Paroxysmal Kinesigenic Dyskinesia and Cervical Disc Prolapse With Cord Compression: More Than a Coincidence?

To the Editor: Paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia (PKD) is a relatively rare neurological condition which is characterized by sudden, brief (seconds to 5 minute) attacks of involuntary movements which are precipitated by sudden voluntary movement. 1 Although often inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, the pathophysiology of the disease remains largely unknown. 2 Besides evidence supporting the paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia as a form of epilepsy or basal ganglia disorder, many patients with symptomatic movement disorders have also been associated with a focal lesion. 1 These reported lesions are distributed widely from the cerebral cortex to the spinal cord and make the pathophysiological correlation difficult.

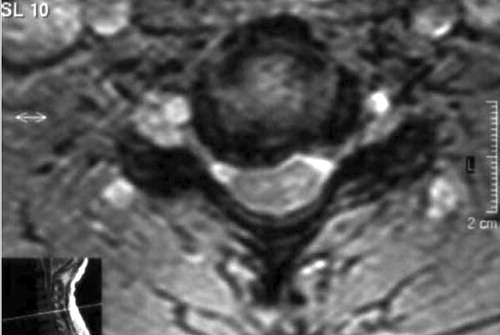

A 43-year-old male was admitted because of paroxysmal abnormal movements. There was no family history of paroxysmal movement disorders, seizures, or epilepsy. Ictal electroencephalograms of his attacks without loss of consciousness or a seizure were normal. The neurologic examination demonstrated choreiform movements of proximal and distal parts of the right arm and fingers, especially when he moved his right arm suddenly. But interestingly, the same dyskinetic movements did not appear when the patient was asked to get up from the sitting position and walk or when the patient was resting quietly or moved his other limbs. These movements appeared suddenly and lasted for 15–30 seconds. His face and the other upper limbs were not affected. Motor examination showed mild right monoparesis (grade 4/5) and minimally increased tone and hyperreflexia with no clonus on the right upper extremity. Systemic and blood examination was otherwise unremarkable. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of cervical spine revealed multiple prolapsed discs at the C3-4, C4-5, C5-6 and C6-7 levels; severe cord compression was more prominent at the C5-6 level ( Figure 1 and Figure 2 ). Brain MRI scan did not show any abnormalities. Interictal electroencephalograms were normal. Electroneuromyography suggested mild C7-8 radix involvement but the electrophysiologic evidence of posterior column abnormality on somatosensory evoked potential examination was not shown. The patient was treated with carbamazepine, 100 mg twice daily, which was remarkably effective in stopping the attacks.

Note the significant cord compression at the C5-6 level.

Discussion

The modulation of movement at spinal level is thought to be in a computerized manner whereas the supraspinal and the peripheral afferent inputs are well integrated into the evolution of the movement. 3 Altered sensory input (in particular proprioceptive pathways), abnormal processing of both input and output signals in the spinal interneurons, and increased excitability of the spinal motor neurons have been hypothesized to play an important role in the development of movement disorders in cervical cord lesions. Although we have excluded possible epileptic phenomena, it seemed very interesting that a small dosage of carbamazepine was remarkably effective in stopping the attacks. This may be explained on the basis of altered sodium channels due to the extrinsic cord compression as suggested by previous experimental studies. 4 , 5 However, the anticonvulsant agents that are preferable by spinal dysesthesias with their potential effect on ion channels could also suggest the role of spinal channel blockage in controlling these dyskinesias. This case emphasizes that spinal cord compression may also be considered in every patient with the clinical symptoms of cervical disk prolapse and movement disorders.

1 . Demirkiran M, Jankovic J: Paroxysmal dyskinesia: clinical features and classification. Ann Neurol 1995; 38:571–579Google Scholar

2 . Bennett LB, Roach ES, Bowcock AM: A locus for paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia maps to human chromosome 16. Neurology 2000; 54:125–130Google Scholar

3 . Prochazka A, Mushahwar VK: Spinal cord function and rehabilitation: an overview. J Physiol 2001; 533:3–4Google Scholar

4 . Fehlings MG, Agrawal S: Role of sodium in the pathophysiology of secondary spinal cord injury. Spine 1995; 20:2187–2191Google Scholar

5 . Schwartz G, Fehlings MG: Evaluation of the neuroprotective effects of sodium channel blockers after spinal cord injury: improved behavioral and neuroanatomical recovery with riluzole. J Neurosurg 2001; 94:245–256Google Scholar