Delirium in Children and Adolescents

Abstract

Rarely reported in pediatric patients, the characteristic symptoms and course of delirium are well known in adults. This retrospective study was undertaken to describe the clinical presentation, symptoms, and outcome of delirium in children and adolescents. Eighty-four patients age 6 months to 18 years were identified with delirium, from 1,027 consecutive psychiatric consultations during a 4-year period. Mortality was high (20%), and length of stay was prolonged. Symptoms of psychosis and disorientation were less characteristic, but overall the presentation and course of delirium were similar to adults, and the current Diagnostic and Standard Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) criteria were found applicable in the pediatric population.

Delirium is a nonspecific neuropsychiatric disorder that indicates global encephalopathic dysfunction in seriously ill patients. The clinical presentation of delirium has been well described in elderly patients during the process of developing diagnostic criteria for delirium1 and formulating instruments to aid in differentiating delirium from other cognitive disorders.2 Delirium results from disturbance of higher cortical centers that can be caused by a variety of conditions. It is characterized by diffuse cognitive dysfunction, perceptual disturbances, altered sleep-wake cycle, thought and language disturbance, altered mood and affect. Symptom onset is characteristically acute and intensity of symptoms fluctuates for the duration of the delirium.3 Delirium is often unrecognized, overlooked, or misdiagnosed by physicians, and the fluctuating nature of delirium further confounds the diagnosis.4

Delirium has been generally neglected in younger populations. It has not been reported in a group of pediatric patients since 1980,5 and there are no specific diagnostic criteria for children and adolescents. The following study was undertaken to address this deficiency and describe the clinical presentation, symptoms, and outcome of delirium in children and adolescents.

METHODS

All cases seen by the psychiatric consultation-liaison service at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles from April 16, 1991 through December 31, 1995 were reviewed, and patients with delirium based on the DSM-IIIR criteria were identified.6 The clinical presentation and course of the cases were summarized, noting the underlying cause of delirium, sex and age of the child, pharmacologic and environmental interventions provided, length of hospitalization, and outcome. The underlying disorder associated with delirium in these cases was classified into eight clinical diagnostic categories: infectious, drug-induced, autoimmune, posttransplant, postoperative, posttraumatic, neoplastic, and organ failure. The presence or absence of specific symptoms of impaired attention, impaired concentration, disorientation, hallucinations, delusions, sleep disturbance, altered level of consciousness, confusion, impaired responsiveness, impaired memory, exacerbation at night, irritability, affective lability, agitation, apathy, and anxiety was noted in each patient.

Statistical evaluation of data for these clinical and diagnostic features included t tests for differences in means, Kruskal-Wallis tests for differences in medians, and correlation coefficients to evaluate associations between variables. Only correlations of 0.6 or greater are reported.

RESULTS

There were 84 cases of delirium identified from 1,027 consecutive psychiatric consultations. They ranged in age from 6 months to 18 years, with a slight male predominance of 45 males (54%) and 39 females (46%). The average age was 10.4 years (standard deviation 5 years) and the median age was 11 years.

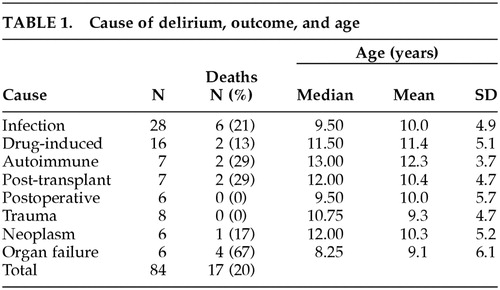

The most common cause of delirium was infection (n = 28), including viral, bacterial, fungal, and parasitic agents, usually with central nervous system involvement. (Table 1) Medication-related delirium (n = 16) was found with a variety of drugs, including anticholinergic agents, opioids, and others. Delirium was found in patients with autoimmune disorders (n = 7), including systemic lupus erythematosus and periarteritis nodosa. Delirium was seen following kidney, lung, heart and bone marrow transplant (n = 7), postoperatively (n = 6), and after serious trauma (n = 8). Children with neoplasia (n = 6), usually leukemia, lymphoma or central nervous system tumors, were at risk for delirium related to sepsis, multiple medications, or their underlying malignancy. Delirium in the organ failure category (n = 6) included patients dying with multiple organ, respiratory, or cardiac failure. Delirium in infants was seen postoperatively or due to excess anticholinergic medication, sepsis, or trauma. There was no significant difference in mean and median age for cases of delirium based on the diagnostic category.

Overall, mortality was high (20%), probably reflecting the degree of severity of the underlying illness. There were 17 deaths in this group of 84 patients. (Table 1) Mortality was higher for patients with autoimmune disorders (29%) and following transplant (29%) and highest in the organ failure group (67%). In contrast, there were no deaths in the group of patients with delirium following surgery or after serious trauma.

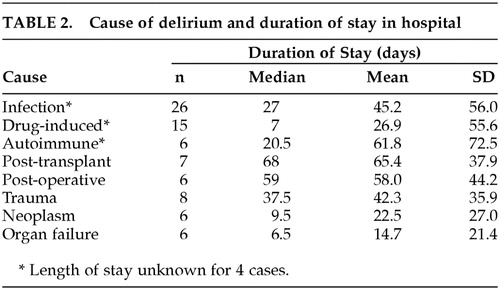

Patients with delirium were very ill, and length of hospitalization was long (mean: 41 days, range: 1 to 255 days), probably reflecting the severity of the underlying disease. (Table 2) While there was no significant difference in mean duration of hospital stay for the different categories of delirium, the median duration of hospital stay was significantly different (p = 0.019), ranging from a median of 6.5 days for cases with delirium associated with organ failure (who were the patients with the highest mortality) to 68 days for cases with posttransplant delirium.

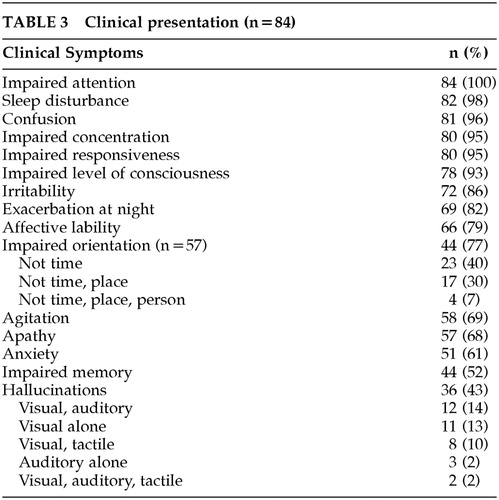

Symptoms of delirium in this pediatric series were consistent with descriptions of delirium in adults. Impaired attention was found in every patient. (Table 3) Impaired attention in infants and toddlers was identified by difficulty in engaging them, and in older children and adolescents, problems with attention appeared similar to those of adults with distractibility or inability to focus on one subject or activity. Defining attention as the ability to engage and focus mental processes, concentration represents the capacity to sustain attention to answer questions or perform mental operations.7 Poor concentration, confusion, and impaired responsiveness were common. (Table 3)

Disorientation was more difficult to evaluate in younger children. Orientation to time was not asked of the youngest patients who have little sense of time. Young, verbal children were expected to be able to answer questions of orientation to person and place, and these questions were useful in evaluating most children. Because of these limitations of age and ability, data on orientation were evaluated for 57 of 84 patients and were found to be abnormal in 44 patients. (Table 3)

Affective lability and anxious or irritable mood were found in the majority of delirious children and adolescents. Impaired psychomotor activity was common, with apathy or agitation found in similar frequency. More agitation and behavioral problems were reported at night, and sleep disturbance was found in most of the patients. (Table 3) Perhaps because these factors describe similar and related phenomena, correlations greater than 0.6 were found between agitation and irritability (r = 0.612), and agitation and liability (r = 0.719).

Confusion and misidentification were seen, but specific perceptual disturbances of derealization and depersonalization were not. Organized delusions were rare. Hallucinations were noted in 36 children, and most of those were visual hallucinations alone or visual and auditory hallucinations together. (Table 3)

Altered level of consciousness was seen more often in younger patients than in older patients. The median age of cases with altered levels of consciousness was significantly different from the median age of cases without altered levels of consciousness (10.5 years versus 16 years) (p = 0.011).

Problems with memory were not common overall and seemed to be more often identified in relatively older patients. Impaired memory was found in half of the cases, and the median age of cases with impaired memory was older than the median age of cases without impaired memory (12 years versus 9.5 years) (p = 0.050).

The treatment of delirium must be primarily treatment of the underlying condition that caused it, but environmental and psychopharmacologic interventions were also used. The nursing staff and family members were advised to provide frequent reassurance and reorientation for all the children. Antipsychotic medications were effective for sleep disturbance, hallucinations, agitation, or confusion. Most patients received high potency antipsychotics (e.g., haloperidol 18, droperidol 1) orally or intravenously, and a few received low potency agents (e.g., thioridazine 2, chlorpromazine 1) orally. Low dose intravenous haloperidol was most often used, starting at 0.25 mg. qhs., and rarely exceeding 1.0 mg daily in divided dosages. Problems with cardiac arrhythmia or dystonia were not encountered. Newer, atypical antipsychotics were not used during the period of this study.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies of delirium in children and adolescents have been limited. The last clinical study of delirium in children and adolescents was published in 19805 and compared a group of 33 children and young adolescents with acute central nervous system (CNS) disorders of toxic, metabolic, traumatic, and other etiologies to 19 other hospitalized children who had no apparent CNS disorder.5 The children in the study were 6 to 17 years old (mean 12 years). Memory, orientation, electroencephalogram, and neuropsychologic function were abnormal in patients with delirium compared to controls, and some patients had persistent perceptual-motor deficits for several weeks after recovery. Reassurance and reorientation were considered more effective therapy than sedative medication.5 Although not specifically studies of delirium, symptoms of delirium have been described in seriously ill patients in the pediatric intensive care unit (ICU)8 and in children following severe burns, in whom haloperidol was found to be effective in reducing agitation, restlessness, disorientation, hallucinations, delusions, and insomnia.9

The clinical presentation of delirium in this study of children and adolescents was similar to that considered characteristic of the disorder in older patients. The core symptoms of delirium are reflected in the current standardized criteria for diagnosis, and include acute onset and fluctuating course, inattention, disorientation, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness.10 These DSM-IIIR and DSM-IV criteria were based on field testing in adults.1 Associated symptoms of hallucinations, misperceptions, illusions, and delusions are seen in about 40% of adults with delirium.10 A similar pattern of symptoms, including disturbed attention, disorganized behavior, sleep disturbance, altered level of consciousness, and occasionally hallucinations was noted in patients in this study. Mortality is higher in adults with delirium compared to nondelirious patients,11 and mortality was similarly high in the delirious patients in this study.

Delirium may result from many different causes, including infection, drugs and toxins, metabolic dysfunction, and other serious illness, and delirium is fundamentally treated by addressing the underlying illness or condition that caused it.12 Psychopharmacologic treatment is formulated to address the alterations in neurotransmitters that have been documented in delirium. Changes are noted in levels of acetylcholine, gamma amino-butyric acid, dopamine, glutamine, serotonin, and histamine.10 Anticholinergic agents, including antihistamines and opioids, further reduce levels of acetyl choline, produce impairment in memory and attention, and thus may exacerbate or result in delirium.13 Benzodiazepines increase already elevated levels of GABA, which adds to confusion and memory impairment and may increase agitation.14 Antipsychotic dopamine antagonists are the recommended pharmacologic treatment for delirium.12 This relative excess of dopamine may be related to the characteristic symptoms of delirium, and antipsychotic medications can provide symptomatic benefit for patients with delirium.10 Antipsychotic drugs were found to be helpful in controlling symptoms of delirium in the pediatric patients in this study.

An understanding of delirium is fundamental to the field of consultation-liaison psychiatry, and psychiatrists consulting to pediatricians need to be familiar with the clinical symptoms and treatment of delirium in children and adolescents and recognize the risk it represents. This study has demonstrated that the presentation, symptoms, and course of delirium are similar across the life cycle and confirmed that the DSM-IV criteria are clinically relevant and applicable to the pediatric population, and it sets the stage for further studies of delirium in the young.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Presented at the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Toronto, Ontario, October, 1998

|

|

|

1 Liptzin B, Levkoff SE: Analysis of data on a large geriatric hospitalized population relevant to the DSM-IV criteria for delirium. APA DSM-IV Sourcebook. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994, pp 87–90Google Scholar

2 Trzepacz PT: A review of delirium assessment instruments. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1994; 16:397–405Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition revised, (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2000Google Scholar

4 Trzecapz PT: Delirium: advances in diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment. Psychiat Clin N Am 1996; 19:429–448Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Prugh DC, Wagonfield S, Metcalf D, et al: A clinical study of delirium in children and adolescents. Psychosomatic Med 1980; 42suppl:177–195Google Scholar

6 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition, revised (DSM-IIIR). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1989Google Scholar

7 Othmer E, Othmer SC. The Clinical Interview Using DSM-IIIR. American Psychiatric Press Inc, 1989; pp 465–466Google Scholar

8 Jones SH, Fiser DH, Livingston RL: Behavioral changes in the pediatric intensive care units. Am J Dis Child 1992; 146:375–379Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Brown RL, Henke A, Greenhalgh DG, et al: The use of haloperidol in the agitated, critically ill pediatric patient with burns. J Burn Care Rehabil 1996; 17:34–38Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Trzepacz PT: Update on the neuropathogenesis of delirium. Dementia & Geriatric Cognitive Disorders 1999; 10:333–334Crossref, Google Scholar

11 van Hemert AM, van der Mast RC, Hengeveld MW: Excess mortality in general hospital patients with delirium: a 5-year follow-up of 519 patients seen in psychiatric consultation. J Psychosomatic Res 1994; 38:339–346Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Trzepacz PT, Breitbart W, Franklin J, et al: Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with delirium. Am J Psychiatr 1999; 156suppl:1–20Google Scholar

13 Tune L, Carr S, Hoag E, et al: Anticholinergic effects of drugs commonly prescribed for the elderly: potential means for assessing risk of delirium. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1393–1394Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Breitbart W, Marotta R, Platt MM, et al: A double-blind trial of haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and lorazepam in the treatment of delirium in hospitalized AIDS patients. Am J Psychiatr 1996; 153:231–237Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar