Distinctive Neurobehavioral Features Among Neurodegenerative Dementias

Abstract

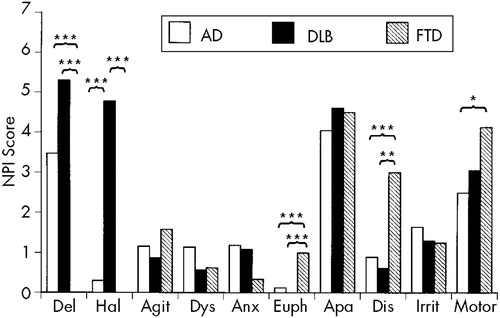

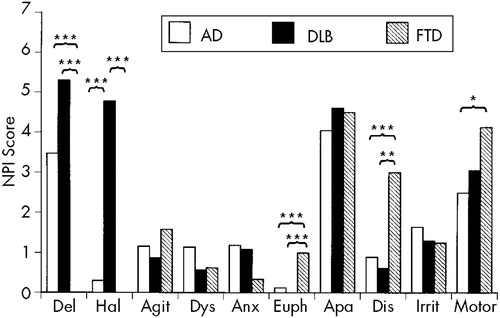

The distinctive neuropsychiatric features of Alzheimer's disease (AD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) were investigated by using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. The patients with FTD had significantly more euphoria, aberrant motor activity, and disinhibition and significantly fewer delusions compared with the patients with AD or DLB. The patients with DLB had significantly more hallucinations compared with the AD or FTD patients. The findings clearly demonstrate that AD, DLB, and FTD have distinctive neuropsychiatric features, which may correspond to different patterns of cerebral involvement characteristic of these three major degenerative dementias.

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia in most industrialized countries,1 and other types of neurodegenerative diseases are increasingly being recognized as important causes of dementia. Among them, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) are reportedly the second and third most common pathologies and thus are the ones that must be most carefully differentiated from AD in choosing the appropriate treatment for patients.2–9 DLB is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the presence of Lewy bodies in cortical and brainstem structures. In 1996, an international workshop recommended “Dementia with Lewy bodies” as a generic term and proposed criteria for clinical and pathological diagnosis.8 FTD is characterized by peculiar behavioral changes arising from frontotemporal involvement. In 1994, the Lund/Manchester groups proposed clinical and pathological criteria for FTD.9 According to these criteria, three types of histological change (Pick-type, frontal lobe degeneration type, and motor neuron disease type) underlie the atrophy, and there is preferential frontal and temporal lobar involvement in all three histological types.

Neuropsychiatric disturbances are common in these three most dementing illness. Elucidating their distinctive neuropsychiatric features can be effective not only for differentiating these diseases and choosing the appropriate neuropsychiatric management, but also for understanding the underlying mechanism of the behavioral symptoms. Neurobehavioral features of AD, DLB, and FTD have been described in the literature,10–26 although prospective comparative studies with quantitative evaluation are scarce.19,25,26 No study has been conducted that directly and quantitatively compares the neuropsychiatric disturbances of the three diseases. In the present study, to elucidate the distinctive neuropsychiatric features among AD, DLB, and FTD, we prospectively studied neuropsychiatric manifestations in patients with AD, DLB, or FTD by using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI),27,28 an established comprehensive tool for assessment of behavioral abnormalities in dementia.

METHODS

Subjects

All procedures of this study strictly followed the 1993 Clinical Study Guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Hyogo Institute for Aging Brain and Cognitive Disorders (HI-ABCD) and were approved by the Internal Review Board. After a complete description of all procedures of this study, written informed consent was obtained from patients or their relatives.

The subjects were 240 patients with sporadic AD, 23 patients with DLB, and 24 patients with FTD whose diagnosis was made on clinical grounds. They were selected on the basis of inclusion/exclusion criteria from a consecutive series of 671 patients who had been given a short-term admission for examination to the infirmary of the HI-ABCD, a research-oriented hospital for dementia, between August 1995 and March 1998. All of these patients were examined by both neurologists and psychiatrists and were given routine laboratory tests and standard neuropsychological examinations. In addition, electroencephalography, magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the brain, MR angiography of the neck and head, and cerebral perfusion/metabolism studies by positron emission tomography or single-photon emission computed tomography were done. All results were incorporated in the diagnosis. The inclusion criteria were the following: for AD, fulfilling thecriteria for probable AD of the National Institute ofNeurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association;29 for DLB, fulfilling the clinical criteria for probable DLB of the Consortium on DLB International Workshop;8 for FTD, fulfilling the Lund and Manchester criteria.9 The exclusion criteria were 1) complication of other neurological diseases or unstable medical illnesses such as diabetes mellitus, thyroid diseases, vitamin deficiencies, or malignant diseases; 2) history of previous psychotic illness or substance abuse before onset of dementia; 3) evidence of focal brain lesions on MR imagings; 4) absence of reliable informants; and 5) inability to obtain informed consent. We also excluded patients with AD or FTD who had apparent extrapyramidal signs. Although 367 patients with sporadic AD, 29 patients with DLB, and 41 patients with FTD fulfilled the inclusion criteria, in accordance with the exclusion criteria, 127, 6, and 17 of these patients, respectively, were excluded from this study.

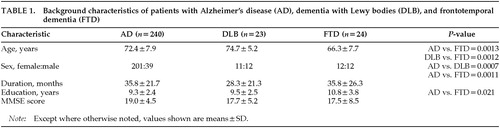

The demographic characteristics of the included patients are summarized in Table 1. The duration of illness was determined through an interview with the primary caregiver and was defined as the time in months between the first appearance of symptoms of sufficient severity to interfere with social or occupational functioning and the admission.30 The patients in the FTD group were significantly younger compared with the patients in the other two disease groups. The proportion of women was significantly higher in the AD group than in the other two groups. The AD group had less education than the FTD group. There was no significant difference in the duration of illness or the disease severity represented by the Mini-Mental State Examination31 among the three groups. There was no patient with DLB or FTD with a family history of dementia.

Assessment of Psychiatric Status

We assessed the patients' behavioral changes semiquantitatively during an interview with the caregiver, using a Japanese version27 of the NPI.28 Both the reliability and the validity of the Japanese version,27 like those of the original version,28 have been shown to be quite high. The Japanese version has been applied to Japanese patients with AD.32,33 A single board-certified neurologist (N.H.) was employed in the assessment. In the NPI, the following 10 behavioral and psychotic changes in dementia were rated on the basis of the patients' condition in the previous month before the interview: delusions, hallucinations, depression (dysphoria), anxiety, agitation and aggression, disinhibition, euphoria, irritability and lability, apathy, and aberrant motor activity. According to the criteria-based rating scheme, the severity of each manifestation was classified into grades (from 1 to 3; 0 if absent), and the frequency of each manifestation was also classified into grades (from 1 to 4; 0 if absent). The NPI score (severity×frequency) was calculated for each manifestation (range of possible scores, 0–12). The maximum total NPI score (for the 10 manifestations) is 120. Behavioral changes were also rated on a present/absent basis.

Statistical Analysis

The difference in each NPI manifestation score among three groups was tested by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc Scheffé test for comparisons between each pair of groups. To examine the frequency of each behavioral change, we used Fisher's exact probability test and post hoc Fisher's exact probability test with a Bonferroni correction for each pair comparison when an overall group difference was significant. The significance level was set at P<0.05. To identify the neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPI subset scores) most likely to discriminate the three groups, a stepwise discriminative function analysis was used with a significance level set at P<0.05.

RESULTS

The total NPI scores of the three groups (mean±SD) were 16.4±13.2 for AD, 22.2±15.9 for DLB, and 16.4±16. 6 for FTD, respectively, and the group difference was not significant (F=1.86, df=2,284, P=0.16). The mean scores of each NPI subset of the three groups are summarized in Figure 1. One-way ANOVA revealed significant group differences for the delusion (F=10.02, df=2,284, P<0.0001), hallucination (F=61.60, df=2,284, P<0.0001), euphoria (F=11.16, df=2,284, P<0.0001), disinhibition (F=7.43, df=2,284, P=0.0007), and aberrant motor activity (F=4.64, df=2,284, P=0.01) scores. The post hoc Scheffé test demonstrated that the FTD group's NPI scores were significantly lower for delusion and higher for euphoria and disinhibition than were the AD and DLB groups' and significantly higher for aberrant motor activity than was the AD group's. The DLB group had a significantly higher hallucination NPI score than did the AD and FTD groups.

The frequency of each neuropsychiatric symptom (on a present/absent basis), is summarized in Figure 2. Fisher's exact probability test revealed significant group differences for delusion (P<0.0001), hallucination (P<0.0001), dysphoria (P=0.0086), euphoria (P=0.048), and disinhibition (P=0.0023). The post hoc Fisher's exact probability test with Bonferroni correction demonstrated that delusions were less common and disinhibition was more common in the FTD group than in the AD and DLB groups. As for the types of delusions, both persecutory delusions (delusions that people are stealing things, delusions that the patient is being conspired against or harassed, and delusions of abandonment) and misidentification delusions (delusions that someone is in the house, delusions that the house is not the patient's own house, and delusions that television figures are actually present in the home) were less common in the FTD group (0.0% and 0.0%) than in the AD group (41.3% and 24.6%) and the DLB group (43.5% and 78.3%). Misidentification delusions were more common in the DLB group than in the AD group. Hallucinations were more common in the DLB group than in the AD and FTD groups. As for the types of hallucinations, visual hallucinations were more common in the DLB group (69.6%) than in the AD (3.3%) and FTD (0.0%) groups. Auditory hallucinations were also more common in the DLB (13.0%) group than in the AD (4.6%) and FTD (0.0%) groups, although the difference was not significant. No patients showed other modalities of hallucinations. Dysphoria was more common in the AD group than in the FTD group.

In a stepwise discriminant function analysis, four NPI scores retained significant F-values: hallucinations (F to enter=61.60; Wilks' lambda=0.70), euphoria (F to enter=11.63; Wilks' lambda=0.64), delusions (F to enter=7.53; Wilks' lambda =0.61), and aberrant motor behavior (F to enter=5.99; Wilks' lambda=0.59). The final equation using these four variables correctly assigned 77.5% of the AD, 52.2% of the DLB, and 58.3% of the FTD patients to the correct diagnostic groups.

DISCUSSION

Several methodological issues limit the interpretation of the results of this study. First, the diagnosis relied solely on a clinical basis without histopathologic confirmation. There is a controversy about the accuracy of the Consortium on DLB International Workshop criteria8 for differential diagnosis of DLB from AD. Mega et al.,34 evaluating the accuracy of the criteria based on the clinical records of patients with pathologically verified AD and DLB, reported an acceptably high specificity (79%–100%) and a relatively low sensitivity (40%–75%), whereas Papka et al.35 demonstrated a high sensitivity (88.9%) and low specificity of the criteria. The validity of the Lund/Manchester groups' clinical criteria for FTD9 has not yet been established. Therefore, there remains a possibility that patients with a different disease contaminated each diagnostic group. Nevertheless, although clinical studies are in fact influenced by the quality of clinical diagnosis, clinical studies with prospective clinical data collection can assess patients' neuropsychiatric manifestations more accurately than can autopsy studies with retrospective data review. Moreover, we supplemented the clinical diagnosis with neuroimaging studies. In addition, the presence of visual hallucinations is included in the criteria for probable DLB,8 and disinhibition and stereotyped and perseverative behaviors are included in the core diagnostic features in the criteria for FTD.9 These may affect the apparent prevalence of these symptoms, and the effect should be discounted when interpreting the results.

Second, a large number of patients were included in the AD group and only one-tenth as many in the other groups. Although this unbalance was caused by a different prevalence of these diseases, the small size of the DLB and FTD groups gives a modest statistical power.

Third, repeated comparisons in the present study raise the likelihood of an experimental Type I error. Corrections for repeated comparisons were not made because of the exploratory goals of this study and concerns about a Type II error. We finally avoided this possibility by applying a multivariate discriminate analysis.

Fourth, some of the demographic characteristics were significantly different among the three dementia groups. For example, we previously demonstrated that the patients' age and sex were related to delusions and hallucinations in AD.33 However, these different demographic characteristics were more likely to be caused by different disease properties than by a sampling bias. The duration of illness and the Mini-Mental State Examination score were at least comparable among the three disease groups.

Despite these limitations, we believe that our findings are quite reliable because they are based on 1) a consecutive patient series whose diagnosis was carefully made with widely accepted clinical criteria, and 2) an established comprehensive tool for the assessment of behavioral abnormalities.

Our results demonstrated that disinhibition, euphoria, and aberrant motor behavior were significantly more common and severe, and that delusions, hallucinations, and depression were significantly less common, in the FTD patients. Our findings were in agreement with previous comparative studies of AD and FTD,20–26 although there has never been a direct comparison between FTD and DLB. Lewy et al.,25 examining patients with AD and other patients with FTD with the NPI, noted that disinhibition, aberrant motor behavior, euphoria, and apathy scores were significantly higher in the patients with FTD. They also noted that the depression score was lower in patients with FTD. Barber et al.,24 in a study in which neuropsychiatric changes of patients with autopsy-proven FTD and AD were retrospectively examined by questioning their close relatives, found that patients with FTD were more likely to exhibit early personality changes such as disinhibition and socially inappropriate behaviors and less likely to exhibit delusions and hallucinations than were patients with AD. Gustafson20 also noted that hallucinations were less frequent in the FTD patients than in the AD patients.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are reportedly very common in patients with DLB and are considered to be a central feature of this disease.8,10–19 Our study quantitatively confirmed previous observations that most patients with DLB had visual hallucinations. Delusions and hallucinations in other sensory modalities, which are regarded as supportive features of DLB,8 were reported to be significantly more common in patients with DLB than in patients with AD.10,12,13,17 However, in the present study, the severity and frequency of delusions and auditory hallucinations in patients with DLB did not significantly differ from those with AD. More interestingly, a more distinctive difference between delusions in AD and delusions in DLB was the type of delusion: misidentification delusions, not persecutory delusions, were significantly more common in the patients with DLB than in those with AD. Ballard et al.17 also reported that delusional misidentification was significantly more common in DLB than in AD.

These different patterns of neuropsychiatric features among diseases can be attributed to the different patterns of cerebral involvement. In FTD, there is a predominant involvement of the anterior cerebrum,9,36,37 whereas posterior involvement predominates both in AD38,39 and DLB.40–42 Moreover, decreased occipital metabolism are disproportionately more severe in DLB than in AD.40–42 Therefore, the features of behavioral abnormality in FTD (i.e., disinhibition and euphoria) are related to frontal involvement.43 Although depression is also considered to be associated with frontal dysfunction,32,43 this symptom was not common in FTD. This pattern can be explained by the way in which depression is defined by the NPI. The NPI depression items are designed to focus on mood changes28 rather than on anhedonia or vegetative symptoms, although anhedonia with vegetative symptoms is generally, for example in the DSM-IV, weighted equivalently to mood changes for the diagnosis of major depression.1 Feelings of sadness and melancholia will be concealed by apathy when frontal dysfunction is severe, as it is in FTD. On the other hand, delusions and hallucinations, which are more frequent in AD and DLB, involve the posterior cerebral region. Among the delusions and hallucinations, visual hallucinations and misidentification delusions were more common in DLB than in AD. Therefore, these manifestations may be related to occipital involvement, which is more severe in DLB than in AD. This hypothesis is supported by findings that unilateral or bilateral medial occipital ischemic lesions often produce agitated delirium,44,45 which is mainly characterized by hallucinations and delusions.46 Our previous study of delusions in AD,47 which found a correlation between decreased relative regional glucose metabolism in medial occipital cortices and delusions, may also support this hypothesis.

In summary, AD, DLB, and FTD have different patterns of neuropsychiatric symptoms. The distinctive neuropsychiatric features may correspond to different patterns of cerebral involvement characteristic to these three major degenerative dementias. However, as there is considerable overlap, the utility of this finding in differential diagnosis on a case-by-case basis may be limited.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Tatsuo Shimomura, M.D., Hikari Yamashita, M.A. (Division of Clinical Neurosciences), Hajime Kitagaki, M.D., and Kazunari Ishii, M.D. (Division of Neuroimaging Research) for their help with parts of the study.

FIGURE 1. Mean composite scores (frequency×severity) for behavioral symptoms in patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) measured by the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI)*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

FIGURE 2. Frequency of each behavioral symptom in patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) measured by the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI)*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

|

1 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

2 Perry RH, Irving D, Blessed G, et al: Senile dementia of Lewy body type: a clinical and neuropathologically distinct form of Lewy body dementia in the elderly. J Neurol Sci 1990; 95:119–139Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Hansen L, Salmon D, Galasko D, et al: The Lewy body variant of Alzheimer's disease: a clinical and pathological entity. Neurology 1990; 40:1–8Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Dickson DW, Ruan D, Crystal H, et al: Hippocampal degeneration differentiates diffuse Lewy body disease (DLBD) from Alzheimer's disease: light and electron microscopic immunocytochemistry of CA2–3 neurites specific to DLBD. Neurology 1991;41:1402–1409Google Scholar

5 Gustafson L: Clinical picture of frontal lobe degeneration of non-Alzheimer type. Dementia 1993; 4:143–148Medline, Google Scholar

6 Pasquier F, Petit H: Frontotemporal dementia: its rediscovery. Eur Neurol 1997; 38:1–6Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Kosaka K: Diffuse Lewy body disease in Japan. J Neurol 1990; 237:197–204Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, et al: Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the Consortium on DLB International Workshop. Neurology 1996; 47:1113–1124Google Scholar

9 Brun A, Englund B, Gustafson L, et al: Clinical and neuropathological criteria for frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994; 57:416–418Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 McKeith IG, Perry RH, Fairbairn AF, et al: Operational criteria for senile dementia of Lewy body type (SDLT). Psychol Med 1992; 22:911–922Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Ballard CG, Mohan RNC, Patel A, et al: Idiopathic clouding of consciousness: do the patients have cortical Lewy body disease? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1993; 8:571–576Google Scholar

12 McKeith IG, Fairbairn AF, Bothwell RA, et al: An evaluation of the predictive validity and inter-rater reliability of clinical diagnostic criteria for senile dementia of Lewy body type. Neurology 1994; 44:872–877Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Weiner MF, Risser RC, Cullum CM, et al: Alzheimer's disease and its Lewy body variant: a clinical analysis of postmortem verified cases. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1269–1273Google Scholar

14 Galasko D, Katzman R, Salmon DP, et al: Clinical and neuropathological findings in Lewy body dementias. Brain Cogn 1996; 31:166–175Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Klatka LA, Louis ED, Schiffer RB: Psychiatric features in diffuse Lewy body disease: a clinicopathologic study using Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease comparison groups. Neurology 1996; 47:1148–1152Google Scholar

16 Galasko D, Salmon DP, Thal LJ: The nosological status of Lewy body dementia, in Dementia with Lewy Bodies, edited by Perry RH, McKeith IG, Perry EK. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp 21–32Google Scholar

17 Ballard C, Lowery K, Harrison R, et al: Noncognitive symptoms in Lewy body dementia, in Dementia with Lewy Bodies, edited by Perry RH, McKeith IG, Perry EK. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp 67–84Google Scholar

18 Ala TA, Yang KH, Sung JH, et al: Hallucinations and signs of parkinsonism help distinguish patients with dementia and cortical Lewy bodies from patients with Alzheimer's disease at presentation: a clinicopathological study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997; 62:16–21Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Hirono N, Mori E, Imamura T, et al: Neuropsychiatric features in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease. No to Shinkei 1998; 50:45–49Medline, Google Scholar

20 Gustafson L: Frontal lobe degeneration of non-Alzheimer type, II: clinical picture and differential diagnosis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 1987; 6:209–223Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Nearly D, Snowden JS, Northen B, et al: Dementia of frontal lobe type. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988; 51:353–361Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Miller BL, Cummings JL, Villanueva-Meyer J, et al: Frontal lobe degeneration: clinical, neuropsychological, and SPECT characteristics. Neurology 1991; 41:1374–1382Google Scholar

23 Mendez MF, Selwood A, Mastri AR, et al: Pick's disease versus Alzheimer's disease: a comparison of clinical characteristics. Neurology 1993; 43:289–292Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Barber R, Snowden JS, Craufurd D: Frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease: retrospective differentiation using information from informants. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1995; 59:61–70Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Lewy ML, Miller BL, Cummings JL, et al: Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal dementias. Behavioral distinction. Arch Neurol 1996; 53:687–690Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Swartz JR, Miller BL, Lesser IM, et al: Behavioral phenomenology in Alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal dementia, and late-life depression: a retrospective analysis. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1997; 10:67–74Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Hirono N, Mori E, Ikejiri Y, et al: Japanese version of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory: a scoring system for neuropsychiatric disturbances in dementia patients. No to Shinkei 1997; 49:266–271Medline, Google Scholar

28 Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al: The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994; 44:2308–2314Google Scholar

29 McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al: Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology 1984; 34:939–944Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Sano M, Devanand DP, Richards M, et al: A standardized technique for establishing onset and duration of symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. Arch Neurol 1995; 52:961–966Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: ”Mini-Mental State“: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 Hirono N, Mori E, Ishii K, et al: Frontal lobe hypometabolism and depression in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1998; 50:380–383Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 Hirono N, Mori E, Yasuda M, et al: Factors associated with psychotic symptoms in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998; 64:648–652Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 Mega MS, Masterman DL, Benson DF, et al: Dementia with Lewy bodies: reliability and validity of clinical and pathological criteria. Neurology 1996; 47:1403–1409Google Scholar

35 Papka M, Rubio A, Schiffer RB, et al: Lewy body disease: can we diagnose it? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 10:405–412Google Scholar

36 Kamo H, McGeer PL, Harrop R, et al: Positron emission tomography and histopathology in Pick's disease. Neurology 1987; 37:439–445Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 Ishii K, Sakamoto S, Sasaki M, et al: Cerebral glucose metabolism in patients with frontotemporal dementia. J Nucl Med 1998; 39:1875–1878Google Scholar

38 Frackowiak RS, Pozzilli C, Legg NJ, et al: Regional cerebral oxygen supply and utilization in dementia: a clinical and physiological study with oxygen-15 and positron tomography. Brain 1981; 104:753–778Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39 Friedland RP, Brun A, Buldinger TF: Pathological and positron emission tomographic correlation in Alzheimer's disease (letter). Lancet 1985; i:228Google Scholar

40 Albin RL, Minoshima S, D'Amato CJ, et al: Fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography in diffuse Lewy body disease. Neurology 1996; 47:462–466Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41 Imamura T, Ishii K, Sasaki M, et al: Regional cerebral glucose metabolism in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease: a comparative study using positron emission tomography. Neurosci Lett 1997; 235:49–52Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42 Ishii K, Imamura T, Sasaki M, et al: Regional cerebral glucose metabolism in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1998; 51:125–130Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43 Cummings JL: Frontal-subcortical circuits and human behavior. Arch Neurol 1993; 50:873–880Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44 Medina JL, Rubino FA, Ross E: Agitated delirium caused by infarctions of the hippocampal formation and fusiform and lingual gyri: a case report. Neurology 1974; 24:1181–1183Google Scholar

45 Devinsky O, Bear D, Volpe BT: Confusional states following posterior cerebral artery infarction. Arch Neurol 1988; 45:160–163Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46 Lipowski ZJ: Delirium (acute confusional states). JAMA 1987; 258:1789–1792Google Scholar

47 Hirono N, Mori E, Ishii K, et al: Alteration of regional cerebral glucose utilization with delusions in Alzheimer's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 10:433–439Link, Google Scholar