Presurgical Postictal and Acute Interictal Psychoses Are Differentially Associated With Postoperative Mood and Psychotic Disorders

Abstract

The authors studied 52 patients who had undergone surgery because of intractable temporal lobe epilepsy. Investigation of postoperative psychiatric illnesses focused on psychotic disorder (293.81 and 293.82) and mood disorder (293.83) due to a general medical condition diagnosed according to DSM-IV criteria. Presurgically, two episodic psychotic syndromes, acute interictal and postictal psychosis, were defined operationally. A correlation was confirmed between presurgical acute interictal psychosis and postsurgical psychotic disorder, as well as between presurgical postictal psychosis and postsurgical mood disorder. An excellent final outcome for postoperative mood disorder in contrast to a less favorable one for psychotic disorder was also suggested.

During recent decades, with some notable exceptions,1–7 a striking lack of interest has been apparent regarding the psychiatric consequences of surgery for intractable epilepsy. This is in sharp contrast to the continuous and acknowledged emphasis on neuropsychological and neurological sequelae of epileptic surgery. This long-standing neglect seems all the more peculiar when we consider the initial intensive attention of early British neurosurgeons, such as Falconer and his colleagues, to the psychiatric status of their operated patients,8–9 as well as the high incidence of psychotic episodes among patients with medial temporal lobe epilepsy,10–14 who are now widely recognized as good candidates for epileptic surgery within the spectrum of epileptic syndromes. Fortunately, the important studies are rapidly being retrieved and supplemented by recent works.15–17 In addition to recent reports, including ours, that emphasize the importance of postoperative psychiatric follow-up, neurosurgeons are beginning to reconsider surgical indications for patients with epilepsy and psychoses.18 We believe that this recent development opens a new approach to traditional psychiatric illnesses. Epileptic mental aberrations could serve as a biological model of major psychiatric illnesses, as Trimble and his colleagues suggested long before.19 In a series of studies,17,20,21 we found that two syndromes of episodic epileptic psychoses, postictal and acute interictal psychosis, constitute definite psychopathological symptom complexes demarcated from each other. Further, our results seem to indicate that these patients are likely to develop different types of psychiatric illness after surgical intervention.17,22 Because the latter finding was preliminary, we attempted to amplify it in the present study. We believe that our conclusion could provide a fundamental framework for considering epileptic psychoses as a biological model for psychiatric illness.

METHODS

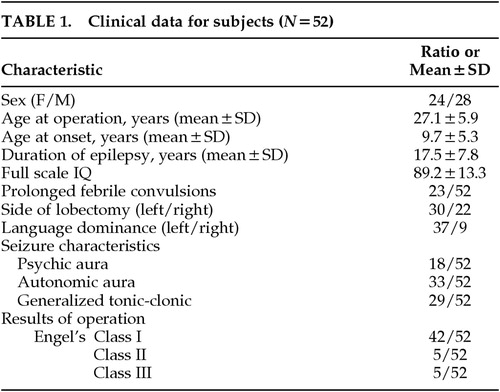

This study includes all patients (N=52) who had undergone, in the Kansai Regional Epilepsy Center, an inferior (or inferior and middle) temporal lobectomy with a hippocampo-amygdalotomy because of intractable medial temporal lobe epilepsy, with a minimum follow-up period of 2 years after surgery. Written informed consent for the surgery had been obtained after a complete and repeated description of the operation procedure and possible sequelae, including irreversible psychiatric illness, was provided to the subjects and their families. The clinical data from these subjects, including sex, age at the time of the operation, duration of epilepsy, side of the lobectomy and language dominance, full scale IQ, surgical results estimated according to Engel's classification,23 and types as well as incidence of seizures, are presented in Table 1. Language dominance was determined with an intravenous sodium amobarbital test. The duration of the postoperative follow-up was 2 to 12 years. Febrile convulsions lasting for more than 30 minutes or having transient postictal neurological signs were termed complicated febrile convulsions.

Psychotic disorder (293.81, 293.82) and mood disorder (293.83) due to a general medical condition that fulfilled the DSM-IV criteria24 were the postoperative mental illnesses examined in the present study. However, for preoperative psychotic episodes, because clinical seizures are the outstanding feature of epilepsy,25 we adhered to the traditional concept of classifying epileptic psychoses according to their temporal relationship to these events. Postictal psychosis was defined operationally as psychosis that occurs within 72 hours after the last generalized tonic-clonic seizure or cluster of complex partial seizures. All other episodes of psychosis were included in the category of acute interictal psychosis. Almost all episodes of acute interictal psychosis in the present series coincided with the absence or remarkable diminution of seizures, at least during the initial phase of the psychosis. Patients with continuous hallucinations or delusions without remission were regarded as having chronic psychosis and were excluded from the group of surgical candidates beforehand.

The research question used remained undisclosed to all of the authors throughout the period of data sampling, as this was a purely retrospective study that examined case card descriptions. We transcribed the psychiatric symptom descriptions from the case cards and then operationally judged a symptom to be present only if it was rated greater than 4 according to the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale.26 Prior to the temporal lobectomy, 10 patients had episodes of acute interictal psychosis (AIP group) and 6 experienced postictal psychoses (Post group). We added 2 patients who exhibited repetitive episodes of prolonged postictal confusion with flamboyant behavioral automatisms lasting for more than 2 hours to the Post group.

Statistical analyses were made with chi-square tests (one-tailed), using Yates' modifications for small numbers.

RESULTS

Correlation Between Preoperative and Postoperative Psychiatric Disorders

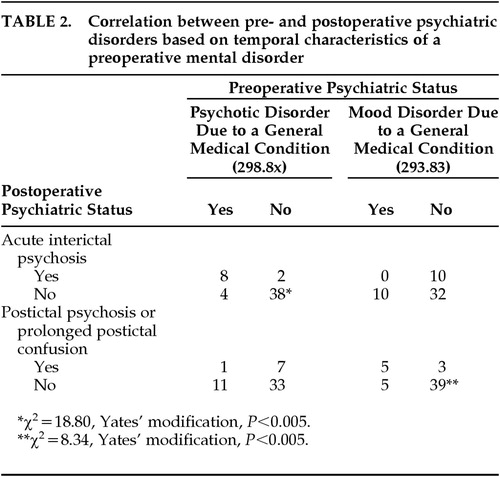

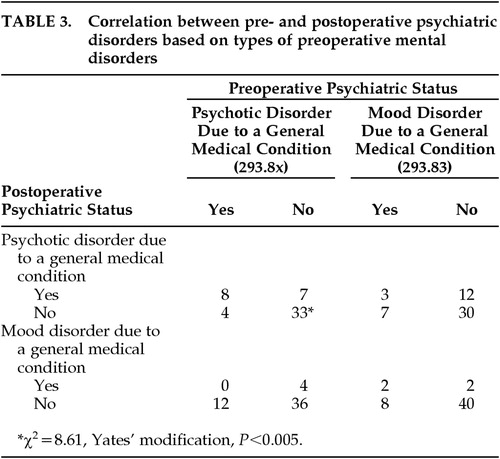

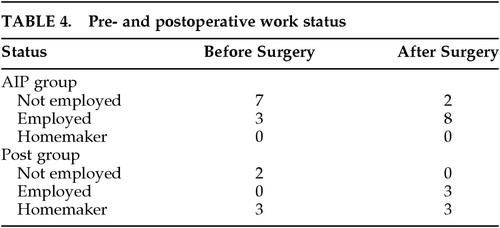

Among the 12 patients with postoperative psychotic disorders, 8 had a delusional disorder, 3 had a schizophreniform disorder, and 1 had schizophrenia according to the DSM-IV criteria. Out of the 10 patients with postoperative mood disorders, 5 had only depressive episodes, and the other 5 had manic phases (1 manic-depressive, 1 manic, 2 hypomanic, and 1 mixed episode). As summarized in Table 2, among the 10 patients in the AIP group, psychotic disorders recurred in 8 patients postoperatively. This correlation was statistically significant (Table 2). Postoperatively, mood disorders occurred in 5 of the 10 patients in the Post group. This correlation was also statistically significant (Table 2). In contrast, there were no statistically significant correlations between pre- and postoperative mood disorders as summarized in Table 3. Further, the correlation between pre- and postoperative psychotic disorder (Table 3) proved to be much looser than that between AIP and postoperative psychotic disorder. Prior to the onset of seizures, there occurred neither mood nor psychotic disorder, and no patient had both psychosis and an affective syndrome postoperatively. Following the operation, the employment status of the patients improved dramatically in both the AIP and Post groups (Table 4).

Duration of Postoperative Psychiatric Illness

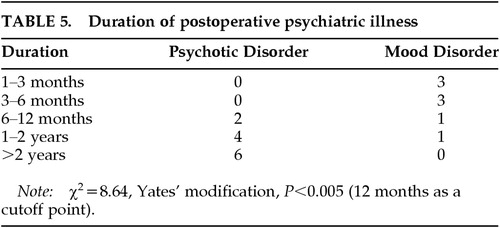

The duration of postoperative mood disorders was relatively short (2 to 17 months). They each started within 2 months and disappeared within 1 year after surgery, except for 1 patient. All of the mood disorders cleared up completely and did not recur once they had remitted. In contrast, the duration of psychotic disorders was far longer (7 months to 7 years). Moreover, in 5 of the 12 patients, the psychotic disorder is still active or becomes active episodically. These patients are continuously under antipsychotic medication as well as intensive psychotherapy, even now. In 2 patients, schizophreniform psychosis occurred even after a 5-year and a 7-year interval, respectively. When a 1-year duration was chosen as the cutoff point, the difference between mood disorders and the psychotic disorders was statistically significant (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

The proportion of patients with postoperative psychosis in our series (23%) agreed well with that in a Danish series (27%).6 In contrast, only 7% of the patients with mesial temporal sclerosis examined by Bruton1 showed postoperative schizophrenia; however, this figure apparently excluded other less severe psychotic disorders, such as delusional and schizophreniform disorders. In agreement with early as well as recent reports derived from the Maudsley series,1,3,7 full-blown mood disorders, rarely observed preoperatively, occurred in a substantial number of patients after surgery in our series. Although depressive states disclosed on various psychological rating scales were found frequently in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy,27,28 they should not be confused with full-blown mood disorders, such as major depression, diagnosed according to DSM-IV.

It has long been asserted that patients with psychotic behavior prior to surgery do not benefit from an operation.29 Indeed, presurgical psychotic behavior deteriorated or remained uninfluenced in the early series.9,13 Subsequently, at some stage, most surgical centers have excluded patients with gross mental changes from receiving surgery. A recent report of Reutens et al.,18 who operated on patients with chronic psychosis, highlighted this problem all the more sharply. Considering the excellent prognosis of patients with postoperative mood disorders, which are closely associated with postictal psychosis, it is obvious that patients with this type of mental change have a good chance of gaining great relief from a temporal lobectomy. Whether or not we should operate on patients with preoperative acute interictal psychosis remains a more complicated problem. Among the 10 patients in the present study with a preoperative history of acute interictal psychosis, psychotic disorder recurred postoperatively in more than two-thirds. This association is statistically significant. Further, 5 of the 12 patients are still in an active state of psychosis. These observations, taken together, indicate that a history of acute interictal psychosis prior to surgery, occurring without a definite relation to seizure or seizure clusters, is an obvious risk factor for the postoperative development of psychosis. However, from a different viewpoint, less than half of the patients with such a prehistory continued to have disabling psychiatric disorders that substantially impeded social adjustments. Indeed, we should be prepared to provide long-standing intensive psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy after surgery when we operate on a patient with acute interictal psychosis. However, it should be the patient's choice whether or not to take this risk.

No known previous studies have mentioned that presurgical histories of acute interictal or postictal psychoses predispose operated patients to develop different types of psychiatric illness after surgery. Our study demonstrated a close relationship between presurgical acute interictal psychosis and postoperative psychotic disorder, and between presurgical postictal psychosis and postoperative mood disorder. Although a literature search failed to reveal any directly corresponding descriptions, it is not surprising that these two types of presurgical epileptic psychosis, one with primary delusions or even schneiderian first-rank symptoms and the other with conspicuous manic or dysphoric components,20,30,31 proved to be associated with postoperative psychotic and mood disorders, respectively. In fact, there is a controversy about the neurophysiological nature of presurgical epileptic psychoses. One of the representative opinions has been given by Wolf,32 postulating that there is no substantial difference of neurophysiological basis between postictal and acute interictal psychosis. The results of the present study, however, contradict this. Clearly distinct types of psychiatric illness resulted after a temporal lobectomy as a function of acute interictal and postictal psychosis, supporting the assumption that some different neurophysiological mechanisms are involved in these epileptic psychoses. In the present study, the postoperative mood disorders represent a new pathology, while a substantial portion of the postoperative psychotic disorders could be thought of as persistent preoperative symptoms. In other words, whereas preoperative acute interictal psychoses could recur or persist after surgery, preoperative postictal psychoses could change into short-lived mood disorders.

Recently, several authors have stressed the role of the temporal lobe as a key structure in the genesis of positive symptoms of schizophrenia, although some have advocated the medial temporal structure33 and others the left superior gyrus34 in further specifying the responsible areas. In addition, even a specific reduction of glutamatergic neurotransmission in the hippocampal glutamate-mediated efferent pathways has been proposed as a possible mechanism underlying some of the clinical manifestations of schizophrenia.35 Recently, a close relationship of mood disorder with limbic structures has been also suggested. Abnormalities of limbic structures, including cingulate, amygdala, and prefrontal lesions, have been demonstrated in patients with mood disorders in functional imaging studies using positron emission tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging.36,37 Our study provides supportive evidence to theories that emphasize the role of the limbic structure in the genesis of these psychiatric illnesses. Medial temporal lobe epilepsy could provide a biological model for not only psychotic disorder,38 but also mood disorder, and could serve as a bridge between them.

|

|

|

|

|

1 Bruton CJ: The neuropathology of temporal lobe epilepsy. Maudsley Monograph No 31. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 1988Google Scholar

2 Mace CJ, Trimble MR: Psychosis following temporal lobe surgery: a report of six cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1991; 54:639-644Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Polkey CE: Effects of anterior temporal lobectomy apart from the relief of seizures. J R Soc Med 1983; 76:354-358Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Stevens JR: Psychiatric consequences of temporal lobectomy for intractable seizures: a 20-30-year follow-up of 14 cases. Psychol Med 1990; 20:529-545Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Taylor DC: Mental state and temporal lobe epilepsy: a correlative account of 100 patients treated surgically. Epilepsia 1972; 13:727-765Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Jensen I, Larsen JK: Mental aspects of temporal lobe epilepsy: follow-up of 74 patients after resection of a temporal lobe. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1979; 42:256-265Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Trimble MR: The Psychosis of Epilepsy. New York, Raven, 1991Google Scholar

8 Hill D, Pond DW, Mitchell W, et al: Personality changes following temporal lobectomy for epilepsy. J Ment Sci 1957; 103:18-27Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Falconer MA: Reversibility by temporal lobe section of the behavior abnormalities of temporal lobe epilepsy. N Engl J Med 1963; 289:451-455Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Jensen I, Larsen JK: Psychoses in drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1979; 42:948-954Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Taylor DC: Factors influencing the occurrence of schizophrenia-like psychosis in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Psychol Med 1975; 5:249-254Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Walker AE, Blumer D: Behavioral effects of temporal lobectomy for temporal lobe epilepsy, in Psychiatric Aspects of Epilepsy, edited by Blumer D. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1984, pp 295-323Google Scholar

13 Green JR, Duwberg RH, McGrath WB: Focal epilepsy of psychomotor type. J Neurosurg 1951; 8:157-172Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Penfield W: Discussion, in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy, edited by Baldwin M, Bailey P. Springfield, IL, CC Thomas, 1958, pp 484-495Google Scholar

15 Ring HA, Moriarty J, Trimble MR: A prospective study of the early postsurgical psychiatric associations of epilepsy surgery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998; 64:601-604Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Blumer D, Wahlu S, Davies K, et al: Psychiatric outcome of temporal lobectomy for epilepsy: incidence and treatment of psychiatric complications. Epilepsia 1998; 39:478-486Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Kanemoto K, Kawasaki J, Mori E: Postictal psychosis as a risk factor for mood disorders following temporal lobectomy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998; 65:587-589Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Reutens DC, Savard G, Andermann F, et al: Results of surgical treatment in temporal lobe epilepsy with chronic psychosis. Brain 1997; 120:1929-1936Google Scholar

19 Trimble MR, Koella WP: Introduction: reasons and aims of this symposium, in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy, Mania, and Schizophrenia, edited by Koella WP, Trimble MR. Basel, Karger, 1985, pp 3-8Google Scholar

20 Kanemoto K, Kawasaki J, Kawai I: Postictal psychoses: a comparison with acute interictal and chronic psychoses. Epilepsia 1996; 37:551-556Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Kanemoto K, Takeuchi J, Kawasaki J, et al: Characteristics of temporal lobe epilepsy with mesial temporal sclerosis, with special reference to psychotic episodes. Neurology 1996; 47:1199-1203Google Scholar

22 Kanemoto K, Kawasaki J, Kawai I: Psychiatric manifestations following anterior temporal lobectomy. Journal of the Japanese Epilepsy Society 1995; 13:202-210Crossref, Google Scholar

23 Engel J Jr, Van Ness PC, Rasmussen TB: Outcome with respect to epileptic seizures, in Surgical Treatment of the Epilepsies, 2nd edition, edited by Engel J Jr. New York, Raven, 1993, pp 609-621Google Scholar

24 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition. Washington DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

25 Sachdev P: Schizophrenia-like psychosis and epilepsy: the status of the association. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:325-336Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Kolakowska T: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 1976Google Scholar

27 Perini GI, Tosin C, Carraro C, et al: Interictal mood and personality disorders in temporal lobe epilepsy and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996; 61:601-605Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Kohler C, Norstrand JA, Baltuch G, et al: Depression in temporal lobe epilepsy before epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia 1999; 40:336-340Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Simmel ML, Counts S: Clinical and psychological results of anterior temporal lobectomy in patients with psychomotor epilepsy, in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy, edited by Baldwin M, Bailey P. Springfield, IL, CC Thomas, 1958, pp 530-550Google Scholar

30 Logsdail SJ, Toone BK: Postictal psychoses. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 152:246-252Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Kanner AM, Stagno S, Kotagel P, et al: Postictal psychiatric events during prolonged video-electroencephalographic monitoring studies. Arch Neurol 1996; 53:258-263Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 Wolf P: Acute behavioral symptomatology at disappearance of epileptiform EEG abnormality. Paradoxical or “forced” normalization. Adv Neurol 1991; 55:127-142Medline, Google Scholar

33 Bogaerts B: The temporolimbic system theory of positive schizophrenic symptoms. Schizophr Bull 1997; 3:423-435Crossref, Google Scholar

34 Marsch L, Harris D, Lim KO, et al: Structural magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities in men with severe chronic schizophrenia and an early age at clinical onset. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:1104-1112Google Scholar

35 Tamminga C: Glutamatergic aspects of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 37(suppl):12-15Google Scholar

36 Soares JC, Mann JJ: The functional neuroanatomy of mood disorders. J Psychiatr Res 1997; 31:393-432Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 Kennedy SH, Javanmard M, Vaccarino FJ: A review of functional neuroimaging in mood disorders: positron emission tomography and depression. Can J Psychiatry 1997; 42:467-475Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38 Roberts GW, Done DJ, Bruton C, Crow TJ: A “mock-up” of schizophrenia: temporal lobe epilepsy and schizophrenia-like psychosis. Biol Psychiatry 1990; 28:127-143Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar