Neuropsychological Outcome of Ventral Capsular/Ventral Striatal Gamma Capsulotomy for Refractory Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Pilot Study

METHODS

A detailed description of the methodology employed in this project can be found elsewhere. 1 In brief, patients received written and oral information regarding the benefits and possible side effects/complications of the procedure, and all gave written informed consent, witnessed by a member from the Brazilian OCD Patients Foundation. The interviews and the informed consent process were videotaped and analyzed by an Independent Review Board, which verified the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committees of the University of São Paulo School of Medicine Hospital das Clínicas and the Brazilian National Commission on Research Ethics.

Sample Selection

Inclusion criteria were as follows 1 : patients between the ages of 18 and 55 years old; presenting obsessive-compulsive symptoms for at least 5 years; scoring higher than 26 (or greater than 13, for isolated obsessions or compulsions) on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) 4 ; meeting the DSM-IV criteria for a diagnosis of OCD as the principal entity 5 ; and being identified as a treatment refractory patient based on the “best estimate” method, which consists of careful examination of the patient history by two OCD specialists. Refractoriness to treatment was defined using the following criteria: having undergone empirical treatment with at least three (selective or not) serotonin reuptake inhibitors (one of which was clomipramine); having been under drug therapy for a minimum of 12 weeks at the maximum doses or the maximally tolerated doses; having participated in a cognitive behavior therapy program for a minimum of 20 hours (or participation for some time, without subsequent adherence, due to severe OCD symptoms) and acceptance by an independent review board; presenting a less than 25% reduction in Y-BOCS scores after appropriate drug therapy and psychotherapy; scoring no better than “minimal improvement” on the Clinical Global Impression Scale by the end of appropriately conducted pharmacological trials; and having been treated with at least two augmentation strategies (such as the addition of a typical or atypical neuroleptic, a benzodiazepine or another serotonin reuptake inhibitor) in appropriate doses for a sufficient period of time without a satisfactory response.

Patients with a history of head injury/posttraumatic amnesia, neurological/general medical condition or physiological effects of a substance (psychopathological symptoms) were excluded, as were pregnant or lactating patients, as well as those who refused to give written informed consent or who presented inability to understand the consent form, as determined through neuropsychological tests.

In the 2003–2004 period, five patients (two men and three women; mean age, 35±11.07 years old) met the criteria and were selected. Most were single, and all had suffered from disabling symptoms/psychosocial impairment for more than 5 years. Patients A, C, and E had been unable to complete university due to obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Only one patient (D) was employed at the time of the surgery. Although it was not possible to ensure that every patient would comply, we attempted to maintain preoperative regimens (in terms of medications and dosages) throughout the postoperative follow-up period. For the first 3 months following the procedure, all patients attended cognitive behavior therapy (CBT, 20 sessions) that was similar to that received prior to the procedure. Although we could not guarantee that every patient would be administered CBT by the same therapist, the protocol employed was the same as that used in previous psychotherapeutic trials.

Most adverse events were transient. Patient C reported migraines and patient D presented throat swelling for 2 weeks, which we attributed to the prolonged cervical posture during the surgery. In one case, the patient presented persistent headache, but MRI scans revealed no evidence of brain edema.

Instruments

The Y-BOCS, 4 Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), 5 and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) 6 were administered. The neuropsychological battery consisted of the following: tests of attention (Trail Making test A and B), 7 executive functions (Block Design subtest and Trail Making B), and memory (Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test 8 ; the Logical Memory subtests of the Wechsler Memory Scale—Revised 9 ; and the tests of intellectual functions that compose the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, 10 including the Vocabulary subtest (for expressive vocabulary), the Similarities subtest (for abstract verbal reasoning), the Matrix reasoning subtest (for nonverbal reasoning), and the Block Design subtest (for nonverbal problem solving).

Treatment Response Criteria

The response criteria were defined as a reduction of at least 35% in Y-BOCS scores and an “improved” or “much improved” score on the Clinical Global Impression Scale at 12 months after the procedure. We defined change on the neuropsychological test as equal to or greater than 1 z score.

Operative Technique

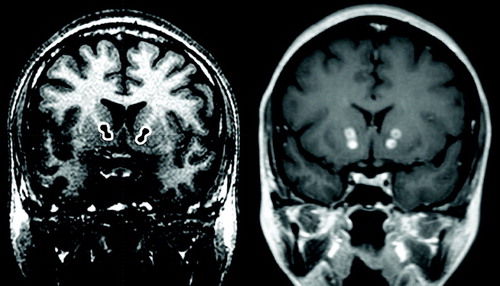

Bilateral double shots were targeted at the more ventral portions of the anterior limb of the internal capsule, immediately in front of the anterior commissure, at the anterior commissure-posterior commissure line, by converging collimated beams of gamma radiation from 201 60 Co sources using 4 mm collimators ( Figure 1 ). The target in the anterior internal capsule received 50% isodoses; the maximum dose of absorbed radiation is 180 Gray. 1

RESULTS

Individual Findings

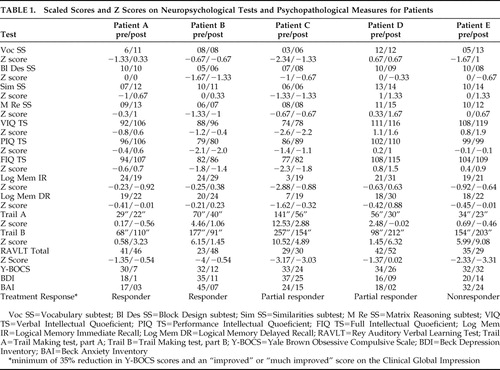

Table 1 shows the scaled scores and z scores on neuropsychological tests and psychopathological measures for the five patients submitted to ventral capsular/ventral striatal gamma capsulotomy.

|

Patient A, a 23-year-old man, met our response criteria and was still a responder 3 years after the procedure. Postoperatively, his Y-BOCS, BDI, and BAI scores decreased, suggesting improvement in obsessive-compulsive, depressive, and anxiety symptoms. He performed better on measures of full IQ, mainly due to improved performance on Vocabulary and Similarities subtests, and was slower on the Trail Making test, part B (divided attention).

Patient B, a 42-year-old woman, met our response criteria and was still a responder 3 years after the procedure. The psychopathological scale results suggested postoperative improvement in obsessive-compulsive symptoms, depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms. She scored higher for sustained and divided attention (Trail Making test, parts A and B) as well as for verbal learning (Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test).

Patient C, a 49-year-old woman, responded partially after 12 months. Clinically, the obsessive-compulsive symptoms presented a variable course, with minimal improvements in the depressive and anxious symptoms. In the third month of follow-up treatment, she was briefly hospitalized due to severe depressive symptoms. She improved in the second year and was still a responder 3 years after the procedure. At 12 months after the procedure, she performed better on attention measures, the Vocabulary subtest and memory tests (recall of contextualized information).

Patient D, a 36-year-old woman, responded partially after 12 months and was still a partial responder 3 years after the procedure. Although presenting only minimal improvements in her Y-BOCS score, her BDI and BAI scores increased 7 points after 12 months and 14 points after 9 months, respectively. She also improved on the sustained attention test, nonverbal reasoning (Matrix reasoning), memory, and learning scores. Nevertheless, her divided attention score dropped.

Patient E, a 25-year-old man, did not respond after 12 months and was still a nonresponder 3 years after the procedure. By postoperative month 6, his BDI score had dropped by 10 points, although his Y-BOCS score was unchanged, and after 3 months of treatment, his anxiety symptoms improved significantly, remaining constant for 2 years after the procedure. No obsessive-compulsive symptom improvements were observed, even when intensive inpatient CBT was administered during the second year of follow-up treatment. Although sustained attention, verbal IQ, vocabulary, similarities and recall of contextualized information improved, divided attention score and learning (total words recalled on the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test) worsened.

Group Findings

Intellectual Functioning

Although overall intellectual performance improved for the entire group, only one patient met our criteria for improvement. On the Vocabulary subtest, three patients demonstrated greater expressive vocabulary and answers that were more objective and “straight to the point,” as well as presenting fewer hesitations. Two patients (A and E) scored higher on the Similarities subtest, suggesting improved abstract verbal reasoning ability. On the Matrix Reasoning subtest, two patients (A and D) performed better, and three (patients B, C, and E) maintained the same results. There were no changes in the Block Design test results.

Attention

Postoperatively, four patients scored higher for sustained attention, completing the task faster, whereas three scored lower for divided attention.

Learning Abilities

Total words recalled on the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test increased in two patients (B and D), decreased in one (E), and remained unchanged in two (A and C).

Amnestic Functions

Recall of contextualized information (immediate and delayed recall) improved in two patients (C and D).

DISCUSSION

We found improvement in expressive vocabulary, verbal reasoning, sustained attention, verbal learning, and memory. However, decreased capacity to divide attention between stimuli was observed in three patients. Previous studies, evaluating more extensive lesions of the internal capsule (thermo and gamma knife procedures), have reported executive deficits ranging from subtle 11 , 12 to more severe. 13 The present study employed smaller, more ventrally located lesions of the internal capsule, which could have a different impact on cognitive outcomes.

We hypothesize that the postoperative improvements in verbal learning, memory, and expressive vocabulary seen in our patients were secondary to the higher postoperative sustained attention scores. This cognitive improvement could in turn be secondary to improvements in obsessive-compulsive symptoms, depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms, although the small sample size precluded formal statistical testing. These observations might also reflect functional circuitry changes arising from the surgical procedure, although these changes were also found in a nonresponder. Lesion of the internal capsule would be expected to alter information flow in the orbitothalamic and thalamocingulate circuitry. By targeting the internal capsule ventrally, our procedure could have affected orbitofrontal and medial frontal projections, 14 thereby increasing function in dorsolateral prefrontal circuits and thus improving attention. Decreases in divided attention could suggest executive deficits (lowered capacity to multitask). 11 – 13

This pilot study is the first to assess neuropsychological outcomes of ventral gamma capsulotomy. In contrast with the findings of previous studies, 13 we did not observe any frontal lobe cognitive deficits. Although formal tests of executive functions were not included in the test battery, signs of executive dysfunction, such as intrusions, contaminations and perseverations, would have been indirectly observed on the other tests of our battery. The findings of this study should be interpreted cautiously, for several reasons. For instance, the sample was small, which precluded a formal statistical analysis. However, preliminary analysis of these data using the Wilcoxon test for nonparametric data, even allowing for the small sample size, revealed significant improvement on full IQ (p=0.04), verbal IQ (p=0.04), vocabulary subtest (p=0.04), Trail Making test A (p=0.04), and logical memory delayed recall (p=0.04). There was no comparison group, and drug effects were not evaluated. In addition, this methodological design does not allow us to determine the effects of learning on neuropsychological performance. Finally, it is also possible that postoperative CBT had an impact on symptom improvement and thus on cognition. However, patient E, despite presenting no change in obsessive-compulsive symptoms, demonstrated cognitive improvements.

Our findings suggest that ventral gamma capsulotomy is not associated with profound cognitive deficits. Quite on the contrary, we observed improvements in some cognitive domains. Although this cognitive improvement might be secondary to amelioration of obsessive-compulsive symptoms, it could also reflect neurocircuitry changes associated with the surgical procedure itself.

1. Lopes AC: Ventral capsular and ventral striatal gamma capsulotomy in obsessive-compulsive disorder: initial assessment of efficacy and profile of adverse events (thesis), University of São Paulo Medical School, 2007, p 277. Available at http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/5/5142/tde-23102007-111209/Google Scholar

2. Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL: Treatment strategies for chronic and refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58(suppl 13):9–13Google Scholar

3. Noren G, Rasmussen SA, Greenberg BD, et al: Gamma capsulotomy for obsessive compulsive disorder. Rolling Meadows, Ill, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, 2002. Available at www.aans.org/library/article.aspx?ShowMenu=false;&ShowPrint;=false&ArticleId=12171Google Scholar

4. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al: The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, I: development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:1006–1011Google Scholar

5. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 41:561–571Google Scholar

6. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, et al: An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 1988; 56:893–897Google Scholar

7. Spreen O, Strauss E: Trail Making Test, in A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests, 2nd ed. New York, Oxford University Press, 1998, pp 533–547Google Scholar

8. Rey A: Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, in L’Examen Clinique en Psychologie. Paris, Press Universitaires de France, 1964Google Scholar

9. Wechsler D: Logical memory, in Wechsler Memory Scale, 3rd ed. San Antonio, Psychological Cor (Harcourt Brace & Company), 1997Google Scholar

10. Wechsler D: Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI). San Antonio, Psychological Cor, 1999Google Scholar

11. Nyman H, Mindus P: Neuropsychological correlates of intractable anxiety disorder before and after capsulotomy. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1995; 91:23–31Google Scholar

12. Nyman H, Andreewitch S, Mindus P, et al: Executive and cognitive functions in patients with extreme obsessive-compulsive disorder treated by capsulotomy. Appl Neuropsychol 2001; 8:91–98Google Scholar

13. Rück C: Capsulotomy in Anxiety Disorders. Stockholm, Karolinska University Press, 2006Google Scholar

14. Rauch SL: Neuroimaging and neurocircuitry models pertaining to the neurosurgical treatment of psychiatric disorders. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2003; 14:213–223Google Scholar