficits can become permanent, sometimes resulting in death. The hypothesized mechanism involves CNS vasculitis. Psychoactive medications treat psychiatric symptoms but leave the underlying medical process unaffected. Laboratory tests to diagnose Sjögren's syndrome and specific treatments for this condition are improving.

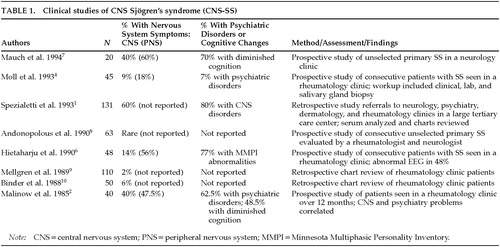

Sjögren's syndrome (SS) affects tear and saliva production but can also have central nervous system (CNS) manifestations. It can present as a psychiatric disorder,1 most commonly as an atypical mood disorder.1,2 However, psychosis2 and dementia,3 along with symptoms from somatization, dissociation, panic, and personality disorders,2 have also been described in the literature.4,5 Careful neuropsychiatric testing often reveals cognitive deficits.1,6,7Table 1 summarizes important findings reported in the literature.1,2,4,6–10

The following two cases highlight the clinical presentation of CNS-SS. The first patient presented with symptoms of dementia, personality change, and depression, and she also gave a history of periods of hypomania and psychosis, all in the context of a long medical history clinically suggestive of SS. Her treatment was different from that presented in earlier psychiatric case reports. In the second case, the patient presented with depression and prominent memory difficulties associated with fibromyalgia and chronic cough. Following the case reports, a review of the literature highlights recent discoveries that support earlier and more aggressive treatment of selected patients with SS.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1. Ms. S. is a 54-year-old woman who reported a history of sarcoid but no psychiatric history prior to age 53. Five months prior to outpatient psychiatric referral, she had fallen. After a negative medical evaluation, she was transferred to a psychiatric facility and placed on loxapine and diphenhydramine to treat ideas of reference and bizarre ideation. Historical material provided by the patient that could be construed as psychological but that could also reflect underlying brain disease included the patient's questioning her sexual orientation after many years of a stable and previously satisfying married life and a recent increase in exploring new lines of work.

Negative MRI and magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) ordered during her medical hospitalization made CNS sarcoid appear unlikely. At her initial psychiatric outpatient presentation she was not psychotic, but her recent history included increased capacity for work (three jobs), decreased sleep, rapid speech, and ideas of reference. Diphenhydramine was decreased and loxapine switched to haloperidol.

After 2 months of treatment with haloperidol, she began to exhibit symptoms consistent with a major depressive disorder. Consequently, she was begun on 10 mg of paroxetine. She subsequently briefly stopped haloperidol, but fearfulness and paranoid ideation recurred.

Six months later, Ms. S. was admitted to the neurology service for evaluation of new-onset hemiparesis. MRI and MRA indicated vascular lesions and vasculitis. An antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer was positive at 1:1,280. SS-A (Anti-Ro antibody) was positive and SS-B (Anti-La antibody) negative. Other markers for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) were negative. Chart review revealed multiple clinic visits for sinusitis and conjunctivitis related to dry mouth and eyes.

When she was started on prednisolone to treat purported pulmonary sarcoidoses, her paranoia remitted. At lower steroid doses, manic symptoms worsened and she began to exhibit bizarre behavior. She is currently being maintained on prednisolone at a dose of 7.5 mg qd. Her only psychiatric medication is divalproex 750 mg qd. The medical team is now questioning the diagnosis of pulmonary sarcoid. A lung biopsy would assist greatly in differentiating the caseating granulomatous process of sarcoid from the mononuclear inflammatory process often found in Sjögren's syndrome;11 however, because the patient has improved clinically, a biopsy has not been done.

Case 2. Ms. R. is a 47-year-old woman who presented to the psychiatry service for treatment of recurrent depression manifested by depressed mood, lethargy, diminished pain tolerance, and diminished libido. She also reported difficulty at work due to persistent fatigue and chronic cough. Six months earlier, she had responded to fluoxetine at a dose of 20 mg qd, but she stopped the medication because of side effects. Her depressive symptoms recurred and her work difficulty continued.

At her initial outpatient psychiatric evaluation, she complained of fatigue, hopelessness, feelings of discouragement, a diminished libido, poor concentration, and short-term memory disturbance. A review of her medical history revealed 4½ years of persistent nonproductive cough, frequent sinus problems, a long history of recurrent urinary tract infections with possible interstitial cystitis, two episodes of easy bruising, arthralgias without joint effusions, and myalgias. She also had an extensive medical workup for a lung infiltrate that was negative on biopsy, although erythema of the mucosa was noted on bronchoscopy. She was begun on isoniazid for treatment of a presumed case of tuberculosis based on her history of TB exposure and having a positive tuberculin purified protein derivative test (PPD). Unfortunately, this treatment regimen was not effective. Focused questioning revealed subjective complaints of dry eyes and mouth. A previous ANA titer ordered by her primary care physician was positive at 1:320, as was double-stranded-DNA (dsDNA); however, other SLE markers were negative. Clinical evidence of inflammatory processes required to diagnose SLE was also absent. Tests of the complement system (C3 and C4) were negative. A diagnosis of fibromyalgia was considered, but the patient lacked the requisite number of tender spots found on physical examination of the joints and extremities.

At the time of her presentation to the psychiatry service, an ANA titer was positive at 1:80 (speckled), but both SS-A (Anti-Ro antibody) and SS-B (Anti-La antibody) were negative. Venlafaxine was clinically effective but caused side effects that the patient could not tolerate. Buproprion was begun and partially relieved some depressive symptoms (frustration intolerance, hypersomnia, irritability, hopelessness, and guilt) but did not adequately address fatigue, myalgias, or cough.

The patient had an unsuccessful trial of antireflux therapy for her chronic cough. Prednisone at 5 mg qd was started. After being treated with bupropion 300 mg qd for 3 months, her fatigue, myalgias, and cough improved, and her depressive symptoms improved further. Shirmer's test (to quantify tear production) was positive, and a gingival biopsy revealed chronic sialadenitis without a mucosal lesion. She is currently being maintained on prednisone 10 mg qd. Her only psychiatric medication is bupropion 300 mg qd.

BACKGROUND

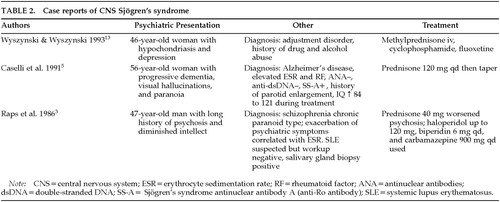

CNS Sjögren's syndrome (CNS-SS) is an underappreciated potential cause of psychiatric symptomatology (Table 1).12 Although substantial information on central SS exists in the rheumatology and neurology literature, a computer-assisted literature search using PsychINFO turned up only 11 articles, of which 4 were published in psychiatric journals. Table 1 and Table 23,5,13 summarize these papers.

SS is a chronic autoimmune exocrinopathy (causing progressive destruction of exocrine glands) with unclear pathogenesis.12 The most prominent symptoms are usually xerophthalmia and xerostomia. Salivary gland biopsy usually shows a destructive mononuclear cell infiltrate. Other exocrine glands may be affected: for example, mucous membranes of the upper airways and urogenital tract, the sweat glands, and even exocrine pancreatic function. Common complications can include recurrent otitis media, chronic sinusitis, accelerated dental caries, gingivitis, vaginitis, and laryngitis.1

SS is a relatively common disorder, affecting 2% to 3% of the general population.1,2,12,14 Women are nine times more likely to suffer from SS, and it is highly associated with rheumatoid arthritis. According to Bjerrum, as quoted by the Wyszynskis,13 “the average length of time between the initial complaints and eventual diagnosis of SS is 9 years.” Extraglandular pathology is protean but not the rule. Some investigators outside quaternary care institutions are documenting higher rates of nervous system disease than previously noted (see Table 1). Sjögren's syndrome in the peripheral nervous system (SS-PNS) can also complicate psychiatric presentations because PNS manifestations often involve “nonanatomic” distributions. Although SS generally does not afflict the central nervous system, most clinicians fail to consider CNS or PNS manifestations in their differential diagnosis.

PATHOLOGY

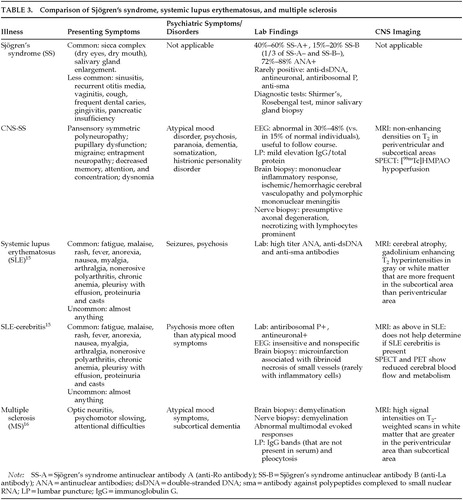

SS is similar to MS (multiple sclerosis) and SLE: all three follow unpredictable courses with waxing and waning autoimmune pathology (Table 3).15,16 However, in SS the antibodies affecting neurons are not as well described or understood as in MS and SLE. In SS, the mechanism differs from that of SLE in that it involves more than just transient cerebritis. In SLE, antineuronal, antiribosomal P, anti-dsDNA (against double-stranded DNA), and anti-sma (against polypeptides complexed to small nuclear RNA) antibodies are commonly found. The first two of these antibodies probably cause direct impairment of the neurons and are usually absent in SS. In CNS-SS, the most serious deficits appear to result from ischemic damage caused by vasculitis. Resulting neurologic deficits appear to be permanent and may fail to remit even with aggressive immunosuppressive therapy.14 The role of SS-A alone or in combination with other antibodies in CNS-SS brings up the question of unknown or poorly characterized antibodies playing roles in the pathogenesis of other poorly characterized or atypical CNS illness.

Interestingly, and in contrast to the work of Spezialetti et al.11 and Alexander,12 Moll et al.4 detected an antineuronal antibody in CNS-SS patients. Comorbid associations of CNS-SS with primary biliary colic (PBC), with Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and with celiac disease are additional curious findings.

DIAGNOSIS

Similar to psychiatric nosology, rheumatologic categorization involves many overlapping syndromes and postulated etiologic mechanisms. Thus, the distinction between secondary and primary SS is difficult and a source of debate in the rheumatologic literature. Secondary SS presents with the same symptoms as primary SS and may involve similar pathology (i.e., destruction of exocrine glands), but in secondary SS another medical condition (e.g., lymphoma or SLE), diagnosed and confirmed by its own set of diagnostic criteria and tests, explains the SS symptoms and changes. In this regard, other autoimmune illnesses are most problematic, occasionally having the same autoantibodies as those found in primary SS. As a general rule, primary SS has fewer extraglandular symptoms than secondary SS (e.g., secondary to SLE). SLE usually has many manifestations independent of exocrinopathy and cerebritis: fatigue, malaise, rash, fever, anorexia, nausea, arthralgias, myalgias (all occur at some point in 95% cases), nonerosive polyarthritis (60%), chronic anemia (70%), pleurisy with effusion (50% and 30%), proteinuria, and casts (50%)17 (Table 3).

A presentation of SLE-cerebritis would be difficult to distinguish from a presentation of SS-CNS in a patient with previously undiagnosed SS. Laboratory tests can help differentiate between the two diagnoses. Fortunately, initial treatment for both conditions involves the administration of steroids. In the presence of SS-A and symptoms consistent with SS-CNS, one could argue for aggressive treatment with steroids despite not being able to diagnose SLE. When the treatment for SLE becomes more specific, making the correct diagnosis will become increasingly important.

For now, differentiating whether the CNS symptoms are caused by primary SS, an undiagnosed cause of secondary SS (e.g., SLE), or an as yet uncharacterized rheumatologic illness is difficult. The tendency to change a diagnosis from SS to SLE with the advent of CNS problems is unsatisfying, since the markers for SLE are often absent. Some overlapping syndromes are felt to resemble SS more closely than SLE.14 Regardless of questions about categorization of SS with CNS manifestations, the association between SS with positive SS-A titers and a higher likelihood of poorer neurologic outcome, together with the high frequency of PNS abnormalities and high ratings of somatization and hypochondriasis, make patients with both clinical SS and psychiatric problems worthy of further investigation.

MEDICAL WORKUP

The diagnosis of SS involves clinical history with simple tests. Workup for SS includes a combination of ocular and oral diagnostic studies. Although the usual course of presentation includes complaints of dry mouth and eyes, occasionally these are absent.12 In contrast to diagnosing SS, diagnosis of CNS-SS, which is often done clinically, is much more involved, including ruling out other serious causes.

MRI scans of CNS-SS show increased intensity on T2-weighted and proton density–weighted images, predominantly in subcortical and periventricular white matter. These abnormalities are often fixed, do not resolve with treatment, and rarely enhance with gadolinium. SPECT scans show hypoperfusion and may be abnormal despite normal MRI scans. Cerebral angiography is useful to rule out other causes of CNS pathology. Occasionally, angitis or vasculitis will be apparent in SS. Unfortunately, a normal MRI and a normal angiography study do not rule out active CNS-SS.

A biopsy of meningeal or brain tissue allows the most definitive diagnosis. Alexander12 suggests this is necessary when causes such as malignancy and lymphoma need to be ruled out,2 when the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis is very reactive,3 or when the patient is rapidly deteriorating.

Although not particularly useful in diagnosis, EEGs and multimodal evoked response testing and blink reflex testing results are often abnormal, and when abnormal they can be used to follow patients.4 CSF analysis, like angiography, is most helpful in ruling out other causes of CNS diseases. CSF protein is usually normal, whereas the immunoglobulin G (IgG)/total protein ratio is often elevated. The IgG index is increased in about 50% of cases, and oligoclonal bands and a CSF pleocytosis occur in subsets of CNS-SS patients.

No particular laboratory test is always positive and confirmatory in CNS-SS. Antineuronal antibodies and antiribosomal P may be present, but in contrast to SLE they are not implicated as the mechanism of destruction.1 SS-A (anti-Ro) is detected in 40% to 60% of patients with SS by gel diffusion and in 10% to 15% of the normal population by a highly sensitive (but low specificity) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The Ro autoantigen is a small intracellular RNA-protein complex against which autoantibodies are synthesized by patients with SS. Its function is unclear, and Ro is probably a family of related peptides. SS-A by gel diffusion is associated with larger lesions on MRI, abnormal cerebral angiography, and more serious focal CNS findings, as well as global CNS problems. The study by Alexander12 even included data suggesting that the presence of SS-A increases the risk of death from a CNS-related event. SS-B is found in one-third of those with SS-A. Patients who are ANA negative are usually also SS-A negative. Rheumatoid factor and erythrocyte sedimentation rates are variably elevated and do not always correlate with SS disease activity.2 Positive titers remain positive over time and do not convert to false negatives.

PSYCHIATRIC ILLNESS

The incidence of mild to moderate psychiatric and cognitive impairment may be as high as 80% in patients with CNS-SS.1 Two studies using the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) found high rates of abnormalities on multiple scales. Hietaharju et al.6 found that 33 of 43 patients had at least one abnormal scale and for the group, the depression scale was more than 2 standard deviations above normal. Malinow et al.2 found that 33% of MMPI scales were abnormal, the highest three being the depression, hypochondriasis, and hysteria scales.

There is considerable variability among the figures cited by Spezialetti et al.,1 Alexander,12 Hietaharju et al.,6 and Moutsopoulos et al.18 The last-mentioned group cites a prevalence of psychiatric diagnosis suspiciously lower than the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study (ECA). At Johns Hopkins, Spezialetti and colleagues1 found that most patients suffered from both psychiatric and cognitive impairment. Interestingly, psychiatric problems were no more common in patients with nonfocal than focal neurologic deficits. Cognitive deficits were more common with nonfocal disease.

TREATMENT

CNS-SS is often misdiagnosed as MS or confused with SLE.1 Patients with MS are often seen by mental health professionals long before MS is diagnosed. The same may be true of CNS-SS. SS, like MS, requires additional somatic treatments. Given that the treatments for MS are growing more specific, effective, and distinct from the treatment of SS, early differentiation between disorders and from mental illness is increasingly important.

Although the treatments of SLE-cerebritis and CNS–SS are currently similar, mild CNS-SS may be more likely to be missed than SLE-cerebritis and therefore merits closer evaluation. Contributing to the need for early recognition, current evidence suggests that damage caused by CNS-SS in selected phases of the illness is permanent. If diagnosed early and treated, dementia and other psychiatric disorders caused by CNS-SS may be reversible.4,5,12

Steroids are often used to treat rheumatologic diseases. High doses of steroids are sometimes necessary to treat CNS-SS, leading to remarkably rapid relief of symptoms. Moll et al.4 prescribed a treatment regimen with prednisone 120 mg po daily. After only one week, the patient noted a marked diminishment in visual hallucinations and paranoid ideation, together with an increase in measured IQ from 84 to 121. Other authors have reported positive responses to immunosuppressants, such as asothioprine, methotrexate, and cyclosporine.12 These agents, although sometimes effective in similar illnesses, are not effective reliably enough to be prescribed routinely. Cyclophosphamide may be helpful if steroids prove inadequate. Plasmaphoresis may be used in secondary SS patients if hyperglobulinemia or cryoglobulinemia is found.12 Additionally, S-adenosyl-l-methionine is promising, along with steroids, to slow the course of the illness and to help the patient regain losses during the disease's early phases.19

CONCLUSION

When confronted with atypical or treatment-refractory psychiatric symptoms or disorders in patients with rheumatologic diseases, physicians should ask patients about dry mouth and eyes and, if they are present, order an ANA test (which may be only mildly positive with a speckled pattern) in order to rule out CNS-SS. In patients with known Sjögren's syndrome who present with psychiatric symptoms, ordering of SS-A and SS-B could facilitate recognition of the forms of SS that most rapidly cause permanent damage in the CNS via autoimmune vasculitis.

|

|

|

1 Spezialetti R, Bluestein HG, Alexander EL: Neuropsychiatric disease in Sjögren's syndrome: anti-ribosomal P and anti-neuronal antibodies. Am J Med 1993; 95:153–160Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Malinow KL, Molina R, Gordon B, et al: Neuropsychiatric dysfunction in primary Sjögren's syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1985; 103:344–349Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Raps A, Abramovich Y, Assael M: Relation between schizophrenic-like psychosis and Sjögren's syndrome (SS). Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 1986; 23:321–324Medline, Google Scholar

4 Moll JWB, Markusse HM, Pijnenburg JJM: Antineuronal antibodies in patients with neurologic complications of primary Sjögren's syndrome. Neurology 1993; 43:2574–2581Google Scholar

5 Caselli RJ, Scheithauer BW, Bowles CA, et al: The treatable dementia of Sjögren's syndrome. Ann Neurol 1991; 30:98–101Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Hietaharju JA, Yli-Kerttula U, Hakkinen V, et al: Nervous system manifestations in Sjögren's syndrome. Acta Neurol Scand 1990; 81:144–152Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Mauch E, Volk C, Kratzsch G, et al: Neurological and neuropsychiatric dysfunction in primary Sjögren's syndrome. Acta Neurol Scand 1994; 89:31–35Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Andonopoulos AP, Lagos G, Drosos AA, et al: The spectrum of neurological involvement in Sjögren's syndrome. Br J Rheumatol 1990; 29:21–21Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Mellgren SL, Conn DL, Stevens JC, et al: Peripheral neuropathy in primary Sjögren's syndrome. Neurology 1989; 39:390–394Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Binder A, Snaith ML, Isenberg D: Sjögren's syndrome: a study of its neurological complications. Br J Rheumatol 1988; 27:275–280Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Crystal RG: Sarcoidosis, in Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 11th edition, edited by Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, Petersdorf RG, et al. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1987, pp 1445–1450Google Scholar

12 Alexander EL: Neurologic disease in Sjögren's syndrome: mononuclear inflammatory vasculopathy affecting central/peripheral nervous system and muscle. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1993; 19:869–908Medline, Google Scholar

13 Wyszynski AA, Wyszynski B: Treatment of depression with fluoxetine in corticosteroid-dependent central nervous system Sjögren's syndrome. Psychosom 1993, 34:173–177Google Scholar

14 Alexander EL, Ranzenbach MR, Kumar AJ, et al: Anti-Ro (SS-A) autoantibodies in central nervous system disease associated with Sjögren's syndrome (CNS-SS): clinical, neuroimaging, and angiographic correlates. Neurology 1994; 44:899–908Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Ovsiew F: Neuropsychiatric aspects of the rheumatic diseases, in The American Psychiatric Press Textbook of Neuropsychiatry, 3rd edition, edited by Yudofsky SC, Hales RE. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997, pp 693–698Google Scholar

16 Cohen RA, Salloway S: Neuropsychiatric aspects of disorders of attention, in The American Psychiatric Press Textbook of Neuropsychiatry, 3rd edition, edited by Yudofsky SC, Hales RE. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997, pp 431–432Google Scholar

17 Hahn BH: Systemic lupus erythematosus, in Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 11th edition, edited by Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, Petersdorf RG, et al. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1987, pp 1418–1423Google Scholar

18 Moutsopoulos HM , Sarmas JH, Talal N: Is central nervous system involvement a systemic manifestation of primary Sjögren's syndrome? Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1993; 19:909–912Google Scholar

19 Ianniello A, Ostuni PA, Sfriso P, et al: S-adenosyl-l-methionine in Sjögren's syndrome and fibromyalgia. Current Therapeutic Research 1994; 55:699–706Crossref, Google Scholar