The Role of Pre-injury IQ in the Determination of Intellectual Impairment From Traumatic Head Injury

Abstract

The subjects were 17 head trauma patients whose pre-injury IQ and post-injury IQ scores on the Chinese Revised Version of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-RC) were collected and analyzed. All patients had a neuroradiological imaging study. Changes in IQ scores were compared with neuroradiological findings and clinical determinations on the presence or absence of intellectual impairment from head trauma that were made by neuropsychiatrists without knowledge of pre-injury IQ scores. Thirteen patients were clinically determined not to have suffered intellectual impairment, primarily because their post-injury IQs on the WAIS-RC were higher than 70. However, 3 of the 13 had significantly higher pre-injury IQ scores, and they also showed brain damage on CT or MRI. Consideration of pre-injury IQ can improve the determination of intellectual impairment from head injury.

Neuropsychiatrists are often called upon to assess and render expert opinions on intellectual impairment after traumatic head injury. At the Hunan Provincial Center of Expert Testimony in Forensic Psychiatry, in China, these evaluations account for about one-fifth of all cases. In the past decade, China has seen an increase in litigation involving traumatic head injury. In response to this trend, the Forensic Psychiatry Section of the Chinese Psychiatric Association proposed guidelines in 1997 on the assessment of psychological damage after head injuries. However, in practice, it is often difficult to make a confident determination of intellectual impairment after traumatic head injury.

In the clinical practice of neuropsychiatry, The conventional determination of intellectual impairment from head trauma is based mainly on a post-injury intelligence level that is usually assessed at the time of expert testimony. A determination of intellectual impairment is considered if post-injury IQ scores are less than 70 and there is no malingering and no preexisting mental retardation. This approach does not take into consideration individual differences in pre-injury IQ levels. For example, if a college professor and a manual laborer both have the same post-injury IQ of 75, both will be considered “borderline impaired” because the label “intellectually impaired” is reserved for individuals with IQs of less than 70. However, most likely the college professor has suffered a more significant intellectual deterioration than the manual laborer and will no longer be competent in his or her profession. Therefore, the determination of “borderline impairment” is clearly inappropriate for the college professor.

In the United States, several research teams have presented regression equations for the estimation of premorbid IQ scores from demographic variables.1–3 In China, Dai and Gong of the Medical Psychology Center at Hunan Medical University have also worked out the equations for estimating premorbid IQ scores on the Chinese Revised Version of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-RC) by using the demographic variables of age, sex, education, and occupation.4,5 Clinical approaches to estimation of preinjury IQ are and will continue to be important to neuropsychologists, especially those involved in the forensic arena.6 Although the methods of estimating premorbid IQ have been developed by psychologists over the past decade, there is relatively little use of these strategies, which are specifically designed to assess premorbid ability.7 This study was undertaken to examine the contribution of considering pre-injury IQ scores in the neuropsychiatric determination of intellectual impairment from traumatic head injury.

METHODS

All subjects were from the Hunan Provincial Center of Expert Testimony in Forensic Psychiatry. From October 1993 to October 1996, there were 66 cases of patients with head trauma, including 42 from assaults and 24 from motor vehicle accidents. Informed consent was obtained from every patient prior to enrollment in the study. All patients received a CT or MRI scan within 3 weeks after their injury. The WAIS-RC was administered from 6 to 18 months post-injury, at the time of clinical evaluation by forensic psychiatrists. Among the 66 patients, 27 did not finish the WAIS-RC: 4 because of physical dysfunction, 7 because of psychiatric symptoms secondary to head trauma, and 16 because of physical and emotional uncooperativeness. Among the 39 who did finish the WAIS-RC testing, the results for 22 of them (56%) were judged to be invalid because of poor effort or malingering. Therefore, only the data from the remaining 17 patients with valid post-injury IQ scores were used for analysis. The diagnosis of malingering was based on code V65.2 of DSM-IV. Additionally, the following features, if present, were taken into consideration in determining this diagnosis: 1) the physical or psychological symptoms were not in accordance with the natural features of any diseases, and/or the subjects' complaints were more severe than the findings of the laboratory or physical examinations; 2) the subjects were not cooperative with physicians, were hostile toward experts, or evaded the crucial issues; and 3) the physical or psychological symptoms disappeared when the subjects were left alone.

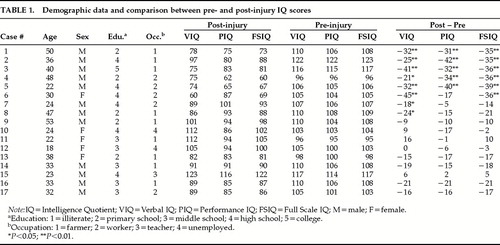

The 17 cases included 12 males and 5 females. Their age ranged from 18 to 53 years and averaged 33.7 years. All of them were right-handed and had no prior neurological illnesses or injuries. Their post-injury scores on the WAIS-RC included Verbal IQ (VIQ), Performance IQ (PIQ), and Full Scale IQ (FSIQ). Their estimated pre-injury IQ scores on the WAIS-RC were obtained with published regression equations according to their age, sex, education, and occupation.4 These IQ scores, plus the differences between the pre- and post-injury scores and the difference between the post-injury scores of VIQ and PIQ, were analyzed in relation to neuroradiological findings and to clinical determinations on intellectual impairment from head trauma that were made without knowledge of the patients' pre-injury intellectual level. The statistical significance of the differences between an individual's pre- and post-injury IQ scores, and that of the difference between an individual's post-injury VIQ and PIQ, were determined according to the WAIS-RC Manual.5

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the demographic data and the pre- and post-injury IQ scores of the 17 patients. For five of the patients (cases 1 through 5), their post-injury VIQ, PIQ, and FSIQ were all significantly lower than their corresponding pre-injury scores. Case 6 had significantly lower post-injury VIQ and FSIQ. Cases 7 and 8 had significantly lower post-injury VIQ. However, for cases 1–3, 7, and 8, post-injury VIQ, PIQ, and FSIQ were all above the conventional cutoff score of 70 for intellectual impairment.

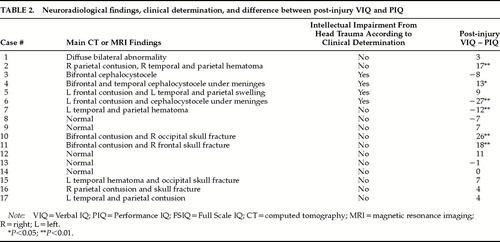

Table 2 summarizes the CT or MRI findings, the conclusion of the conventional clinical evaluation on the presence or absence of intellectual impairment from head trauma, and the difference between the post-injury VIQ and PIQ. Cases 1 through 7, who had significantly lower post-injury IQ scores (see Table 1), all showed neuroradiological evidence of brain damage (see Table 2). However, three of the seven (cases 1, 2, and 7) were judged to have no intellectual impairment from head trauma according to traditional clinical evaluation, which relied mainly on post-injury IQ scores.

Table 2 shows that cases 2, 4, 10, and 11 had significantly higher post-injury VIQ than PIQ, and that their CT or MRI indicated either right-hemisphere damage or bilateral damage. Cases 6 and 7 had lower post-injury VIQ than PIQ, and their CT or MRI indicated left-hemisphere damage. Among these six patients who showed significant differences between their post-injury VIQ and PIQ, three (cases 7, 10, and 11) had FSIQ above 90, and one (Case 2) had FSIQ above 70 (see Table 1).

Table 2 shows that cases 4, 5, and 6 were clinically determined to have suffered intellectual impairment by forensic psychiatrists because their post-injury FSIQ was less than 70. Although Case 3 had an FSIQ of 81, he was also clinically determined to have suffered intellectual impairment because he had a history of superior pre-injury cognitive functioning. On the other hand, five patients (cases 1, 2, 7, 10, and 11) were clinically determined to have not suffered intellectual impairment because their post-injury FSIQs were higher than 70—even though all showed neuroradiological evidence of brain damage (see Table 2). Cases 1, 2, and 7 also showed significant deterioration in IQ scores (see Table 1).

In general, the left hemisphere brain is responsible for verbal function, particularly in the individuals who are right-handed, whereas right hemisphere brain is responsible for performance function. Usually in a normal brain, the difference of VIQ and PIQ (V–Q difference) is less than one standard deviation (15 points). If someone's VIQ–PIQ difference is more than 15 points, he or she may have a certain degree of damage in one hemisphere. Cases 2, 10, and 11 had more serious damage in their right hemisphere, and their PIQ was significantly lower than their VIQ (see Table 2). Cases 6 and 7 had more serious damage in their left hemisphere, and their VIQ was significantly lower than their PIQ (see Table 2). Their psychological results are consistent with the findings of neuroradiological imaging, which indicate that these subjects suffered intellectual damage from their head trauma.

DISCUSSION

To date, there is no gold criterion in China in the fields of psychiatry and neurology for determining intellectual damage. Neuropsychiatrists typically base their clinical determination of intellectual impairment from head trauma on post-injury IQ scores and supplement this information with neuroradiological findings and the severity of clinical features, including the duration of a coma. However, the demarcation score of intellectual deficit is 70 on the Chinese Revised Version of the Wechsler intelligence scale. That is why the Chinese neuropsychiatrists make the diagnosis of intellectual impairment mainly according to the findings of IQ testing. In the present series of 17 patients with head trauma, three (cases 1, 2, and 7) suffered significant intellectual deterioration and had neuroradiological evidence of brain damage. Since their post-injury IQ scores were above the cutoff point of 70 for intellectual impairment, none of them was judged to be intellectually impaired. For these three cases, adding the comparison between their pre- and post-injury IQ scores would have led to more valid conclusions. Only one patient (Case 3) with a post-injury FSIQ above 70 was clinically determined to have suffered intellectual impairment because he had a documented record of superior pre-injury cognitive functioning. Nevertheless, this determination was repeatedly challenged in court because of his above-70 post-injury FSIQ.

On the basis of post-injury IQ scores alone, neuropsychiatrists can err not only by missing significant intellectual deterioration from head trauma for individuals who had high pre-injury intelligence, but also by attributing intellectual impairment from head trauma to individuals who had borderline or impaired pre-injury intelligence but who suffered no further deterioration from head trauma. A comparison between pre- and post-injury IQ scores can help reduce mistakes in both directions.

There are indications that neuroradiological findings are relative and lack specificity, particularly in mild head injury cases where usually they are negative. Neuroradiology is not the gold standard for mild traumatic brain injury, but it may help to establish the degree of brain injury. Therefore, the determination of intelligence impairment from traumatic head injury should combine the subjects' clinical features, social factors, and the results of IQ testing with the neuroradiological evidence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Evelyn Lee Teng, Ph.D., professor in the Department of Neurology at the University of Southern California, for her help in revising this paper.

|

|

1 Kufman AS, Mclean JE, Reynolds CR: Sex, race, residence and education difference on the 11 WAIS-R subsets. J Clin Psychiatry 1988; 44:231–248Google Scholar

2 Barona A, Reynolds CR, Chastain R: A demographically based index of premorbid intelligence for the WAIS-R. J Consult Clin Psychol 1984; 52:885–887Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Sweet JJ, Mmoberg PJ, Tovian SM: Evaluation of Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised premorbid IQ formulas in a clinical population. Psychol Assess: J Consult Clin Psychol 1990; 2:41–44Google Scholar

4 Dai X, Gong Y: An index of premorbid intelligence for WAIS-RC. Bulletin of Hunan Medical University 1993; 18:171–174Google Scholar

5 Gong Y: The manual of Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale Revised in China. Changsha, China, Hunan Medical University Press, 1992Google Scholar

6 Hartlage LC: Clinical aspects and issues in assessing premorbid IQ and cognitive function. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 1997; 12:763–768Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Smith-Seemiller L, Franzen MD, Burgess EJ, et al: Neuropsychologists' practice patterns in assessing premorbid intelligence. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 1997; 12:739–744Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar