Progression of Vascular Depression to Possible Vascular Dementia

To the Editor: The concept of vascular depression includes depression, vascular disease, vascular risk factors, and the association of ischemic cerebral lesions with behavioral symptoms. 1 Memory deficits are known to occur during depression: deficit in recollecting stored information in a depressed individual is known as “pseudo dementia.” Older adults with depression have an increased risk of developing mild cognitive impairment (MCI), which seems to be independent of underlying vascular disease. 2 Older adults with depression also have an increased risk of developing dementia, but whether that risk is enhanced on a background of cerebral vascular pathology is still unclear. 3 We strive to clarify this uncertainty with this report.

Case Report

Mrs. S, a 51-year-old woman, was treated with amlodipine, losartan, atorvastatin, clopidogrel, and aspirin for 8 years of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, double vessel coronary artery disease, and carotid vessel disease. She presented with a continuous illness of 2 years characterized by pervasive sad mood, decreased energy, hopelessness, early morning awakening, worsening of mood in the morning, loss of appetite, and loss of taste. Memory disturbances and significant impairment in functioning surfaced 6 months prior to consulting us. She had been treated with an adequate trial of nortriptyline and pramipexole with a partial response and an adequate trial of escitalopram and trazodone (including augmentation with quetiapine) with no response. We identified a family history of bipolar illness in her sister and hypertension and ischemic heart disease in both her parents and maternal uncle. On mental status examination with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, she was depressed (HAM-D =32) and had memory deficits. In view of the cerebral lesions, a diagnosis of organic depressive disorder was made according to ICD-10. Conceptually, vascular depression was considered with the possibility that it may be progressing to vascular dementia.

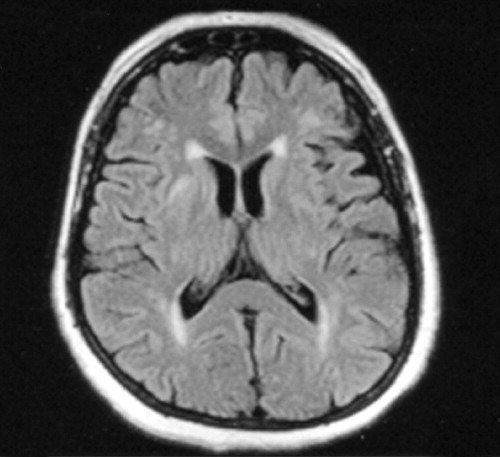

An MRI of her brain revealed multiple white matter abnormalities (hyperintensities) in bilateral frontal and parietal-occipital white matter, bilateral lentiform nuclei, and head of right caudate and right thalamus ( Figure 1 ). In view of cognitive deficits, she was subjected to a neuropsychological assessment after her depressive symptoms remitted to avoid false positive findings. She had impaired motor speed, verbal and visual working memory, and decreased speed of processing and category fluency. Immediate recall was impaired, but she benefitted from recognition testing. She was treated with gradually increasing doses of mirtazapine tablets, from 15 mg/day to 60 mg/day, which later required augmentation with a 150 mg bupropion tablet once a day. Her antihypertensive was changed from amlodipine to nimodipine capsules, 180 mg/day. She was then started on 5 mg of donepezil tablets at bedtime.

Discussion

The diagnosis of vascular depression was evident with pervasive depressed mood occurring on a background of familial vascular risk factors, cerebrovascular risk factors, and cerebral vascular pathology. To confirm the diagnosis, we used a modified Fazekas classification system, which provides an estimate of the degree of deep white matter and subcortical gray matter hyperintensities. 4 , 5 According to this scale, our patient scored more than 2 on both deep white matter and subcortical gray matter hyperintensities. It thus ruled out a differential of severe depressive disorder without psychotic symptoms. Since our patient benefitted from recognition testing, the dissociation between immediate recall and recognition suggests that the memory impairments were a result of a subcortical disease process.

Despite recovery from depressive symptoms, the cognitive deficits were irreversible at 5 months’ follow-up with persisting impairment of functioning, which convinced the treating team about progression to dementia. According to ICD-10, the diagnosis of dementia requires the presence of both cognitive and functional impairment for at least 6 months, and our patient did not have memory deficits or functional impairment during the first 1.5 years of her illness. However, one may argue that dementia could have occurred earlier, but we do not have any evidence to support it. Bupropion was chosen as augmentation to antidepressant therapy as few reports mention usefulness in vascular depression. 6 Nimodipine replaced amlodipine, as its role in augmentation with antidepressant therapy for vascular depression is known to cause a greater reduction in depressive symptoms. 7 Donepezil was added due to its growing efficacy in vascular dementia. 8

Though we know that depression in the elderly can progress to dementia, we are still in the dark as to who among these patients are prone to do so. This case underlines the fact that cerebral vascular pathology may be a common factor linking such a progress. The fact that the depression was resistant to treatment could also emphasize the organic nature of the disorder. Though our patient did not have a stroke, familial risk factors and cerebral vascular lesions were contributory to vascular depression. There is a need to understand the natural course of patients with pure vascular lesions without any history of stroke. Follow-up of those who develop dementia, factors influencing such a progress, and the rate of such a progression are also necessary. Managing depression in the elderly by treating depression alone may not suffice; physicians should also be vigilant about the various possibilities that could arise.

1. Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, et al: Vascular depression hypothesis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:915–922Google Scholar

2. Barnes DE, Alexopoulos GS, Lopez OL, et al: Depressive symptoms, vascular disease, and mild cognitive impairment findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:273–280Google Scholar

3. Jorm AF: History of depression as a risk factor for dementia: an updated review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2001; 35:776–781Google Scholar

4. Krishnan KR, Hays JC, Blazer DG: MRI-defined vascular depression. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:497–501Google Scholar

5. Sneed JR, Rindskopf D, Steffens, DC, et al: The vascular depression subtype: evidence of internal validity. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 64:491–497Google Scholar

6. Steffens DC, Taylor WD, Krishnan KRR: Progression of subcortical ischemic disease from vascular depression to vascular dementia. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1751–1756Google Scholar

7. Taragano FE, Allegri R, Vicarioet A, et al: A double blind randomized clinical trial assessing the efficacy and safety of augmenting standard antidepressant therapy with nimodipine in the treatment of vascular depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 16:254–260Google Scholar

8. Black S, Román GC, Geldmacher DS, et al: Efficacy and tolerability of donepezil in vascular dementia: positive results of a 24-week, multicenter, international, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Stroke 2003; 34:2323–2332Google Scholar