Psychopathology in Neuropsychiatry: DSM and Beyond

Abstract

The case reports described in this article indicate that current neuropsychiatric practice is strongly limited by reliance on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Knowledge of new psychopathology that will enable the neuropsychiatrists and neuroscientists identify specific areas of brain dysfunction is essential to modern practice of neuropsychiatry. Today, less than 20% of neuropsychiatry and neuroscience programs teach such psychopathology.The development of brain imaging and metabolic measurement technologies; the continuous and rapid introduction of many new pharmaceutical agents into clinical care; and the various, detailed editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) have all shaped modern psychiatric training and thus future psychiatric practice. This “shaping” is observed most often in the teaching of psychopathology and of mental status examinations, both currently focusing on how to recognize and elicit the clinical features needed to apply the criteria set by the DSM. Once DSM criteria are met, a best-choice treatment plan based on DSM diagnosis is selected from an array of pharmacotherapy algorithms. It is assumed that the known reliability of the DSM system maximizes the likelihood that these diagnostic decisions are valid and treatment choices are therefore appropriate. Descriptive psychopathology that goes beyond the DSM is primarily relegated to historical consideration and rarely pertains to issues regarding patient care.

Reliance on the DSM for all psychopathology needed to diagnose patients is worrisome because of the concern regarding several aspects of the manual. For example, some DSM categories, such as dissociative disorders, lack consensus,6 while others, such as borderline personality disorder, imply homogeneity where none exists.1,9 The high proportion of patients that receive the DSM not otherwise specified (NOS) choice also attests its limitations.11

The practice of neuropsychiatry often requires that assessments extend beyond traditional psychiatric assessment and integrate concepts of brain driving the behavior. It also requires familiarity with several neurological phenomena not incorporated in the DSM checklist. For example, recognizing psychosensory features in a patient with panic disorder may alert a clinician toward a diagnosis of seizure. The presence of Capgras phenomenon in a depressed patient may, likewise, raise the possibility of a parietal lobe stroke.

There is, however, anecdotal and clinicopathological evidence of the utility of assessing a patient’s psychopathology beyond what is necessary to apply DSM criteria. Hirschfeld3 reviews the behaviors consistent with a bipolar spectrum, a construct not implicitly incorporated in the DSM, but one that might lead to more specific treatments for many patients currently being diagnosed as having personality disorders. Cyclothymia, a personality disorder in the DSM-II, is presently categorized as a mood disorder in the DSM-IV. Kaptsan et al.5 describe the differential diagnosis merits of the oneiroid syndrome, which is well known to European psychiatrists but often overlooked in the U.S. Joseph4 summarizes behaviors that are associated with frontal lobe disease, commonly observed in psychiatric patients, but not included in the DSM as inclusion or exclusion criteria or subtyping. Pelegrin et al.8 and Onuma7 review the diagnostic usefulness of psychopathology associated with traumatic brain injury (TBI) and epilepsy, respectively.

Case 1

A 78-year-old woman being treated with bupropion for a late occurring depression was brought to an emergency room because of confusion followed by mutism and immobility. Admitted to a neurology service, her magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was read as showing some old ischemic disease, but without evidence to explain her present state. The mutism and immobility resolved within an hour of admission. Over the next several hours the patient’s state fluctuated with periods of disorganized, fluent speech followed by apparent alertness associated with reduced affective intensity, mild sadness, feelings of low energy, and psychomotor retardation. When lucid, she said she had no future. Prior to hospitalization she had been eating and sleeping poorly. Because her alternating periods of confusion and alertness were believed related to the presence of her daughter in her room, and because her catatonic features resolved so quickly, she was diagnosed as being depressed with conversion features, and transferred to the psychiatry inpatient unit. She met DSM criteria for major depression.

A psychiatry consultant saw the patient and noted that she was subdued and appeared tired, but that she retained some humor, inconsistent with the degree of her depressive features. (The DSM does not consider patterns of features, but rather the number of features). The consultant also noted that the patient’s periods of confusion began abruptly and were characterized by a poor auditory comprehension resulting in nonsequitive responses. (The DSM does not define speech and language disorders in specifics as do neurology criteria sets, and it considers episode duration, but not duration or fluctuations of individual features.)

Because psychopathology from idiopathic disorders does not typically begin in seconds, aphasia from vascular disease does not come and go abruptly, and transient catatonia unrelated to a bipolar disorder is often due to coarse brain disease, the consultant concluded that the patient was in nonconvulsive status. This was confirmed by electroencephalogram (EEG), and IV anticonvulsants resolved the patient’s acute state.

The DSM typically lists clinical features and requires a patient to have a certain number to meet criteria. The combination of features, their characteristic onset, the relationships among different patterns, the context in which symptoms unfold is rarely addressed. Although the duration of a syndrome in days, weeks or months is a typical requirement to aid reliability, the more difficult assessment of the quality of symptom onsets, the sequence of symptom appearances, and patterns is not incorporated. Thus, although the above patient meet DSM criteria for major depression, there was no way for a DSM view of psychopathology to recognize that the intensity of mood was inconsistent with the intensity of other depressive features, or that split-second changes in psychopathology usually indicates a secondary syndrome.

Case 2

A 28-year-old man had been experiencing auditory hallucinations (voices commenting and conversing) daily for years. The hallucinations were perceived as originating from some source external to the patient. They were loud and clear and derogatory in content. They were most intense for several hours in the morning, but he would hear them occasionally in the early afternoon. He recognized that his experiences were a sign of illness, but when the voices were most intense, he believed them to be real and not self-generated. He did not work, had no future plans, and mostly kept to himself, worrying about the voices and fearful of their inevitable return. His emotional statement was not reduced and his moods were appropriate. He had no speech or language disorder. He was occasionally suspicious of strangers, sometimes assuming they might be the source of the voices. He had never been depressed or manic. Diagnosed as schizophrenic and meeting DSM criteria, he had been on several antipsychotics, but with minimal relief.

A consultant noted that the patient’s hallucinations typically began while still in bed. The patient would awaken and become immediately frightened and then the voices would begin. After several hours, they would diminish in intensity and then end. In the afternoons, they occurred after lunch. Because a non-affective psychosis with preserved emotional statement is often associated with coarse brain disease,2 and hallucinations that are linked to a specific time of day, event, or stimulus are also most likely due to coarse brain disease, the consultant suggested the hallucinations were post-ictal following seizures that occurred upon wakening (when the afternoon voices occurred it was after a heavy lunch followed by a nap). Carbamazepine dramatically improved this man’s psychosis.

Again, the DSM does not incorporate such nuances into criteria, despite many descriptions of the psychopathology associated with epilepsy,10 and the high frequencies with which epileptics have associated depression, psychosis, and personality change, and as a result come regularly to psychiatric clinics and hospitals for care.

Although the framers of the DSM might maintain that the manual is not intended as a textbook of psychopathology, the manual may have become just that to the exclusion of works devoted to a fuller understanding of psychopathology. To begin to address this, we surveyed residency directors of U.S. accredited programs in psychiatry to determine the extent to which descriptive psychopathology is taught beyond the DSM.

METHOD

After IRB approval at our institution, we surveyed by mailing all accredited psychiatry residency training programs in the U.S. listed in the American Association of Directors of Psychiatry Residency Training (AADPRT). The survey covered the number of courses and classroom hours devoted to teaching psychopathology, the use of classic textbooks about psychopathology, and the classic areas of psychopathology that are covered in each residency. After the initial mailing, a second mailing was sent six weeks later.

RESULTS

Of the total 149 surveys sent, 68 (45.6%) responded. Program characteristics: Only one program from mountain states responded, the rest of the surveys were equally distributed among US regions. forty (58.8%) of the respondents were from public universities, 17 (25%) were from private universities, 8 (11.8%) were freestanding, 2 (2.9%) were in combination settings, 3 (4.4%) were exclusively in the outpatient setting, 1 was in a hospital setting, 1 (1%) was in the community, 62 (91.2%) were set in combinations settings, 57 (83.9%) of programs identified their theoretical backgrounds as eclectic. Only 3 (4.4%) identified the background as psychodynamic where as 2 (2.9%) were neuropsychiatric, and 2 (2.9%) were psychopharmacologic. This distribution is consistent with national distribution.

Teaching of DSM, Mental Status and Psychopathology

Thirty-two (47.1%) programs did not offer a formal course in the use of DSM. Most of those who offered it in the first and second years and devoted less than five hours. Fifty-three (77.9%) programs offered a course in descriptive psychopathology primarily in the PGY-1 and 2 years, and most frequently 11-30 hours were devoted to the psychopathology. Fifty-three (77.9%) programs also offered a course in mental status examination primarily in the first year and mostly less than 5 hours were devoted to this course.

These findings suggest that at least 20% of the program have no formal courses in descriptive psychopathology or mental status examination and about 50% do not teach any course in the use of DSM at all.

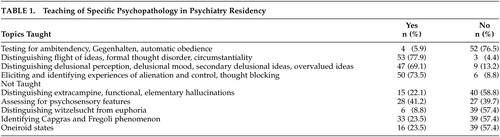

Teaching of Specific Psychopathology

Specific topics covered in psychiatry residencies are listed in Table 1. It is apparent that less than 30% taught how to recognize various catatonic signs, extracampine or elementary hallucinations, oneiroid states, recognizing Capgras or Fregoli syndrome, Witzelsucht.

Use of Classic Texts

Less than 20% used Bleuler's Dementia Praecox (17.6%) or Kraepelin's Manic Depressive Illness (19.1%) or Schneider's Clinical Psychopathology (17.6%), four programs (5.9%) endorsed using Jasper's Psychopathology. One program each used Kahlbaum's Catatonia and Fish's Schizophrenia.

DISCUSSION

Although this survey is limited by a low response rate, this response is, nevertheless, consistent with such surveys. These findings suggest that a core of our residency program do not emphasize psychopathology in their curriculum. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders which is frequently quoted is not being taught systematically in the majority of programs. Should this be of concern to a psychiatrist and then neuropsychiatrist? May be newer psychopharmacologic agents have reduced the need for assessing psychopathology. What difference does it make if one drug cures all psychotic symptoms or depressive symptoms anyway? Further, DSM requires only a few criteria be met. Does this limited reliance on psychopathology interfere with our diagnostic ability and treatment plan?

If neuropsychiatric disorders need to be identified and treated appropriately, it is imperative that our residency programs focus on psychopathology. Identification and knowledge of psychopathology beyond DSM is a prerequisite for expanding resident's understanding of neuropsychiatry.

|

1 Andrulonis PA, Glueck BC, Stroebel CF, et al: Borderline personality subcategories. J Nerv Ment Dis 1982; 170:670–679Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Davison K, Bagley CR: Schizophrenia-like psychoses associated with organic disorders of the central nervous system: a review of the literature. Br J Psychiatry 1969; Spec Pub No. 4:113–184Google Scholar

3 Hirschfield RM: Bipolar spectrum disorder: improving recognition and diagnosis. J Clin Psychiatry2001; 62 suppl 14:5–9Google Scholar

4 Joseph R: Frontal lobe psychopathology: mania, depression, confabulation, catatonia, perseveration, obsessive compulsions and schizophrenia. Psychiatry 1999; 62:138–172Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Kaptsan A, Meodownick C, Lerner V: Oneiroid syndrome: a concept of use for which western psychiatry. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 2000; 37:278–285Medline, Google Scholar

6 Lalonde JK, Hudson JI, Gigante RA, et al: Canadian and American psychiatrists' attitudes toward dissociative disorders diagnosis. Can J Psychiat2001; 46:407–412Google Scholar

7 Onuma T: Classification of psychiatric symptoms in patients with epilepsy. Epilespia 2000; 41 suppl 9:43–48Google Scholar

8 Pelegrin VC, Gomez Hernandez R, Munoz Cespedes JM, et al: Nosologic aspects of personality change due to head trauma. Rev Neurol2001; 32:681–687Google Scholar

9 Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, McGlashan TH: Factor analysis of the DSM-III-R borderline personality disorder criteria in psychiatric inpatients. Am J Psychiatry2000; 157:1629–1633Google Scholar

10 Taylor MA: The Fundamentals of Clinical NeuropsychiatryOxford University Press, New York, 1999Google Scholar

11 Wilson WH: Reassessment of state hospital patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1989; 1:394–397Link, Google Scholar