Clinical and Neuropsychological Profiles of Obsessive-Compulsive Schizophrenia

Abstract

This pilot study compared characteristics of obsessive-compulsive (OC) schizophrenic patients and a matched non-OC schizophrenic control group. The OC-schizophrenic group required more intensive clinical interventions and had a poorer clinical course, lower levels of functioning, and longer periods of hospitalization. They showed greater negative symptoms and more impaired executive functioning. These findings suggest OC-schizophrenic patients may have an atypical set of clinical and neuropsychiatric characteristics, perhaps constituting a subgroup within the schizophrenia spectrum. Pathophysiology and possible treatment implications require further study.

The clinical phenomenon of obsessive-compulsive (OC) symptoms coexistent with schizophrenia has intrigued clinicians for over a century. In the 19th century, Westphal1 considered OC symptoms to be either a prodrome or an integral part of schizophrenia, as did Bleuler2 earlier in this century. Others reported that such comorbidity was rare and suggested that schizophrenic patients with OC symptoms had a comparatively benign clinical course.3 More recent evidence, however, suggests a higher rate of coexisting OC and schizophrenia than was previously thought, a finding supported by various clinical observations.4–7 Furthermore, in a recent review, Hollander8 found that OC symptoms coexist with a diverse range of neuropsychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety, phobic and panic disorders, autism, and Tourette's syndrome. Conversely, these investigators have also noted the presence of psychotic-like overvalued ideas and delusional beliefs in several OC-spectrum disorders.

Recent clinical evidence suggests that treatment with anti-OCD medications (clomipramine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]) may result in significant symptom relief and functional improvements in some OC-schizophrenic patients. For instance, we have previously published a case in which significant improvement of OC symptoms, accompanied by selective improvement of perseverative errors on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, was accomplished with adjunctive clomipramine treatment. The patient showed a selective OC-symptom treatment response, while the positive and negative schizophrenic symptoms remained relatively unchanged.9 Other investigators have likewise reported that recognition and treatment of OC-schizophrenia as a distinct schizophrenic subgroup may lead to improved clinical outcome.10–13 We note also, however, a report of a potentially significant pharmacokinetic interaction between antipsychotics and SSRIs due to their shared hepatic metabolic pathway.14

In the present study, we investigated the clinical and neuropsychiatric features of schizophrenic subjects with severe and persistent OC features in an effort to better identify and elucidate this syndrome.

METHODS

Ten study subjects who met the DSM-III-R criteria for schizophrenia and who had operationally defined OC features were selected consecutively by screening inpatients in a large urban state hospital. They were matched for age (±5 years) and gender with schizophrenic patients without OC features (n=10). OC symptom criteria were defined as persistent and severe thoughts and/or purposeless repetitive activities meeting at least three of the operationalized symptom criteria for at least 6 months.5 The OC symptom criteria included obsessions having sexual, religious, aggressive, contamination, and/or somatic themes, with or without accompanying compulsions such as cleaning, checking, hoarding, repeating, or arranging. Patients who showed transient or variable OC symptoms were excluded from the study. Subjects were between the ages of 20 and 50 and carried a well-established DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia.15 Patients were excluded if they had other concurrent DSM-III-R diagnoses (e.g., major depression, panic disorder, substance abuse, organic brain syndrome). Subjects were 18 males and 2 females. Patients meeting study inclusionary criteria gave signed informed consent after the procedure had been fully explained.

All assessments were completed after at least 4 weeks of symptom stabilization on optimal individualized neuroleptic medication treatment. Evaluations were completed over two to three sessions in order to avoid a fatigue effect, but were completed within 10 days. To maintain the blind status, the assessments were performed by a trained research assistant who was not involved in the screening process. Screening was done by the research clinician. Demographic information was obtained from the patient's chart and via interviews with patients, clinical staff, and family members when available. Clinicians completed the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI), the Nurses' Observation Scale for Inpatient Evaluation (NOSIE),16 and the Strauss-Carpenter Scale for functional assessment.17 Trained technicians who were blind to the patients' OC status completed the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS),18 Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS),19 neurological soft signs assessment (NSS),20 and Abnormal Involuntary Movements Scale (AIMS).21 The neuropsychological battery included the automated Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST)22 and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).23

All statistical analyses were accomplished with Student's t-tests.

RESULTS

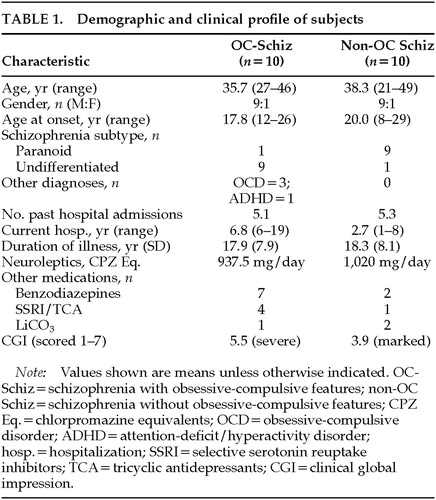

No significant differences were noted between the OC and non-OC group in terms of age, baseline IQ, age at onset, or duration of psychiatric illness. The clinical profiles of the groups, however, did reveal some important differences (Table 1). Significantly more of the OC group were diagnosed with undifferentiated schizophrenia, in contrast to the more prevalent paranoid subtype in the study setting. OC patients were also more likely to carry secondary or coexisting diagnoses such as OCD and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. The two groups had an equivalent number of past hospitalizations, but the OC group had a significantly longer current hospitalization. The OC and non-OC groups were on similar neuroleptic dosages, but the OC group took more adjunctive medications such as benzodiazepines and antidepressants (Table 1). On the CGI, OC patients had a poorer clinical course with lower levels of functioning, especially in terms of “self-care” and “social competency.”

Psychopathological assessments with the PANSS revealed significantly higher ratings in terms of the presence of negative symptoms (P<0.05) and general psychopathology (P<0.01) in the OC group. No differences were noted in positive symptom ratings (Table 2). Analysis of PANSS-derived factors revealed higher scores among OC patients on the “activation” factor, which includes impulsivity and anxiety. Groups did not differ on anergia, depression, or thought disturbance factors. On the Y-BOCS, severe OC symptomatology was noted in our OC patients (P<0.001), despite a lack of subjective distress. A trend toward greater neurological soft signs was also noted in the OC group (P<0.1), but there were no intergroup differences on the AIMS for extrapyramidal symptoms.

Results of the WCST revealed that OC patients completed significantly fewer categories (P<0.05) and made significantly more perseverative errors (P<0.01) than non-OC patients, whereas no difference was found in nonperseverative errors between the groups (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Despite interest in the OC-schizophrenia phenomenon over the years, the present investigation, to the best of our knowledge, is the first controlled study that examines specific clinical and neuropsychiatric profiles of patients with OC-schizophrenia. Notwithstanding limitations of the present study (small n, limited assessments), our findings suggest that OC-schizophrenia patients possess a distinct clinical and neuropsychological profile that differs from that of their non-OC schizophrenic counterparts. This profile includes a worse clinical course with poor treatment response, lower functioning levels, and greater impairment of functions primarily subserved by the frontal lobes. In addition, the OC-schizophrenia patients showed a higher level of negative symptoms, worse overall psychopathology, and significantly more impaired performance on WCST (a test of executive functioning), raising the possibility of greater prefrontal pathology.

The present findings support earlier reports of a relationship between prefrontal dysfunction and higher negative symptom ratings, a poorer clinical course, and lower levels of overall functioning.24–26 Our data also concur with the findings by Butler et al.,26 who observed that poorer WCST performance was associated with a greater number of negative symptoms and more hospitalizations among a group of paranoid schizophrenic patients. However, our findings differ in some interesting and potentially important ways. Whereas Butler et al. found worse WCST results among patients with paranoid schizophrenia, the present study found worse WCST performance in OC schizophrenic patients, who were predominantly of the undifferentiated subtype, compared with the predominantly paranoid, non-OC schizophrenic comparison group.

Recent functional neuroimaging study in OCD has demonstrated increased metabolic activity in the lateral prefrontal cortex,27 whereas patients with schizophrenia generally evidence prefrontal hypoactivity.28 It is also of interest that the recently introduced novel antipsychotics such as clozapine and risperidone have been associated with increased incidence of new onset or exacerbation of previous OC symptoms in schizophrenia,29 presumably because of alterations in central serotonergic activities. On the other hand, use of adjunctive anti-OCD medications has been shown to improve OCD and/or psychotic symptoms in some OC-schizophrenic patients.12,13 Although none of our study subjects were on atypical antipsychotic medication treatment, the effect of serotonergic medication on prefrontal functioning in OC-schizophrenia is intriguing and needs further exploration.

In summary, our findings indicate that OC-schizophrenic patients may possess a unique clinical and neuropsychological profile within the schizophrenic spectrum. Further, emerging evidence suggests that these patients require specific symptom-based clinical evaluations and treatment strategies for optimal outcome. At present, it is not clear whether this subgroup is best conceptualized as a distinct schizophrenic syndromal subtype with prominent OC symptom dimensions, or as a subset of schizophrenics suffering from coexisting OCD and schizophrenic process. A broadening of the accepted schizophrenic spectrum disorder may enhance understanding of the illness as well as improve care, which will positively affect the quality of the patient's life.30

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a National Research Service Award of the National Institute of Mental Health (MH19126) to the senior author.

|

|

1 Westphal K: Über Zwangsvorstellungen. Archiv für Psychiatr und Nervenkr 1878; 8:734–750Google Scholar

2 Bleuler E: Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia. Edinburg, Livingstone, 1919Google Scholar

3 Rosen I: The clinical significance of obsessions in schizophrenia. J Ment Sci 1957; 103:778–785Google Scholar

4 Karno M, Golding JM, Sorenson SB, et al: The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 45:1094–1099Google Scholar

5 Fenton WS, McGlashan TH: The prognostic significance of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:437–441Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Eisen JL, Beer DA, Pato MT, et al: Obsessive-compulsive disorder in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:271–273Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Hwang MY, Bermanzohn PC, Opler LA: Schizophrenia with obsessive-compulsive symptoms, in Management of Comorbid Conditions in Schizophrenia, edited by Hwang MY, Bermanzohn PC. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press (in press)Google Scholar

8 Hollander E: Obsessive-Compulsive Related Disorders. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

9 Hwang MY, Rho J, Opler LA, et al: Treatment of an obsessive-compulsive schizophrenic patient with clomipramine: clinical and neuropsychological findings (letter). Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1995; 8:3:231–233Google Scholar

10 Stroebel CF, Szarek BL: Use of clomipramine in treatment of obsessive compulsive symptomatology. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1984; 4:98–100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Hwang MY, Opler LA: Schizophrenia with obsessive-compulsive features: assessment and treatment. Psychiatric Annals 1994; 24:468–472Crossref, Google Scholar

12 Zohar J, Kaplan Z, Benjamin J: Clomipramine treatment of obsessive compulsive symptomatology in schizophrenic patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1993; 54:385–388Medline, Google Scholar

13 Berman I, Sapers BL, Chang HHJ, et al: Treatment of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in schizophrenic patients with clomipramine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1995; 15:206–210Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Nemeroff CB, DeVane L, Pollock BG: Newer antidepressants and the cytochrome P450 system. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:311–320Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R–Patient Version (SCID-P). New York, Biometric Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1988Google Scholar

16 Honigfeld G, Gillis R, Klett CJ: NOSIE-30: A treatment sensitive ward behavior scale. Psychol Rep 1966; 19:180–182Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Strauss JS, Carpenter WT: The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia, II: relationships between predictors and outcome variables. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974; 31:37–42Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987; 13:261–276Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al: The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS), I: development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:1006–1011Google Scholar

20 Quitkin F, Rifkin A, Klein DF: Neurologic soft signs in schizophrenia and character disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:845–853Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 National Institute of Mental Health Abnormal Involuntary Movements Scale (AIMS). Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1974Google Scholar

22 Heaton RK: A Manual for the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. Odessa, FL, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1981Google Scholar

23 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Merriam A, Kay SR, Opler LA, et al: Neurological signs and positive-negative dimensions in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1990; 28:181–192Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Opler LA, Ramirez PM, Rosenkilde CE, et al: Neurocognitive features of chronic schizophrenic patients. J Nerv Ment Dis 1991; 179:638–640Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Butler RW, Jenkins MA, Sprock J, et al: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test deficits in chronic paranoid schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1992; 7:169–176Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Baxter LR: PET studies of cerebral function in major depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder: the emerging prefrontal cortex consensus. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1991; 3:103–109Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Weinberger DR, Berman KF, Zec RF: Physiological dysfunction of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia, I: regional cerebral blood flow evidence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:114–124Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Baker RW, Bermanzohn PC, Wirshing DA, et al: Obsessions, compulsions, clozapine, and risperidone. CNS Spectrum 1997; 2:26–31Google Scholar

30 Hwang MY, Bermanzohn PC: Management of Comorbid Conditions in Schizophrenia. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press (in press)Google Scholar