Impaired Perception of Affective Prosody in Schizophrenia

Abstract

The authors aimed to explore schizophrenia patients’ ability to perceive affective prosody. Specifically, certain emotions that may be more troublesome for patients and possible gender differences in prosody perception were assessed. Thirty six schizophrenia patients and 32 age-, education-, and gender-matched healthy comparison subjects assessed on an affective prosody test were examined. Patients were impaired on recognition of affective prosody overall, and their difficulties with prosody perception may be attributed to those emotions with negative valence, specifically anger and sadness. Findings revealed that only male patients were impaired on prosody perception. Deficits in the perception of affective prosody were principally evident in emotions with negative valence and male patients with schizophrenia. Future studies should explore the influence of these deficits on social and interpersonal functioning more directly.

Social cognition includes processes such as “theory of mind” skills, affect recognition, social cue perception, and attributional style.1 Whether social cognition is relatively independent from other aspects of cognition1 or it expresses the operation of neurocognitive abilities within social and interpersonal situations,2 it has been linked to social behavior.1 Impairment in social functioning (e.g., the ability to work, maintain interpersonal relationships, and care for oneself) is a hallmark characteristic of schizophrenia.3 Consequently, various facets of social cognition in patients with schizophrenia have received growing attention in recent years (for a review of affect perception studies in schizophrenia see Mandal et al.4 and Edwards et al.5 and for a review of “theory of mind” studies in schizophrenia see Brüne).6

Affect perception refers to the ability to accurately perceive, interpret and process emotional expressions in others.7 Prosody is a nonlexical component of speech and is divided into stress prosody, which entails decisions about semantic meaning and affective prosody, which communicates information about the emotional state of others. Perception of affective prosody refers to the recognition of emotion from prosodic intonation.5

In contrast to the volume of research on facial affect recognition in schizophrenia, the literature on the perception of affective prosody remains quite sparse.5 Nevertheless, several studies have reported deficits in the perception of affective prosody in schizophrenia. Patients with schizophrenia were impaired on affective prosody recognition relative to healthy individuals8–13 and patients with affective psychoses,11 but they were equally impaired as patients with other psychotic disorders11 and right brain damage.12 These findings are relevant to first episode schizophrenia,11 as well as both unmedicated8 and medicated9,10,12,13 patients who have had schizophrenia for a number of years. In these studies, patients presented a specific deficit in the recognition of negative emotions.11,14 In contrast, one study of affective prosody in schizophrenia failed to find a deficit.15 Performance on affective prosody recognition test in patients with schizophrenia has been associated with deficits on attention and executive functioning,16 and rapid visual processing.17

Our objective for this study was to explore the ability of patients with schizophrenia to perceive affective prosody. More specifically, we were interested in whether these patients could perceive some, but not other, emotions. Finally, we explored gender differences in affect perception.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were 36 patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (14 women) and 32 healthy comparison subjects (9 women). All gave their consent to participate in this study. Patients with schizophrenia were recruited from the acute ward (9 inpatients who were evaluated after they had achieved sufficient symptom remission and shortly before they were discharged) and the outpatient service of a university psychiatric department (27 outpatients), while the healthy subjects were recruited from the community.

All patients were diagnosed according to DSM–IV criteria.18 Diagnosis was confirmed with the Greek version (translation-adaptation to the Greek language by S. Beratis) of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (4.4) (MINI).19 Ten patients had schizophrenia of the paranoid type, eight of the undifferentiated type, and 18 of the residual type. We assessed symptom severity (positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and general psychopathology) of the patients with schizophrenia with the Greek version20 of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).21 The Extrapyramidal Symptom Scale (ESRS)22 was used for measuring extrapyramidal symptoms. All of the patients were receiving antipsychotic medication at the time of the study. Twenty eight patients were on atypical antipsychotics; three were on typical antipsychotics; one was taking a combination of atypical and typical antipsychotics; and four were on a combination of two atypical antipsychotics. Anticholinergic drugs were administered to 15 patients.

Exclusion criteria for both groups included non-native Greek speakers, neurological and developmental disorders, head injury followed by loss of consciousness greater than 10 minutes, alcohol or drug abuse during the 6 months prior to the time of testing, and any physical illness that may have affected their cognitive performance. Additional criteria for healthy participants were a history of a psychiatric disorder or treatment as well as a family history of psychosis.

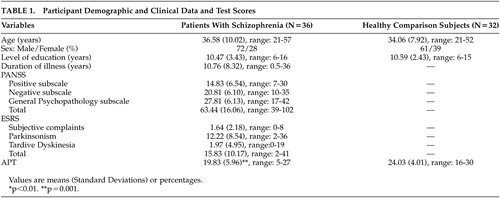

Demographic characteristics of the two groups and clinical data of the patients with schizophrenia are presented in Table 1.

Neuropsychological Assessment

Affective Prosody Test (APT).

In this test, 30 audiorecorded sentences of emotionally neutral content (e.g., “Today is Wednesday”) in Greek were presented with prosodic intonation by one male actor portraying one of the basic emotions (happiness, sadness, surprise, fear, and anger, as well as neutral) with five examples of each emotion (by one male actor).23 The participants had a list of the options in front of them and made their choice after each sentence. A training trial, in which participants heard a sentence with the above six prosodic intonations, preceded the experiment.

Statistical Analyses

Group comparisons (patients with schizophrenia and healthy comparison subjects) were conducted with one-way analyses of variance, when variables were continuous, and with chi-square tests, when variables were categorical.

RESULTS

Patients with schizophrenia and healthy comparison subjects did not differ significantly in demographic characteristics: age (F=1.30, df=1, 66, p=n.s.), male to female ratio (χ2=0.88, df=1, p=n.s.), and level of education (F=0.28, df=1, 66, p=n.s.) (Table 1).

The two groups differed significantly on the APT (F=11.32, df=1, 66, p=0.001), with patients with schizophrenia having lower scores than healthy participants (Table 1). The mean accuracy of the patients on the APT was 66.1% (SD=19.87), and that of healthy comparison subjects was 80.19% (SD=13.37). When we conducted the same analysis for men and women separately, only men with schizophrenia had significantly lower scores on the APT than healthy men (F=3.04, df=1, 43, p=0.001), while women of the two groups did not differ significantly (F=2.10, df=1, 21, p=0.16). The mean accuracy of men with schizophrenia was 61.07% (SD=21) versus 78.83% (SD=13.07) for the healthy men, and the mean accuracy of women with schizophrenia was 74.03% (SD=15.43) versus 83.33% (SD=14.43) for the healthy women.

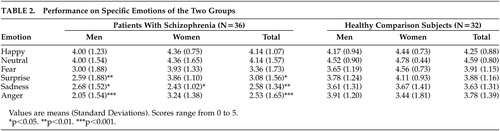

Regarding specific emotions, patients with schizophrenia as a group presented difficulties perceiving sadness (F=10.44, df=1, 66, p=0.002), anger (F=11.38, df=1, 66, p=0.001) and surprise (F=5.55, df=1, 66, p=0.021), but not happiness (F=0.22, df=1, 66, p=n.s.), fear (F=2.29, df=1, 66, p=n.s.) and neutral intonation (F=2.18, df=1, 66, p=n.s.) (Table 2). Specifically, male patients with schizophrenia presented worse recognition of anger (F=19.00, df=1, 43, p<0.001), sadness (F=4.82, df=1, 43, p=0.034), and surprise (F=15.97, df=1, 43, p=0.008) than healthy men, while female patients with schizophrenia showed worse performance than the healthy women on processing sadness (F=5.99, df=1, 21, p=0.023).

The rank order of the six emotions from highest to lowest mean scores was similar for both groups. For the healthy participants, the rank order was neutral intonation, happiness, fear, surprise, anger, and sadness, and for the patients, the rank order was neutral intonation, happiness, fear, surprise, sadness, and anger.

DISCUSSION

Patients with schizophrenia presented significant impairment in the recognition of affective prosody. This finding is in accordance with previous reports in the literature examining affective prosody recognition in schizophrenia.8–13

Women with schizophrenia present a more favorable social course than men. This sex difference in the social course of schizophrenia may reflect the protective effect of estrogen in women, accounting for the older age of onset of schizophrenia in women. Consequently, women manage to attain a higher level of social, and, possibly, cognitive and personality development before illness onset. Thus, their social functioning may be less impaired by the illness than men (for a review of gender differences in schizophrenia see Häfner).24 In accordance, women with schizophrenia have shown better absolute levels of verbal learning than males, although both groups were impaired relative to the general population.25 It is accepted that verbal memory deficits in schizophrenia have been associated with all types of functional outcome.26 In our study, only men with schizophrenia presented significant deficits on recognition of affective prosody compared with healthy men, whereas women of the two groups performed similarly on the APT. Affective prosody deficits in patients with schizophrenia have been found to be related to dysfunction in occupational performance.13 In another study, inaccurate “affect recognition,” which was a composite index based on measures of vocal and facial affect identification, was associated significantly with impoverished interpersonal relations, even after controlling for subject’s intellectual abilities and illness severity.27 In our study men with schizophrenia had more trouble with perception of affective prosody than women with schizophrenia, even than women would still have some difficulty when matched against comparison subjects. Sex-related deficits on affective prosody decoding might contribute to the well-documented sex differences in social functioning in schizophrenia. This gender differentiation could not be attributed to any significant differences in age, level of education, duration of illness, psychopathology, or schizophrenia type.

With regard to each emotion type separately, patients performed worse in anger, sadness, and surprise. Specifically male patients with schizophrenia presented worse recognition of anger, sadness, and surprise than healthy males, while female patients with schizophrenia showed worse performance only on processing sadness than healthy females. In general, the impairment in sadness and anger is in agreement with the negative valence hypotheses. Murphy and Cutting have suggested that the deficit in prosodic perception may be due to reduced performance on sadness.14 Edwards et al. also tracked down problems in the prosodic perception of negative emotions, specifically in fear and sadness.11 Studies in facial affect recognition also showed a specific deficit in recognition of negative emotions;4 specifically in facial identification of fear and sadness.11,28 Surprise is classified as neither a positive nor a negative emotion. Previous studies have failed to demonstrate a difference between the performance of patients and healthy participants on stimuli indicating surprise. Therefore, the lower score exhibited by our patients with schizophrenia in surprise prosody is difficult to explain.

Studies of brain damaged patients and brain functional imaging of healthy individuals exploring the neural structures by which human beings recognize emotion from prosody, have suggested that the recognition of emotional prosody draws on distributed and bihemispheric structures, with right inferior frontal regions (Brodmann’s area 10) being the most critical components of the system. These areas work together with more posterior regions in the right hemisphere (anterior parietal cortex), the left frontal regions, and subcortical structures (basal ganglia, amygdala), all interconnected by white matter.29,30 Regarding the amygdala, it has been suggested that its role in recognizing emotion in prosody might not be crucial.31,32 However, others have reported amygdala activation to emotional auditory stimuli.33,34 Ross et al. compared patients with schizophrenia, right brain damage, and left brain damage and proposed that impairment in affective prosody in schizophrenia results from right hemispheric dysfunction.12 Recently, a functional MRI study of a group of male patients with schizophrenia demonstrated a reversal of the normal right-lateralized temporal lobe response to affective prosody.35

Since there is a clear correlation between the level of difficulty of the APT for the healthy comparison subjects and the likelihood that the patients with schizophrenia would perform more poorly, we cannot determine whether there are true differential deficits in affect perception or whether these differences are due to psychometric artifact. Consequently, future research will need to address this issue.

In summary, patients with schizophrenia presented significant impairment in recognition of affective prosody compared with healthy subjects. This deficit was gender specific, as only men with schizophrenia presented significant impairment on recognition of affective prosody compared with healthy men. Finally, with regard to each emotion type separately, patients performed worse in emotions with negative valence, specifically anger and sadness. Future studies should also explore the consequences of these deficits on social and interpersonal functioning more directly.

|

|

1 Pinkham AE, Penn DL, Perkins DO, et al: Implications for the neural basis of social cognition for the study of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:815–824Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Green MF: Schizophrenia Revealed: From Neurons to Social Interactions. New York, Norton, 2001Google Scholar

3 Mueser KT: Cognitive functioning, social adjustment and long-term outcome in schizophrenia, in Cognition in Schizophrenia: Impairments, Importance and Treatment Strategies, Edited by Sharma T, Harvey P. New York, Oxford University Press, 2000, pp 157-177Google Scholar

4 Mandal MK, Pandey R, Prasad AB: Facial expressions of emotions and schizophrenia: a review. Schizophr Bull 1998; 24:399–412Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Edwards J, Jackson HJ, Pattison PE: Emotion recognition via facial expression and affective prosody in schizophrenia: a methodological review. Clin Psychol Rev 2002; 22:789–832Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Brüne M: Theory of mind and the role of IQ in chronic disorganized schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2003; 60:57–64Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Green MF, Kern RS, Robertson MJ, et al: Relevance of neurocognitive deficits for functional outcome in schizophrenia, in Cognition in Schizophrenia: Impairments, Importance and Treatment Strategies, Edited by Sharma T, Harvey P. New York, Oxford University Press, 2000, pp 178-192Google Scholar

8 Kerr SL, Neale JM: Emotion perception in schizophrenia: specific deficit or further evidence of generalized poor performance? J Abnorm Psychol 1993; 102:312–318Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Leentjens AFG, Wielaert SM, van Harskamp F, et al: Disturbances of affective prosody in patients with schizophrenia; a cross sectional study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998; 64:375–378Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Shaw RJ, Dong M, Lim KO, et al: The relationship between affect expression and affect recognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1999; 37:245–250Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Edwards J, Pattison PE, Jackson HJ, et al: Facial affect and affective prosody recognition in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2001; 48:235–253Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Ross ED, Orbelo DM, Cartwright J, et al: Affective-prosodic deficits in schizophrenia: profiles of patients with brain damage and comparison with relation to schizophrenic symptoms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001; 70:597–604Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Hooker C, Park S: Emotion processing and its relationship in schizophrenia patients. Psychiatry Res 2002; 112:41–50Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Murphy D, Cutting J: Prosodic comprehension and expression in schizophrenia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1990; 53:727–730Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Whittaker JF, Connell J, Deakin JFW: Receptive and expressive social communication in schizophrenia. Psychopathology 1994; 27:262–267Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Bozikas VP, Kosmidis MH, Anezoulaki D, et al: Relationship of affect recognition with psychopathology and cognitive performance in schizophrenia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2004; 10:549–558Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Kee KS, Kern RS, Green MF: Perception of emotion and neurocognitive functioning in schizophrenia: what’s the link? Psychiatry Res 1998; 81:57–65Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 American Psychiatric Association: DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994Google Scholar

19 Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al: The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 20):22-33Google Scholar

20 Lykouras E, Botsis A, Oulis P: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (in Greek). Athens, Tsiveriotis Ed., 1994Google Scholar

21 Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987; 13:261–276Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Chouinard G, Ross-Chouinard A, Annable L, et al: Extrapyramidal Rating Scale. Can J Neurol Sci 1980; 7:233Google Scholar

23 Hiou K, Vagia A, Haritidou E, et al: Affect perception as a cognitive function: validity and clinical application of a neuropsychological test battery in healthy individuals and patients with brain lesions. Psychology (in Greek) 2004; 11:308–401Google Scholar

24 Häfner H: Gender differences in schizophrenia. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003; 28(suppl 2):17-54Google Scholar

25 Sota TL, Heinrichs RW: Sex differences in verbal memory in schizophrenia patients treated with “typical” neuroleptics. Schizophr Res 2003; 62:175–182Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:321–330Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Poole JH, Tobias FC, Vinogradov S: The functional relevance of affect recognition errors in schizophrenia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2000; 6:649–658Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Archer J, Ay DC, Young AW: Movement, face processing and schizophrenia: evidence of a differential deficit in expressing analysis. Br J Clin Psychol 1994; 33:517–528Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Adolphs R: Neural systems for recognizing emotion. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2002; 12:169–177Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Adolphs R, Damasio H, Tranel D: Neural systems for recognition of emotional prosody: A 3-d lesion study. Emotion 2002; 2:23–51Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Adolphs R, Tranel D: Intact recognition of emotional prosody following amygdala damage. Neuropsychologia 1999; 37:1285–1292Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 Royet JP, Zald D, Versace R, et al: Emotional responses to pleasant and unpleasant olfactory, visual, and auditory stimuli: a position emission tomography study. J Neurosci 2000; 20:7752–7759Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 Scott SK, Young AW, Calder AJ, et al: Impaired auditory recognition of fear and anger following bilateral amygdala lesions. Nature 1997; 385:254–257Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 Morris JS, Scott SK, Dolan RJ: Saying it with feelings: neural responses to emotional vocalizations. Neuropsychologia 1999; 37:1155–1163Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 Mitchell RLC, Elliott R, Barry M, et al: Neural response to emotional prosody in schizophrenia and in bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2004; 184:223–230Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar