Multiple Embolic Phenomenon in the Brain Associated With Parenteral Buprenorphine Abuse

To the Editor: Buprenorphine in sublingual form is a partial opiate agonist which has been approved in various countries for the treatment of opioid dependence. Illicit diversion of buprenorphine, whereby it is injected parenterally, and the medical sequalae have been reported by various authors. 1 , 2

We have seen several cases of patients who have abused intravenous and intra-arterial buprenorphine, and we present one such case. This is a woman in her mid-forties who presented for admission complaining of blurred vision after a session of buprenorphine abuse by injection into the neck vessels. She had a history of opioid abuse and dependence since age 17 using primarily intravenous heroin. Periods of abstinence occurred only when she was in resident drug treatment programs. In 2003, she was started on a regimen of sublingual buprenorphine (Subutex®) by a family physician. However she quickly started using Subutex® intravenously to achieve a high. She described grinding 1–3 prescription Subutex® tablets into a powder form, mixing it with hot water, and then injecting it intravenously. She denied adding other substances into the mixture. When she encountered difficulty with venous access, she started using her left radial artery. Two months prior to admission, she started having a friend inject into her neck vessels, both into the jugular vein and carotid artery. This occurred over 10 occasions, the most recent being a few days prior to this admission. Then she reported an onset of blurred vision that waxed and waned.

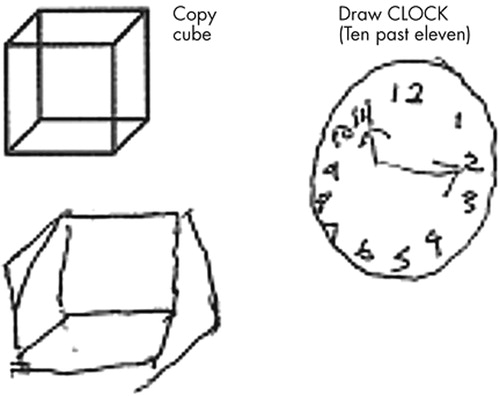

Her other medical problems included a history of subacute bacterial endocarditis. She did not have a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or previous strokes. Neurological exam on admission was within normal limits. She was assessed by an ophthalmologist who detected no abnormality. Psychiatric interview revealed a history consistent with opioid dependence but no other overt psychiatric disorder. However, she was experiencing symptoms of opioid withdrawal and craving and was relatively less concerned about her problems. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was 25/30. Montreal Cognitive Assessment, 3 which has been shown to be sensitive in screening for mild cognitive impairment, was performed. The result of 24/30 is consistent with mild cognitive impairment. In particular, she had difficulty with copying a cube and clock drawing ( Figure 1 ), suggesting an involvement of the visuospatial system. Other areas of cognitive functioning including memory were largely intact.

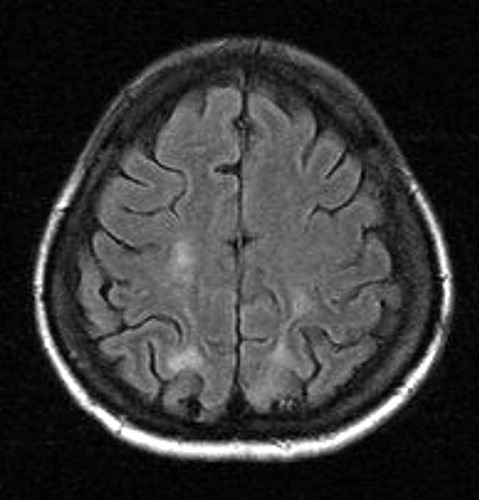

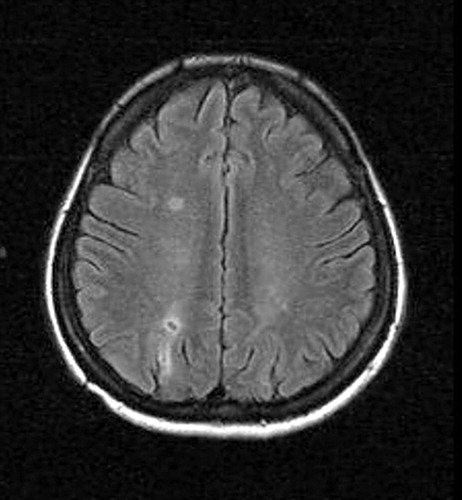

MRI showed several foci of T 2 and FLAIR hyperintensity in the temporal and parietal lobes bilaterally and also in the right frontal lobe. There was corresponding hyperintensity of these foci on diffusion weighted imaging that were consistent with multiple embolic infarcts ( Figure 2 and Figure 3 ).

Her visual disturbance, described as vague and fluctuating visual difficulties, resolved during the hospital admission. She was discharged on follow up with substance abuse and neuropsychiatry services.

Comment

Intravenous drug abuse has been associated with multiple medical problems; parenteral (both intravenous and intra-arterial) injections into the carotid artery could directly and indirectly lead to damage of the brain vasculature and parenchyma. To the best of our literature search we have not found published information pertaining to embolic phenomenon associated with parenteral burprenorphine. Of great interest also is the observation that such gross radioimaging findings did not correlate commensurately with significant, overt neuropsychiatric impairment. Instead the clinical symptoms appeared to abate with time.

Multiple embolic infarcts in the brain have been associated with aortic arch atheroma, atrial fibrillation, atrial myxoma and aneurysm, cardiomyopathy, infective endocarditis, carotid artery, and cardiac procedures. 4 The pattern of infarction has been reported to depend on embolic load, type, composition, and size of particles. Such particles include air bubbles, calcified particles, fibroelastomic tissue, and platelet fibrin particles. 5 Hence it can be inferred that the particulate size and constituents of ground buprenorphine and the water used may have a bearing on the embolic infarct. It is conceivable that a large injection of powdered drug could cause a shower of particulate emboli in the brain.

It would not always be possible to distinguish whether the embolic phenomenon is caused by or associated with this patient’s subacute endocarditis or the parenteral buprenorphine or both, which, in our view, is most likely the case. Moreover, temporally it is likely that the multiple episodes occurred over several months and the neuropsychiatric and radiologic sequalae were due to a cumulation of multiple successive insults. More investigation is merited to understand the etiology, pathophysiology and treatment of multiple particulate embolism due to intravascular injection of substances. We also recommend that patients who abuse substances parenterally and present with neuropsychiatric symptoms undergo detailed neuropsychiatric assessment, including appropriate imaging.

1 . Chua SM, Lee TS: Abuse of prescription buprenorphine, regulatory controls and the role of the primary physician. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2006; 35:492–495Google Scholar

2 . Yeo AK, Chan CY, Chia KH: Complications relating to intravenous buprenorphine abuse: a single institution case series. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2006; 35:487–491Google Scholar

3 . Nasreddine ZS, Chertkow H, Phillips N, et al: The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): a brief cognitive screening tool for detection of mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 2004; 62:A132Google Scholar

4 . Wein TH, Bornstein NM: Stroke prevention: cardiac and carotid-related stroke. Neurol Clin 2000; 18:321–341Google Scholar

5 . Babikian VL, Caplan LR: Brain embolism is a dynamic process with variable characteristics. Neurology 2000; 54:797–801Google Scholar