Behavioral Neurology and Neuropsychiatry Fellowship Training: The Johns Hopkins Model

Neuropsychiatry can be seen as a mirror image that begins its focus from the “top down,” starting with productive syndromes that occur in overt brain disease (e.g., agitation, anxiety, mood disorders, psychosis) 1 and linking these to underlying brain disease. Neuropsychiatry also has a long history, although it had been overshadowed for much of the 20th century in the United States by more psychodynamic models that focused on idiopathic psychiatric disorders rather than on behavioral manifestations of neurological disease.

It has only been relatively recently that the commonalities of the two approaches have been widely appreciated. As an example, Alzheimer’s disease can cause agnosia, amnesia, aphasia, and apraxia (all traditionally studied in behavioral neurology), but also often involves agitation, depression, and psychosis (all traditionally studied in neuropsychiatry). 1 Indeed, most diseases that affect the brain are associated with deficiency (negative) as well as productive (positive) syndromes, ranging from multiple sclerosis to epilepsy to trau-matic brain injury to Parkinson’s disease. Rather than these being “neurological diseases” only, they may be thought of more comprehensively as “neuropsychiatric disorders,” particularly as the psychiatric and other behavioral aspects are sometimes more burdensome to patients than the motor or other “neurological” aspects. 2

Additionally, techniques such as neuroimaging and neuropsychological testing are commonly used by both behavioral neurologists and neuropsychiatrists. This, of course, is not surprising since both specialties focus on normal and abnormal brain functioning, and both specialties use a comprehensive approach to formulating diagnoses and treating patients that incorporates biological and environmental factors. Thus, both specialties focus on the same organ and on many of the same diseases and use many of the same tools. The appreciation of the commonalities in the two fields is not an entirely new development, as in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the neurological and psychiatric approaches to brain function were not thought to be so separate. Indeed, Freud was trained as a neurologist and Alzheimer as a psychiatrist. In many ways, then, the current appreciation of neuropsychiatric disorders and treatment approaches is an example of history being circular.

Fellowship Development

In appreciation of the commonalities of the two fields, Behavioral Neurology & Neuropsychiatry has recently been accredited as a unitary fellowship by the United Council for Neurologic Subspecialties (UCNS). 3 – 5 The UCNS has developed a specific curriculum and specific requirements for trainees in this fellowship. The curriculum is extensive and has the goal of training psychiatrists or neurologists who are knowledgeable about the range of behavioral manifestations of neurological disease. Training requirements include the development of expertise in the neurological exam and mental status exam, interpreting neuropsychological assessments, interpreting neuroimaging results, interpreting electrophysiologic testing, psychopharmacology, neuropsychiatric syndromes, and cognitive/emotional/behavioral manifestations of neurological disorders. 3

The UCNS certifies fellowship sites and does site visits. After fellowship training, the physician is then qualified to take the Behavioral Neurology & Neuropsychiatry board examination. The UCNS website has an updated list of accredited programs and information on the certification examination (www.ucns.org).

The goal of providing common training to both future behavioral neurologists and neuropsychiatrists is ambitious. Since the accredited fellowships just started during the 2005–2006 academic year, multiple difficulties in achieving this goal are likely. We describe in this report a specific model, at Johns Hopkins, to implement the goals of the Behavioral Neurology & Neuropsychiatry Fellowship.

Johns Hopkins: History in the Field

Johns Hopkins is uniquely poised to offer a model of this sort of training, as the institution has a long history of research and treatment of brain diseases. The program in neuropsychiatry has a long history at Johns Hopkins. Clinical and research activities in neuropsychiatry were initiated by Dr. Marshall Folstein in the 1970s under the mentorship of Dr. Paul McHugh. The geriatric service was founded and developed further by Dr. Peter Rabins in 1978. The neuropsychiatry service was founded by Dr. Constantine Lyketsos in 1993. The Division of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neuropsychiatry was founded in 2002 with the merger of the geriatric psychiatry and neuropsychiatry services.

The program in behavioral neurology also has a long history at Johns Hopkins. Clinical and research activities were initiated by Dr. Barry Gordon in the 1980s, with the founding of the cognitive neurology/neuropsychology group. The initial focus was on memory and language disorders. The faculty interested in cognitive neurology has steadily grown over time. The faculty now includes individuals with research interests in a wide variety of cognitive processes and disorders, including aging and Alzheimer’s disease, autism, cerebellar function, epilepsy, and vascular disease. The Division of Cognitive Neuroscience was established in 2003, in recognition of the expanding activities in this area.

As indicated above, both departments have a long history and tradition. In order to provide for this multidisciplinary fellowship, faculty in both departments had to look beyond traditional concerns about “turf” and cooperate. Before the current version of the fellowship was formulated, the fellowship was entirely housed administratively within the department of psychiatry. At Hopkins, the psychiatry department initiated the fellowship, but actively sought out cooperation from neurology faculty due to the inherently multidisciplinary nature of the fellowship.

The current fellowship is a combined effort by the departments of psychiatry and neurology. There are currently 21 faculty members affiliated with the fellowship. The fellowship director is board-certified in psychiatry and has done a fellowship in neuropsychiatry. The fellowship co-director is board-certified in neurology and has done fellowships in clinical neurophysiology and cognitive neurology. Faculty members from both departments treat and study the affective, behavioral, and cognitive symptoms of multiple brain diseases, including traumatic brain injury, 6 multiple sclerosis, 7 epilepsy, 8 , 9 stroke, 10 Huntington’s disease, 11 Parkinson’s disease, 12 Alzheimer’s disease, 13 frontotemporal dementia, 14 and restless leg syndrome. 15 Earlier faculty members made major contributions in the study of affective changes after stroke. 16 Indeed, Hopkins faculty have played a crucial role in guiding people caring for patients with Alzheimer’s or other types of dementia 17 and in delineating concepts of bedside cognitive testing such as the Mini-Mental State Examination, 18 poststroke depression, 16 depression in Alzheimer’s disease, 19 and the epidemiology of dementia. 20 Faculty are also influencing evolving concepts that cut across various brain diseases such as Involuntary Emotional Expression Disorder (IEED). 21 Additionally, Hopkins has invested significantly in infrastructure for the treatment and study of brain diseases, with a new interdisciplinary Memory Center opening at the Johns Hopkins Bayview campus in 2008.

With the history and current active environment in the study of neuropsychiatric symptoms, as well as cooperation across neurology and psychiatry departments, Hopkins is admittedly in a unique situation to provide training for a Behavioral Neurology & Neuropsychiatry Fellowship. Regardless, the Hopkins model might be emulated by others as the principles are generalizable.

The Hopkins Fellowship

The mission statement for the Hopkins fellowship is as follows:

The fellowship provides training and supervision in clinical and research activities in Behavioral Neurology and Neuropsychiatry, consistent with the guidelines established by the United Council for Neurological Subspecialties (UCNS). The aim of the fellowship is twofold: (1) to impart to the Behavioral Neurology and Neuropsychiatry fellows clinical competencies in the assessment and management of patients with neurologically based cognitive, behavioral and emotional problems; and (2) to provide basic understanding and competency to conduct clinical research in Behavioral Neurology and Neuropsychiatry.

Thus, fellows will be able to graduate from the program as clinician-scientists and will be in an excellent position to either join an academic setting (with clinical and research responsibilities in either psychiatry or neurology) or predominantly function as clinicians in a practice setting (affiliated with a neurology or a psychiatry practice).

The Hopkins fellowship program attempts to achieve the above mission by emphasizing exposure to multiple brain diseases that have affective, behavioral, perceptual, personality, or cognitive (including thought and language) components. In the first year, clinical rotations include specialized interdisciplinary clinics in the following conditions: epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease/movement disorders, Huntington’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, stroke, normal pressure hydrocephalus, neurodevelopmental disorders, traumatic brain injury, pain, and headache. In addition, there are rotations on an inpatient neuropsychiatry unit (a unit designed to treat the psychiatric and other behavioral aspects of brain disease) and a neurodevelopmental disorders unit. There are also rotations geared toward developing familiarity with neuroimaging and neuropsychology. Although rotations in neuroimaging and neuropsychology will by no means make the fellow an expert in those areas, the goal is to make the fellow able to appropriately order and interpret neuroimaging and neuropsychology reports.

The second year of the fellowship emphasizes research, including neuroimaging and clinical trials. While the fellows are introduced to research in the first year as they rotate in several clinics with research studies (such as Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and traumatic brain injury clinics), it is in the second year that the fellows spend a lot more time in a research clinic of their interest. The goal is to develop a study protocol and to submit a grant application by the end of the second year. Fellows have the opportunity to learn as needed specific research techniques that are relevant to their interests by collaborating with experts at Hopkins. For example, to learn about imaging biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease, the fellow would be able to work with a neuropsychiatrist in the department who specializes in this, as well as neuroradiologists who collaborate with the neuropsychiatrist. Besides specific techniques, general research methodology (including statistics) can be obtained through the close collaboration the fellowship program has with the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. The fellow has the opportunity to take research methodology/epidemiology courses with the School of Public Health. In addition, several neuropsychiatry faculty members have public health degrees and can guide the fellow on statistical/methodological issues.

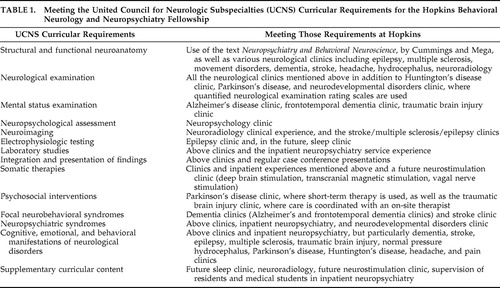

In this model, the emphasis is on exposure to a great variety of neurological diseases and techniques to help trainees develop common, evidence-based strategies to treat the affective, behavioral, and cognitive aspects of brain diseases regardless of what the disease is, as well as appreciate subtle differences in presentation and treatment between these diseases. Table 1 summarizes how the fellowship meets the UCNS training requirements.

|

Additionally, trainees are taught to think about neuropsychiatric cases in a holistic manner. Formulation of neuropsychiatric cases using the “Four Perspectives of Psychiatry” is emphasized. The Perspectives of Psychiatry, 22 developed by Johns Hopkins professors Drs. Paul McHugh and Phillip Slavney, provide an organized approach to diagnosis and treatment of patients with multiple medical and psychosocial problems. The four perspectives are: disease, dimensions, behavior, and life story.

Each perspective has a unique set of principles that explains neuropsychiatric disturbances and guides treatment in a very specific way. The perspective of disease explains affective, behavioral, or cognitive disturbances as a product of “broken parts” of the brain—be they molecular, cellular, or in functional systems. Treatment using the disease approach focuses on medication or surgical therapies to “cure” or minimize signs and symptoms. The perspective of dimensions focuses on a mismatch between a person’s vulnerabilities (cognitive and/or personality) and the demands of the environment. “Guidance and strength” to the patient and family help reduce distress and improve adaptation. The behavior perspective focuses on abnormal goal-directed behaviors and the role of learned or “shaped” factors such as destructive behaviors and the consequences that sustain these behaviors. Treatment includes “interpretation and conversion” of the behavior to acceptable and appropriate norms. The life story perspective is based on the logic of narrative and explains affective and behavioral problems as a result of disturbing life experiences leading to demoralization. “Rescripting” the person’s life helps restore morale and provides for a better understanding of the problems in the current context of their life.

Although the Perspectives of Psychiatry can be used to formulate diagnoses in patients with idiopathic psychiatric disorders, it is particularly helpful to explain and treat the numerous problems patients with brain injury present. This is best illustrated in a case report that was recently published regarding a middle-aged male with multiple traumatic brain injuries and several neuropsychiatric sequelae. 23 The four perspectives approach greatly helped in defining and treating his problems and helped him attain an optimal level of functioning. A purely biological approach, which is often used in patients with brain injury, tends to highlight the disease at the cost of the person

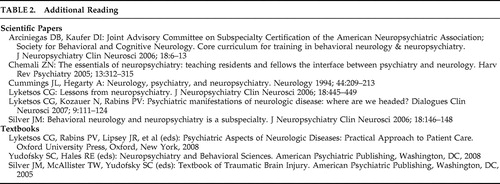

The fellowship also provides formal teaching, with didactic education provided by weekly seminars. Seminars include case presentations by fellows, critical reading of the literature (journal club), discussion of chapters in neuropsychiatric textbooks, and an introductory course on research provided by one of the faculty members. Faculty affiliated with the fellowship have written and edited a textbook of neuropsychiatry, 24 reflecting the depth of expertise the fellow has access to (and the vision that the fellowship has for neuropsychiatry as a field). The didactic topics the fellow is exposed to include principles of neuropsychiatry and the neuropsychiatric aspects of various diseases (including epilepsy, stroke, traumatic brain injury, and dementias). See Table 2 for a list of didactics. Other educational activities available include: weekly grand rounds, weekly research conferences, weekly genetics conferences, weekly residents journal clubs, and weekly neuropsychology seminars.

|

Additionally, the fellowship focuses on the mentor-trainee relationship, with mentors from both psychiatry and neurology. As there are a variety of faculty members in both departments who are willing to mentor, the fellow can choose various areas of study to focus on or learn about specific techniques. The fellowship director helps to coordinate this for the fellow. Besides the ability to find mentors to help in specialization, exposure to the intellectual climate in both departments allows the fellow to learn from faculty members who have successfully been able to attract grant funding and apply their findings to patient care.

Advantages of the Hopkins Model

The Hopkins fellowship has multiple components all designed to provide trainees a comprehensive overview of Behavioral Neurology & Neuropsychiatry. Significant emphasis is placed on exposure to multiple brain diseases, with the behavioral aspects highlighted as much as possible in several clinical settings, under the supervision of a range of teachers from both core disciplines. Exposure to various clinics also provides practice for training in neuropsychiatric evaluation (including the neurological exam), which is emphasized in the fellowship. Additionally, the fellow learns to appreciate that regardless of the specific disease, patients often have affective, behavioral, and cognitive symptoms that can be treated. The emphasis on a holistic approach to formulation ensures that the full complexity of neuropsychiatric symptoms and etiologies (i.e., the four perspectives) is appreciated. Additionally, the inpatient experiences, in combination with the outpatient clinics, provide the fellow with a range of symptom exposure, from mild to severe and acute to chronic.

The weekly didactics provide a way of learning from published literature, synthesizing data and outcomes via regular case presentations, and critically evaluating data. The didactics allow the fellow to have exposure to multiple opinions on patients from residents and faculty members. The education and mentoring provided by experts in the fields of both psychiatry and neurology add to the uniqueness of the program and provide an opportunity for both psychiatrists and neurologists to participate in training.

As the fellowship is new, we have had only one fellow graduate from our program so far (in 2007). We also currently have one fellow in training. Hence, there is limited data on the efficacy of the Hopkins model. However, by measures of research publications and current career status, our graduate is doing well. He was recruited to start a neuropsychiatry program (including an outpatient clinic, an inpatient consult service, and research projects) at an interdisciplinary neurosciences institute. He also has had publications to come out of his time in the fellowship. 23 , 25

CONCLUSION

This is an exciting time in the study of brain-behavior relationships. The approaches of behavioral neurology and neuropsychiatry have been combined in terms of training with a new joint fellowship supervised by the UCNS. Despite the excitement of bringing together to some extent the training of neurologists and psychiatrists, it is difficult to implement a model that can achieve this. Here, we have provided one model, used at Johns Hopkins (an institution with a strong history and active environment in the field), that emphasizes exposure to multiple brain diseases, techniques, perspectives, and faculty. The circuitry in the brain does not arbitrarily distinguish between a neurological and a psychiatric function and neither should practitioners. This fellowship has an opportunity to role model the need to relinquish this dichotomy.

This is not the only way such a fellowship might be constructed, and it remains to be seen if this is even the best approach. Any fellowship in this area must be flexible and willing to change; indeed, the Hopkins curriculum will hopefully be expanded in the future to include more exposure to electrophysiological testing, neurostimulation, sleep disorders, and brain tumor patients. At this stage, one might argue that the training of behavioral neurologists/neuropsychiatrists needs to be broad due to the inherent multidisciplinary nature of the field. In addition, however, the fellow must be able to be an expert in behavioral problems in many specific brain diseases. By focusing on the commonalities across different brain diseases as well as common tools (the neurological exam, neuroimaging, and neuropsychological testing), the fellow is provided with unique training, both broad and deep.

1. Cummings JL, Mega MS: Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience. New York, Oxford University Press, 2003Google Scholar

2. Kanner AM: Depression and epilepsy: a new perspective on two closely related disorders. Epilepsy Curr 2006; 6:141–146Google Scholar

3. Behavioral Neurology & Neuropsychiatry Requirements. United Council for Neurologic Subspecialties, St. Paul, Minn, 2006. Available at www.ucns.orgGoogle Scholar

4. Silver JM: Behavioral neurology and neuropsychiatry is a subspecialty. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006; 18:146–148Google Scholar

5. Arciniegas DB, Daniel I, Kaufer DI, Joint Advisory Committee on Subspecialty Certification of the American Neuropsychiatric Association, Society for Behavioral and Cognitive Neurology: Core curriculum for training in behavioral neurology and neuropsychiatry. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006; 18:6–13Google Scholar

6. Lee HB, Lyketsos CG, Rao V: Pharmacological management of the psychiatric aspects of traumatic brain injury. Int Rev Psychiatry 2003; 15:359–370Google Scholar

7. Pucak ML, Kaplin AI: Unkind cytokines: current evidence for the potential role of cytokines in immune-mediated depression. Int Rev Psychiatry 2005; 17:477–483Google Scholar

8. Marsh L, Rao V: Psychiatric complications in patients with epilepsy: a review. Epilepsy Res 2002; 49:11–33Google Scholar

9. Crone NE, Hao L, Hart J, et al: Electrocorticographic gamma activity during word production in spoken and sign language. Neurology 2001; 57:2045–2053Google Scholar

10. Hillis AE, Wityk RJ, Beauchamp NJ, et al: Perfusion-weighted MRI as a marker of response to treatment in acute and subacute stroke. Neuroradiology 2004; 46:31–39Google Scholar

11. Rosenblatt A, Leroi I: Neuropsychiatry of Huntington’s disease and other basal ganglia disorders. Psychosomatics 2000; 41:24–30Google Scholar

12. Marsh L: Neuropsychiatric aspects of Parkinson’s disease. Psychosomatics 2000; 41:15–23Google Scholar

13. Lyketsos CG, Sheppard JME, Steele CS, et al: Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial of sertraline in the treatment of depression complicating Alzheimer’s disease: initial results from the Depression in Alzheimer’s Disease study. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1686–1689Google Scholar

14. McKhann GM, Albert MS, Grossman M, et al: Clinical and pathological diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia and Pick’s disease. Arch Neurol 2001; 58:1803–1809Google Scholar

15. Lee HB, Hening WA, Allen RP, et al: Race and restless legs syndrome symptoms in an adult community sample in east Baltimore. Sleep Med 2006; 7:642–645Google Scholar

16. Robinson RG, Starkstein SE: Mood disorders following stroke: new findings and future directions. J Geriatr Psychiatry 1989; 22:1–15Google Scholar

17. Mace NL, Rabins PV: The 36-Hour Day: A Family Guide To Caring for Persons with Alzheimer’s Disease, Related Dementing Illnesses, and Memory Loss in Later Life. New York, Warner Books, 2001Google Scholar

18. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Google Scholar

19. Rosenberg PB, Onyike CU, Katz IR, et al: Depression of Alzheimer’s disease study: clinical application of operationalized criteria for “Depression of Alzheimer’s Disease.” Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005; 119–127Google Scholar

20. Lyketsos CG, Steinberg M, Tschantz J, et al: Mental and neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: findings from the Cache County study on memory in aging. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 708–714Google Scholar

21. Rabins PV, Arciniegas DB: Pathophysiology of involuntary emotional expression disorder. CNS Spectr 2007; 12:17–22Google Scholar

22. McHugh PR, Slavney PR: The Perspectives of Psychiatry. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998Google Scholar

23. Rao V, Handel S, Vaishnavi S, et al: Psychiatric sequelae of traumatic brain injury: a case report. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:728–735Google Scholar

24. Lyketsos CG, Rabins PV, Lipsey JR, et al (eds): Psychiatric Aspects of Neurologic Diseases: Practical Approach to Patient Care. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2008Google Scholar

25. Rao V, Spiro J, Rastogi P, et al: Prevalence and types of sleep disturbances acutely after traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 2008; 22:381–386Google Scholar