Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration With Balint's Syndrome

Abstract

Corticobasal ganglionic degeneration (CBGD) is a neurodegenerative dementia characterized by asymmetric parkinsonism, ideomotor apraxia, myoclonus, dystonia, and the alien hand syndrome. This report describes a patient with CBGD who developed Balint's syndrome with simultanagnosia, oculomotor apraxia, and optic ataxia.

Corticobasal ganglionic degeneration (CBGD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder involving both cortical and basal ganglionic dysfunction. The main features of CBGD are movement disorders and dementia.1,2 It is not widely appreciated that CBGD can also produce prominent visuospatial difficulties.

Balint's syndrome is a complex visuospatial disorder. It includes the inability to integrate complex visual scenes (simultanagnosia); the inability to accurately direct hand or other movements by visual guidance (optic ataxia); and reduced or inaccurate voluntary eye movements to visual stimuli (oculomotor apraxia).3,4 This triad results in a dramatic impairment in the ability to explore visual space. This case report expands the clinical spectrum of CBGD to include Balint's syndrome.

CASE REPORT

A 65 year-old right-handed man developed “inability to see.” He had difficulty in performing visual tasks such as locating items or orienting himself in familiar surroundings. The patient behaved as if blind, unable to either look at or reach for objects in his environment.

The patient had an insidiously progressive disease of 8 years' duration. His illness began with a slow, rigid gait, abnormal posturing of his right hand, and retrocollis. As his disease progressed, he developed difficulty performing manual tasks, particularly with his left hand, such as manipulating his carpenter tools. For a period of time his left arm felt foreign, as if it “did not belong” to him, and it would sometimes elevate on its own (the “alien hand phenomenon”).5 Subsequently, the patient progressed to memory and word-finding difficulty. His past medical and family histories were otherwise unremarkable, and he was on no medications.

The patient had prominent visuospatial deficits. He was tested at his best refraction (20/70 OU), and visuospatial tasks were administered untimed. He had difficulty copying drawings such as intersecting pentagons or a cube. When presented with complex scenes such as the Cookie Theft Picture,6 he could not recognize more than one item at a time. He could not identify two adjacent but unlinked drawings (pairs of circles) or large letters made up of smaller ones.4,6 Visuospatial organization was tested with the Hooper Visual Organization Test (30 visual fragments requiring mental reconstruction for identification).6 His responses were based on a single visual fragment, and his scores did not improve even when all of the individual fragments were viewed.

The patient could not locate items in his visual field, such as the buttons on his clothes or utensils for eating. He had full extraocular movements on directional command (voluntary saccades), on pursuit, and on oculocephalic reflex stimulation; however, when commanded to move his eyes to specific visual objects in his peripheral fields, he could not do so (“oculomotor apraxia”). When attempting to reach out and touch objects in his peripheral fields with either arm, he would entirely miss them (“optic ataxia”). Infrequently, the patient experienced oculogyric crisis with a locking of his eyes in the upward direction.

On further testing, he was alert and attentive but disoriented as to place and date. His language was fluent, and he had intact auditory comprehension for simple pointing and yes-no tasks. Confrontational naming was impaired for common objects, and recent memory was 0 for 4 words at 5 minutes. Despite the absence of motor weakness, he had difficulty performing learned movements with his left arm. He was unable to brush his teeth or wave goodbye with his left upper extremity on verbal command. His attempts at performing these praxis tasks resulted in grotesque motor movements of his left upper extremity. Despite dystonic posturing of his right hand, the patient was able to perform these movements with his right arm. He did not manifest an alien hand phenomenon at the time of examination.

The rest of his neurological examination disclosed movement disturbances. He had dystonic posturing of his right hand with spread of his fingers in an athetotic fashion and retrocollic deviation of his head with elevation of his right shoulder. Spontaneous myoclonic jerks occurred in his extremities. The gait was stiff and broad-based, and tone was increased in a leadpipe rigidity. His reflexes were symmetrically brisk, and his toes were upgoing bilaterally.

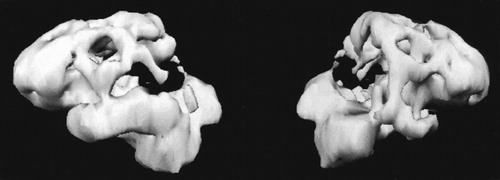

The patient underwent an extensive series of investigations. Magnetic resonance imaging showed cerebral atrophy, and SPECT imaging showed prominent decreased perfusion in posterior parietal regions and, to a lesser degree, in the dorsal frontal regions (Figure 1). After the patient was started on trihexyphenidyl 1 mg bid, the oculogyric crisis resolved and the dystonia and retrocollis decreased, but he continued to show signs of Balint's syndrome.

DISCUSSION

This patient who had symptoms consistent with CBGD developed visuospatial symptoms consistent with Balint's syndrome. Manifestations of CBGD included parkinsonism, dystonia, myoclonus, ideomotor apraxia, and a history of the alien hand phenomenon.1 Manifestations of Balint's syndrome included simultanagnosia and deficits in visually guided hand and eye movements (optic ataxia and oculomotor apraxia, respectively).

CBGD is a progressive disease characterized by movement disorders and dementia. The most common motor findings are asymmetric parkinsonism with rigidity, bradykinesia, gait disorder, and tremor.1 Most CBGD patients also have dystonia and myoclonus, and about 40 percent develop the alien hand syndrome during their course.1 The alien hand phenomenon is the sensation that an extremity is “foreign” and that it manifests spontaneous movements not under the patient's control.5 As the disease progresses, the motor signs become bilateral and dementia develops. Asymmetric astereognosia, sensory extinction, and left visual attentional difficulty may also result from CBGD;7,8 however, other sensory or visuospatial disturbances are reported infrequently. Pathology includes neuronal loss, gliosis, ballooned neurons, tau-positive achromatic inclusions, and reduced dopamine concentrations affecting the frontal and parietal cortex, basal ganglia, and substantia nigra.9 Similar to Balint's syndrome, CBGD eventually results in injury to both parietal cortices,1,2 as evidenced by parietal hypoperfusion or hypometabolism on functional neuroimaging.10

Prior investigators have reported Balint's syndrome from Alzheimer's disease, strokes, multifocal leukoencephalopathy, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.1–4 These diseases all produce bilateral neuropathology in the inferior parietal and adjacent superior occipital cortex, the lesions responsible for Balint's syndrome.1–4 There are two multisynaptic visual pathways emanating from the primary visual cortex: an inferior temporal “what” system dealing with form and color and a parietal “where” system dealing with spatial concepts.11 The occurrence of Balint's syndrome in this patient is consistent with disruption of the visual “where” system from parietal disease due to CBGD.

Two further issues must be considered in this case. First, the diagnosis of CBGD cannot be definitely established in the absence of pathology. This patient, however, had characteristic motor symptoms, including ideomotor apraxia and a history of an alien hand, as well as dementia. A second consideration is that memory and other cognitive deficits, apraxia, dystonia, and limited head movements confounded or obscured the assessment of simultanagnosia, oculomotor apraxia, and optic ataxia. In this patient, however, Balint's syndrome persisted despite compensation or improvement in the other cognitive or motor deficits on examination.

This patient illustrates Balint's syndrome as a consequence of visuospatial dysfunction in CBGD. Because of the complicating movement abnormalities and cognitive deficits of CBGD, clinicians may miss Balint's syndrome unless they test for this visuospatial syndrome.

FIGURE 1. Three-dimensional computerized reconstruction of [99mTc]HMPAO single-photon emission computed tomography scanThe left hemisphere is on the left side. There are prominent areas of decreased perfusion in the parietal lobes, bilaterally.

1 Kompoliti K, Goetz CG, Boeve BF, et al: Clinical presentation and pharmacological therapy in corticobasal degeneration. Arch Neurol 1998; 55:957–961Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Riley DE, Lang AE, Lewis A, et al: Cortical-basal ganglionic degeneration. Neurology 1990; 40:1203–1212Google Scholar

3 De Renzi E: Disorders of spatial orientation, in Handbook of Clinical Neurology, edited by Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW. Amsterdam, Elsevier Science, 1985, pp 405–422Google Scholar

4 Mendez MF, Turner J, Gilmore GC, et al: Balint's syndrome in Alzheimer's disease: visuospatial characteristics. Int J Neurosci 1990; 54:339–346Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Doody RS, Jankovic J: The alien hand and related signs. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992; 55:806–810Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Lezak MD: Neuropsychological Assessment, 3rd edition. New York, Oxford University Press, 1993Google Scholar

7 Marti Masso JF, Lopez de Munain A, Poza JJ, et al: Degeneración corticobasal: un reporte de 7 casos diagnosticados clinicamente [Corticobasal degeneration: a report of 7 clinically diagnosed cases]. Neurologia 1994; 9:115–120Medline, Google Scholar

8 Schneider JA, Watts RL, Gearing M, et al: Corticobasal degeneration: neuropathologic and clinical heterogeneity. Neurology 1997; 48:959–969Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Rey GJ, Tomer R, Levin BE, et al: Psychiatric symptoms, atypical dementia, and left visual field inattention in corticobasal ganglionic degeneration. Mov Disord 1995; 10:106–110Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Nagasawa H, Tanji H, Nomura H, et al: PET study of cerebral glucose metabolism and fluorodopa uptake in patients with corticobasal degeneration. J Neurol Sci 1996;139:210–217Google Scholar

11 Van Essen D, Maunsell J: Hierarchical organization and functional streams in the visual cortex. Trends Neurosci 1983; 6:370–375Crossref, Google Scholar