Phenomenology of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder in Patients with Temporal Lobe Epilepsy or Tourette Syndrome

METHOD

Patients with a diagnosis of OCD and temporal lobe epilepsy or Tourette syndrome were recruited in two tertiary referral clinics, namely patients with temporal lobe epilepsy and OCD at the Neuropsychiatry Research Group, Amedeo Avogadro University, in Novara, Italy, in the context of a previous study aimed to investigate OCD in epilepsy, 7 while patients with Tourette syndrome and OCD were among sequential clinical attendees at the Tourette Syndrome Clinic, the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London. Our study focused on identifying shared and dissociable obsessive-compulsive features in two “neuroanatomically distinct” patient groups; we did not therefore recruit patients with primary OCD alone.

The diagnosis of epilepsy accorded to the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) criteria 8 while Tourette syndrome and OCD accorded to DSM-IV-TR. Mental status examination, neurological examination, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computerized tomography (CT) scans were conducted. Patients younger than 18 years of age, with a reading level less than 6th grade, with learning disabilities or a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score <24 were excluded. After explanation of the procedures, patients gave informed consent.

All subjects were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Version (SCID-P), Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Y1 and Y2, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and the Structured Clinical Interview for Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Self-Report, Lifetime Version (SCI-OBS-SR). 9 All questionnaires were administered in a standardized way and in the same sequence.

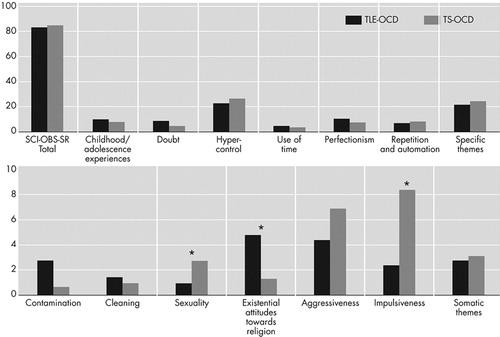

The Structured Clinical Interview for Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Self-Report consists of 183 items grouped into seven domains: childhood/adolescence experiences, doubt, hypercontrol, attitude toward time, perfectionism, repetition and automation, and specific themes. The last domain consists of 52 items and comprises a checklist of obsessive-compulsive traits and symptoms covering seven areas: contamination, cleaning, sexuality, existential attitudes toward religion, aggressiveness, impulsiveness, and somatic themes. We adopted the Structured Clinical Interview for Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Self-Report because we were interested in the specific psychopathological domains explored by this instrument. Moreover, it has several advantages including the lifetime interval, the time- and cost-effectiveness when compared with face-to-face interview, and its validation in both English and Italian, and the psychometric properties have been documented, showing an internal consistency between 0.61 and 0.90 and a test-retest and interrater reliability between 0.94 and 0.98. 9

The two groups were compared for age, gender, age at onset, duration of the disease, education level, marital status, psychiatric comorbidity, Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, BDI, and Structured Clinical Interview for Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Self-Report scores. The chi-squared analysis or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical data, while ordinal and linear data were assessed by nonparametric tests and one-way analysis of variance. Linear relationship was tested using the bivariate correlations procedure and two-tailed nonparametric measures as dictated by patient group size. Bonferroni’s correction was applied to account for the number of analyses, considering group differences and correlations statistically significant at p<0.002. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (Version 12 for Windows, SPSS Inc. Chicago).

RESULTS

Nine patients (4 males) with temporal lobe epilepsy and OCD, mean age 31.8 years (SD=6.6), and 15 patients (9 males) with Tourette syndrome and OCD, mean age 34.6 years (SD=10.1), were compared. There was no difference in gender, age, education level, and marital status. Neurological examination and neuroimaging investigations were normal in all patients. In the temporal lobe epilepsy group, five patients presented left-sided, two presented right-sided, and two presented bilateral EEG abnormalities.

Overall, psychiatric comorbidity was not different, with 50% of patients in both groups diagnosed with a mood disorder. However, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was significantly prevalent in Tourette syndrome. Thus, no patients with temporal lobe epilepsy and seven in the Tourette syndrome group fulfilled criteria for a diagnosis of ADHD, five of whom also had a comorbid mood disorder.

There was no group difference in partial and total Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale scores (TLE 12.8±4.6; TS 17.4±5.0), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Y1 (TLE 48.3±11.7; TS 50.0±11.6) and Y2 (TLE 55.6±10.2; TS 52.9±11.7), BDI (TLE 12.5±11.6; TS 11.4±8.1) and Structured Clinical Interview for Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Self-Report total scores (TLE 83.2±21.0; TS 84.8±17.4). However, there were significant between-group differences in the thematic content of obsessional symptoms ( Figure 1 ). In particular, temporal lobe epilepsy patients reported more obsessions relating to existential attitudes toward religion (TLE 4.8±2.6; TS 1.3±1.1; p<0.001), while the between-group difference relating to contamination cannot be considered statistically significant (TLE 2.8±2.2; TS 0.7±0.9; p=0.003). In contrast, obsessions relating to sexuality were more frequent in Tourette syndrome (TLE 1.0±0.7; TS 2.8±0.9; p<0.001), as was impulsiveness (TLE 2.4±1.4; TS 8.4±2.6; p<0.001).

*p<0.001

SCI-OBS-SR=Structured Clinical Interview for Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Self Report

In the temporal lobe epilepsy group, age significantly correlated with the Structured Clinical Interview for Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum domain “use of time” (r=0.904, p<0.001) and age at onset correlated with the domain “repetition and automation” (r=0.759, p=0.0018), yet there was no correlation between OCD severity, depression, and anxiety scores or specific OCD domains. In the Tourette syndrome group, there was no correlation between age at onset of the disease and Structured Clinical Interview for Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Self-Report domains, BDI, and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory scores. Age significantly correlated with sexual themes (r=0.599, p=0.0018), while Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale scores correlated with impulsiveness (r=0.792, p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

Early symptom subtyping approaches have characterized OCD patients by their principal compulsive behavior (e.g., checking or washing behaviors). Subsequent studies attempted to delineate latent structures within OCD symptoms. 10 – 11 In our study, we showed significant peculiarities in obsessive concerns and compulsions between the two groups. Thus, almost all Tourette syndrome patients referred to intrusive thoughts about scenes of sexual intercourse or unusual sexual activities, while compulsive behaviors included repetitive urge to masturbate, gamble, play with fire, provoke accidents, commit sexual violence, and aggressive behavior toward other people and objects. Although the high percentage of these symptoms in Tourette syndrome could be related to the inclusion of more males than females, there was no between-group difference in gender. Moreover, no patients fulfilled DSM criteria for impulse control disorders (e.g., kleptomania, pyromania, pathological gambling). Conversely, temporal lobe epilepsy patients referred to intrusive thoughts about aging, time passing and the need to atone for real or imaginary sins or mistakes (for example, by denying themselves food, a moment of relaxation, or something they like). We did not, however, observe a significant overrepresentation of contamination themes, although this may be more noticeable in larger temporal lobe epilepsy populations.

Interestingly, impulsiveness correlated with Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale scores only in Tourette syndrome. In fact, the presence of impulsivity seems to be a distinguishing feature in OCD with and without tics 12 and to be strictly interlinked with the symptom of feeling forced to touch that correlates with Tourette syndrome severity. 13 In temporal lobe epilepsy, OCD may also reflect salient aspects of the patients’ cognitive functioning due to the underlying neurological disorder, as suggested by the observed association between age and age at onset with the Structured Clinical Interview for Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum domains that explore obsessional slowness such as “use of time” or “repetition and automation.” Further research examining the neuropsychological features of OCD in epilepsy is clearly needed. Nevertheless, our results extend a literature suggesting a relationship between temporal lobe epilepsy and the development of specific personality characteristics, including obsessional traits and marked philosophical interests. 14

Similarities between the two groups should also be noted. Many clinical features are shared across core domains of OCD (i.e., indecision, checking behaviors, emotional control, conformity, and a tendency to precision, order, or symmetry). The two patient groups also shared associated emotional symptoms such as anxiety and depression levels. At a clinical level, the OCD in both groups often appeared to be egosyntonic (personally comfortable), rather than the egodystonic (subjectively uncomfortable) symptoms that characterize primary OCD. Egosyntonic OCD sometimes reflects comorbid personality disorder, but we do not have a formal assessment with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (SCID-II) to confirm this hypothesis. Conversely, the low Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale mean scores, especially in the temporal lobe epilepsy group, can be due to the treatment with antidepressants for the comorbid mood disorder that may have attenuated the psychopathological features of OCD. Finally, it is interesting that there was no difference in OCD traits during childhood, despite that Tourette syndrome and temporal lobe epilepsy have a different age of onset and time course.

The small sample size is a significant limitation for this study, influencing future replicability of the results. However, our report represents a proof of principal, suggesting that the underlying brain pathology, in terms of brain networks involved, may influence the formal content of obsessive concerns and compulsions.

1 . Insel TR: Toward a neuroanatomy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:739–744Google Scholar

2 . McKay D, Abramowitz JS, Calamari JE, et al: A clinical evaluation of obsessive-compulsive disorder subtypes: symptoms versus mechanisms. Clin Psychol Rev 2004; 24:283–313Google Scholar

3 . Berthier ML, Kulisevsky J, Gironell A, et al: Obsessive compulsive disorder associated with brain lesions: clinical phenomenology, cognitive function and anatomic correlates. Neurology 1996; 47:353–361Google Scholar

4 . Jenike MA: Theories of etiology, in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders: Practical Management, 3rd ed. Edited by Jenike MA, Baer L, Minichiello WE. St. Louis, Mo., Mosby, 1998, pp 203–221Google Scholar

5 . Robertson MM: Tourette syndrome, associated conditions and the complexities of treatment. Brain 2000; 123:425–462Google Scholar

6 . Isaacs KL, Philbeck JW, Barr WB, et al: Obsessive-compulsive symptoms in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2004; 5:569–574Google Scholar

7 . Monaco F, Cavanna A, Magli E, et al. Obsessionality, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2005; 7:491–496Google Scholar

8 . Commission on classification and terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy: Proposal for a revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Epilepsia 1989; 30:389–399Google Scholar

9 . Dell’Osso L, Rucci P, Cassano GB, et al: Measuring social anxiety and obsessive-compulsive spectra: comparison of interviews and self-report instruments. Compr Psychiatry 2002; 43:81–87Google Scholar

10 . Mataix-Cols D, Junque C, Sanchez-Turet M, et al: Neuropsychological functioning in a subclinical obsessive-compulsive sample. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 45:898–904Google Scholar

11 . Abramowitz JS, Franklin ME, Schwartz SA, et al: Symptom presentation and outcome of cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003; 71:1049–1057Google Scholar

12 . Hoehn-Saric R, Barksdale VC: Impulsiveness in obsessive-compulsive patients. Br J Psychiatry 1983; 143:177–182Google Scholar

13 . Robertson MM, Trimble MR, Lees AJ: The psychopathology of the Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 152:383–390Google Scholar

14 . Bear DM, Fedio P: Quantitative analysis of interictal behavior in temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Neurol 1977; 34:454–467Google Scholar