Neuroanatomy of Pathological Laughing and Crying: A Report of the American Neuropsychiatric Association Committee on Research

The Clinical Phenotype

Emotional experience is the subjective feeling during an emotional event whereas emotional expression is the objective behavior that is expressed during such event, including changes in autonomic functions such as heart rate 1 , 2 and skeletal movements such as facial expression. Both the experience and the expression of an emotion are dependent in part upon the cognitive appraisal of the emotional stimuli which are triggering it, as reviewed extensively by others. 2 While many psychiatric conditions lead to a problem with emotional experience (e.g., mood disorders), many patients with neurological disorders suffer from problems with dysregulation of emotional expression . In these patients the problem involves mostly the expressions of laughter or crying. While some patients exhibit problems with only laughter, others have problems with only crying, and some exhibit problems with both. Although these patients do not laugh or cry at all times, when they do, the actual behavior of laughing or crying is often indistinguishable from normal acts of laughter and crying. Because the outbursts may occur in socially inappropriate times, this problem causes social handicap and suffering. In these patients, the actual motor behavior resembles normal laughing or crying behavior, so the problem of these patients is not simply in generating the motor act, as seen in patients with motor paresis or paralysis, or the flat affect encountered in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Insight is spared unless the affected patient’s awareness or consciousness is impaired. Most patients have accurate knowledge of cognitive, affective, and social norms of the moment and of the context in which their inappropriate emotional expression takes place. 3 Many of them are embarrassed by their inappropriate emotional display, which they cannot voluntarily prevent from happening or stop once it has occurred. The problem in these patients is clinically different than a mood disorder in which a pervasive and sustained change in emotional experience causes excessive but congruent emotional expression. Unlike mood disorders, inappropriate emotional expression in these patients is not a sustained phenomenon but a paroxysmal and episodic one. Moreover, the clinical phenotype, instead of being secondary to the problem of manic or depressive mood, is due to a dysregulated generation of an expression in the absence of a congruent or commensurate feeling. The clinical condition in our discussion is also a different entity than labile emotions seen in patients with personality disorders or in patients with emotional lability due to a general medical condition who change their emotional experience from extreme happiness to extreme sadness or vice versa. Again, the major distinguishing factor for the clinical phenotype in our discussion is the disassociation between emotional experience and expression. In some patients the expression of laughter or crying is incongruent with, or even contradictory to, the mood of the patient and to the emotional valence of the provoking stimulus, or is elicited chaotically without any trigger or by a stimulus without a clear emotional valence. Some may even switch from one expression to another in the setting of the same triggering stimulus. In other patients, emotional expression may not be absolutely incongruent with the mood of the patient or the valence of the triggering stimulus. However, the emotional expression of laughing or crying is “pathologically” exaggerated in intensity and frequency compared with the patient’s premorbid baseline. For example, a patient who never used to cry develops frequent weeping episodes that are excessive and exaggerated to the context in which they occur.

In summary, the clinical condition is about generating an emotional expression that is contextually inappropriate either because it is without any congruent or commensurate feeling, or because it is excessively exaggerated compared to the patient’s premorbid baseline. In either case, the condition is pathological because outbursts of contextually inappropriate laughing or crying cause social handicap and suffering for patients or their caretakers.

Terminology

The clinical condition has been known by different names, but the most widely used terms are “pseudobulbar affect,” “emotional lability,” “emotional incontinence,” and “pathological laughter and crying” or “pathological laughing and crying.” 4 Recently, a group proposed the further term of “involuntary emotional expression disorder” or IEED. 5 The terminology of this clinical condition has been confusing. 6 Different terms have been used to describe the same clinical presentation or similar terms are used for clinically different conditions. 6 In addition, some of these terms have their own inherent problems, 7 a discussion of which is beyond the scope of this report.

The aim of this report is not to focus on the problem of nosology. Instead, the primary aim of this review is to provide an in-depth analysis of the neuroanatomy of lesions leading to disassociation of emotional expression from emotional experience. Toward this aim, we will focus on clinical expressions where every clinician can argue beyond a reasonable doubt that there is a pathological problem with emotional expression that is not due to an underlying mood or personality disorder. Therefore, we will focus on cases in which there is a clear incongruence between the experienced and expressed emotion. In these cases, the term pathological laughing (or laughter) and crying (PLC) has been favored historically in the literature. 4 , 8 , 9

Neurological Disorders Causing PLC

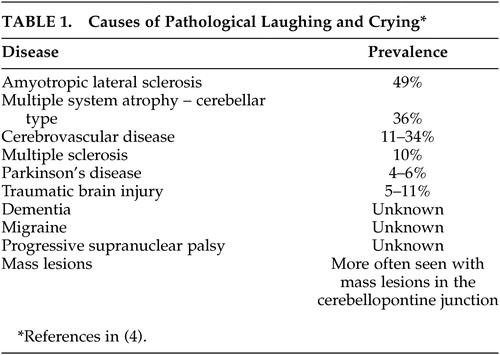

The precise prevalence of PLC in various neurological disorders is difficult to determine given the nosological problem discussed above. In addition, many of the studies of PLC did not use any specific diagnostic criteria and, in each study, the scope of the problem has been largely estimated in a small sample of cases. Thus the prevalence of PLC in various neurological disorders is largely based on limited and sketchy data ( Table 1 ). These limitations aside, the problem of PLC has been encountered in varying frequency and severity in patients suffering from stroke, 3 , 9 – 15 traumatic brain injury, 16 , 17 multiple sclerosis, 18 – 20 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, 21 – 23 brain tumor, 10 , 24 – 27 central pontine myelinolysis, 28 Parkinson’s disease, 29 and the cerebellar type of multiple system atrophy. 30 The scope of the problem in dementia is obscured by assessment differences among studies. In one report, the authors defined the problem as simply “observable sudden changes in emotional expressions” 31 and observed it in about 74% of mildly to moderately impaired patients with Alzheimer’s disease. In contrast, Starkstein and colleagues 32 used the Pathological Laughing and Crying Scale (PLACS) in their study of 103 patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Of these patients, 40 had problems with laughing and crying. However, it is noteworthy that 21 of these 40 patients also had an underlying congruent mood disorder. The authors labeled these patients as having “emotional lability,” which they defined as “pathological laughing and crying with an underlying mood disorder,” not specifying whether the seemingly labile episodes of emotional expression were secondary to an underlying lability of emotional experience.

|

Localization of Lesions in PLC

Most disorders in which PLC has been reported cause widespread damage to the cortical mantle or the subcortical white matter. Thus a clear correlation between the location of a lesion and the clinical phenotype may not be easily established. However, in some unique instances, small lesions confined to specific brain regions have been described. A systematic study of the location of such lesions will help us toward a better understanding of the pathophysiological mechanism(s) underlying this clinical condition. In the following text, we will review the evidence from classical and modern lesion studies. It should be noted that in many of these studies, the clinical condition was either defined vaguely or according to diagnostic criteria that would not have satisfied the current criteria. In the review of a given study, we will highlight this problem when applicable.

Classical Evidence: Prior to Neuroimaging Era

Oppenheim and Siemerling 33 in 1886 described cases of exaggerated emotional behavior in patients with lesions along the descending pathways to the brainstem. Oppenheim 34 coined the term “pseudobulbar affect” as “spasmodic explosive bursts of laughter or weeping” and concluded that lesions causing the problem rarely occupy the motor cortices. Instead, he stated that as a rule, they are situated in the subcortical white matter—especially corresponding to the posterior portions of the frontal lobe—in the internal capsule, or the basal ganglia. Bechterew 35 suggested that PLC was caused by lesions in the thalamus. In contrast, Brissaud 36 , 37 suggested that the integrity of the thalamus was essential to the appearance of “spasmodic laughter or weeping” and that the causative lesion must be one involving the anterior limb of the internal capsule, which he called the faisceau psychique . In his publication about the PLC, Wilson 8 also concurred with Brissaud and argued that softening of the anterior limb of the left internal capsule is mostly notable in cases of PLC. He suggested that the lesions must involve corticopontine, corticobulbar, and corticospinal tracts originating from the frontal operculum and lower end of the precentral gyrus, which descend through the anterior limb of the internal capsule. In 1903, Charles Fere 38 described fou rire prodromique , defined as an explosive and continuous laughter without a congruent emotional component due to an apoplectic event. Later autopsy studies of similar cases with fou rire prodromique revealed softening of the right lenticular nucleus and posterior capsule and degeneration of the anterior capsule, or bilateral pontine, caudate, and internal capsule ischemia or bilateral thalamic hemorrhages with intraventricular extension. 39 – 41 In the 1950s, Redvers Ironside 11 reported cases of single brainstem gliomas in the cerebellopontine angle and studied patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) who had developed PLC, which he defined as involuntary, spasmodic, uncontrollable, and prolonged attacks, superficially resembling the motor manifestations of natural laughter or crying that occur without the appropriate emotional feeling. Based on post-mortem analysis (in an unknown number of patients), he concluded that “pathological laughter disorder is most frequent in disease of both hemispheres interfering with cortico-hypothalamic and corticobulbar tracts controlling faciorespiratory mechanisms.” Poeck and Pilleri, 42 from a summary of the findings of 30 cases verified at autopsy in the literature, concluded that single circumscribed cortical lesions were not sufficient to cause PLC, which they defined as episodes of laughter or crying without association with the patient’s feelings. In contrast, subcortical lesions in the anterior limb of the internal capsule were reported in all 30 cases. The thalamus was only involved in two cases, and the hypothalamus, the red nuclei, and the substantia nigra remained intact in all cases. In a review of literature, Poeck 3 , 9 found an additional 22 cases of PLC in all of which the anterior limb of the internal capsule was reportedly damaged.

It should be noted that, prior to the neuroimaging era, brain lesions were primarily studied with the autopsy method, which may be limited in its spatial resolution. For instance, the microscopical analysis is performed on samples taken randomly from a few sites in the brain, and a comprehensive image of the CNS is thus unattainable. The brain is often dissected into 1–2 cm serial slices, and therefore small lesions often go undetected. Given this poor spatial resolution, even if a larger lesion is detected it will remain unclear if other lesions have been missed. In addition, a lesion seen on an autopsy specimen may or may not correlate in time with the onset of the clinical phenotype. Thus a causal relationship between a lesion and the clinical phenotype may remain hypothetical. Therefore, it is safe to state that the method of localizing lesions prior to the advent of modern neuroimaging methods was severely limited and the conclusions made in those studies must be taken with caution.

Modern Evidence: In the Neuroimaging Era

Since the invention of CT or MRI, a large number of studies aimed at establishing pathoanatomical correlations have been performed in patients with identifiable lesions. Although most of these cases are from patients with stroke or mass lesions, a few exceptional studies have also been reported in cases of demyelinating or neurodegenerative disorders.

Stroke

Kim and colleagues 43 reported a prospective study of 148 patients who visited the outpatient clinic because of poststroke “behavioral symptoms.” Kim and colleagues asked the patients or their relatives if the patient had shown “excessive or inappropriate laughing.” If either the patient or the relative confirmed more than two occasions of excessive or inappropriate laughing, the authors scored them as having “emotional incontinence.” The location of the lesions was detected by CT or MRI. This study revealed that poststroke “emotional incontinence” occurred more frequently after stroke in the lenticulocapsular region, basis pontis, medulla oblongata, or the cerebellum. As noted earlier in studies of pathological laughing and crying, the definition of the problem often suffers from vague measures and that it is often defined significantly differently across different studies. For instance, in a similar study by House and colleagues 44 in 1989, the problem of “emotionalism” was defined based on three questions: have you been more tearful; does the crying come suddenly at times when you are not expecting it; if you feel that tears are coming on, and if they have started, can you control yourself to stop them? From their report, it is unclear how the authors distinguished significant from nonsignificant “emotionalism.” They studied the site of ischemic infarcts on head CT scans obtained from 128 patients with first-time stroke. They found “emotionalism” in 15% at 1 month, in 21% at 6 months, and in 11% of patients at 12 months. Patients with “emotionalism” had larger lesions and significantly higher scores on measures of mood disorders, psychiatric problems, and intellectual deterioration. 44 Andersen and colleagues, 45 in a short communication, reported “pathological crying” defined as a “condition in which episodes occur in response to minor stimuli without associated mood changes” in 12 patients with stroke. Of these patients, only four had isolated brainstem lesions whereas the others had brainstem and large hemispheric lesions (n=4) or no brainstem lesion at all (n=4). One of the patients had an isolated cerebellar lesion. Among the four patients with isolated brainstem lesions, one had a large (>2 ml) lesion in the pons, another had a medium size (1–2 ml) lesion (location in the brainstem unclear), and the last two had only small (<1 ml) lesions (location in the brainstem unclear). Although the authors allude to a ventral location within the basis pontis, lesion locations in these patients lacked clear descriptions, making pathoanatomical correlations inconclusive. The authors nevertheless conclude that the lesions must have damaged the serotonergic nuclei in part because the patients responded to serotonergic therapy. Of note, the serotonergic system is not located in the ventral pons. Rather it is located posteriorly in the core of brainstem tegmentum, lesions of which are often associated with coma. 46 Kataoka and colleagues 47 studied 49 patients with acute paramedian pontine infarcts and classified them into paramedian, paramedian-tegmental, and tegmental. “Pseudobulbar affect with pathological laughing” (details of diagnosis unknown) was seen only in patients with paramedian basilar infarct, whereas none of the tegmental lesions caused pathological laughing. Arif and colleagues 48 reported a patient with a large paramedian basis pontis lesion who developed “pathological laughing” triggered by swallowing liquids but not solids. In keeping with these findings, Gavrilescu and Kase 49 reported that PLC is often associated with infarcts limited to the medial, rather than the lateral, territory of the basilar artery. Similar results were obtained by Kim and colleagues 13 who studied 37 patients with acute infarcts involving the base of the pons. They reported four cases with “transient uncontrollable laughter or excessive crying followed by inappropriate smiling,” and in all four, the lesion was in the paramedian basis pontis region. Paramedian pontine infarcts are particularly important because a single lesion in this territory causes bilateral damage to neurons in the basis pontis and their projections to the cerebellum. Thus a single paramedian pontine lesion will cause bilateral and widespread compromise in the pontocerebellar system. Parvizi and colleagues 14 described the case of a patient with PLC (with a score of 20 on the Pathological Laughing and Crying Scale developed by Robinson et al. 15 ). This patient had cerebellar deficits in bedside testing and a significant impairment in aspects of executive functions as measured by the Tower of Hanoi task in formal neuropsychological testing. A high resolution MRI revealed five small lesions, the largest of which was 12 mm in diameter. These lesions affected the cerebellar white matter (three lesions) or the paramedian basis pontis (one lesion) where cerebrocerebellar pathways are relayed to the cerebellum. One small lesion (∼2 mm) was located in the left cerebral peduncle in its posteriolateral segment, at the site of descending tracts originating from the posterior quadrant of the brain to the brainstem. The patient was otherwise free of any other lesions in the frontoparietal or subcortical sites. Based on these observations, Parvizi and colleagues suggested that the problem of emotional dysregulation in their patient was due to the disruption of descending pathways from the brain (such as the frontal lobes) to the cerebellum through the basis pontis. Additional cases have confirmed the importance of basis pontis in PLC. Tei and Sakamoto 50 reported a case of a 69-year-old woman who presented with right hemiparesis accompanied by “pathological laughter” after an infarct in the basis pontis. Larner 51 described a case of “pathological crying” with basilar artery occlusion. Doorenbos and colleagues 52 reported a case of a 73-year-old right handed man with left basis pontis (and cerebellar) hemorrhage, who developed “forced involuntary laughter” whenever his left hand developed cerebellar intention tremor. For instance, each time he lifted his left arm, which then started shaking, the patient would exclaim “Oh, my!” or “here we go again” and would start laughing uncontrollably. Finally, Lauterbach and colleagues 53 reported a case of a 62-year-old woman with a small infarction in the thalamus who developed pathological laughter along with myoclonus, dysdiadochokinesia and dyscoordination, consistent with cerebellar outflow interruption.

Mass Lesions

In 1976, Achari and Colover 10 reported two patients with “pathological laughter,” in both of whom a single tumor had been imaged in the cerebellopontine angle. Pathological laughing disappeared in both patients after the tumor’s surgical removal. As reviewed by Hargrave and colleagues, 54 to date nearly 20 similar cases of PLC have been reported in the literature to be associated with cerebellopontine angle tumors. For instance, Shafqat and colleagues 27 described a case of PLC in a patient with an extra axial retroclival mass compressing the left more than the right basis pontis. Nadkarni and Goel 56 reported a case of a 48-year-old woman with pathological laughter caused by a trochlear neurinoma in the cerebellopontine angle pushing on the basis pontis and right middle cerebellar peduncle. Matsuoka and colleagues 26 reported a case of a 40-year-old man with a clival chordoma pushing on the basis pontis and pathological laughter. Pollack and colleagues 58 reported “pseudobulbar symptoms” in children after the resection of posterior fossa tumors. In 12 of 142 patients with similar surgeries, patients with “pseudobulbar symptoms” had a significantly increased incidence of bilateral edema within the cerebellar peduncles. Bhatjiwale and colleagues 24 reported the case of four patients with large trigeminal neurinomas compressing the basis pontis who presented with pathological laughter. Parvizi and Schiffer 59 reported a 70-year-old man with exaggerated cerebellar tremor in parallel with exaggerated crying, defined as crying episodes in situations that would not have normally caused him to cry. This patient’s brain MRI revealed a midline cerebellar cyst without any evidence of other pathology. This patient had impairment in tasks requiring sustained attention and working memory, and on learning tasks that involved interference and distraction. He was weak in sequencing and switching from one cognitive set or strategy to another. He was inclined toward mild perseveration and showed lowered self-control and disregard for details of instruction. Similar deficits have been reported in patients with cerebellar lesions. 60 Recently, Famularo and colleagues 61 reported a 53-year-old man who presented with “intense and uncoordinated laughter.” A mass consistent with ependymoma was found in the cerebellar vermis abutting the floor of the fourth ventricle, which upon resection resulted in resolving the patient’s symptoms. 61

Neurodegenerative or Demyelinating Disorders

Compared to single lesions seen in the cases of vascular and mass lesions, patients with demyelinating or neurodegenerative disorders may have widespread lesions in the brain, and establishing a pathoanatomical relationship in these afflicted patients may be difficult. However, a few exceptions are noteworthy. Okuda and colleagues 62 using brain MRIs reported the case of a 16-year-old girl with multiple sclerosis who presented with “pathological laughter” in the context of an acute bilateral lesion in the cerebral peduncles. In a retrospective chart review of 28 patients with cerebellar multiple system atrophy, Parvizi and colleagues 30 found a problem with pathological laughter, crying, or both in 10 patients. The problem was specified in the medical charts as pseudobulbar laughing or crying. All these cases had been examined with brain MRI, and the brain of one patient with PLC was examined postmortem in autopsy, showing pathological changes in the cerebellum, basis pontis, pontocerebellar fibers, inferior olivary nuclei, and the olivocerebellar fibers. There were no signs of degeneration in the corticobulbar or corticospinal tracts or serotonegric raphe nuclei. Ghaffar and colleagues 63 studied the brain MRIs in 14 multiple sclerosis patients with PLC and 14 without PLC. Their results suggested that patients with PLC had more lesions in the brainstem, inferior parietal, medial inferior frontal, and right medial superior frontal regions. 63

Summary

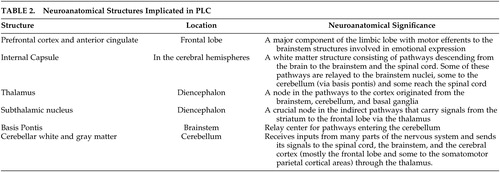

For the purpose of establishing a pathoanatomical correlation, the clinical phenotype must be clearly identified and detailed. As discussed earlier in the text, many of the studies reviewed above have defined the clinical phenotype of PLC in vague terms without specifying the details of their diagnostic criteria. Establishing a firm pathoanatomical conclusion on the basis of such evidence may therefore be limited. In spite of these limitations, the evidence reviewed above suggests strongly that the basis pontis stands out as the only identified site where a discrete lesion can cause PLC. Other anatomical sites that are often associated with PLC are internal capsule, cerebral peduncles, and the cerebellum. ( Table 2 )

|

What makes these structures important for the regulation of emotional expression? Is there additional evidence from functional and anatomical studies to support the role of these structures in regulation of emotional expression? Are these structures also part of the same network that is involved in emotional experience and its regulation (i.e., mood and feelings)? In the following text, we will review the current state of knowledge from functional studies to address these questions.

Neurophysiological Studies of Emotional Expression

Electrophysiological Stimulation Studies

Mirthful laughter, feelings of sadness, and a range of other emotional responses, have been elicited by electrical or mechanical stimulation of a variety of cortical and subcortical areas in humans. 64 – 69 However, the isolated motor components of laughing (without mirth) and crying (without sadness) characteristic of PLC have been produced by stimulation at only a few sites. 70 – 77 Okun and collegues 70 reported uncontrollable crying without sadness in a patient after deep brain stimulation of the left subthalamic nucleus (STN) for Parkinson’s disease. It is important to note that this patient had a left pallidotomy 8 years prior to the insertion of the ipsilateral STN electrode. Also noteworthy is the fact that the stimulation was performed through monopolar electrodes with possibility of current spread to the adjacent structures such as the white matter in the internal capsule. Stimulation through any of four electrode channels within the left STN produced uncontrollable crying. The authors specify that the crying episodes in this patient occurred without any congruent changes in her mood. They also specify that stimulations in the most ventral channel induced subjective feelings of anxiety and panic as if “she was somewhere she did not want to be.” The patient had a history of depression but was untreated during the STN surgery and a preoperative screening did not reveal any signs of depression or anxiety. The patient’s uncontrollable crying episodes were treated with sertraline (50 mg orally) and after 24–48 hours of treatment, there was marked improvement of crying. According to the authors, “two year follow up revealed that when the patient discontinued the sertraline for 1 week, she experienced crying episodes, fatigue, and felt “more off.” After therapy was reinstituted she improved in 24–48 hours.” Wojtecki and colleagues 71 reported the case of a 69-year-old patient with advanced Parkinson’s disease who developed frequent crying episodes in the absence of commensurate sadness more than 2 years after bilateral STN implantation. In a double-blind randomized manner, the patient was studied during several blocks of free conversations while the stimulator was switched on or off unbeknownst to the patient or the examiner. Interestingly, the patient exhibited seven episodes of crying during a total of 15 minutes of conversation blocks when the stimulator was on whereas no crying occurred when it was off. Moreover, in a semistandardized conversation with three emotional and neutral topics, the behavior of the patient was studied while monopolar stimulation was tested at each individual electrode contact. According to the authors, “crying occurred most frequently using ventral STN contacts and when the patient talked about emotional topics.” No details are available as to how the authors came to this conclusion. The patient was then examined using PET. Although no crying episodes occurred during the scanning, a comparison of stimulation ON with OFF conditions revealed a change of blood flow in the cerebellum, the thalamus, and the pons. When the ventral channel was turned on, there was lesser blood flow in the left cerebellum but higher blood flow to the thalamus compared to when the lateral contact was turned on or when there was no stimulation. Most recently, Low and colleagues 72 discovered pathological crying in a patient with advanced Parkinson’s disease and bilateral deep brain stimulators in the subthalamic nuclei when they stimulated in the region of the caudal internal capsule within ∼50Hz frequency range whereas a higher frequency resulted in a sensation of anxiety. A dominant view was that high frequency “stimulation” of the STN produces a functional inhibition. The current view is that the electrical fields generated through the STN electrodes change the dynamics of the rhythmic activity of STN neurons and affect the aberrant activity of some but not all STN neurons. Change of activity of STN neurons may also generate a diaschisis effect and disturb the neuronal activity of remote structures that are interconnected with the STN. Given that relatively high voltage is needed to induce laughing or crying with the STN stimulations, it is possible that the current spreads to other structures and/or fibers of passage outside the STN. However, Mallet et al. 75 argue on the basis of both physics and behavioral effects, that such current spread is limited to a distance on the order of one millimeter or less. Outside the STN territory, stimulation of the anterior cingulate has been known to cause changes in emotional expression without congruent change in the subject’s feelings. Sperli and colleagues 76 reported mirthless laughter evoked by stimulation of the right anterior cingulate cortex. Using either of two sets of bipolar electrode contacts, low current levels produced left lateralized smiling, which became bilateral and was followed by bilateral laughter as current levels were increased. Further increases in current levels produced corresponding increases in laughter duration and intensity. These same effects were replicated the following day. On neither day were the smiling and laughter accompanied by mirth, nor were there any effects of stimulation on the patient’s underlying mood. The authors characterize their study as the first in which cortical stimulation produced mirthless laughter. The discovery that anterior cingulate stimulation can produce mirthless laughter is of particular interest, since STN causes increased blood flow to the anterior cingulate (and lowers the blood flow to the putamen and fusiform gyrus) while the subjects view emotionally expressive faces compared to neutral faces. 77 Seizures deriving from hypothalamic hamartomas often are presaged by laughter (gelastic seizures) or crying (dacrystic seizures), or both, without accompanying mirth or sadness. Although the character of laughing or crying in these patients is sometimes reported to be different than normal laughing or crying, gelastic or dacrystic seizures provide important clues as to the neuroanatomy of emotional expression and its regulation. Kahane and colleagues 78 reported on five such patients (three gelastic, one dacrystic, one mixed). Depth electrode recordings from within the hamartoma revealed seizure activity confined to the tumor, with diffuse flattening of the cortical EEG during gelastic or dacrystic episodes. Electrical stimulation within the tumor of three patients produced the laughter or crying (again without mirth or sadness) seen during spontaneous seizure episodes or isolated laughing or crying attacks. In one patient, stimulation of the amygdala reproduced his usual gelastic seizures, but the seizures persisted following temporal lobectomy. The authors report additionally that subtle changes in cortical EEG activity were seen, apparently as secondary seizure phenomena, in several patients. The timing and topography of the changes suggested a spread of seizure activity from the hamartoma to the cortex, particularly left cingulate, bilateral cingulate, and orbito-cingulate areas. It was further noted that hypothalamic hamartomas tend to be tightly associated with the mamillary bodies, that lateralized hamartomas produce ipsilateral secondary cortical effects, and that ablation of the hamartoma (but not the cortex) abolishes both gelastic/dacrystic and secondary seizure activity.

In this text, we focused on the stimulation studies that have been shown to cause changes in emotional expression without causing congruent changes in the subjects’ mood or feeling. For this reason we did not review in detail studies that have shown simultaneous changes in emotional expression and experience. In summary, stimulation studies have suggested a possible role for the STN, anterior cingulate, and hypothalamic region in regulating emotional expression ( Table 2 ). It is important to note that the effect of stimulation in any one of these nodes may affect the activity of several other cortical or subcortical sites.

Functional Imaging Studies

Although there has been a surge of scientific inquiry about the neural basis of emotional experience and its regulation 79 – 85 there is little known about the neural correlates for pathological or normal regulation of emotional expression, and even fewer functional imaging studies have tackled the neuroanatomical correlates of pathological laughing or crying. In a brief report, Kosaka and colleagues 86 performed fMRI analysis on a patient with pathological laughing who had no demonstrated neurological lesions, psychiatric condition or apparent organic brain disorder (e.g., epilepsy, infarction or dementia) and presented with daily episodes of inappropriate and uncontrollable laughing not accompanied by a sense of joy or other pleasurable feeling. Three types of experimental tasks (i.e., sex discrimination, semantic discrimination, and finger-tapping) were performed with fMRI analysis to establish responses to nonspecific stimuli. The patient experienced a brief episode of laughing only during the sex discrimination task but higher pontine blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signals occurred during all three nonspecific stimulation tasks, while no such change was shown in control subjects. During the semantic tasks, increased BOLD signals in the pons were determined only in the patient while bilateral prefrontal, parietal, occipital cortices and the cerebellum had similar change in both the patient and controls. During the finger tapping task, increased pontine BOLD signals occurred only in the patient, while motor and temporal cortices, the supplemental motor area, and the cerebellum had increased BOLD signals in both the patient and control subjects. The control subjects showed no significant pontine response to any experimental task in intrasubject analysis. The patient was treated with paroxetine 10 mg daily for 2 weeks which was increased to 20 mg daily for the next 6 weeks. The laughing episodes gradually declined in frequency and disappeared after 6 weeks of treatment. After 8 weeks of treatment with paroxetine, a repeat fMRI study demonstrated that the patient’s abnormal pontine BOLD signals were no longer present. The significant change in the cerebellar blood flow also disappeared during the sex discrimination task but it continued during the other two tasks. This study implicates a change of activity in the pons during pathological laughing, which normalized after treatment with a serotonergic medication. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have as their primary mechanism of action blocking serotonin transporter proteins thereby preventing synaptic serotonin from being taken up into presynaptic terminals and allowing a greater opportunity for postsynaptic serotonin receptor binding and activity. Murai and colleagues, 87 using SPECT, examined upper brainstem and diencephalic serotonin transporter proteins density in six stroke patients with, and nine without, pathological crying. Patients were regarded as suffering from pathological crying when: (a) crying episodes were provoked more easily than in the prestroke period; (b) crying episodes were (at least sometimes) provoked suddenly for little or no reason; and (c) crying episodes were (at least sometimes) uncontrollable. The authors found that midbrain/pons serotonin transporter protein density was lower in the group with pathological crying. However, one patient in the pathological crying group was an outlier with an extremely low midbrain/pons binding ratio; after removal of data from this outlier there was no significant difference between the two groups. In this study, the authors used the method of voxel of interest method in which the examiner defined blobs of voxels of interest for midbrain/pons (3.3 cm 3 ) or the thalamus/hypothalamus (6.9 cm 3 ). Of note, voxels of interest for left or right cerebellar hemispheres (2.0 cm 3 ) were also chosen, but the cerebellar activity ipsilateral to the stroke side was used as a reference region in this study.

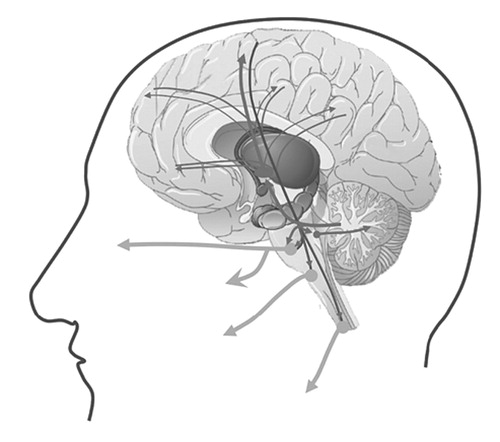

Proposed Pathophysiological Mechanisms

The cerebral cortex seems to be crucial for the cognitive appraisal of the contextual information of an emotional stimulus, and in any given situation, the intensity, frequency, and duration of the emotional response are adjusted according to this contextual information. Oppenheim and Siemerling 33 and Wilson 8 suggested that modulation is facilitated by direct corticobulbar pathways and in a linear top-down model. Their traditional view was coined at a time when the knowledge of brain anatomy and function was severely limited. According to their view, PLC occurs when the voluntary control of the emotional expression fails due to bilateral lesions of the descending corticobulbar tracts. In this view the primary problem in PLC is the problem of lack of voluntary control. In a recently proposed alternative hypothesis, 14 it was suggested that an intact relationship between the cerebral cortex and cerebellum is important for a normal regulation of emotional expression. In this view, the primary problem in PLC is the actual generation of a pathological response. According to this hypothesis, in normal individuals, the cerebellum modulates the profile of emotional response unconsciously and automatically according to the information it receives from the cerebral cortex regarding the cognitive and social context of the triggering stimulus, and that problems with exaggerated or contextually inappropriate emotional response result when the cerebellar modulation of these behaviors is impaired. 14 The resulting problem will then be an exaggerated response due to a lowered emotional threshold, or a wrong choice of response that is contextually inappropriate ( Figure 1 ).

Lesions that are known to be correlated with this clinical condition are often located in the frontal lobes, descending pathways to the brainstem, basis pontis, and the cerebellum. Possibly the ascending pathways through the thalamus and back to the frontal lobes might also be involved.

Figure is copyrighted. Permission is pending.

Treatment Options

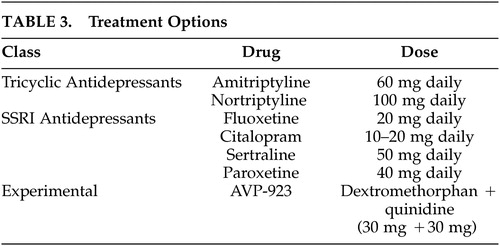

Agents that are effective for the treatment of mood disorders are also effective for the treatment of PLC- although the evidence suffers from two major limitations. First, the “level of evidence” seems to be confined to only case reports and clinical case series ( Table 3 ). Second, the clinical phenotype in some of these reports was not delineated in detail, and some of these studies were even performed without any firm diagnostic criteria or used confusing terminology. These limitations aside, these reports, suggest that tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline 88 and nortriptyline, 15 and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as sertraline, 89 paroxetine, 90 fluoxetine, 53 , 91 and citalopram 14 , 90 , 92 are effective in treating PLC. It is noteworthy that the beneficial effects of these medications in patients usually occur within days of treatment initiation and occur in response to doses less than those usually prescribed for the treatment of mood disorders. 93 Two recent clinical trials in patients with ALS and MS suggested that a compound consisting of dextrometorphan and quinidine may also be helpful in treating this condition. 94 , 95 The FDA approval of this compound is pending. If the drug is approved, head-to-head comparative clinical trials are needed to determine if the non-generic new compound will be superior in efficacy or side effect profile to the older generic treatment options. Of particular importance are observations that many patients with PLC also suffer from mood disorders. 4 One might argue that one should treat these patients with the medication that is known to have an effect on both mood problems and PLC rather than treating them with the new compound which not only may have no effect on the patients’ mood but also may cause undesirable interactions with the patients’ antidepressant medications, and cause financial burden on the affected patient. 96

|

Remaining Problems and Suggestions for Future Inquiries

In the text here we have summarized the current state of knowledge about the neuroanatomy of pathological laughing and crying in patients with neurological disorders. We will now highlight some of the most important gaps of knowledge about this condition that need to be addressed in the future inquiries.

Problem 1

Accurate estimates of the incidence and prevalence of pathological laughing and crying in the setting of specific neurological disorders are not available. Currently available data are limited because of the problem of small sample size. Future larger studies are needed to estimate the actual scope of the problem.

Problem 2

Do patients with pathological laughing and or crying have problems with dysregulation of other emotions such as anger or fear? Is the problem of pathological anger outburst or pathological fear related to the problem of pathological laughing and pathological crying? Diagnostic criteria defining these other emotional conditions need to be developed, and comorbidity studies undertaken in subjects with PLC.

Problem 3

Does the location of lesions correlate with the threshold of triggering laughter or crying episodes in patients with PLC? Does the frequency of these episodes and their type correlate with the location or the size of lesions? Epidemiological studies of triggering factors and large scale clinco-pathological studies will be needed to address these issues.

Problem 4

It is apparent that more imaging studies need to be performed on subjects exhibiting PLC in order to better identify specific brain networks involved. Although it is rare to capture an event during scanning, studies of baseline activity or during emotional processing will provide an invaluable tool.

Problem 5

The anatomical evidence suggests that the ventral pons, i.e., the basis pontis, is a crucial node in the circuitry that is affected in patients with PLC. Future inquiries are needed to determine how lesions in the basis pontis affect the activity of the cerebellum and the brainstem. If there is aberrant activity in the cerebellum, which region of the cerebellum is most involved, and how does that relate to aberrant activity elsewhere in the cerebral cortex or the brainstem tegmentum? Do lesions in the ventral basis pontis or elsewhere in the brain that cause PLC result in aberrant activity in the posterior region of the pons where the serotonergic raphe nuclei are located?

Problem 6

Laughter and crying are unique aspects of human behavior especially in social communication. Laughter and crying are also related in the sense that both use similar motor machineries. But why is it that some patients exhibit a lower threshold for only crying, whereas others have a problem with laughing only?

Problem 7

What neurotransmitters (other than serotonin) are involved in PLC? Is the compromise of such neurotransmitters global or specific to a certain brain region? Receptor binding and functional imaging studies using novel ligands may elucidate an understanding.

Problem 8

Some patients with PLC have mood congruent while others have mood incongruent emotional expressions. It remains to be determined if these represent only different scales of the same problem or different categories with different pathophysiological mechanisms. Do different variants of PLC correlate with dysfunction in different neuroanatomical systems?

Problem 9

Patients with epilepsy with or without hypothalamic hamartomas may manifest gelastic episodes of mirthless laughter or dacrystic episodes of crying without sadness. Some patients manifest both. Future neuroimaging and electrophysiological studies are needed to address the issue of seizure propagation, and functional and structural connectivity, in these patients.

Problem 10

It is remarkable that the problem of PLC is treated with medications that are known to have an effect of enhancing and stabilizing the mood (i.e., tricyclic antidepressants or serotonin reuptake inhibitors). This raises an interesting area for future research: what is the degree of overlap between the neural systems involved in regulating emotional expression and systems involved in regulating or perceiving emotional experience ?

1 . Levenson RW: Blood, sweat, and fears: the autonomic architecture of emotion. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003; 1000:348–366Google Scholar

2 . Gross JJ: Handbook of Emotional Regulation. New York; London, Guilford Press, 2007Google Scholar

3 . Poeck K: Pathophysiology of emotional disorders associated with brain damage, in Disorders of Higher Nervous Activity. Edited by Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW. Amsterdam, Elsevier, 1985, pp 343–367Google Scholar

4 . Parvizi J, Arciniegas DB, Bernardini GL, et al: Diagnosis and management of pathological laughter and crying. Mayo Clin Proc 2006; 81:1482–1486Google Scholar

5 . Cummings JL: Involuntary emotional expression disorder: definition, diagnosis, and measurement scales. CNS Spectr 2007; 12(suppl 5):Suppl-6Google Scholar

6 . Allman P: crying and laughing after brain damage: a confused nomenclature. J Neurol Neurosur Psychiatry 1989; 52:1439–1440Google Scholar

7 . Whitehouse PJ, Waller S: Involuntary emotional expressive disorder: a case for a deeper neuroethics. Neurotherapeutics 2007; 4:560–567Google Scholar

8 . Wilson SAK: Some problems in neurology. II: Pathological laughing and crying. J Neurol Psychopathol 1924; 4:299–333Google Scholar

9 . Poeck K: Pathological laughter and crying, in Clinical Neuropsychology. Edited by Frederiks JAM. Elsevier, 1985, pp 219–225Google Scholar

10 . Achari AN, Colover J: Posterior fossa tumors with pathological laughter. JAMA 1976; 235:1469–1471Google Scholar

11 . Ironside R: Disorders of laughter due to brain lesions. Brain 1956; 79:589–609Google Scholar

12 . Kim JS: Pathological laughter and crying in unilateral stroke. Stroke 1997; 28:2321Google Scholar

13 . Kim JS, Lee JH, Im JH, et al: Syndromes of pontine base infarction: a clinical-radiological correlation study. Stroke 1995; 26:950–955Google Scholar

14 . Parvizi J, Anderson SW, Martin C, et al: Pathological laughter and crying: a link to the cerebellum. Brain 2001; 124:1708–1719Google Scholar

15 . Robinson RG, Parikh RM, Lipsey JR, et al: Pathological laughing and crying following stroke: validation of a measurement scale and a double-blind treatment study. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:286–293Google Scholar

16 . Tateno A, Jorge RE, Robinson RG: Pathological laughing and crying following traumatic brain injury. J Neuropschiatr Clin Neurosci 2004; 16:426–434Google Scholar

17 . Zeilig G, Drubach DA, Katz-Zeilig M, et al: Pathological laughter and crying in patients with closed traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury 1996; 10:591–597Google Scholar

18 . Feinstein A, Feinstein K, Gray T, et al: Prevalence and neurobehavioral correlates of pathological laughing and crying in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 1997; 54:1116–1121Google Scholar

19 . Feinstein A, O’Connor P, Gray T, et al: Pathological laughing and crying in multiple sclerosis: a preliminary report suggesting a role for the prefrontal cortex. Mult Scler 1999; 5:69–73Google Scholar

20 . Minden SL, Schiffer RB: Affective disorders in multiple sclerosis: review and recommendations for clinical research. Arch Neurol 1990; 47:98–104Google Scholar

21 . Abrahams S, Goldstein LH, Al-Chalabi A, et al: Relation between cognitive dysfunction and pseudobulbar palsy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosur Psychiatry 1997; 62:464–472Google Scholar

22 . Gallagher JP: Pathologic laughter and crying in ALS: a search for their origin. Acta Neurol Scand 1989; 80:114–117Google Scholar

23 . McCullagh S, Moore M, Gawel M, et al: Pathological laughing and crying in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an association with prefrontal cognitive dysfunction. J Neurol Sci 1999; 169:43–48Google Scholar

24 . Bhatjiwale MG, Nadkarni TD, Desai KI, et al: Pathological laughter as a presenting symptom of massive trigeminal neuromas: report of four cases. Neurosurgery 2000; 47:469–471Google Scholar

25 . Lal AP, Chandy MJ: Pathological laughter and brain stem glioma [letter]. J Neurol Neurosur Psyshiatry 1992; 55:628–629Google Scholar

26 . Matsuoka S, Yokota A, Yasukouchi H, et al: Clival chordoma associated with pathological laughter. Case report [see comments]. J Neurosurg 1993; 79:428–433Google Scholar

27 . Shafqat S, Elkind MS, Chiocca EA, et al: Petroclival meningioma presenting with pathological laughter. Neurology 1998; 50:1918–1919Google Scholar

28 . van Hilten JJ, Buruma OJ, Kessing P, et al: Pathologic crying as a prominent behavioral manifestation of central pontine myelinolysis. Arch Neurol 1988; 45:936Google Scholar

29 . Siddiqui MS, Kirsch-Darrow L, Fernandez HH, et al: Prevalence of pseudobulbar affect in movement disorders and its mood correlates. Neurology 2006; 66:A369Google Scholar

30 . Parvizi J, Joseph J, Press DZ, et al: Pathological laughter and crying in patients with multiple system atrophy-cerebellar type. Mov Disord 2007; 22:798–803Google Scholar

31 . Haupt M: Emotional lability, intrusiveness, and catastrophic reactions. Int Psychogeriatr 1996; 8:3409–3414Google Scholar

32 . Starkstein SE, Migliorelli R, Teson A, et al: Prevalence and clinical correlates of pathological affective display in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosur Psychiatry 1995; 59:55–60Google Scholar

33 . Oppenheim H, Siemerling E: Mitteilungen uber Pseudobulbarparalyse und akute Bulbarparalyse. Berl kli Woch 1886; 46Google Scholar

34 . Oppenheim H: Textbook of Nervous Diseases for Physicians and Students by Professor H. Oppenheim of Berlin. English translation by Alexander Bruce. London, Edinburgh, T. N. Foulis Publisher, 1911Google Scholar

35 . Bechterew W: Die funktionen der Nervencentra. Jena, Fischer, 1909Google Scholar

36 . Brissaud E: Lecons sur les maladies nerveuses. Paris, Salpetriere, 1895Google Scholar

37 . Brissaud E: Sur le rire et le pleurer spasmodiques. Vingt-et-unième leçon, in Leçons sur les maladies nerveuses . Paris, Masson, 1895, pp 446–468 Google Scholar

38 . Féré MC: Le fou rire prodromique. Revue Neurologique 1903; 11353–11358Google Scholar

39 . Carel C, Albucher JF, Manelfe C, et al: Fou rire prodromique heralding a left internal carotid artery occlusion [comments]. Stroke 1997; 28:2081–2083Google Scholar

40 . Gondim FA, Thomas FP, Oliveira GR, et al: Fou rire prodromique and history of pathological laughter in the XIXth and XXth centuries. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2004; 160:277–283Google Scholar

41 . Wali GM: “Fou rire prodromique” heralding a brainstem stroke. J Neurol Neurosur Psyshiatry 1993; 56:209–210Google Scholar

42 . Poeck K, Pilleri G: Pathologisches lachen und weinen. Arch Neurol Psychiatr 1964; 92323–92370Google Scholar

43 . Kim JS, Choi-Kwon S: Poststroke depression and emotional incontinence: correlation with lesion location. Neurology 2000; 54:1805–1810Google Scholar

44 . House A, Dennis M, Molyneux A, et al: Emotionalism after stroke. Br Med J 1989; 298:991–994Google Scholar

45 . Andersen G, Ingeman-Nielsen M, Vestergaard K, et al: Pathoanatomic correlation between poststroke pathological crying and damage to brain areas involved in serotonergic neurotransmission [see comments]. Stroke 1994; 25:1050–1052Google Scholar

46 . Parvizi J, Damasio A: The neuroanatomical correlates of brainstem coma. Brain 2003; 1261524–1536Google Scholar

47 . Kataoka S, Hori A, Shirakawa T, et al: Paramedian pontine infarction. neurological/topographical correlation. Stroke 1997; 28:809–815Google Scholar

48 . Arif H, Mohr JP, Elkind MS: Stimulus-induced pathologic laughter due to basilar artery dissection. Neurology 2005; 64:2154–2155Google Scholar

49 . Gavrilescu T, Kase CS: Clinical stroke syndromes: clinical-anatomical correlations. [Review]. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev 1995; 7:218–239Google Scholar

50 . Tei H, Sakamoto Y: Pontine infarction due to basilar artery stenosis presenting as pathological laughter. Neuroradiology 1997; 39:190–191Google Scholar

51 . Larner AJ: Basilar artery occlusion associated with pathological crying: ‘folles larmes prodromiques’? Neurology 1998; 51:916–917Google Scholar

52 . Doorenbos DI, Haerer AF, Payment M, et al: Stimulus-specific pathologic laughter: a case report with discrete unilateral localization. Neurology 1993; 43:229–230Google Scholar

53 . Lauterbach EC, Price ST, Spears TE, et al: Serotonin responsive and nonresponsive diurnal depressive mood disorders and pathological affect in thalamic infarct associated with myoclonus and blepharospasm. Biol Psychiatry 1994; 35:488–490Google Scholar

54 . Hargrave DR, Mabbott DJ, Bouffet E: Pathological laughter and behavioural change in childhood pontine glioma. J Neurooncol 2006; 77:267–271Google Scholar

55 . Mouton P, Remy A, Cambon H: [Spasmodic laughter caused by unilateral involvement of the brain stem]. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1994; 150:302–303Google Scholar

56 . Nadkarni TD, Goel A: Trochlear nerve neurinoma presenting as pathological laughter. [Review]. Br J Neurosurgery 1999; 13:212–213Google Scholar

57 . Van Calenbergh F, Van de LA, Plets C, et al: Transient cerebellar mutism after posterior fossa surgery in children [comments]. [Review]. Neurosurgery 1995; 37:894–898Google Scholar

58 . Pollack IF, Polinko P, Albright AL, et al: Mutism and pseudobulbar symptoms after resection of posterior fossa tumors in children: incidence and pathophysiology. Neurosurgery 1995; 37:885–893Google Scholar

59 . Parvizi J, Schiffer R: Exaggerated crying and tremor with a cerebellar cyst. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2007; 19:187–190Google Scholar

60 . Schmahmann JD: Disorders of the cerebellum: ataxia, dysmetria of thought, and the cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2004; 16:367–378Google Scholar

61 . Famularo G, Corsi FM, Minisola G, et al: Cerebellar tumour presenting with pathological laughter and gelastic syncope. Eur J Neurol 2007; 14:940–943Google Scholar

62 . Okuda DT, Chyung AS, Chin CT, et al: Acute pathological laughter. Mov Disord 2005; 20:1389–1390Google Scholar

63 . Ghaffar O, Chamelian L, Feinstein A: Neuroanatomy of pseudobulbar affect: a quantitative MRI study in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2008; 255:406–412Google Scholar

64 . Bejjani BP, Damier P, Arnulf I, et al: Transient acute depression induced by high-frequency deep-brain stimulation [comments]. N Engl J Med 1999; 340:1476–1480Google Scholar

65 . Fried I, Wilson CL, MacDonald KA, et al: Electric current stimulates laughter [letter]. Nature 1998; 391:650Google Scholar

66 . Gordon B, Hart J Jr, Lesser RP, et al: Mapping cerebral sites for emotion and emotional expression with direct cortical electrical stimulation and seizure discharges. Prog Brain Res 1996; 107:617–622Google Scholar

67 . Lanteaume L, Khalfa S, Regis J, et al: Emotion induction after direct intracerebral stimulations of human amygdala. Cereb Cortex 2007; 17:1307–1313Google Scholar

68 . Meletti S, Tassi L, Mai R, et al: Emotions induced by intracerebral electrical stimulation of the temporal lobe. Epilepsia 2006; 47(suppl 5):47–51Google Scholar

69 . Meyer M, Baumann S, Wildgruber D, et al: How the brain laughs. Comparative evidence from behavioral, electrophysiological and neuroimaging studies in human and monkey. Behav Brain Res 2007; 182:245–260Google Scholar

70 . Okun MS, Raju DV, Walter BL, et al: Pseudobulbar crying induced by stimulation in the region of the subthalamic nucleus. J Neurol Neurosur Psychiatry 2004; 75:921–923Google Scholar

71 . Wojtecki L, Nickel J, Timmermann L, et al: Pathological crying induced by deep brain stimulation. Mov Disord 2007; 22:1314–1316Google Scholar

72 . Low HL, Sayer FT, Honey CR: Pathological crying caused by high-frequency stimulation in the region of the caudal internal capsule. Arch Neurol 2008; 65:264–266Google Scholar

73 . Benedetti F, Colloca L, Lanotte M, et al: Autonomic and emotional responses to open and hidden stimulations of the human subthalamic region. Brain Res Bull 2004; 63:203–211Google Scholar

74 . Krack P, Kumar R, Ardouin C, et al: Mirthful laughter induced by subthalamic nucleus stimulation. Mov Disord 2001; 16:867–875Google Scholar

75 . Mallet L, Schupbach M, N’Diaye K, et al: Stimulation of subterritories of the subthalamic nucleus reveals its role in the integration of the emotional and motor aspects of behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007; 104:10661–10666Google Scholar

76 . Sperli F, Spinelli L, Pollo C, et al: Contralateral smile and laughter, but no mirth, induced by electrical stimulation of the cingulate cortex. Epilepsia 2006; 47:440–443Google Scholar

77 . Geday J, Ostergaard K, Gjedde A: Stimulation of subthalamic nucleus inhibits emotional activation of fusiform gyrus. Neuroimage 2006; 33:706–714Google Scholar

78 . Kahane P, Ryvlin P, Hoffmann D, et al: From hypothalamic hamartoma to cortex: what can be learnt from depth recordings and stimulation? Epileptic Disord 2003; 5:205–217Google Scholar

79 . Ekman P: Facial expressions of emotion: an old controversy and new findings. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1992; 335:63–69Google Scholar

80 . de Gelder B: Towards the neurobiology of emotional body language. Nat Rev Neurosci 2006; 7:242–249Google Scholar

81 . Niedenthal PM: Embodying emotion. Science 2007; 316:1002–1005Google Scholar

82 . Panksepp J: Affective neuroscience: the foundations of human and animal emotions. New York, Oxford University Press, 1998Google Scholar

83 . Davidson RJ, Scherer KR, Goldsmith HH: Handbook of Affective Sciences. New York, Oxford University Press, 2003Google Scholar

84 . LeDoux JE: The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life. New York, Touchstone, 1998Google Scholar

85 . Damasio AR: Descartes’ Error. New York, Putnam, 1994Google Scholar

86 . Kosaka H, Omata N, Omori M, et al: Abnormal pontine activation in pathological laughing as shown by functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006; 77:1376–1380Google Scholar

87 . Murai T, Barthel H, Berrouschot J, et al: Neuroimaging of serotonin transporters in post-stroke pathological crying. Psychiatry Res 2003; 123:207–211Google Scholar

88 . Schiffer RB, Herndon RM, Rudick RA: Treatment of pathologic laughing and weeping with amitriptyline. N Engl J Med 1985; 312:1480–1482Google Scholar

89 . Burns A, Russell E, Stratton-Powell H, et al: Sertraline in stroke-associated lability of mood. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1999; 14:681–685Google Scholar

90 . Muller U, Murai T, Bauer-Wittmund T, et al: Paroxetine versus citalopram treatment of pathological crying after brain injury. Brain Inj 1999; 13:805–811Google Scholar

91 . Seliger GM, Hornstein A, Flax J, et al: Fluoxetine improves emotional incontinence. Brain Inj 1992; 6:267–270Google Scholar

92 . Andersen G, Vestergaard K, Riis JO: Citalopram for post-stroke pathological crying. Lancet 1993; 342:837–839Google Scholar

93 . Schiffer R, Pope LE: Review of pseudobulbar affect including a novel and potential therapy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005; 17:447–454Google Scholar

94 . Brooks BR, Thisted RA, Appel SH, et al: Treatment of pseudobulbar affect in ALS with dextromethorphan/quinidine: a randomized trial. Neurology 2004; 63:1364–1370Google Scholar

95 . Panitch HS, Thisted RA, Smith RA, et al: Randomized, controlled trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine for pseudobulbar affect in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2006; 59:780–787Google Scholar

96 . Johnston SC, Hauser SL: Marketing and drug costs: who is laughing and crying? Ann Neurol 2007; 61:11A–12AGoogle Scholar