Are Late-Onset Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders Neurodegenerative Conditions?

Abstract

Some investigators assert that emergence of schizophrenia spectrum disorders in mid- to late life (LOSD, i.e., onset after age 45) reflects neurodegenerative processes. The authors examined 1- and 2-year changes among 37 outpatients with LOSDs on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Mattis Dementia Rating Scale, compared with 69 patients having earlier-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders (EOSD), 67 having Alzheimer's disease (AD) with psychosis, 72 having AD with baseline MMSE scores ≥24, and 56 normal comparison subjects (NCs). Cognitive changes among LOSD patients were similar to those in EOSD patients and NCs, whereas the AD groups had greater declines. Results support viewing LOSDs as static encephalopathies.

In contrast to Kraepelin's notion of schizophrenia as a “dementia praecox” with a progressively deteriorating course, the neuropathology underlying schizophrenia generally appears to be nonprogressive, and largely neurodevelopmental in origin.1–4 However, some investigators have suggested that when schizophrenia spectrum disorders first appear in mid- to late life (LOSDs; or what in Europe is referred to as “paraphrenia”), such conditions are likely to reflect neurodegenerative processes emerging close to the time of illness and thus should be distinguished from “real” (earlier onset) schizophrenia spectrum disorders (EOSDs).5,6 One type of evidence that would support the latter view would be the presence of progressive cognitive decline in LOSD patients similar to that seen in patients with other neurodegenerative disorders.7

Some studies of older patients with early-onset schizophrenia (i.e., prior to age 45) in long-term institutions have suggested a higher than normal rate of cognitive decline.8 However, the vast majority of contemporary older patients with schizophrenia are not institutionalized.9 Studies of noninstitutionalized schizophrenia patients indicate no evidence of progressive cognitive decline.10 For example, in a recent longitudinal study from our center in which patients received a modified Halstead-Reitan neuropsychological battery over several years of follow-up, there was no evidence of cognitive decline among older or younger outpatients with schizophrenia.11

In the present study, we examined stability of cognitive performance among patients with LOSD on the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)12 and the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (DRS).13 Focus on these two measures permitted a comparison of data from our LOSD patients with data from patients having probable Alzheimer's disease (AD), a prototypic neurodegenerative disorder; patients of similar age with schizophrenia spectrum disorders whose onset of illness occurred prior to age 45 (EOSDs); and a demographically comparable group of normal comparison subjects (NCs). We hypothesized that the pattern of longitudinal change in MMSE and DRS scores among the LOSD patients would differ significantly from that in AD but would be similar to that in EOSDs and NCs.

The present sample partially overlapped with a prior report from our center,11 but there are several differences worth noting. The focus of the prior study was on cognitive stability among schizophrenia patients of all age groups, not on LOSD, but the prior study did include 24 patients with late-onset schizophrenia. In the present report we have expanded the size of the LOSD sample to 37 patients with late-onset schizophrenia spectrum conditions. Also, neither the MMSE nor the DRS was included in the prior report. Because we also had longitudinal data on these measures for patients with probable AD, the focus on the MMSE and DRS in the present study permitted a direct comparison between the rates of cognitive stability/change in LOSD patients and those in patients with AD. The previous report did not include AD patients.

METHODS

Subjects

Participants included 37 community-dwelling patients with LOSDs (i.e., age at onset ≥45 years; 29 schizophrenia, 1 schizoaffective disorder, 7 delusional disorder) for whom we had archival data for at least one baseline and annual retest with the MMSE and/or the DRS. Results from the LOSD group were compared with those of 71 middle-aged and older patients with schizophrenia or related conditions whose onset of illness was prior to age 45 (EOSDs; 57 schizophrenia, 12 schizoaffective disorder, 2 delusional disorder); 67 patients with probable AD with psychosis (AD-PSY); 72 patients with probable AD with relatively mild cognitive impairment (AD-COG; MMSE total scores ≥24); and 56 NCs. This report involves secondary analyses of existing data collected by two research centers at the University of California, San Diego: the UCSD Clinical/Intervention Research Center for the Study of Late-Life Psychoses (IRC-LLP; where the LOSD, EOSD, and NCs were participants) or the UCSD Alzheimer Disease Research Center (ADRC; where the AD-PSY and AD-COG patients were participants), and many of the subjects have contributed data to prior reports.11,14–17

The 56 NCs were selected from a larger pool of 97 NCs in the database who had had repeat MMSE and/or DRS examination data. This selection of NC data was conducted (without examining the scores on the cognitive measures) by dropping potential NCs from the pool so that the range and mean (or proportions) of the NC and LOSD groups were roughly comparable for age, education, gender, and ethnicity. Because the MMSE and DRS were not always given to the same subjects, the sample sizes for analyses involving two MMSE assessments were as follows: NC=56, LOSD=34, EOSD=70, AD-PSY=63, and AD-COG=72. The sample sizes for analyses involving two DRS assessments were NC=38, LOSD=29, EOSD=49, AD-PSY=61, and AD-COG=66.

Diagnostic status for IRC-LLP participants (NCs and LOSD and EOSD patients) was established with a structured clinical interview (SCID) using DSM-III-R or DSM-IV criteria.18,19 Per DSM-III-R,20 “late onset” was defined as onset of prodromal symptoms of psychosis after age 45. Medical history and neurological and other physical examinations were completed by trained Geriatric Psychiatry Fellows and, when indicated by results of the physical examination or history, included appropriate lab workups including blood counts, thyroid hormones, and/or brain CT or MRI. Subjects with medical conditions likely to affect central nervous system functioning, as well as those meeting DSM-III-R or DSM-IV criteria for current substance abuse or dependence, were excluded.

The patients in the AD-PSY group were identified through a review of data from patients in the UCSD ADRC with probable AD (as diagnosed by two senior neurologists per NINCDS-ADRDA criteria)21 to identify patients who had psychosis of AD22 at their baseline evaluation. Psychosis was defined as the presence of delusions and/or hallucinations not due to any other known cause (e.g., schizophrenia, delirium, drug toxicity) and not reflective of mere confabulation due to memory deficits. The AD-COG group was a second (nonoverlapping) group of AD patients with relatively mild baseline cognitive impairment whose MMSE scores were 24 or above, identified from the remaining pool of subjects in the ADRC database.

Cognitive Measures

Cognitive measures included the MMSE12 and DRS.13 Scores on the MMSE range from 0 to 30. The DRS yields a total score (range 0 to 144) and five subscale scores: Attention (range 0 to 37), Initiation/Perseveration (range 0 to 37), Construction (range 0 to 6), Conceptualization (range 0 to 39), and Memory (range 0 to 25). Higher scores on the MMSE and DRS indicate better cognitive performance.

Procedures

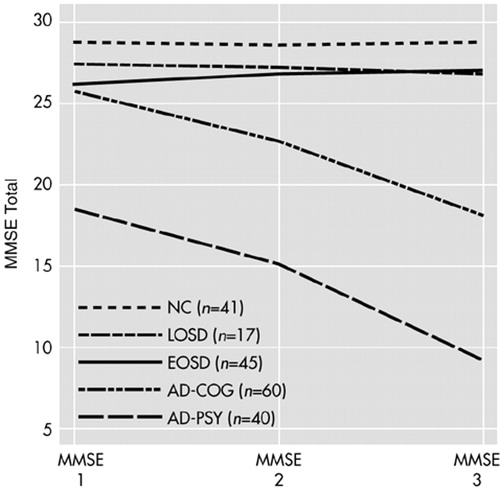

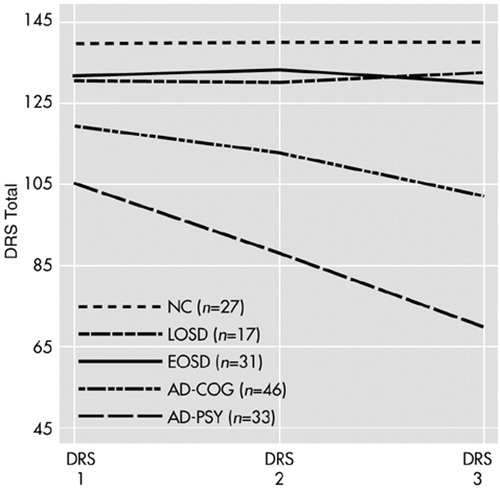

Subjects completed the MMSE and/or the DRS at baseline (MMSE 1 and DRS 1) and at a follow-up visit (MMSE 2 and DRS 2) approximately 1 year later. For a subset of the participants, we also had MMSE and/or DRS data for yet another annual follow-up (MMSE 3 and DRS 3). MMSE 3 data were available for 41 NCs, 17 LOSD patients, 45 EOSD patients, 40 AD-PSY patients, and 60 AD-COG patients. DRS 3 data were available for 27 NCs, 17 LOSD patients, 31 EOSD patients, 33 AD-PSY patients, and 46 AD-COG patients.

Statistical Analyses

Differences in the age, education, and test-retest intervals among the five groups were evaluated with one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and follow-up pairwise comparisons using Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference procedure (HSD). Differences in gender and ethnicity were compared with Pearson's chi-square test. The MMSE and DRS scores among the five groups were compared with repeated-measures ANOVAs, with age as a covariate. To determine whether the changes in the MMSE and DRS scores among the LOSD patients differed from those in each of the other four groups, we also conducted planned pairwise comparisons of the LOSD group with each of the other four groups using repeated-measures ANOVAs. For the MMSE and DRS total scores, and the DRS subscale scores, we also examined group differences in the magnitude of change by use of one-way ANOVAs with follow-up pairwise comparisons using Tukey's HSD. Significance for all analyses was defined as P<0.05 (two-tailed, where applicable).

RESULTS

Although the retests were scheduled annually, the mean retest intervals among the LOSD patients were slightly longer than the corresponding retest intervals among the other groups. For example, the mean retest interval between MMSE 1 and MMSE 2 among LOSD patients was 17.2 (SD=9.8) months, whereas the intervals for the other groups were all between 12.6 and 13.0 months (all P<0.05). Please note, however, that because of these longer retest intervals, the LOSD patients had an even longer duration over which to manifest possible cognitive decline.

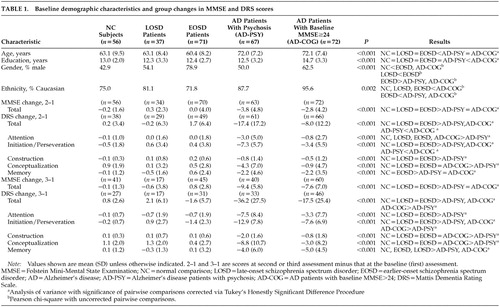

The baseline demographic characteristics of the NCs, LOSD patients, EOSD patients, and the two AD patient groups are listed in Table 1. Notably, the AD patient groups were significantly older than the NC, LOSD, and EOSD groups. Thus, age was used as a covariate in the repeated-measures ANOVAs.

MMSE Changes

The repeated-measures ANOVA for MMSE scores at baseline (first) and second assessments (MMSE 1 and MMSE 2, respectively) showed significant group effects (F=129.63, df=4 , 289, P<0.001), significant time effects (F=33.00, df=1 , 290, P<0.001), and a significant group-by-time interaction (F=14.69, df=4 , 290, P<0.001). Age was not a significant covariate (F=0.20, df=1 , 289, P=0.659). Follow-up analyses of the group-by-time interaction with the planned pairwise repeated-measures ANOVAs revealed no significant group-by-time effects when LOSD patients were compared with NCs (F=1.65, df=1,88, P=0.203) or with EOSD patients (F=0.18, df=1 ,102 , P=0.673). In contrast, there were significant group-by-time effects comparing MMSE performance over time in the LOSD group relative to that in the AD-PSY group (F=22.16, df=1,95, P<0.001) and the AD-COG group (F=16.82, df=1 , 104, P<0.001), wherein each of the AD patient groups showed significantly greater declines in MMSE scores than did the LOSD patients. The AD-PSY patients' mean MMSE total score dropped from 18.6 (SD=4.9) at baseline to 14.8 (SD=5.6) at the next assessment, and the AD-COG patients' mean MMSE total score dropped from 25.7 (SD=1.3) to 22.9 (SD=4.3); whereas the corresponding values for LOSD patients were 27.2 (SD=2.4) at baseline and 27.6 (SD=2.2) at the next assessment. Similar results were observed when the groups were limited to subjects ages 60 to 69 years; that is, there was no decline from MMSE 1 to MMSE 2 among the NCs (n=22; mean [SD]: MMSE 1=29.0 [1.1], MMSE 2=29.0 [1.1]), the LOSD patients (n=13; MMSE 1=27.1 [2.5], MMSE 2=27.8 [1.3]), or the EOSD patients (n=28; MMSE 1=26.5 [3.0], MMSE 2=26.8 [3.0]). In contrast, among AD patients in this age group, there was a decline in both the AD-PSY group (n=16; MMSE 1 =19.6 [3.3], MMSE 2=14.9 [5.1]) and the AD-COG group (n=13; MMSE 1=25.6 [1.3], MMSE 2=21.9 [4.2]); repeated-measures ANOVA indicated that these differences represented a significant group-by-time interaction (F=12.35, df=4,87, P<0.001). Similar results were observed when the repeated-measures ANOVA was limited to subjects ages 70 to 79, wherein the mean (SD) MMSE 1 and MMSE 2 scores were 28.7 (1.1) and 28.2 (1.2) for the NCs (n=16); 27.7 (2.5) and 26.7 (2.7) among LOSD patients (n=9); 25.3 (3.7) and 25.4 (2.6) among EOSD patients (n=11); 18.4 (5.5) and 14.0 (5.9) among AD-PSY patients (n=33); and 25.9 (1.4) and 23.0 (4.6) among AD-COG patients. Again, the latter two differences represented a significant group-by-time interaction (F=4.29, df=4 , 109, P<0.003).

Repeated-measures ANOVA, with age as a covariate, using the MMSE data from those subjects in each of the five groups for whom we had MMSE data for three time points revealed a similar pattern, i.e., the overall repeated-measures ANOVA yielded significant group effects (F=110.91, df=4 , 197, P<0.001), significant time effects (F=60.17, df=2 , 396, P<0.001), and a significant group-by-time interaction (F=29.41, df=8 , 396, P<0.001). Again, age was not a significant covariate (F=1.36, df=1 , 197, P=0.245). Pairwise comparisons revealed no significant group-by-time interactions in comparing the LOSD patients with the NCs (F=0.59, df=2 , 112, P=0.555) or EOSD patients (F=1.82, df=2 , 120, P=167), whereas the AD-PSY and AD-COG groups showed significantly greater declines in MMSE performance relative to the LOSD (F=23.65, df=2 , 110, P<0.001, and F=12.55, df=2 , 150, P<0.001, respectively), as well as showing greater declines relative to the EOSD and NC groups (all P<0.001). The changes from MMSE 1 through MMSE 3 are also illustrated in Figure 1 for those subjects with all three data points.

To examine the possibility that the 17 LOSD patients with MMSE 3 data represented a biased subsample of the larger LOSD group, we also compared the characteristics of these 17 LOSD patients with all three MMSE assessments to the characteristics of the remainder of the LOSD patients. We found that the mean (and SD) change from MMSE 1 to MMSE 2 was a drop of 0.2 (2.3) points among the LOSD patients with MMSE 1, 2, and 3, versus a mean increase of 0.8 (2.3) points among those LOSD patients lacking MMSE 3 data. This difference was not significant (t=1.26, df=32, P=0.216). There were also no significant differences between these two groups in age (t=1.17, df=35, P=0.248), education (t=0.65, df=35, P=0.522), or baseline MMSE score (MMSE 1; t=–0.96, df=35, P=0.345). There was a trend toward a higher proportion of men among the LOSD patients with MMSE 3 data (70.6% vs. 40.0%, n=37; χ2=3.46, df=1, P=0.063).

DRS Changes

As with the MMSE results, analyses of the LOSD patients' DRS scores over time revealed no indication of cognitive decline. The repeated-measures ANOVA for DRS 1 to DRS 2 indicated the presence of significant group effects (F=90.80, df=4 , 237, P<0.001), significant time effects (F=38.36, df=1 , 238, P<0.001), and a significant group-by-time interaction (F=25.82, df=4 , 238, P<0.001). Age was not a significant covariate (F=0.44, df=1 , 237, P=0.509). Planned follow-up comparisons revealed a significant group-by-time interaction comparing longitudinal DRS performance among the LOSD patients relative to the AD-PSY patients (F=27.20, df=1,88, P<0.001), and to the AD-COG patients (F=10.61, df=1,93, P=0.002). Inspection of the mean (and SD) scores revealed that the mean DRS total score among the AD-PSY patients dropped from 103.8 (17.0) at DRS 1 to 86.5 (22.9) at DRS 2, and among the AD-COG patients it dropped from 120.1 (8.9) at DRS 1 to 112.0 (16.0), whereas the corresponding values for LOSD patients were 132.7 (10.8) and 132.5 (10.7). There were no significant group-by-time interactions when the LOSD patients' DRS performance was compared with that of the NCs (F=0.08, df=1,65, P=0.784) or the EOSD patients (F=1.54, df=1,76, P=0.219). Similar results were observed when the repeated-measures ANOVA was limited to subjects ages 60 to 69, wherein the mean (and SD) DRS 1 and DRS 2 total scores were 141.3 (2.3) and 141.3 (3.1) for NCs (n=18); 132.2 (16.0) and 131.8 (15.8) among LOSD patients (n=10); 134.2 (16.0) and 133.4 (9.0) among EOSD patients (n=22); 108.5 (9.9) and 86.4 (25.4) among AD-PSY patients (n=17); and 120.3 (8.0) and 111.2 (11.6) among AD-COG patients (n=11), which yielded a significant group-by-time interaction (F=10.66, df=4,73, P<0.001). Among those ages 70 to 79, the mean (and SD) DRS 1 and DRS 2 scores were 139.9 (3.1) and 140.5 (3.0) among the NCs (n=12); 132.7 (6.9) and 132.2 (7.3) among the LOSD patients (n=9); 123.0 (13.0) and 129.1 (7.6) among the EOSD patients (n=7); 100.0 (20.8) and 81.8 (23.8) among the AD-PSY patients (n=30); and 120.4 (9.5) and 111.5 (18.4) among the AD-COG patients (n=42), which represented a significant group-by-time interaction (F=8.92, df=4,95, P<0.001).

The mean DRS total scores for the subset of subjects with DRS assessments for each of the three time points (DRS 1, DRS 2, and DRS 3) are illustrated in Figure 2. A repeated-measures ANOVA for DRS scores at these three time points revealed significant group effects (F=63.03, df=4 , 148, P<0.001), significant time effects (F=31.73, df=2 , 298, P<0.001), and a significant group-by-time interaction (F=16.57, df=8 , 298, P<0.001). Age was not a significant covariate (F=0.84, df=1 , 148, P=0.361). Paralleling the findings for the entire sample from DRS 1 to DRS 2, planned follow-up comparisons revealed that the significant group-by-time interaction was attributable to the consistent decline in DRS performance among the two AD groups, whereas there were no significant group-by-time interactions in comparing changes on the DRS among the LOSD patients relative to the NCs or the EOSD patients.

Cognitive Stability in Recent-Onset LOSD Patients

To investigate the possibility that onset of illness among LOSD patients might reflect a time-limited neurodegenerative process, and that cognitive change might be present mostly among LOSD patients with recent onset of illness, we also examined the magnitude of change scores among those LOSD patients whose baseline duration of illness was one year or less. Even in this subgroup, however, the mean change scores were positive (suggesting improved performance): mean (and SD) for MMSE 2 minus MMSE 1 (n=9) was 1.4 (1.9); for MMSE 3 minus MMSE 1 (n=9), 0.6 (0.9); for DRS 2 minus DRS 1 (n=8), 0.1 (4.1); and for DRS 3 minus DRS 1, 1.8 (4.4).

DISCUSSION

Consistent with our hypotheses, this study revealed a stable pattern of performance on two widely used dementia screening measures among middle-aged and older LOSD patients. This pattern was equivalent to that observed among the NCs as well as the EOSD patients, and significantly different from the declines observed among the AD-PSY and AD-COG patients. The findings of cognitive stability are consistent with the larger schizophrenia literature (which has focused predominantly on patients whose onset of illness occurred in adolescence or early adulthood),10 and with a recent report from our center using a different cognitive test battery.11

The present results provide no evidence of a progressive deterioration in cognitive functioning among community-dwelling LOSD patients. Acquired brain lesions clearly can mimic primary psychoses,23–25 and it remains possible that late onset of schizophrenia-like syndromes reflects nonprogressive neurological lesions acquired in late life, but no evidence of focal neurologic impairment was evident during clinical examinations or brain imaging of our late-onset schizophrenia patients,17 and no such focal impairments have been documented in the late-onset schizophrenia literature.

Several limitations to the present study should be noted. The follow-up period for the primary comparisons was limited to 1 or 2 years, and data for the second follow-up (MMSE 3 and DRS 3) were available for only a subset of the sample. Studies with longer follow-up periods could reveal that LOSD patients experience a very slow cognitive decline that is obscured by normal practice effects when observed over shorter periods. Few of the LOSD patients were currently on atypical antipsychotic medications (none were on clozapine or olanzapine, and only two were on risperidone at the time this study was conducted), but it is conceivable that treatment with such medications could mask cognitive declines in some patients when observed for only a few years.26 It is also possible that subtle cognitive declines would be observed on tests more sensitive to the cognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia than are the MMSE and DRS. Furthermore, because our LOSD sample was composed of clinically stable community-dwelling outpatients, the present results may not generalize to chronically institutionalized samples.8 On the other hand, the majority of contemporary older patients with schizophrenia reside in the community, rather than in institutional settings.9 Also, the mean age in both AD groups was approximately 72 years, whereas most of the LOSD patients (70%), as well as NCs and EOSD patients, were under age 70. It is possible that greater cognitive decline would be observed in an older LOSD sample, but age was not a significant covariate in the repeated-measures ANOVAs, and when the analyses were limited to patients in the subset in their 60s, and again among those in their 70s, the same pattern of results emerged.

In addition, the present study does not rule out the possibility that LOSDs (or EOSDs) reflect time-limited neurodegenerative processes occurring around the time of symptom onset. Indeed, we presume that the onset of symptoms must be associated with some parallel changes in brain activity. Nonetheless, even among the small subset of LOSD patients whose onset of symptoms was within one year or less preceding their baseline evaluation, we observed no groupwise tendency toward decline in cognitive performance. Furthermore, even if such time-limited brain changes could be documented, they may also occur with onset of symptoms among patients with EOSDs—so it would not be a basis for distinguishing between early and late-onset forms.

Despite the above limitations, the current results are important in demonstrating that the cognitive deficits associated with LOSDs are very stable, in contrast to the prototypic and quite salient cognitive declines associated with AD. The rate of decline observed among the AD groups in the present sample appears to be consistent with that reported in the literature.27,28 Thus, the onset of schizophrenia-like syndromes in mid- to late life does not appear to be a mere by-product of a dementing disorder such as AD. This conclusion is consistent with the findings from studies by the Mount Sinai research group that examined chronically institutionalized elderly schizophrenia patients. Their samples were not composed of late-onset patients, but many of these patients had reportedly experienced progressive cognitive declines.29,30 These investigators found that the pattern of cognitive deficits of such patients was distinct from that associated with AD, and, moreover, their postmortem neuropathological studies indicated that the prevalence of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles was no different from that of age-matched healthy control subjects.29

It may be that late onset of schizophrenia-like symptoms represents essentially the same disease as the early-onset form but manifests late in the context of various, as yet unknown, protective factors; another possibility is that LOSDs are a milder form of EOSDs. Given the lack of observable progressive decline in this and other studies, it seems incumbent on those who assert that late-onset schizophrenia and related disorders are primarily neurodegenerative conditions to specify the nature of the neurodegenerative processes and to show their distinction from those processes associated with onset of schizophrenia and other primary psychoses in young adulthood. Although LOSDs do not appear to be a form of AD, subcortical dementias such as Huntington's disease (HD) and Parkinson's disease (PD) could represent better neurodegenerative models of LOSDs. These conditions are associated with at least gradual cognitive declines that can be observed even with screening measures such as the MMSE, but the presence and rate of cognitive decline tend to vary widely.31,32 Further longitudinal studies of LOSD patients, using comparison groups of HD and PD patients and incorporating other measures of brain functioning (such as functional neuroimaging), may prove helpful in identifying any subgroups with progressive subcortical degeneration among LOSD patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grants MH01452, MH49671, MH43693, and MH59101; National Institute on Aging Grants AG12674 and AG05131; and the Department of Veterans Affairs. A preliminary version of this project was presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry (Miami, FL), March 2000.

FIGURE 1. Longitudinal performance on the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) among subjects with three assessments, including normal comparison subjects (NC) and patients with late-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorder (LOSD), earlier-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorder (EOSD), probable Alzheimer's disease with mild baseline cognitive deficits (AD-COG), and probable Alzheimer's disease with psychotic features (AD-PSY).

FIGURE 2. Longitudinal performance on the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (DRS) among subjects with three assessments, including normal comparison subjects (NC) and patients with late-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorder (LOSD), earlier-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorder (EOSD), probable Alzheimer's disease with mild baseline cognitive deficits (AD-COG), and probable Alzheimer's disease with psychotic features (AD-PSY).

|

1 Green MF: Schizophrenia From a Neurocognitive Perspective: Probing the Impenetrable Darkness. Boston, Allyn and Bacon, 1998Google Scholar

2 Heyman I, Murray RM: Schizophrenia and neurodevelopment. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1992; 26:143-146Medline, Google Scholar

3 Nasrallah HA: Neurodevelopmental pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1993; 16:269-280Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Palmer BW, Jeste DV: Neurodevelopmental theories of schizophrenia: application to late-onset schizophrenia. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 1996; 38:13-22Medline, Google Scholar

5 Castle DJ, Murray RM: The epidemiology of late-onset schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1993; 19:691-700Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Murray RM, O'Callaghan E, Castle DJ, et al: A neurodevelopmental approach to the classification of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:319-332Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Salmon DP, Thal LJ, Butters N, et al: Longitudinal evaluation of dementia of the Alzheimer type: a comparison of 3 standardized mental status examinations. Neurology 1990; 40:1225-1230Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Harvey PD, Parrella M, White L, et al: Convergence of cognitive and adaptive decline in late-life schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1999; 35:77-84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Cohen CI, Cohen GD, Blank K, et al: Schizophrenia and older adults, an overview: directions for research and policy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000; 8:19-28Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Rund BR: A review of longitudinal studies of cognitive functions in schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Bull 1998; 24:425-435Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Heaton RK, Gladsjo JA, Palmer BW, et al: Stability and course of neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:24-32Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189-198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Mattis S: Dementia Rating Scale. Odessa, FL, Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc., 1973Google Scholar

14 Paulsen JS, Salmon DP, Thal LJ, et al: Incidence of and risk factors for hallucinations and delusions in patients with probable AD. Neurology 2000; 54:1965-1971Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Jeste DV, Harris MJ, Krull A, et al: Clinical and neuropsychological characteristics of patients with late-onset schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:722-730Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Jeste DV, McAdams LA, Palmer BW, et al: Relationship of neuropsychological and MRI measures with age of onset of schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998; 98:156-164Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Symonds LL, Olichney JM, Jernigan TL, et al: Lack of clinically significant structural abnormalities in MRIs of older patients with schizophrenia and related psychoses. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1997; 9:251-258Link, Google Scholar

18 First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorder-Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). New York, Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1995Google Scholar

19 Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, et al: User's Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

20 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed., revised. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1987Google Scholar

21 McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al: Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group. Neurology 1984; 34:939-944Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Jeste DV, Finkel SI: Psychosis of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias: diagnostic criteria for a distinct syndrome. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000; 8:29-34Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Breitner J, Husain M, Figiel G, et al: Cerebral white matter disease in late-onset psychosis. Biol Psychiatry 1990; 28:266-274Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Jeste DV, Palmer B: Secondary psychoses: an overview. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry 1998; 3:2-3Medline, Google Scholar

25 Lesser IM, Miller BL, Boone KB, et al: Brain injury and cognitive function in late-onset psychotic depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1991; 3:33-40Link, Google Scholar

26 Harvey PD, Keefe RS: Studies of cognitive change in patients with schizophrenia following novel antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:176-184Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Clark CM, Sheppard L, Fillenbaum GG, et al (the CERAD investigators): variability in annual Mini-Mental State Examination score in patients with probable Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurology 1999; 56:857-862Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Galasko DR, Gould RL, Abramson IS, et al: Measuring cognitive changes in a cohort of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Stat Med 2000; 19:1421-1432Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Davidson M, Harvey P, Welsh KA, et al: Cognitive functioning in late-life schizophrenia: a comparison of elderly schizophrenic patients with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1274-1279Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Purohit DP, Haroutunian V, Powchik P, et al: Alzheimer disease and related neurodegenerative diseases in elderly patients with schizophrenia: a postmortem neuropathologic study of 100 cases. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:205-211Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Folstein SE, Brandt J, Folstein MF: Huntington's disease, in Subcortical Dementia. Edited by Cummings JL. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990, pp 87-107Google Scholar

32 Bayles KA, Tomoeda CK, Wood JA, et al: Change in cognitive function in idiopathic Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 1996; 53:1140-1146Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar