Pedophilia and Temporal Lobe Disturbances

Abstract

Paraphilias may occur with brain disease, but the nature of this relationship is unclear. The authors report 2 patients with late-life homosexual pedophilia. The first met criteria for frontotemporal dementia; the second had bilateral hippocampal sclerosis. Both were professional men with recent increases in sexual behavior. In both, 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography revealed prominent right temporal lobe hypometabolism. These cases and the literature suggest that bilateral anterior temporal disease affecting right more than left temporal lobe can increase sexual interest. A predisposition to pedophilia may be unmasked by hypersexuality from brain disease. These observations have potential implications for all neurologically based paraphilias.

The older medical literature contains references to “dirty old men” who are predisposed to molest children.1 These writings often describe these older men as having dementia or diseases such as neurosyphilis or stroke. The widely held belief that most pedophiles have neurological disease, however, is not supported by the more recent literature. In the overwhelming majority of cases, pedophilia begins among adolescent, often “psychosexually retarded” males.2 Nevertheless, there are case reports of pedophilia beginning with a brain disease in later life.1 Brain lesions can cause hypersexuality or sexual disinhibition, but the association between pedophilia and brain disease is controversial. Specific brain lesions could alter sexual orientation toward children or, alternatively, facilitate or release a pedophilic orientation in predisposed individuals. We report two older men who presented with pedophilia and a brain disease and review the neuropsychiatry of this condition.

CASE REPORTS

Patient 1. The patient is a 60-year-old left-handed male hospitalized after stalking, accosting, and attempting to molest children. For 18 months he followed children home from school in his car and tried to touch them. At one point, he put his arm around a 10-year-old boy and then struck him when he tried to pull away. He stood at the foot of a pool and leered at the boys, and he exposed himself in front of his neighbor's children. His family was concerned that he would molest the children and would be arrested. The family felt that he had a pronounced increase in sexual activity and in conjugal demands.

The patient had had a decline in memory and personality over the preceding 4 years. His personal appearance had deteriorated; he wore the same clothes every day and stopped showering. He intruded into others' conversations and walked into offices that he had no business entering. He constantly pilfered items. In restaurants, he would fill his pockets with sugar packets and napkins, and at one point he had a collection of 28 umbrellas that he had taken from others. His eating behavior had changed as well, and he was eating indiscriminately, taking others' food and even going through and eating from the garbage. He also compulsively took photographs of the sunset every night. Over the preceding weeks he had become verbally and physically aggressive. Recently, his driver's license had been suspended because of a hit-and-run accident.

The patient was a former college professor who was being divorced by his wife because of his behavior. In extended family interviews and sessions, family members said that a minister might have molested him at age 18 and that he, in turn, had molested his son when the latter was a small child about 35 years before. The son would not discuss or elaborate on this further. The patient's family history was positive for an unspecified dementia in his mother.

On examination, the patient denied a sexual interest in children and believed that he was hospitalized because “talking to strangers was not the right thing to do.” He did not endorse hallucinations, delusions, or paranoia. He was irritable and showed utilization behavior and hyperorality during the interview. His basic attention span was normal, and he was oriented to place and time. He was mildly echolalic, with decreased word generation and verbal stereotypies such as “oh my” repeated over and over again. Comprehension for three-step commands and repetition of spoken language were intact, but confrontational naming was decreased. Verbal memory and nonverbal memory were impaired. Simple constructions were normal. His interpretations of proverbs were concrete, and he had marked perseverations but had no difficulty with Luria hand sequences. The neurological examination disclosed normal cranial nerve, coordination, motor, sensory, and reflex results.

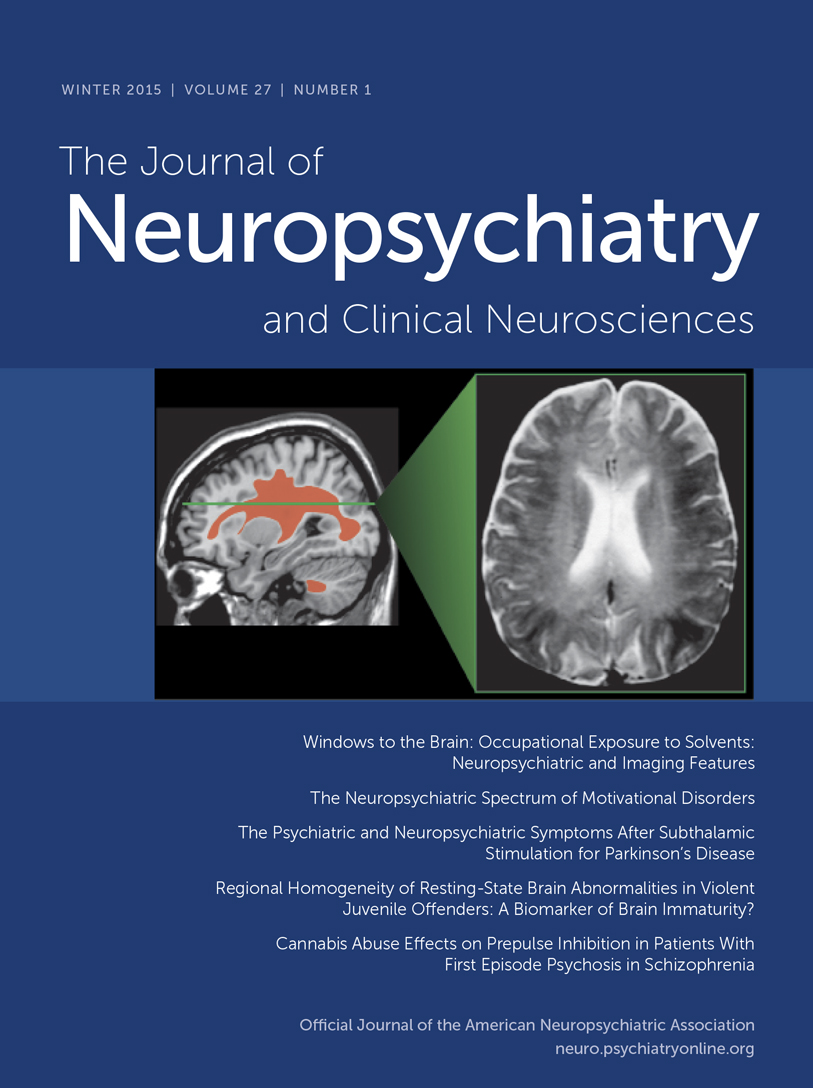

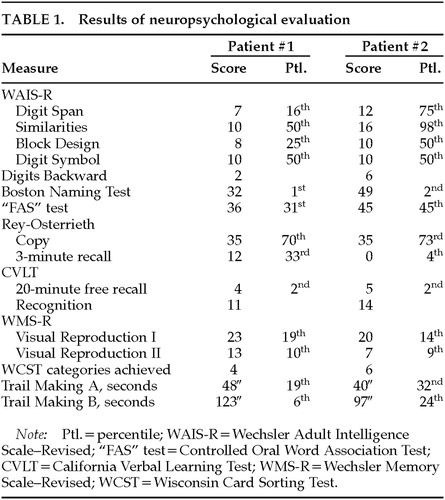

Neuropsychological testing (Table 1) showed significant memory impairment, less dramatic declines in executive functions, and relatively poor Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised subtest scores, given his background as a college professor. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain did not disclose abnormalities. 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) imaging, however, showed a prominent area of focal hypometabolism in the right inferior temporal region, with subtler hypometabolism in the left temporal lobe (Figure 1).

The patient met Lund and Manchester criteria for frontotemporal dementia3 (FTD), with a personality change characterized as a progressive decline in social and personal awareness and behavioral changes reflecting decreased judgment and compulsive behavior. The patient was started on paroxetine 20 mg qhs, valproate 500/750 mg, and conjugated estrogens 0.625 mg qd. With this medical regimen and increased supervision, the patient had significant behavioral improvement, including a decrease of his sexual interest in children.

Patient 2. A 67-year-old right-handed artist presented for neuropsychiatric evaluation after spending 18 months in jail for child molestation. He gave an unsolicited “massage” to a 14-year-old boy. He denied sexual intent and claimed to have been demonstrating the technique of pressure point massage. The patient had shown a heightened sexual interest during the prior 2 or more years and constantly sought female companionship. He incessantly spoke of multiple girlfriends, who tended to be much younger than he was.

The patient also complained of severe memory difficulty present during the same period of time. He forgot what was told to him, where he left things, and how to get places. He had trouble remembering appointments and forgot to pay his bills. In addition, the patient was depressed. He had suicidal ideation and contemplated using a gas stove or inhalation from his car exhaust to kill himself.

His past history was significant for angina pectoris, responsive to sublingual nitroglycerin, and probable cardiac arrhythmias. He had an extensive history of alcohol and drug use, with crack cocaine binges lasting days. As a young man, he was an amateur boxer but never sustained a loss of consciousness. Detailed family interviews disclosed that he was estranged from his grown son. When contacted, the son claimed to have been molested by his father as a child 30 years previously and refused to have anything to do with him now. His family history was otherwise significant for three uncles and one aunt who committed suicide.

On examination, the patient was talkative and engaging, with good eye contact and a ready smile. The patient appeared much less depressed than his stated mood. He attempted to flirt with female examiners and at one point exposed himself to a female physician. The patient's thought processes were logical and clear, and he denied any hallucinations or delusions. He was alert and attentive but scored 24/30 on the Mini-Mental State Examination,4 missing the three memory items and three orientation items. Language was fluent, with good comprehension, repetition, and naming. He generated a word list of 20 animals in a minute. Constructional tasks and proverb interpretation were normal. The neurologic examination revealed intact cranial nerves, coordination and gait, and motor and sensory systems. His reflexes were 2+ and symmetrical, with bilateral Babinski responses but negative snout, grasp, or glabellar reflexes.

The patient had yearly neuropsychological testing over the next 3 years. His scores on these tests did not significantly change over this time period. He remained with markedly impaired verbal and nonverbal memory and decreased confrontational naming (Table 1). He scored 24 on the Beck Depression Inventory,5 which is in the moderate range of depressive symptoms.

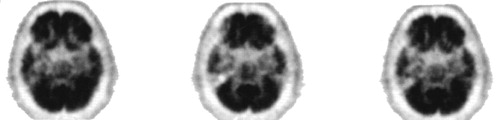

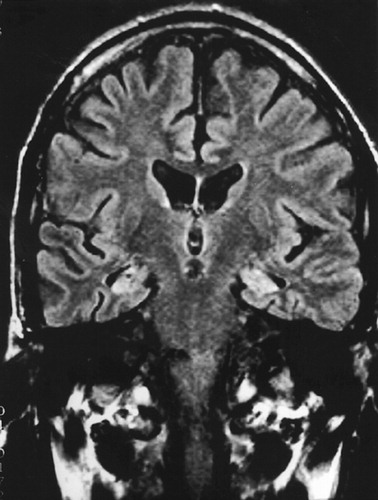

Laboratory tests revealed several abnormalities. An electrocardiogram showed occasional premature ectopic complexes. MRI of the head disclosed increased signal intensity and volume loss in the mesial temporal lobes along the hippocampal formations, consistent with bilateral hippocampal sclerosis (Figure 2). The patient had serial PET scans over the 3-year period, which showed a stable area of decreased metabolism in the right temporal lobe (Figure 3).

The patient's serial clinical, neuropsychological, and neuroimaging examinations did not indicate a progressive dementing process. Unfortunately, during this period the patient was charged with molesting a 5-year-old boy. His behavior subsequently improved with sertraline therapy and a carefully supervised environment.

DISCUSSION

These two patients presented with pedophilia and demonstrated right temporal lobe hypometabolism on FDG-PET. The etiologies of their brain disorders were different. Although one had frontotemporal dementia and the other had bilateral hippocampal sclerosis (HS), their similar PET findings suggested a role for right temporal lobe dysfunction in their pedophilia. Extensive family interviews disclosed that an orientation to pedophilia was present at a younger age. An increase in sexuality from temporal lobe disease probably unmasked latent pedophilia in these two patients.

Concern over pedophilia has increased in recent years.2 Although pedophiles may be otherwise “normal,”6 they are often immature men with a great many sexual conflicts and without the assertiveness necessary for sexual relations with mature women.7–9 Pedophiles often report being sexually abused as children.10 With the conflicts and stigma associated with pedophilia, a predisposition to this behavior may lie dormant until a pedophilic episode is released by some factor, such as brain disease, in later life.11

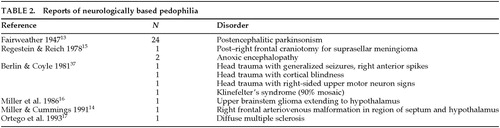

Investigators have reported pedophilia in patients with neurological disorders. In an early report, nearly one-third (31) of 111 individuals arrested for pedophilia had a poorly specified “organic mental syndrome” or mental retardation.12 Among 34 other patients reported in the literature, most were postencephalitic parkinsonism patients from one study, 24 of whom had heterosexual pedophilia.13 The remaining reported patients had a range of disorders (Table 2). These include a 64-year-old man, arrested for sex with a juvenile, who had a right frontal arteriovenous malformation extending into the septal region;14 a 49-year-old man who molested children after undergoing a right frontal craniotomy for removal of a suprasellar meningioma;15 and a progressively hypersexual man who propositioned children and had a glioma involving the hypothalamus and upper brainstem.16 Incestuous pedophilia has followed global cerebral hypoxia in patients who had myocardial infarctions and underwent cardioversion.15 A further report describes a patient with multiple paraphilias and widespread demyelinating lesions from multiple sclerosis.17

Increased or altered sexual behavior may result from specific brain lesions. The Klüver-Bucy syndrome includes hypersexuality.18 Originally described in monkeys following bilateral anterior temporal lobectomies, this syndrome involves increased autoerotic and sexual activity, sometimes with inappropriate object choice; hyperorality and hyperphagia; placidity and loss of fear; hypermetamorphosis (a tendency to attend to any visual stimulus); and visual agnosia. Patients with FTD are particularly prone to this syndrome,3,19,20 and Patient 1 had elements of the Klüver-Bucy syndrome. Moreover, in humans this syndrome may produce a change in sexual preference as well as a true hypersexuality.18 Other clinical reports implicate the right temporal lobe more than the left one in producing altered sexual behavior. Kalliomaki et al.21 found that 8.3% of their right-hemisphere stroke patients but only 4.4 percent of their left-hemisphere stroke patients had increased libido, and some authors note a markedly increased sexual desire after strokes involving the right anterior temporal lobe.16,22 In addition, among 12 women with sexual ictal manifestations,23 epileptiform activity emanated from the right temporal lobes in 8, including 1 patient with a right temporal astrocytoma. Hypersexuality also can result from damage to the septal region16,24 and the hypothalamic region.16,25 The Kleine-Levin syndrome with periodic hypersomnolence can include hypersexuality and probably results from hypothalamic dysfunction. Finally, the frontal lobes are involved in regulating the expression of sexual behavior. Orbitomedial frontal lesions, however, usually result in disinhibited sexual commentary rather than in a true increase in libido.

Patient 1 had frontotemporal dementia. This disorder may be asymmetric and involve the right hemisphere more than the left or the temporal lobes more than the frontal lobes. Bizarre behavior, compulsive-like acts, and changes in personality predominate with right-hemisphere FTD.19 Patient 1, who met Lund and Manchester criteria for FTD,3 appeared to have the right temporal lobe variant of this disorder.20 Temporal variants account for about 20% of patients with FTD and feature predominant anterior temporal and basal-frontal hypometabolism. It is the patients with right-sided temporal variants of FTD who are particularly sexually aggressive, make sexual advances, and have altered sexual orientation.20 Like Patient 1, the right temporal variant FTD patients display social ineptness, irritability and agitation, eccentric or bizarre thinking, poor personal hygiene, eccentric or intense ideas, and perceptual changes. In contrast, patients with the left temporal variant of FTD are primarily aphasic but socially appropriate.

Patient 2 had hippocampal sclerosis rather than a progressive dementia. HS is a potential cause of memory and personality changes, especially in dementia patients 80 years or older, but HS can occur in patients as young as 59 years old.26–30 Clinicians may find it difficult to distinguish patients with HS from those with dementias such as Alzheimer's disease.27,29,31 The occurrence of progressive deterioration of cognitive function in HS patients may relate to other pathologic changes, such as neocortical synapse loss, or to concomitant neuritic plaques.26 Cardiovascular disease, episodes of heart failure, or a history of myocardial infarction are present in about 88% these patients, implying an anoxic or ischemic etiology for HS.26,28,32 The hippocampi are especially vulnerable to even subclinical hypoxic or ischemic injuries. Furthermore, similar to Patient 2, most patients with HS have depressive symptoms but lack a history of seizures.26

Prior animal work has defined the critical regions for sexual behavior and orientation. The expression of sexual behavior ultimately depends on the hypothalamus and the septal region.33 In animals, stimulation of the preoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus results in copulation behavior, whereas ablation results in loss of sexual activity.34 The activity of some preoptic neurons is maximal after visual contact with a potential sexual partner.35 Moreover, sexual feelings are readily elicited by stimulation of the septal nuclei rostral to the anterior commissure.33 Portions of the frontal and temporal lobes serve a regulating role on sexual behavior from the hypothalamus and septal region. The right temporal lobe participates in providing emotional coloring and in interpreting emotion expression, elements involved in modulating normal sexual arousal. The absence of severe behavioral disturbances in right temporal lobectomized patients, however, indicates that sexual behavioral changes require bitemporal involvement. Both Patient 1 and Patient 2 had evidence of bitemporal involvement, with greater disturbances of the right temporal lobes. Alternatively, the frontal lobes may have contributed to sexual disinhibition. This is less likely, however, because both patients had a true increase in sexual interests and behavior as well as a probable predisposition to pedophilia.

We conclude that bilateral temporal lobe disturbances involving the right more than the left result in hypersexuality. This sexuality change is probably part of the spectrum of the Klüver-Bucy syndrome. Hypersexuality may unmask a previously hidden orientation toward molesting children. Hypersexuality could also unmask predispositions to other paraphilias. Moreover, the literature to date does not reveal the presence of a specific “pedophilia lesion” in the brain. Undoubtedly, further work is needed to understand the neuropsychiatry of this disorder, as well as its potential responsiveness to anti-androgen, estrogen, selective serotonin receptor inhibition, and other treatments.36

FIGURE 1. Positron emission tomography scan of Patient 1The patient was scanned in the fasting state 40 minutes after intravenous administration of 10 mCi of [18F]2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose, using the Siemens ECAT-953 tomographic scanner. The head was positioned so that the planes of the images were parallel to the canthomeatal line. There is an area of decreased metabolism in the right temporal lobe. There is more subtle decreased metabolism in the left temporal region.

FIGURE 2. Magnetic resonance image of Patient 2Fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI scan with coronal cuts shows increased signal intensity along the hippocampal formation bilaterally extending into the nuclei. This finding is bilateral and relatively symmetrical. The findings are consistent with hippocampal sclerosis.

FIGURE 3. Positron emission tomography scan of Patient 2The patient was scanned in the fasting state 40 minutes after intravenous administration of 12.15 mCi of [18F]2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose. The head was positioned so that the planes of the images were parallel to the canthomeatal line. There is prominent hypometabolism in the right temporal lobe. There is subtle left temporal lobe hypometabolism. The remaining cortical and subcortical gray matter structures are unremarkable. This scan was the second of three yearly PET scans obtained on this patient.

|

|

1 Kurland M: Pedophilia erotica. J Nerv Ment Dis 1960; 131:394–403Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 McConaghy N: Paedophilia: a review of the evidence. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1998; 32:252–265 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 The Lund and Manchester Groups: Clinical and neuropathological criteria for frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994; 57:416–418Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Beck AT: Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio, TX, The Psychological Corporation, 1987Google Scholar

6 Glaser B: Psychiatry and paedophilia: a major public health issue. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 1998; 32:162–167Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Bridges MR, Wilson JS, Gacono CB: A Rorschach investigation of defensiveness, self-perception, interpersonal relations, and affective states in incarcerated pedophiles. J Pers Assess 1998; 70:365–385Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Haywood TW, Kravitz HM, Wasyliw OE, et al: Cycle of abuse and psychopathology in cleric and noncleric molesters of children and adolescents. Child Abuse and Neglect 1996; 20:1233–1243Google Scholar

9 Smiljanich K, Briere J: Self-reported sexual interest in children: sex differences and psychosocial correlates in a university sample. Violence and Victims 1996; 11:39–50Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Freund K, Kuban M: The basis of the abused abuser theory of pedophilia: a further elaboration on an earlier study. Arch Sex Behav 1994; 23:553–563Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Cormier BM, Fugere R, Thompson-Cooper I: Pedophilic episodes in middle age and senescence: an intergenerational encounter. Can J Psychiatry 1995; 40:125–129Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Henn FA, Herjanic M, Vanderpearl RH: Forensic psychiatry: profiles of two types of sexual offenders. Am J Psychiatry 1976; 133:694–696Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Fairweather DS: Psychiatric aspects of the post-encephalitic syndrome. Journal of Mental Science 1947; 391:200–254Google Scholar

14 Miller BL, Cummings JL: How brain injury can change sexual behavior. Medical Aspects of Human Sexuality 1991; 1:54–62Google Scholar

15 Regestein QR, Reich P: Pedophilia occurring after onset of cognitive impairment. J Nerv Ment Dis 1978; 166:794–798Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Miller BL, Cummings JL, McIntyre H, et al: Hypersexuality or altered sexual preference following brain injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1986; 49:867–873Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Ortego N, Miller BL, Itabashi H, et al: Altered sexual behavior with multiple sclerosis: a case report. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1993; 6:260–264Google Scholar

18 Lilly R, Cummings JL, Benson DF, et al: The human Klüver-Bucy syndrome. Neurology 1983; 33:1141–1145Google Scholar

19 Miller BL, Chang L, Mena I, et al: Progressive right frontotemporal degeneration: clinical, neuropsychological and SPECT characteristics. Dementia 1993; 3:204–213Google Scholar

20 Edwards-Lee T, Miller BL, Benson DF, et al: The temporal variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 1997; 120:1027–1040Google Scholar

21 Kalliomaki JL, Markkanen TK, Mustonen VA: Sexual behavior after cerebral vascular accident. Fertility and Sterility 1961; 12:156–159Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Monga TN, Monga M, Raina MS, et al: Hypersexuality in stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1986; 67:415–417Medline, Google Scholar

23 Remillard GM, Andermann F, Testa GF, et al: Sexual ictal manifestations predominate in women with temporal lobe epilepsy: a finding suggesting sexual dimorphism in the human brain. Neurology 1983; 33:323–330Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Gorman DG, Cummings JL: Hypersexuality following septal injury. Arch Neurol 1992; 49:308–310Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Cummings JL, Mendez MF: Secondary mania with focal cerebrovascular lesions. Am J Psychiatry 1984; 141:1084–1087Google Scholar

26 Corey-Bloom J, Sabbagh MN, Bondi MW, et al: Hippocampal sclerosis contributes to dementia in the elderly. Neurology 1997; 48:154–160Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Clark A, White CI, Manze H, et al: Primary degenerative dementia without Alzheimer pathology. Can J Neurol Sci 1986; 13:462–470Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Dickson D, Davies P, Bevona C, et al: Hippocampal sclerosis: a common pathological feature of dementia in very old (≥80 years of age) humans. Acta Neuropathol 1994; 88:212–221Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Gearing M, Mirra S, Hedreen J, et al: The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD), part X: neuropathology confirmation of the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1995; 45:461–466Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Jellinger K: Hippocampal sclerosis: a common pathological feature of dementia in very old humans. Acta Neuropathol 1994; 88:599Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Rasmusson DX, Brandt J, Steele C, et al: Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease and clinical features of patients with non-Alzheimer disease neuropathology. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1996; 10:180–188Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 Volpe B, Petito C: Dementia with bilateral medial temporal lobe ischemia. Neurology 1985; 35:1793–1797Google Scholar

33 MacLean PD: Special award lecture: new findings on brain function and sociosexual behavior, in Contemporary Sexual Behavior: Critical Issues in the 1970s, edited by Zubin J, Money J. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973, pp 53–74Google Scholar

34 Slimp JC, Hart BL, Goy RW: Heterosexual, autosexual and social behavior of adult male rhesus monkeys with medial preoptic-anterior hypothalamic lesions. Brain Res 1978; 142:105–122Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 Oomura Y, Yoshimatsu H, Aou S: Medial preoptic and hypothalamic neuronal activity during sexual behavior of the male monkey. Brain Res 1983; 266:340–343Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36 Rosler A, Witztum E: Treatment of men with paraphilia with a long-acting analogue of gonadotropin-releasing hormone. N Engl J Med 1998; 338:416–422Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 Berlin FS, Coyle GS: Sexual deviation syndromes. John Hopkins Medical Journal 1981; 149:119–125Medline, Google Scholar