Psychosis in a Case of Schizophrenia and Parkinson’s Disease

To the Editor: The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia states that increased dopamine activity is the cause of the productive symptoms in schizophrenia. Parkinson’s disease in contrast is characterized by the loss of dopamine in the mesostriatal and mesolimbic system. Nuclear medicine provides two helpful methods in imaging the dopaminergic system: presynaptic dopamine transporter imaging with cocaine analogs (e.g., FP-CIT SPECT) and postsynaptic receptor imaging with D2 receptor ligands (e.g., IBZM SPECT). In idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, typically only presynaptic transporter function is impaired. Only a few case reports confirmed in vivo by FP-CIT SPECT that the coexistence of schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease can occur. 1 , 2 In addition to these reports we refer to treatment options of acute psychosis in schizophrenia and concomitant advanced Parkinson’s disease with motor fluctuations.

Case Report

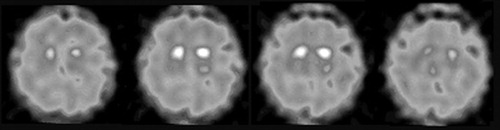

We report on a 74-year-old man with no dementia who was previously diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and repeatedly treated with first and second generation antipsychotics. Ten years ago parkinsonism was first described and antipsychotic treatment was switched to clozapine (62.5 mg/day). As the patient refused to take clozapine in the course of the disease it was replaced by olanzapine (5 mg/day). Additionally he received L -Dopa (400 mg/day) and pramipexole (4 mg/day) to treat parkinsonism. He responded well to treatment but later developed on/off-fluctuations and peak-dose dyskinesias, wherefore a treatment with amantadine (200 mg/day) was initiated. He then rapidly developed severe delusions. On admission we saw a psychotic patient who was disabled by severe on/off-fluctuation and peak-dose dyskinesias. As there was some doubt concerning the diagnosis of pure Parkinson’s disease, FP-CIT SPECT was performed and it showed bilaterally marked reduction of striatal dopamine transporter binding in the putamen ( Figure 1 ). Pramipexole and amantadine were stopped and quetiapine (125 mg/day) was added to the drug regimen, which led to marked improvement of the mental state. However, motor symptoms became worse. We increased the total dose of L -Dopa to 500 mg in combination with entacapone and shortened the intervals between the doses (five times 100 mg, every 3–4 hours) whereby good motor control was achieved.

There is some activity preserved in the caudate nucleus.

Discussion

FP-CIT SPECT allows differentiation between drug-induced parkinsonism and Parkinson’s disease. 3 As all antiparkinsonian agents can deteriorate the mental state, it seems useful to confirm the clinical diagnosis by means of a FP-CIT SPECT. There is an ongoing discussion about how extended medication contributes to the development of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. Some reviews recommend the reduction of antiparkinsonian drugs, 4 especially amantadine, anticholinergics, and dopamine agonists; others state that factors like dementia, age, or duration of disease contribute to the genesis of delusion and hallucinations. 5 In our case, the reduction of amantadine and pramipexole led to marked improvement of the delusions. This points to a relationship between medication and psychosis. We introduced quetiapine when the patient refused the clozapine treatment. We achieved good motor control by giving L -Dopa in shorter intervals and in combination with entacapone. This case illustrates the challenge of advanced Parkinson’s disease in chronic schizophrenia. If a coincidence of these two entities is suspected, we recommend differentiating between drug-induced parkinsonism and idiopathic Parkinson’s disease by presynaptic nuclear imaging.

1 . Schwarz J, Scherer J, Trenkwalder C, et al: Reduced striatal dopaminergic innervation shown by IPT and SPECT in patients under neuroleptic treatment: need for levodopa therapy? Psychiatry Res 1998; 83:23–28Google Scholar

2 . Winter C, Juckel G, Plotkin M, et al: Paranoid schizophrenia and idiopathic Parkinson’s disease do coexist: a challenge for clinicians. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006; 60:639Google Scholar

3 . Plotkin M, Amthauer H, Klaffke S, et al: Combined 123I-FP-CIT and 123I-IBZM SPECT for the diagnosis of parkinsonian syndromes: study on 72 patients. J Neural Transm 2005; 112:677–692Google Scholar

4 . Poewe W: Psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2003; 18:S80–7Google Scholar

5 . Merims D, Shabtai H, Korczyn AD, et al: Antiparkinsonian medication is not a risk factor for the development of hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm 2004; 111:1447–1453Google Scholar