The Size of Demand for Specialized Neuropsychiatry Services: Rates of Referrals to Neuropsychiatric Services in the South Thames Region of the United Kingdom

Abstract

The authors assessed the number of referrals to neuropsychiatry services covering South London, Kent, Surrey, and Sussex (population 6,887,000) over a 2-year period. The average referral rate was 11.2 per 100,000 per population for each year. Geographical distance from the specialist provider strongly affected referral rates, with clinicians in South London making more referrals than those from outside London. Assessment of appropriateness of referrals indicated that more than 86% of referrals were highly appropriate, and thus the higher level of referrals from close proximity cannot be attributed to inappropriate referrals. A survey of clinicians reported lower awareness of services and how to access these services among those clinicians working at a greater distance from the service provider, which likely results in unmet needs. Greater attempts should be made to improve access to neuropsychiatric services for clinicians who do not practice within close proximity of a specialist neuropsychiatry service.

Neuropsychiatry is considered the interface between neurology and psychiatry,1 and a steady growth in clinical and academic interest in this field has been observed in recent years. Many neurological disorders have high rates of neurobehavioural problems, including psychiatric illness. Incidence statistics describe the number of new cases that present with a condition within a particular time period, and these statistics can provide some indication of the likely number of referrals to a service. It can be conservatively estimated that four new cases of depressed individuals with Parkinson’s disease are identified per 100,000 per population each year.2,3 Deb et al.,4,5who investigated rates of psychiatric disorders among individuals with a brain injury, estimated that approximately 36 individuals per 100,000 per year sustain a head injury and are diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder. Approximately four individuals with epilepsy are identified with postictal psychiatric events per 100,000 population annually.6,7 These statistics indicate that at least 30 to 50 individuals per 100,000 among the adult population each year are likely to develop significant psychiatric symptoms related to a neurological disorder.

In 1999, the National Service Framework for Mental Health: Modern Standards and Service Models was outlined by the Department of Health, United Kingdom (UK)8 to identify the priorities within the mental health service in the National Health Service (NHS) UK. It recommended that to provide a comprehensive mental health service there needed to be clear guidance on how and when to refer patients to specialized services. The Department of Health has identified neuropsychiatry as a specialized mental health service.9 This is because the needs of those with psychiatric disorders of organic etiology are typically complex and multifaceted. However, it recognizes that there are still “information problems” (p. 1) with the definitions of specialized services. It is important to identify whether individuals in need of specialized neuropsychiatric services are receiving the treatment they require and to have some estimate of how much neuropsychiatry is needed in order to plan.

South London & Maudsley NHS Trust (which includes The Maudsley Hospital and the specialized neuropsychiatry service based at St. Thomas’ hospital) and South West London & St. George’s Mental Health Trust provide specialized neuropsychiatric services from three hospital sites in South London for patients from the 6,887,000 population of South London, Kent, Surrey and Sussex. These neuropsychiatry services take a few additional referrals from further afield, but these were not the subject of this study. Within the geographical area of South London, Kent, Surrey and Sussex there are no other neuropsychiatry service providers, and only occasional referrals are made to neuropsychiatry services outside of the area. Referrals are accepted from a wide range of professionals and agencies, including psychiatric services, clinical neuroscience centers, general hospitals and general practitioners (GPs). The service is provided primarily on an outpatient basis, although there are 20 neuropsychiatry inpatient beds at South London & Maudsley NHS Trust.

Consensus opinion prior to the study suggested that there is marked variation in referral rates across South London, Kent, Surrey and Sussex to specialized neuropsychiatric services. If there were marked differences in referral rates across the region, was it because of inappropriate referrals to neuropsychiatric services from those with high rates of referrals, or because there is unmet need in those areas with low referral rates (assuming the true demand is consistent across geographical regions).

To elucidate these issues, the key objectives of this study were to determine referral rates, appropriateness of referrals, and clinician awareness and satisfaction as outlined below:

Referral Rates

| 1. | The number of neuropsychiatry referrals currently being received by a specialist service covering a defined region; and | ||||

| 2. | Whether there are variations in numbers of referrals made to the neuropsychiatric services, depending on geographical area of the patient’s residence. | ||||

Appropriateness of Referrals

| 1. | Whether a significant proportion of referrals were found to be inappropriate (i.e., not requiring a specialist neuropsychiatric service). | ||||

We needed to establish criteria of appropriateness since there is no consensus regarding these standards. Variations in referral patterns, if the majority were appropriate, would suggest poor equity of access to neuropsychiatric services.

Clinician Awareness and Satisfaction

| 1. | Whether clinicians are aware of and satisfied with specialist neuropsychiatry services and what barriers they feel exist regarding access; and | ||||

| 2. | Is there consensus agreement among clinicians as to when a referral to neuropsychiatry services is appropriate? | ||||

METHODS

Referral Rates

The rates of referrals from South London, Kent, Surrey and Sussex to neuropsychiatric services was determined in a retrospective audit from the hospital databases of the Maudsley Hospital (April 1999-March 2001) and St Thomas’ Hospital (October 2000-March 2001). Data were collected prospectively over a period of 6 months from the database of the South West London & St George’s Mental Health Trust (January 2002-June 2002). Data were collapsed across the three sites.

Appropriateness of Referrals

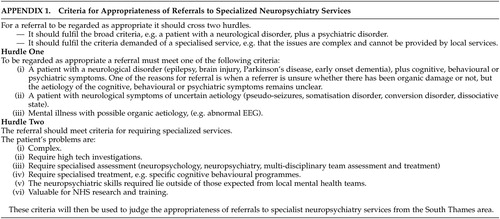

A prospective audit of referrals to neuropsychiatry services was undertaken at the Maudsley Hospital (October 2001-March 2002), St Thomas’ Hospital (January 2002-June 2002) and South West London & St George’s Mental Health Trust (January 2002-June 2002) using a structured analysis of appropriateness. The three neuropsychiatry services were contacted in order to obtain their operational policies describing the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the service. The criteria used in the current study were developed from these, in light of Regional Specialized Commissioning guidance. These appropriateness criteria were then circulated among neuropsychiatrists working at the three centers for comment and amended accordingly. The resultant criteria of appropriateness are as follows:

| 1. | That a patient should: a) suffer with a neurological disorder and have cognitive, behavioral or psychiatric symptoms; b) have medically unexplained neurological symptoms; or c) have a mental illness with a possible organic etiology. If this first hurdle was passed, the referral was rated on the six criteria listed below for determining Regional Specialized Commissioning of NHS services: | ||||

| 2. | The patient’s problems are: a) complex; b) require specialist investigations; c); require specialist assessment; d) require specialist treatment; e) the neuropsychiatric skills required lie outside those expected in local mental health services; and f) there is value in the referral in terms of facilitating NHS research and development. | ||||

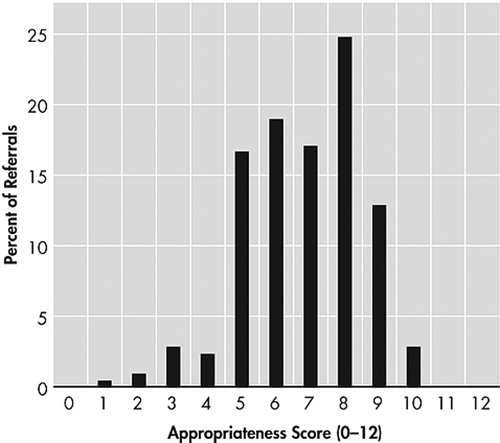

These six items were each scored 0 (unlikely), 1 (quite likely) or 2 (more than probable). Therefore the total appropriateness scores ranged from 0–12.

A small pilot study was conducted to assess whether the criteria could be reliably applied. An independent assessor evaluated 23 new referral letters according to the standards and criteria for referral. The referral letters were then reassessed by a neuropsychiatrist to determine interrater reliability. The data were reclassified as appropriate (arbitrarily defined as a score of 5 or above) or inappropriate, and a Cohen’s kappa was performed. This yielded a kappa value of 0.56, indicating moderate agreement9 between the raters.

Clinician Awareness and Satisfaction

To complement the study of referral rates and appropriateness, we distributed questionnaires to 508 clinicians (200 GPs and 308 psychiatrists, neurologists, neurosurgeons and psychologists) throughout the area to determine their views on the accessibility and value of specialist neuropsychiatric services. The sample of clinicians was selected to be a representative sample of all clinicians across the geographical areas of interest. Individuals were sampled from a database compiled from the Department of Health General Practitioners list, The Medical Directory for neurologists and psychiatrists, membership lists of the British Psychological Society-Division of Neuropsychology and The British Neuropsychology Society, and direct telephone calls were made to mental health trusts to confirm the names. The questionnaire aimed to assess both awareness of and satisfaction with the services provided. Clinicians were also asked to determine any barriers they felt existed to access.

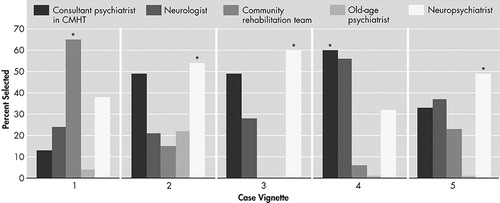

Additionally, we wanted to find whether clinicians agreed with our judgment as to when a referral to neuropsychiatry services was appropriate. The questionnaire included five case vignettes (CV; see Appendix II) and clinicians were asked to identify the specific service that would best meet the needs of the patient from a choice of: consultant psychiatrist in Community Mental Health Team [CMHT], neurologist, community neurorehabilitation team (whose remit must include a service for patients with acquired neurological disorders),10 old-age psychiatrist, and neuropsychiatrist. The vignettes were designed by a panel of neuropsychiatrists to illustrate two cases that were inappropriate for neuropsychiatry (vignette 1 [Community Neurorehabilitation Team] and vignette 4 [Consultant Psychiatrist in Community Mental Health Team]) and three vignettes that were appropriate for neuropsychiatry.

RESULTS

Referral Rates

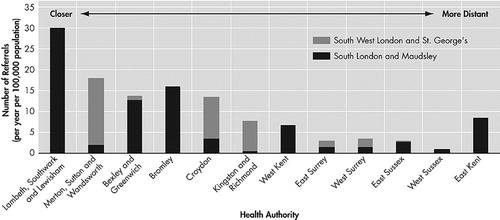

Over the 2 years there was a total of 1152 referrals from South London & Maudsley NHS Trust, and over 6 months 97 referrals to South West London & St. George’s Mental Health Trust. These figures have been adjusted to give rates per 100 000 population per year. The average rate of referral was 11.2 per 100,000 population per year. Figure 1 shows the variation in referral rates across the geographical regions investigated, and referrals to the two trusts are shown separately. Referral rates were as high as 30.8 per 100 000 per year from Lambeth, Southwark and Lewisham where 2 of the 3 neuropsychiatry services are based, and as low as 0.9 per 100,000 per year from West Sussex (about 60 miles from South London). There was a clear relationship in terms of geographical distance from the specialist provider with relatively high rates of referral from health districts within South London and steadily lower rates of referrals from health districts in Kent, Surrey and Sussex with increasing distance from London. East Kent was an exception to this rule having moderate rates of referral.

South West London & St. George’s received fewer referrals in total than South London & Maudsley NHS Trust. The large majority of the referrals to South West London & St. George’s were from three health districts: Merton, Sutton & Wandsworth; Croydon; and Kingston & Richmond.

Appropriateness of Referrals

The second aim of the study was to assess the appropriateness of the referrals. In total in the prospective audit undertaken over 6 months, 227 referrals were made to the South London & Maudsley NHS Trust and South West London & St. George’s Mental Health Trust. Only 17 (7.5%) of these did not pass the first hurdle, i.e., were inappropriate and this was either a result of too little detail on the referral form to assign a score (N = 11), or because the patient should have been referred to old-age psychiatry (N=3) or were not neuropsychiatric referrals (N=3).

It was found that the majority of all referrals (86%) were highly appropriate (scoring at least 5/10 on the appropriateness score). The distribution of appropriateness scores can be seen in Figure 2.

Clinician Awareness and Satisfaction

There was a response rate of 18% (93 of the 508 questionnaires returned). 24% of psychiatrists (including psychotherapists) contacted responded and 19% of psychologists. The response rate for GP’s and neurosurgeons was much lower, at 13% and 9% respectively. There was a wide geographic distribution of respondents. The highest number of respondents in the sample were clinicians from South West London (37 of the 93 respondents, 40%), followed by South East London (21 out of 93, 23%), and Kent (16, 17%). Surrey had the lowest number of respondents (7, 7%), followed by Sussex (12, 13%).

A greater proportion of respondents in the London area were aware of the availability of specialist neuropsychiatric services. This was as high as 90% of clinicians in South East London. The largest proportion that said they were not available was from Surrey (43%) followed by Kent (38%), while the majority of respondents (58%) from Sussex had no idea about availability.

Of the respondents 39% were satisfied or very satisfied with specialist neuropsychiatric services, whereas 14% were not; the remaining 47% did not use these services or did not state a preference. Respondents tended to be less satisfied with local general psychiatrists providing neuropsychiatric services (17% were satisfied or very satisfied, and 12% were not satisfied).

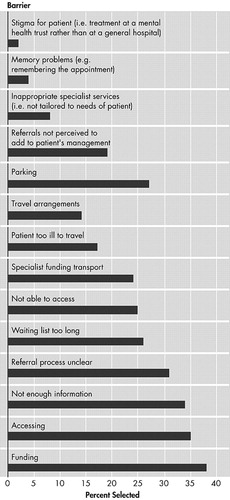

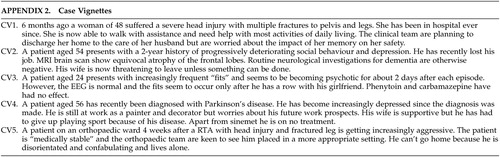

The majority of clinicians (62%) did not perceive any barriers to referrals to specialist neuropsychiatric services. Organizational issues e.g., long waiting list or difficulties with funding arrangements were perceived as a greater hindrance to referral to neuropsychiatric services than were potential difficulties for the patient accessing the service (e.g., travel arrangements) (Figure 3).

A small proportion of patients may be being referred to neuropsychiatry service other than St George’s, St Thomas’ and the Maudsley—but feed back from clinicians did not identify alternative sites as being a significant provider of neuropsychiatry.

There were 82 responses relating to the five case vignettes given to assess the level of consensus among clinicians in referring patients (from the 93 clinicians who responded to the questionnaire sent to a total of 508 clinicians). Although there was a wide range of opinion, the majority preference was in agreement with the judgment of the neuropsychiatrists (Figure 4). So, for example, for vignette 1 which was regarded as more appropriate for a community neurorehabilitation team than neuropsychiatry, the community neurorehabilitation team was endorsed by 65% of respondents with only 38% regarding neuropsychiatry as appropriate. Because respondents were allowed to endorse more than one appropriate service per vignette the sum total of percentage endorsements across the 5 possible services is greater than 100%.

DISCUSSION

Overall, there is a clear lack of equity of access to neuropsychiatry services for patients living in South London, Kent, Surrey and Sussex, with clinicians in South East and South West London making more referrals than those from outside London. It seems likely that this is because clinicians at a distance from South London are less aware of neuropsychiatry services and how to access them, and that this results in unmet need. There is no evidence of inappropriate referrals from clinicians in regions with higher rates of referrals; appropriateness scores were high across all regions and clinicians were generally aware when a patient required specialist neuropsychiatric services. However, the appropriateness criteria were not systematically tested in advance, although they were based on Regional Specialized Guidance and evaluated by a group of neuropsychiatrists. The conclusion that the differing referral rates across the region is due to varying awareness of neuropsychiatry services is supported by the finding that there was an increase in number of referrals in West Kent after the establishment of a specialist neuropsychiatry clinic in the area in 1996, which continues to operate.11 The relatively high level of referrals from East Kent is unexplained but may reflect the presence in East Kent of a neurologist with a special interest in epilepsy.11

In general, 11.2 referrals to neuropsychiatry services per 100,000 population per year were received. Referral rates of 30 per 100,000 population per year from Lambeth, Southwark and Lewisham may reflect the optimal rate. However this district has one of the highest expenditures per capita on mental health in the U.K. and is served by mental health services within the South London and Maudsley NHS Trust. Both these factors could cause an unrealistically high estimate of need. On examination of all referral rates, it was felt that 15 to 20 per 100,000 population per year was a more realistic target to set as indicative of the size of the demand. In areas where the referral rate is less than 15 per 100 000 per year it is likely that there is unmet need in terms of access to specialist neuropsychiatric referrals.

The service delivery questionnaire indicated that satisfaction with the specialist services was generally good, although those who employed the neuropsychiatric services from local general psychiatrists were less likely to report satisfaction. Those barriers to accessing the specialist services that were endorsed were primarily organizational issues. Using case vignettes there was reasonable agreement as to which cases required neuropsychiatry and which did not. The range in opinion may reflect different routes taken by clinicians in different areas to access help; perhaps increasing the likelihood that the different referral rates across the region are due to issues related to equity of access rather than different clinical judgements regarding what is appropriate. However, it may of course reflect a genuine lack of consensus among clinicians as to which cases do require neuropsychiatry.

The key aim of this audit of neuropsychiatric referrals is to improve patient care. In order to do this it is important to consider the clinical implications of the findings to outline a strategy for change.

A paucity of referrals was identified at a distance from the centers providing specialist neuropsychiatry. To redress this imbalance, clinicians, particularly those at a distance, need better information regarding access to services and which patients might be appropriate to refer to the service. Protocols should be established for referring to the service in line with the recommendations of the Department of Health.8 Neuropsychiatry services should consider increasing the number of outreach services available locally. This has been shown to be effective as evidenced by the high rates of referral in West Kent compared to neighboring counties subsequent to the development of an Outreach Clinic in the area. A reasonable target for all areas was considered to be 15–20 referrals per 100,000 per year.

While there was general agreement regarding where to refer specific patients in the case vignettes, and the majority of clinicians selected the correct preference for referral, most also suggested more than one clinical referral, indicating that there is often more than one route to accessing help. In addition these may vary across different areas. This finding indicates that further clinical education is necessary in order to inform clinicians as to which types of patients need referral, when and to whom. It also signifies that although clinicians are making appropriate referrals, there is a lack of awareness of or means of accessing specialist services.

Where barriers to referrals to specialist neuropsychiatric services were identified it was the organizational barriers to the service, which they viewed as more impeding than the particular difficulties in accessing the service such as travel arrangements. However, we have not surveyed patients’ views. They may perceive different barriers to accessing the neuropsychiatric services.

The findings of this audit may not be surprising, but it is important to know the potential magnitude of inequity of access to neuropsychiatric services in order to redress the imbalance. Although this study was based in South East England, we believe that it is likely to be of general interest, despite wide variations in the presence of neuropsychiatry services and their accessibility across regions and countries. To make our findings as generalizable as possible, we have provided what we believe is a conservative estimate of the appropriate referral rate for specialist neuropsychiatry services.

CONCLUSIONS

Referrals to three specialist neuropsychiatric services were evaluated in order to explore equity of access, appropriateness of referrals, and satisfaction with these services reported by the referring clinicians. It was found that there was a clear inequity of access, with areas outside London showing much lower rates of referrals to the units involved. However, this was found not to be a result of inappropriate referrals but the result of poor awareness of how to access the specialist services. It is likely that patients in areas with less than 15 referrals per 100,000 annually to neuropsychiatry services are not receiving adequate access to such services.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was presented at a meeting of the Special Interest Group in Neuropsychiatry of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, U.K., September 24, 2004.

The authors thank Professors Tony David and Michael Kopelman, and Drs. Brian Toone, John Mellers, and Ben Wright.

FIGURE 1. Histogram Showing Geographic Spread of 1,152 Referrals to the Maudsley Hospital, St. Thomas’ Hospital, and South West London & St. George’s Mental Health Trust (from 1999 to 2001)

FIGURE 2. Histogram Showing Appropriateness Scores of Referrals

FIGURE 3. Histogram Showing Percentage of Respondents That Selected Each Item as a Perceived Barrier Affecting Their Decision to Refer to Specialist Services

FIGURE 4. Histogram Showing Percentage of Respondents That Selected Each Service to Refer the Patient (as described in the case vignettes)

|

|

1 Lishman WA: Organic Psychiatry: Psychological Consequences of Cerebral Disorder, 3rd ed. Oxford, Blackwell Scientific Science, 2001Google Scholar

2 Dooneief G, Mirabello E, Bell K, et al: An estimate of the incidence of depression in idiopathic parkinson’s disease. Arch Neurol 1992; 49:305–307Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Twelves D, Perkins KS, Counsell, C: Systematic review of incidence studies of parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 2003; 18:19–31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Deb S, Lyons I, Koutzoukis C, et al: Rate of psychiatric illness 1 year after traumatic brain injury. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:374–378Medline, Google Scholar

5 Deb S: ICD-10 codes detect only a proportion of all head injury admissions. Brain Inj 1999; 13:369–373Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Office of Health Communications and Public Relations: Epilepsy: Aetiology, Epidemiology and Prognosis. Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2001Google Scholar

7 Kanner AM, Stagno S, Kotagal P, et al: Postictal psychiatric events during prolonged video-electroencephalographic monitoring studies. Arch Neurol 1996; 53:S53-S67Google Scholar

8 Department of Health: The National Service Framework for Mental Health: Modern standards and service models. London: Department of Health, 1999Google Scholar

9 Landis JR, Koch GG: The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33:159–174Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 McMillan TM, Ledder H: A survey of services provided by community neurorehabilitation teams in south east england. Clin Rehabil 2001; 15:582–588Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Leonard F, Majid S, Sivakumar K, et al: Service innovations: a neuropsychiatry outreach clinic. Psych Bull 2002; 26:99–101Crossref, Google Scholar