Electroencephalographic Cerebral Dysrhythmic Abnormalities in the Trinity of Nonepileptic General Population, Neuropsychiatric, and Neurobehavioral Disorders

Although the existing EEG literature is replete with reports of abnormalities in association with different neuropsychiatric disorders, only a few generalizations can be made between particular EEG patterns and disorders. The strong (and relatively straightforward) correlation that has been established between EEG abnormalities and epilepsy has overshadowed the more complex relationship between EEG abnormalities and psychiatric disorders. Moreover, the prevailing concept of “not treating the EEG” led to further de-emphasizing such EEG deviations. These issues prompted us to critically and systematically reappraise the extensive available literature, which spanned almost six decades, on EEG dysrhythmia to dissect the EEG-behavior equation, address the merits and demerits of various studies, and examine the validity of such EEG findings in the current environment of evidence-based medicine. The interested reader is referred to the reviews of Hill & Parr 3 on EEG correlates of psychopathic behavior and schizophrenia, and Glaser 4 on EEG correlates of human behavior for a historical perspective.

This article does not address the “pearls, perils and pitfalls” in the use of EEG in epilepsy but instead reiterates that epileptiform and other paroxysmal EEG dysrhythmias unrelated to clinical seizures do occur in neuropsychiatric and behavioral disorders.

While the mainstay for use of EEG in psychiatry has been in differentiating brain disease from primary psychiatric disorders, the recent advances in EEG and other electrophysiology techniques have emerged as powerful tools in the exploration of the biological substrate for neuropsychiatric disorders. We propose that once the clinical correlates and the underlying pathological processes of such aberrations are understood, such knowledge will significantly contribute to our understanding of the basic pathophysiology underlying psychiatric symptomatology where such aberrations are evident. Research in this area can also contribute to developing better biopsychosocial formulations and better treatment plans for individual patients.

METHOD

An extensive search of the literature included in the MEDLINE database for the period of 1950 to 2005 was performed. The first step was a general search for EEG abnormalities in nonepileptic subjects, healthy patients, and in the general community using multiple search terms. Papers examining EEG in nonepileptic populations were then identified via article titles and abstracts. The MEDLINE and textbook chapters discussing “normal EEG” and “EEG and psychiatry” were then examined for references. These two sources were the primary sources for references. The reference lists of each paper or book chapter were searched for older relevant papers. For inclusion in our review, papers had to be in English.

Second, a number of narrower searches were conducted for EEG abnormalities and individual disorders discussed in this paper. Papers not examining the conventional EEG, examining sleep, quantified EEG, or event-related potentials were excluded. Next, searches were performed for all studies examining the clinical correlates of the so-called “controversial EEG waveforms.” Finally, a search for EEG abnormalities in pediatric neurobehavioral disorders was conducted with similar methodology and exclusions.

In this article, EEG cerebral dysrhythmia denotes isolated episodic paroxysmal bursts of slow activity, controversial/anomalous spiky waveforms and/or true non-controversial epileptiform discharges.

RESULTS

EEG Dysrhythmia in the Nonepileptic Population

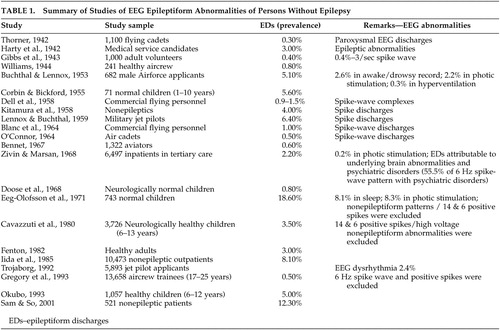

Twenty-two papers were identified. Epileptiform discharges (EDs) ranged from 0.8% to 18.6% in reportedly normal children and 0.3% to 12.3% in reportedly normal adults. These studies have been summarized in Table 1 .

|

Several of these investigations had attempted to determine the prevalence of such epileptiform discharges in large “healthy” nonepileptic populations. In this regard, several publications have reported a wide range of prevalence of varying EEG dysrhythmia, some of which were in disagreement, in nonepileptic and purported normal populations. The results of such studies, unfortunately, therefore depicted conflicting EEG findings within the “healthy” nonepileptic populations.

It can be seen from Table 1 that there were studies with relatively low rates of epileptiform discharges, and on the contrary, several studies did document a high prevalence of epileptiform discharges. The low estimates, as in the studies of Gibbs et al. (0.4%) 5 and Bennet (0.6%), 6 employed minimum EEG requirements, where only three head regions were examined, without a sleep record, and for a limited duration of 10–15 minutes. Bennett’s study focused only on spike-wave abnormalities and excluded all other epileptiform discharges. Eeg-Olofsson et al. 7 reported a high prevalence of epileptiform discharges but they considered all the EEG dysrhythmia in children during wakefulness, in addition to studies during sleep, photic stimulation, and hyperventilation, and they included non-epileptiform activities as well.

In other studies, factors that were incriminated in high prevalence estimates were the inclusion of individuals with psychiatric histories and/or history of significant head trauma. For instance, in a series of 6,497 nonepileptic subjects, Zivin and Marsan 8 had reported the prevalence of epileptiform discharges to be 2.2% when careful definitions of epileptiform discharges had been used with optimum recording standards. In this nonepileptic group, epileptiform discharges were attributable to underlying brain abnormalities (traumatic, vascular, tumor, metabolic), medications, and psychiatric disorders. The prevalence of epileptiform discharges in these groups was reported as 5.5% in those with mental handicap, 9.8% with congenital or perinatal brain insults, 10.6% after cranial operations, and 8.2% in individuals with cerebral tumors.

A similar conclusion was derived from a study of patients without epilepsy in the community. In this study, the prevalence of epileptiform discharges was reported as 12.3%, but 73.4% of the nonepileptic patients had underlying cerebral disorders. 9 This emphasized that the presence of epileptiform discharges in subjects without epilepsy should be inferred as “electrographic markers” of underlying brain dysfunction without the vulnerability to clinical seizures. These abnormal neuronal discharges, most closely associated with seizures, do occur in people who do not have epilepsy (subclinical epileptiform discharges), but most have been linked to underlying cerebral disorder.

After exclusion of contaminating factors, the true prevalence of epileptiform discharges in the healthy normal population should be extremely low. The current estimate of EEG epileptiform dysrhythmia in the nonepileptic healthy population should be less than 1%, as supported by the work of Gregory et al. 10

Struve 11 reported the prevalence of EEG abnormalities in the nonepileptic “normal” adult population ranging from 4% to as high as 57.5%. This wide range reflected the lack of rigorous selection criteria for choosing the normal healthy control comparison subjects. A study by Boutros et al. 12 emphasized the priority for clearly defining the boundaries of the normative EEG, which is critical in deriving valid generalizations for consensus opinion on the electroencephalographic correlates of neuropsychiatric disorders. They proposed a seven point normality criteria for selecting healthy comparison subjects. Their search of the relevant published literature on selection methodology for “normal” comparison subjects from 1936 to 2005 included 38 articles. The majority of included studies did not fulfill any of their specified normality criteria. The study confirmed the inadequate definition for EEG normality, and also reiterated the fact that the literature concerning the prevalence or significance of EEG correlates in neuropsychiatry remains preliminary after all these years.

EEG Dysrhythmia in Neuropsychiatric Disorders

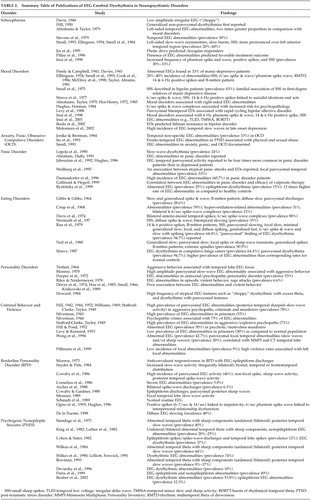

Sixty-three papers were identified. Ten papers examined the conventional EEG in schizophrenia populations ( Table 2 ). Eight of the 10 papers reported varying degrees of abnormalities and two papers reported that such deviations may be related to treatment responses. Eighteen papers were related to mood disorders and reported varying degrees of abnormalities. Eleven papers addressed anxiety disorders (including panic attacks), seven addressed eating disorders, 20 addressed personality disorders (11 of those on borderline personality disorder), 12 papers addressed criminal behavior and violence, and 11 papers examined the EEGs of patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. The overwhelming majority of papers reported varying degrees of abnormalities ( Table 2 ).

|

During the last six decades there has been a large amount of literature on electroencephalographic abnormalities in a high proportion of psychiatric patients. No comprehensive review of this large body of psychiatrically relevant literature has been critically presented. Our extensive search of publications on the EEG correlates of psychopathology is summarized in Table 2 . The published work of Kennard 13 reviewed two decades of pioneering literature affirming the positive correlations of abnormal EEGs in psychological disorders. This section, even after six decades of psychiatric EEG research, attempts to dissect the same behavioral/EEG equation as it applies to our current state of EEG understanding and evidence-based research methodology.

About two decades earlier, the work of Bridgers 14 again confirmed the occurrence of epileptiform dysrhythmic abnormalities in a population of nonepileptic hospitalized psychiatric patients. The EEG findings were found to correlate with conditions such as anorexia nervosa, depression, mania, personality disorders, suicidality without depression, schizophrenia, nonpsychotic explosive behavior, and the effects of psychotropic medications. The epileptiform EEG abnormalities were documented in 2.6%, and consisted of photoparoxysmal responses, focal temporal complexes, generalized spike-wave or polyspike-wave discharges, and focal central/frontal complexes. This study did emphasize that EEG epileptiform dysrhythmia does occur in nonepileptic psychiatric populations and may reflect underlying cerebral dysfunction without necessarily indicating an increased liability to seizures.

Numerous studies have documented conventional EEG abnormalities in 20%–60% of patients with schizophrenia, and have been summarized in Table 2 . Abrahams and Taylor 15 showed that schizophrenic patients had twice as many left-sided temporal abnormalities than patients with affective disorders who had more right-sided EEG findings. Definite EEG abnormalities have been documented in a high proportion of schizophrenia patients, but perhaps were minor, quite nonspecific, and conjectural. EEG abnormalities were more frequent in the cohort of schizophrenic patients who had a positive family history suggesting that genetic factors may be contributing to EEG traits. The EEG aberrations possibly reflected abnormalities in cortical neuronal architecture, cellular neuropathology, and neurochemical transmitter abnormalities that underpin the schizophrenia pathophysiology, in addition to possible neuroleptic medication effects. These EEG aberrations, along with neuroimaging and neuropsychological abnormalities, lend objective evidence for brain dysfunction in the genesis of schizophrenia. Furthermore, specific differences have also been reported among subgroups of functional mental illness. Psychotic mood disorders and “atypical” psychoses are reported to have a higher frequency of epileptiform variants, including the phantom spike and wave, positive spikes, and small sharp spikes, as compared with nonpsychotic mood disorders and schizophrenia. 16

Many previous EEG findings in individuals with personality disorders, violent and criminal behavior, and forensic populations have been found to suffer from methodological problems. The EEG data were thus considered nonspecific as the results could not always be replicated by all investigators. Therefore, the significance of these EEG abnormalities is still a matter of debate. Abnormal EEG findings reported in association with personality disorders, criminal behavior, and borderline personality disorder are summarized in Table 2 . One of the interesting findings in earlier studies was that relatively good personality structure relates to a normal EEG. 17 The initial studies did reveal positive trends in relating EEG dysrhythmic abnormalities to personality traits, and a psychopathic MMPI profile. 17 – 19 These EEG aberrations noted in personality disorders and impulsive behaviors reflect the presence of cerebral dysfunction that may hamper the natural process of psychological maturation.

Hill and Watterson 18 were the first to postulate that EEG dysrhythmia in aggressive psychopaths reflected a failure in functional cortical development (maturational retardation hypothesis). Although some evidence supports the maturational retardation hypothesis, 20 , 21 the finding that many aggressive psychopaths had normal EEGs argued against it. Other studies, however, failed to find a relationship between EEG abnormalities and aggressive tendencies. 22 – 25 Ribas et al., 26 on the other hand, found evidence of cerebral dysrhythmia in 69% of youngsters with behavior disorders with a predominance of aggressiveness. Earlier literature did link criminal behavior and aggression to an “epileptic etiology.” However, there is lack of convincing current evidence for such a proposition of an association between violence and epileptiform EEG disturbances. 27

Studies of antisocial and criminal populations have revealed EEG abnormalities in 24%–78% of individuals. These EEG abnormalities were found to be more prevalent in subjects with violent crimes, repeated violence, and motiveless crimes. No specific relationship had been found between the type of EEG abnormality and characteristics of the crime, or between EEG changes and the degree of violence committed. 28 , 29 Several types of EEG abnormalities have been found in violent offenders: generalized slowing, focal slowing, and epileptiform discharges. A few studies summarized in Table 2 had established violent behavior to be linked to left-sided temporal lateralization of EEG abnormalities. 28 , 30 These EEG aberrations suggested an underlying brain dysfunction in violent behavior. 31 The validity of these EEG aberrations has also been confirmed by quantitative EEG 32 and neuropsychological data. 33 These studies lend support to the concept of a connection between left hemispheric (frontal, temporal) cerebral dysfunction and the propensity for violence. However, the presence of EEG dysrhythmia, instead of having any specific associations with criminal behavior, may actually represent underlying comorbid factors such as multiple head injuries, coexisting substance abuse, and associated toxic and metabolic disorders, although a laterality effect would not be expected.

In borderline personality disorder (BPD), the literature suggests two types of conventional EEG abnormalities: epileptiform dysrhythmia and diffuse EEG slowing. The presence of epileptiform discharges in bipolar disorder possibly indicates cortical excitability disturbances that may be predictive of responsiveness to anticonvulsant therapy, 29 whereas diffuse EEG slowing possibly reflects underlying metabolic or degenerative etiologies. Boutros et al. 34 reviewed the literature from 1966 to 2000 on the electrophysiological aberrations in bipolar disorder. It was found that the EEG investigations of bipolar disorder were limited, as only nine articles could be retrieved. Furthermore, the majority did not have adequate control groups or adequate evaluation of Axis I or Axis II comorbidity and controls for medication effects.

Anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders have also been documented to have a higher prevalence of EEG dysrhythmia. EEG abnormalities documented include 14 and 6 positive spikes, B-mitten patterns, small sharp spikes, paroxysmal slowing, focal slowing, minimal generalized slowing, focal & diffuse spiking, generalized fast, 6/sec spike and wave and slow with spiking. The co-occurrence of EEG abnormalities consisting of B-mitten and small sharp spike (SSS) dysrhythmic patterns may reflect the cross relationships between anorexia nervosa, depressive disorder, and suicidality. These are possibly related to dietary factors, neuroendocrine, and nutritional deficiencies that would undoubtedly cause cerebral metabolic aberrations contributing to brain dysfunction.

As seen in Table 2 , several studies have suggested a high incidence of EEG abnormalities in patients with anxiety disorders, panic disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorders. Hughes 35 reported that EEG paroxysmal dysrhythmia was four times more common in panic patients than in depressed patients. Our literature review indicated that about 25%–30% of panic attack patients had demonstrable EEG abnormalities, especially in atypical presentations of panic attacks. Some studies have documented an epileptic pathophysiology to underlie atypical panic attacks. 36

Our literature review ( Table 2 ) suggests that the incidence of abnormal EEG findings in mood disorders is substantial, ranging from 20%–40%. 37 , 38 , 39 – 41 These abnormalities were found to be higher in manic patients than in depressed patients, in female than in male bipolar patients, and in nonfamilial cases with late-age onset disorder. Specific patterns noted in mood-disorders include the small sharp spikes (SSS), 6/sec spike and wave complexes (RMTD), B-mitten pattern, and positive spikes. Abrahams and Taylor 15 and Flor-Henry 42 , 43 reported that mood disorders particularly showed more right-sided EEG abnormalities, in contrast to the left temporal EEG abnormalities in schizophrenia. Further, a few reports have demonstrated that rapid cycling bipolar affective disorder patients had more prevalent EEG evidence of bitemporal epileptiform paroxysmal activities than patients with nonrapid cycling mood disorders. 44

Head injury with post-concussion syndromes may have a high incidence of underlying diffuse axonal injury and have been documented to be associated with abnormal EEGs, even in the presence of normal neurological examinations. 45 Thus, as pointed out earlier in the section ”EEG Dysrythmia in the Nonepileptic Population,“ head injury should form an exclusion criterion in the selection of healthy comparison groups in neuropsychiatric research.

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizure (PNES) is another area in the psychiatric EEG literature that merits a reappraisal. In our review of the literature, the only study that specifically focused on the prevalence of interictal EEG abnormalities in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures was that of Reuber et al. 46 Other studies related to psychogenic nonepileptic seizures have been summarized in Table 2 , and relevant data extracted from these articles pointed to a mean prevalence of interictal EEG abnormalities in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures to be estimated at 25.9%. 47 – 55 In Reuber’s study, the rates of abnormal, non-specific, and epileptiform EEG abnormalities in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures were documented to be 53.8% and 12.3%, respectively. When psychogenic nonepileptic seizures were compared with an appropriately selected control group, nonspecific EEG abnormalities were seen 1.8 times as often in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures as in healthy controls. Such EEG abnormalities may be attributed to the complex interaction of comorbid psychiatric disorders and various psychopathological variables, underlying brain abnormalities, head trauma, 56 – 58 and physical and sexual abuse, which plays a pivotal role in the final clinical expression of psychogenic nonepileptic seizure vulnerability. It is imperative to be cognizant of the fact that EEG dysrhythmias do occur in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, and it is crucial to understand that the mere presence of paroxysmal EEG dysrhythmia in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures should not lead to an epileptic connotation.

Early childhood sexual abuse, early stress, and lifetime assaultive violence have been linked to cortical maldevelopment and increased electrophysiological abnormalities. Several studies reported that such severe early stress and abuse have the potential to alter brain development and cause limbic dysfunction during specific sensitive periods of cortical maturation. 59 The cascade of events is mediated through stress-induced neurohormones of the glucocorticoid, noradrenergic, and vasopressin-oxytocin stress response systems which affects neurogenesis, synaptic overproduction and pruning, and myelination. The aberrant cortical development has been reported to involve the corpus callosum, 60 left neocortex, hippocampus, and amygdala. During the last decade, studies have reported an emergence of EEG abnormalities in children with sexual and psychological abuse. An increased prevalence of fronto-temporal electrophysiological abnormalities with a left-sided localization was reported in abused children. 61 – 63 Another study reported dysrhythmic EEG abnormalities in 77% (N=22) of patients who were involved as the child or younger member in an incestuous relationship, of which 36% had clinical seizures. 64 These studies thus provide evidence for the neurobiological underpinnings through which early abuse increases the risk of developing various psychopathologies and its electrophysiological consequences.

Clinical Correlates of Controversial/Anomalous EEG Patterns

Significant literature pertaining to each of five “controversial” patterns was found. Of nine papers examining the correlates of the rhythmic mid-temporal discharges (RMTD), six found psychiatric correlates. Similarly, six of nine papers examining the Wicket spikes/Mu rhythm found psychiatric correlates. The pattern with most attention is the 14 and 6 positive spikes. Of 17 papers examining this pattern 10 reported psychiatric correlates. Seven of 13 papers examining small sharp spikes reported clinical correlates while all six papers examining the 6/second spike and wave pattern reported clinical psychiatric associations.

Our literature review on controversial/anomalous patterns revealed numerous reports of a high prevalence of these patterns associated with various neuropsychiatric disorders. Some of these patterns have been reported to occur in normal individuals, and hence have been referred to as “benign epileptiform variants.” Such attributes of the various patterns have been summarized in Table 3 . Despite the repeated demonstration of a higher prevalence in psychiatric populations, these EEG patterns were deemed “normal variants” or considered controversial and have been the subject of well-designed investigations. Notwithstanding the increased prevalence of these EEG patterns in neuropsychiatric disorders, their neurobiological and genetic basis, and neural source generators have not been clearly elucidated. There have also been no studies over the last few decades specifically addressing these controversial patterns and their psychiatric relevance.

|

EEG Dysrhythmia in Pediatric Neurobehavioral Disorders

Twelve papers were identified addressing autistic spectrum disorders. All papers reported increased prevalence of EEG abnormalities ranging from 5.7%–60.7% ( Table 4 ). Five of the six papers examining the EEGs of patients with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome reported abnormal EEGs, as well as the six papers investigating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

|

Two of the common neurobehavioral disorders of childhood are autistic spectrum disorders (autism, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified, Asperger’s syndrome, Rett’s syndrome, and disintegrative disorder) and attention deficit disorders with or without hyperactivity (ADHD or attention deficit disorder). Autistic spectrum disorders, Landau-Kleffner syndrome, electrical status in slow wave sleep, developmental dysphasia, and benign rolandic epilepsy have overlapping features, and from our review, the high incidence of epilepsy and/or subclinical or infraclinical epileptiform EEG dysrhythmia does seem to be the interesting common thread that exists among these conditions. The studies that have linked the various pediatric neurobehavioral disorders without overt clinical seizures to EEG abnormalities have been summarized in Table 4 .

The earliest review of studies on autism was contributed by Small et al. 65 who, from 14 pooled studies, reported a wide range of prevalence of EEG dysrhythmia. This large range undoubtedly arose from differences both in the populations under study and, more importantly, the diagnostic criteria used for the abnormality. Kim et al. 66 reported 59% prevalence of interictal epileptiform EEG abnormalities that included focal sharp waves, multifocal sharp waves, generalized spike-wave complexes, and generalized paroxysmal fast activity/polyspikes in nonepileptic autistic children. These EEG dysrhythmias probably represent an age-dependent epiphenomenon of impaired brain maturation, with cumulative effects of these EEG discharges contributing to cognitive abnormalities.

Several studies summarized in Table 4 have documented positive correlations between subclinical paroxysmal EEG dysrhythmia in nonepileptic autism 67 – 74 and nonepileptic ADHD, 75 – 78 and have also brought to light the clinical overlap between nonepileptic ADHD and typical benign rolandic epilepsy as evidenced by the increased frequency of EEG subclinical rolandic spikes in these nonepileptic groups. 79

The electrographic dysrhythmia in these pediatric neurobehavioral disorders may represent an epiphenomenon of cerebral dysfunction or underlying cortical morpho-functional abnormalities, and/or reflect a brain neurophysiological disorder which is not sufficient to be expressed as epilepsy. This may be due to the lack of properly functioning corticocortical fibers which restricts the spread of epileptiform activity from one brain area to another and prevents its evolution to a clinical seizure. The “subclinical epileptogenesis” in the developing brain may also directly impair cognitive behavior functioning by way of “transient cognitive impairment” mechanisms, well described by Binnie and his colleagues. 80 – 82 A complicated evolution in benign rolandic epilepsy had been reported to occur in a proportion of benign rolandic epilepsy patients. This benign rolandic epilepsy subset developed behavioral, cognitive, and learning problems independent of their clinical seizures or treatment. The complicated evolutions were found to be correlated with certain interictal EEG variables: intermittent slow-wave focus, multiple asynchronous spike-wave foci, long spike-wave clusters, and generalized 3 Hz “absence-like” spike-wave discharges. 83 Complicated benign rolandic epilepsy does further implicate the role of subclinical interictal EEG discharges in the etiology of behavioral and cognitive problems unrelated to any seizure characteristics.

The studies summarized in Table 4 put forward arguments for an association between subclinical epileptiform discharges and neurobehavioral disorders as well as about causality. Given the established link between EEG epileptiform abnormalities and neuropsychiatric symptoms in these overlapping disorders, EEG evaluation seems to be justified in children with cognitive and behavioral problems, even in the absence of overt clinical seizures. In this context, Engler et al. 84 showed beneficial effects of sulthiame on EEG features, neuropsychological deficits, and speech deficits in seizure-free children with rolandic spikes. Duane et al. 85 reported similar findings in their study demonstrating beneficial effects on cognitive, behavioral, and EEG indices using levetiracetam in those with learning and attention problems. In a recent study, Chez et al. 74 reported a frequency of 60.7% abnormal EEG epileptiform activity in autism spectrum disorder patients with no known genetic conditions, brain malformations, prior medications, or clinical seizures. In the valproate treated group, 45% normalized on EEG and about 20% showed EEG improvement when compared with the first EEG.

At the end of this section, we opine that the maxim “treat the patient, not the EEG” may perhaps be an oversimplified clinical standpoint as evidence is mounting that some of the disorders reviewed (autism spectrum disorder, ADHD associated with subclinical rolandic epileptiform EEG discharges) with coincident subclinical epileptiform discharges might benefit from antiepileptic therapy even in the absence of overt clinical seizures. 86 , 87

DISCUSSION

During the 60 years in which electroencephalography has been studied, it has become evident that EEG cerebral dysrhythmia does exist in behavioral and psychiatric disorders, as shown by this review. At the end of this article, keeping in mind the extensive EEG data summarized in the various tables, a few pertinent questions emerge as to the significance and relevance of this large body of literature: Is there truly a high prevalence of abnormal EEG findings in nonepileptic individuals with behavioral disorders and psychopathology? What could be the underlying contributory factors that led to these EEG dysrhythmic aberrations? What are the practical/research implications of these EEG abnormalities?

We will now attempt to address these questions. From our review, there is a broad consensus that conventional EEG does reveal abnormalities in neuropsychiatric disorders. Although such results could not always be replicated by a few investigators, the vast majority of studies were in favor of a positive correlation. EEG aberrations reflected biological vulnerabilities to various psychiatric disorders and psychopathologies and are electrographically represented by EEG dysrhythmias. However, unlike the linear relationship observed between EEG abnormalities and some neurological disorders, the agreement is limited in terms of conventional EEG data in neuropsychiatric disorders. The lack of valid generalizations for conventional EEG abnormalities in neuropsychiatric populations could be attributed to several factors. Several studies were plagued by methodological defects, lack of controls, small sample size, differences in EEG interpretative criteria, lack of definitive psychiatric diagnostic criteria applied, and by the inadequate selection criteria for a healthy EEG control comparison group, which is a crucial element in neuropsychiatric EEG research. The majority of initial studies were performed prior to the publication of the DSM-III and IV criteria. At this point in time, our reappraisal of EEG associations in neuropsychiatric disorders is one of statistical and inferential value, and perhaps the existing literature still reflects a preliminary stage of the area.

From our search, a number of additional factors that contributed to the poor definition of the boundaries of normative EEGs have emerged. These factors include considerable variability and lack of homogeneity in the types of subjects examined, the small sample sizes in a number of studies, nonuniformity, and lack of technical standardization of the EEG methodology used in many of the earlier studies, lack of accurate EEG classification criteria for epileptiform discharges, and the lack of semi quantitative grading systems for EEG abnormalities. Many studies used observations made before strict criteria for noncontroversial epileptiform discharges were recognized, and therefore included the benign nonepileptogenic epileptiform or other controversial anomalous EEG patterns.

The heterogeneity of conventional EEG abnormalities in schizophrenia and mood disorders perhaps can be, to a large extent, attributed to medication effects. While many studies that we reviewed here were comprised of unmedicated subjects, several studies had not examined the effects of psychotropic medications on EEG. These factors do not, however, sufficiently explain the observed laterality differences in schizophrenia and mood disorders. We are cognizant of the fact that there is a widespread clinical use of antiepileptic drugs in such psychiatric patients. Pharmaco-EEG is a potential application in the future that will provide sensitive methods to monitor psychotropic drug therapy, and would have a role in the prediction of clinical response to treatment with psychotropic drugs. 88

The EEG abnormalities that are seen to underlie neuropsychiatric disorders reflect unequivocal evidence of underlying brain dysfunction at the cortical, neuronal architectural level, as well as neurochemical perturbations that underpin several psychiatric pathophysiologies. In addition, EEG abnormalities represent the phenotypic expression of cellular and biochemical dysfunction, and are also indicative of maturational retardation factors, possibly genetically determined, underlying subclinical earlier organic brain damage, neurotransmitter imbalance, or morpho-functional disturbances that may be present in neuropsychiatric disorders. The EEG is indeed a powerful tool in the exploration of the biological substrate for neuropsychiatric disorders. Currently, an increasing body of knowledge from brain imaging research has implicated brain abnormalities in the etiology of psychopathic and antisocial behavior. Functional brain imaging techniques such as fMRI and PET are certainly tools to further explore the existing relationship between the EEG, brain dysfunction, and deviant personality traits.

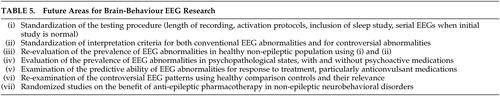

As far as pediatric neurobehavioral disorders discussed in the section “EEG Dysrythmia in Pediatric Neurobehavioral Disorders,” are concerned, further research is needed to explore and ascertain whether these electrophysiological aberrations are a cause, consequence, epiphenomenon, or a coincidence. The clinical overlaps between autism, ADHD, benign rolandic epilepsy, and Landau-Kleffner syndrome have received relatively little attention, and future studies need to focus on this EEG-behavior relationship. There is also no current consensus on whether treatment of EEG abnormalities in these disorders does improve behavior. The benefit of anti-epileptic pharmacotherapy for non-epileptic children with behavioral problems and EEG epileptic discharges must be clarified. 89 Randomized studies involving blinded pre- and post-treatment assessments of behavioral, cognitive, and neuropsychological domains as outcome measures will be needed to answer this question. Therefore, from an evidence-based research perspective, well-designed larger studies with adequately selected control comparison group, adequate diagnostic construct, and blinded EEG interpretations are needed in the future to reevaluate and confirm the precise relationship of the behavioral/EEG equation as outlined in Table 5 .

|

CONCLUSIONS

This review has critically and systematically reappraised the published electroencephalographic correlates of human behavioral disorders, and placed this subject into the current perspective. Despite the difficulty in drawing direct inferences from the vast volume of EEG literature, the reported EEG dysrhythmias suggest underlying brain dysfunction to be common among behavioral and neuropsychiatric disorders. It is important for both the neurologists and psychiatrists to recognize that paroxysmal EEG dysrhythmias do occur in the various disorders at the brain-mind interface that are not associated with overt clinical epileptic seizures. Emphasis has been placed on the need for future prospective evidence-based research to further revalidate the existing relationship between EEG and behavior/psychopathology. Electrophysiological investigations in neuropsychiatric disorders have the potential to contribute to our understanding of the different pathophysiological processes that may be aberrant in these disorders.

We would conclude that neuropsychiatric and/or neurobehavioral electrophysiology holds an exciting future promise by striving to combine different complimentary electrophysiological test modalities such as sleep EEG; quantitative EEG; magnetoencephalography; transcranial magnetic stimulation; evoked potentials; and EEG neurofeedback. The neurobehavioral electrophysiology data can be further verified with the current functional neuroimaging techniques: functional MRI and PET. Dissecting the behavioral phenotypes and their EEG associations will certainly help in further explicating the broader relationship between brain and behavior: the domain of “neurobehavioral electrophysiology.” The quotation by Stevens 90 that “all that spikes is not fits” is still relevant, and particularly true in the field of neuropsychiatry and behavioral neurology as illustrated in this review.

1 . Berger H: Über das Elektroenzephalogramm des Menschen. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten 1929; 87:527–570Google Scholar

2 . Hill D: Psychiatry, in Electroencephalography. Edited by Hill D, Parr G. London, MacDonald, 1950, pp 319–363Google Scholar

3 . Hill D, Parr G (eds): Electroencephalography: A Symposium on its Various Aspects. London, MacDonald, 1963Google Scholar

4 . Glaser GH: EEG and Behavior. New York, Basic Books, 1963Google Scholar

5 . Gibbs FA, Gibbs EL, Lennox WG: Electroencephalographic classification of epileptic patients and control subjects. Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1943; 50:111–128Google Scholar

6 . Bennett DR: Spike-wave complexes in “normal” flying personnel. Aerospace Med 1967; 38:1276–1282Google Scholar

7 . Eeg-Olofsson O, Petersen I, Sellden U: The development of the EEG in normal children from the age of 1 through 15 years: paroxysmal activity. Neuropaediatrie 1971; 2:375–404Google Scholar

8 . Zivin L, Ajmone Marsan C: Incidence and prognostic significance of “epileptiform” activity in the EEG of nonepileptic subjects. Brain 1968; 91:751–777Google Scholar

9 . Sam MC, So EL: Significance of epileptiform discharges in patients without epilepsy in the community. Epilepsia 2001; 42:1273–1278Google Scholar

10 . Gregory RP, Oates T, Merry RT: EEG epileptiform abnormalities in candidates for aircrew training. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1993; 86:75–77Google Scholar

11 . Struve FA: Clinical electroencephalography as an assessment method in psychiatric practice, in Handbook of Psychiatric Diagnostic Procedures, vol 2. Edited by Hall RC, Beresford TP. New York, Spectrum Publications, 1985, pp 1–48Google Scholar

12 . Boutros NN, Mirolo HA, Struve F: Normative data for the unquantified EEG: examination of adequacy for neuropsychiatric research. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005; 17:84–90Google Scholar

13 . Kennard MA: The EEG in psychological disorders: a review. Psychosom Med 1953; 15:95–115Google Scholar

14 . Bridgers SL: Epileptiform abnormalities discovered on electroencephalographic screening of psychiatric inpatients. Arch Neurol 1987; 44:312–316Google Scholar

15 . Abrahams R, Taylor MA: Differential EEG patterns in affective disorder and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 36:1355–1358Google Scholar

16 . Inui K, Motomura E, Okushima R, et al: Electroencephalographic findings in patients with DSM-IV mood disorder, schizophrenia, and other psychotic disorders. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 43:69–75Google Scholar

17 . Williams D: Neural factors related to habitual aggression: consideration of differences between those habitual aggressives and others who have committed crimes of violence. Brain 1969; 92:503–520Google Scholar

18 . Hill D, Watterson D: Electroencephalographic studies of psychopathic personalities. J Neurol Psychiatry 1942; 5:47–65Google Scholar

19 . Greenblatt M: Age and electroencephalographic abnormality in neuropsychiatric patients: a study of 1593 cases. Am J Psychiatry 1944; 101:82Google Scholar

20 . Kiloh L, Osselton J: Clinical electroencephalography. London, Butterworth, 1966Google Scholar

21 . Murdoch B: Electroencephalograms, aggression and emotional maturity in psychopathic and nonpsychopathic prisoners. Psychologia Africana 1972; 14:216–231Google Scholar

22 . Knott J, Gottlieb J: EEG in Psychopathic personality. Psychosom Med 1943; 5:139–142Google Scholar

23 . Arthurs R, Cahoon E: A clinical and electroencephalographic survey of psychopathic personality. Am J Psychiatry 1964; 120:875–877Google Scholar

24 . Loomis S: EEG abnormalities as a correlate of behavior in adolescent male delinquents. Am J Psychiatry 1965; 121:1003–1006Google Scholar

25 . Stevens J, Milstein V: Severe psychiatric disorders of childhood, EEG and clinical correlations. Amer J Dis Child 1970; 120:182–192Google Scholar

26 . Ribas JC, Baptistete E, Fonseca CA, et al: Behavior disorders with predominance of aggressiveness, irritability, impulsiveness, and instability: clinical electroencephalographic study of 100 cases. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria 1974; 32:187–194Google Scholar

27 . Driver MV, West LR, Faulk M: Clinical and EEG studies of prisoners charged with murder. Br J Psychiatry 1974; 125:583–587Google Scholar

28 . Pillmann F, Rohde A, Ullrich S, et al: Violence, criminal behavior, and the EEG: significance of left hemispheric focal abnormalities. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1999; 11:454–457Google Scholar

29 . Monroe RR: Anticonvulsants in the treatment of aggression. J Nerv Ment Dis 1975; 160:119–126Google Scholar

30 . Wong MT, Lumsden J, Fenton GW, et al: Electroencephalography, computed tomography and violence ratings of male patients in a maximum-security mental hospital. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 90:97–101Google Scholar

31 . Weiger WA, Bear DM: An Approach to the neurology of aggression. J Psychiatr Res 1988; 22:85–98Google Scholar

32 . Convit A, Czobor P, Volavka J: Lateralised abnormality in the EEG of persistently violent psychiatric inpatients. Biol Psychiatry 1991; 30:363–370Google Scholar

33 . Miller L: Neuropsychological perspectives on delinquency. Behav Sci Law 1988; 6:409–428Google Scholar

34 . Boutros NN, Torello M, McGlashan TH: Electrophysiological aberrations in borderline personality disorder: state of the evidence. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2003; 15:145–154Google Scholar

35 . Hughes JR: A review of the usefulness of the standard EEG in psychiatry. Clin Electroencephalogr 1996; 27:35–39Google Scholar

36 . Weilburg JB, Schachter S, Worth J, et al: EEG abnormalities in patients with atypical panic attacks. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:358–362Google Scholar

37 . Stevens JR, Bigelow L, Denney D, et al: Telemetered EEG-EOG during psychotic behaviors of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 36:251–262Google Scholar

38 . Small JG: Psychiatric disorders and EEG, in Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields. Edited by Niedermeyer E, Lopes da Silva F. Baltimore, Williams &Wilkins, 1993, pp 581–596Google Scholar

39 . Davis P: Electroencephalograms of manic-depressive patients. Am J Psychiatry 1941; 98:430–433Google Scholar

40 . Cook BL, Shukla S, Hoff AL: EEG abnormalities in bipolar affective disorder. J Affect Disord 1986; 11:147–149Google Scholar

41 . McElroy SL, Keck PR Jr, Pope HG Jr: Valproate in the treatment of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1988; 8:275–279Google Scholar

42 . Flor-Henry P: Ictal and interictal psychiatric manifestations in epilepsy: specific or nonspecific? Epilepsia 1972; 13:773–783Google Scholar

43 . Flor-Henry P: Psychiatric aspects of cerebral lateralization. Psychiatr Ann 1985; 15:429–434Google Scholar

44 . Levy AB, Drake ME, Shy KE: EEG evidence of epileptiform paroxysms in rapid cycling bipolar patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1988; 49:232–234Google Scholar

45 . Denny-Brown D: Brain trauma and concussion. Arch Neurol 1961; 5:1–3Google Scholar

46 . Reuber M, Fernandez G, Bauer J, et al: Interictal EEG abnormalities in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia 2002; 43:1013–1020Google Scholar

47 . Standage KF: The etiology of hysterical seizures. Can Psychiatr Assoc J 1975; 20:67–73Google Scholar

48 . King DW, Gallagher BB, Murvin AJ, et al: Pseudoseizures: diagnostic evaluation. Neurology 1982; 32:18–23Google Scholar

49 . Luther JS, McNamara JO, Carwile S, et al: Pseudoepileptic seizures: methods and video analysis to aid diagnosis. Ann Neurol 1982; 12:458–462Google Scholar

50 . Cohen RJ, Suter C: Hysterical seizures: suggestion as a provocative EEG test. Ann Neurol 1982; 11:391–395Google Scholar

51 . Wilkus RJ, Dodrill CB, Thompson PM: Intensive EEG monitoring and psychological studies of patients with pseudoepileptic seizures. Epilepsia 1984; 25:100–107Google Scholar

52 . Wilkes RJ, Thompson PM, Vossler DG: Bizzare ictal automatisms: frontal lobe epieleptic or psychogenic seizures. J Epilepsy 1990; 3:297–313Google Scholar

53 . Lelliott PT, Fenwick P: Cerebral pathology in pseudoseizures. Acta Neurol Scand 1991; 83:129–132Google Scholar

54 . Bowman ES: Etiology and clinical course of pseudoseizures: relationship to trauma, depression, and dissociation. Psychosomatics 1993; 34:333–342Google Scholar

55 . Devinsky O, Sanchez-Villasenor F, Vazquez B, et al: Clinical profile of patients with epileptic and nonepileptic seizures. Neurology 1996; 46:1530–1533Google Scholar

56 . Westbrook LE, Devinsky O, Geocadin R: Nonepileptic seizures after head injury. Epilepsia 1998; 39:978–982Google Scholar

57 . Pakalnis A, Paolicchi J: Psychogenic seizures after head injury in children. J Child Neurol 2000; 15:78–80Google Scholar

58 . Reuber M, Fernandez G, Helmstaedter C, et al: Evidence of brain abnormality in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav 2002; 3:249–254Google Scholar

59 . Teicher MH, Andersen SL, Polcari A, et al: The neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2003; 27:33–44Google Scholar

60 . Teicher MH, Dumont NL, Ito Y, et al: Childhood neglect is associated with reduced corpus callosum area. Biol Psychiatry 2004; 56:80–85Google Scholar

61 . Ito Y, Teicher MH, Glod CA, et al: Increased prevalence of electrophysiological abnormalities in children with psychological, physical, and sexual abuse. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1993; 5:401–408Google Scholar

62 . Teicher MH, Ito Y, Glod CA, et al: Preliminary evidence for abnormal cortical development in physically and sexually abused children using EEG coherence and MRI. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1997; 821:160–175Google Scholar

63 . Ito Y, Teicher MH, Glod CA, et al: Preliminary evidence for aberrant cortical development in abused children: a quantitative EEG study. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 10:298–307Google Scholar

64 . Davies RK: Incest: some neuropsychiatric findings. Int J Psychiatry Med 1979; 9:117–121Google Scholar

65 . Small JG, Milstein V, DeMyer MK, et al: Electroencephalographic (EEG) and clinical studies of early infantile autism. Clin Electroencephalogr 1977; 8:27–35Google Scholar

66 . Kim HL, Donnelly JH, Tournay AE, et al: Absence of seizures despite high prevalence of epileptiform EEG abnormalities in children with autism monitored in a tertiary care center. Epilepsia 2006; 47:394–398Google Scholar

67 . Tuchman R, Rapin I, Shinnar S: Autistic and dysphasic children, II: epilepsy. Pediatrics 1991; 6:1219–1225Google Scholar

68 . Villalobos R, Tuchman R, Jayakar P, et al: Prolonged EEG monitoring findings in children with pervasive developmental disorder and regression. Ann Neurol 1996; 40:300Google Scholar

69 . Tuchman R, Jayakar P, Yaylali I, et al: Seizures and EEG findings in children with autism spectrum disorders. CNS Spect 1997; 3:61–70Google Scholar

70 . Tuchman R, Rapin I: Epilepsy in autism. Lancet Neurol 2002; 1:352–358Google Scholar

71 . Gabis L, Pomeroy J, Andriola MR: Autism and epilepsy: cause, consequence, or coincidence. Epilepsy Behav 2005; 7:652–656Google Scholar

72 . Hughes JR, Melyn M: EEG and seizures in autistic children and adolescents: further findings with therapeutic implications. Clin EEG Neurosci 2005; 36:15–20Google Scholar

73 . Canitano R, Luchetti A, Zappella M: Epilepsy, electroencephalographic abnormalities, and regression in children with autism. J Child Neurol 2005; 20:27–31Google Scholar

74 . Chez MG, Chang M, Krasne V, et al: Frequency of epileptiform EEG abnormalities in a sequential screening of autistic patients with no known clinical epilepsy from 1996 to 2005. Epilepsy Behav 2006; 8:276–271Google Scholar

75 . Boutros NN, Fristad M, Abdollohian A: The 14 and 6 positive spikes and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 44:298–301Google Scholar

76 . Hughes JR, DeLeo AJ, Melyn MA: The EEG in attention deficit-hyperkinetic disorder: emphasis on epileptiform discharges. Epilepsy Behav 2000; 1:271–277Google Scholar

77 . Hemmer SA, Pasternak JF, Zecker SG: Stimulant therapy and seizure risk in children with ADHD. Pediatr Neurol 2001; 24:99–102Google Scholar

78 . Richer LP, Shevell MI, Rosenblatt BR: Epileptiform abnormalities in children with attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder. Pediatr Neurol 2002; 26:125–129Google Scholar

79 . Holtmann M, Becker K, Kentner-Figura B, et al: Increased frequency of rolandic spikes in ADHD children. Epilepsia 2003; 44:1241–1244Google Scholar

80 . Binnie CD, Marston D: Cognitive correlates of interictal discharges. Epilepsia 1991; 33(S6):S11–S17Google Scholar

81 . Aarts JH, Binnie CD, Smit AM, et al: Selective cognitive impairment during focal and generalized epileptiform EEG activity. Brain 1984; 107:293–308Google Scholar

82 . Marston D, Besag F, Binnie CD, et al: Effects of transitory cognitive impairment on psychosocial functioning of children with epilepsy: a therapeutic trial. Dev Med Child Neurol 1993; 35:574–581Google Scholar

83 . Massa R, de Saint-Martin A, Carcangiu R, et al: EEG criteria predictive of complicated evolution in idiopathic rolandic epilepsy. Neurology 2001; 57:1071–1079Google Scholar

84 . Engler F, Maeder-Ingvar M, Roulet E: Treatment with sulthiame (Ospolot) in benign partial epilepsy of childhood and related syndromes: an open clinical and EEG study. Neuropediatrics 2003; 34:105–109Google Scholar

85 . Duane DD, Heimburger G, Duane DC: Cognitive, behavioral and EEG effects of levetiracetam in pediatric developmental disorders of attention/learning. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2004; 16:218–241Google Scholar

86 . Deonna T, Roulet E: Autistic spectrum disorder: evaluating a possible contributing or causal role of epilepsy. Epilepsia 2006; 47(S2):79–82Google Scholar

87 . Stephani U, Carlsson G: The spectrum of BCECTS to LKS: the Rolandic EEG trait-impact on cognition. Epilepsia 2006; 47(suppl 2):67–70Google Scholar

88 . Mucci A, Volpe U, Meriotti E, et al: Pharmaco-EEG in psychiatry. Clin EEG Neurosci 2006; 37:81–98Google Scholar

89 . Binnie CD: Cognitive impairment during epileptiform discharges: is it ever justifiable to treat the EEG? Lancet Neurol 2003; 2:725–730Google Scholar

90 . Stevens JR: All that spikes is not fits: opus two, sunlight and the third eye. Presidential address to American Electroencephalographic Society, 1974Google Scholar