Psychiatric Comorbidities in Dandy-Walker Variant Disorder

To the Editor: The term “Dandy-Walker complex” has been used to denote Dandy-Walker malformation, the Dandy-Walker variant, and megacisterna magna 1 together. The Dandy-Walker variant is defined as cerebellar dysgenesis, without enlargement of the posterior fossa and with variable degree of hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis. 2 The commonly mentioned symptoms are developmental delay, mental retardation, cerebellar ataxia, and symptoms of hydrocephalus. 3 The psychiatric dimensions of the Dandy-Walker syndrome have not been elaborated adequately in the literature. We report a case of Dandy-Walker variant presenting with a multitude of psychiatric manifestations with a special focus on the causative role of cerebellar defect in attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Case Report

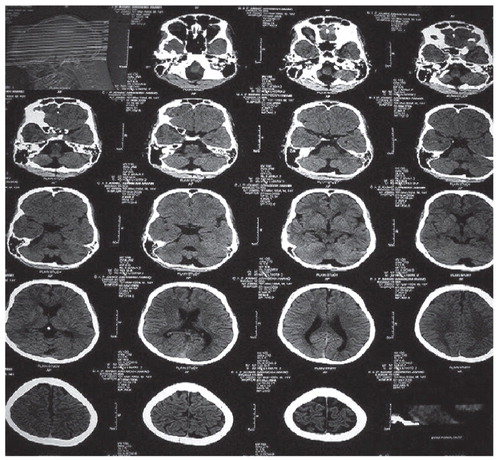

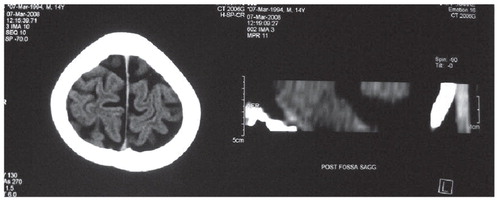

A 14-year-old-male was brought in with complaints of remaining overactive; not sitting in place; poor comprehension at school and at home since the ages of 4 and 5; throwing temper tantrums; abusive, assaultive, and destructive behavior; lying and stealing; and continuously rubbing both index fingers around the respective thumbs for the past 5 years. His birth history was normal. He didn’t have any contributory family history. He had multiple earlier psychiatric consultations, but he did not become compliant on any of them. The mental status examination revealed an overactive patient, not remaining in one place for more than a couple of minutes. His stereotypical movement of rubbing both index fingers around his thumbs would disappear when he was involved in other activities, but physical examination revealed hardening at the sites of the fingers and thumbs where he rubbed them. His IQ came to be 58. Subsequently he was diagnosed with hyperkinetic conduct disorder (Conners Rating Scale score=18) with mild mental retardation, stereotypic movements, and nocturnal enuresis. His routine investigations as well as ultrasound of abdomen and electroencephalogram were normal. His CT brain scan revealed the following abnormalities: the fourth ventricle was more prominent; the fourth ventricle was communicating with a small posterior fossa cyst; the cerebellar tonsils were separated by more than usual distance; the most inferior vermis was not clearly seen, implicating that it was hypoplastic; and the cerebral sulci, bilateral sylvian fissures, and bilateral cisterns were prominent ( Figure 1 and Figure 2 ). The posterior fossa was normal in size. The impression made by the consulting radiologist was that it was Dandy-Walker variant. The patient was given symptomatic pharmacological treatments for his nocturnal enuresis and for his hyperactivity along with behavioral therapy for his destructive behavior, hyperactive behavior, and his repetitive finger movements. After 2 weeks of treatments, his night time bedwetting stopped completely, as well as his overactive and destructive behavior after 1.5 months (a fall of 80% in Conners Rating Scale score). His repetitive finger movements reduced about 50%.

Discussion

Our case can be explained just on the basis of comorbidities in ADHD. However, the neuropathological bases of these coexistences are not clearly known.

As mentioned before, mental retardation is fairly common with the malformations of Dandy-Walker complex. Other features presented in our patient (i.e., the conduct disorder, hyperkinetic disorder, stereotypic movements, and nocturnal eneuresis) have not been reported together in association with Dandy-Walker variant in the literature to the best of our knowledge. This could have been due to the rarity of this condition. The exact role of the cerebellum in these disorders is not known. It has been suggested by various studies that the cerebellum is involved in subserving attention. However, cerebellocerebral connections are more important rather than cerebellum in this context. 4 More direct relation of a vermian defect comes from the morphometric MRI studies which have shown that the vermal volume is less in individuals with ADHD. This reduction has been found to involve mainly the posterior inferior lobe but not the posterior superior lobe, 5 consistent with the CT finding of our patient. However, such studies have been few and the vermian defect has not been severe enough so as to be called hypoplasia. Association of cerebellar abnormality with stereotypic movements is an atypical finding and any link between them is a matter of speculation.

1. Barkovich AJ, Kjos BO, Norman D, Edwards MS: Revised classification of posterior fossa cysts and cystlike malformations based on the results of multiplanar MR imaging. Am J Neuroradiol 1989; 10:977–988Google Scholar

2. Harwood-Nash DC, Fitz CR: Neuroradiology in infants and children, vol 3. St Louis, Mo, Mosby, 1976, pp 1014–1019Google Scholar

3. Notaridis K, Ebbing P, Giannakopoulos C, et al: Neuropathological analysis of an asymptomatic adult case with Dandy-Walker variant. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2006; 32:503–522Google Scholar

4. Timmann D, Daum I: Cerebellar contributions to cognitive functions: a progress report after two decades of research. Cerebellum 2007; 6:159–162Google Scholar

5. Berquin PC, Giedd JN, Jacobsen LK, et al: Cerebellum in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a morphometric MRI study. Neurology 1998; 50:1087–1093Google Scholar