Language-Selective Anomia in a Bilingual Patient

SIR: After a stroke, language loss and recovery in bilingual patients can vary considerably.1 There is controversy over the separateness of the two languages in the brain and the mechanisms for accessing their lexicons.1 Reported here is a rare case in which a bilingual person developed an anomia in English, his most familiar language, but not Spanish, his first-learned language.

Case Report

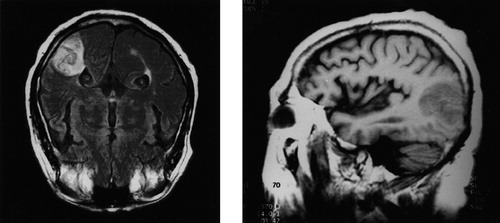

A 71-year-old man had the acute onset of word-finding difficulty in English. The patient was bilingual and spoke Spanish exclusively until age 7, when he began school entirely in English. Prior to entering school he was ambidextrous, but he learned to write with the right hand. Subsequently, his entire education was in English, and this became his strongest language, both at work and at home. He attained an eighth-grade education and was a rancher. He had a history of diabetes mellitus. On initial examination, he had a Wernicke's aphasia in both languages and a right pronator drift with brisk reflexes on the right. The patient was diagnosed with an acute left hemisphere stroke at the junction of the left middle cerebral and posterior cerebral arteries (Figure 1).

Twenty days after his stroke, the patient complained of residual word-finding difficulty in English but not in Spanish. He had resorted to borrowing words from Spanish in order to express himself in English. In conversational speech, Spanish names frequently intruded into his normal English discourse. The patient estimated that prior to his stroke, his fluency in Spanish was fair and in English was excellent. After his stroke, he described his fluency as reversed, that is, better in Spanish than in English.

Examination in English revealed that his comprehension had returned to normal but his speech had circumlocutions and word-finding pauses. His performance on the FAS Controlled Oral Word Fluency Test and the 36-item Token Test was normal.2 He could also describe objects in either language and identify (match-to-sample) their names. On the 60-item Boston Naming Test,2 however, he demonstrated significantly greater spontaneous naming difficulty in English (n=28) as compared to Spanish (n=43; χ2=6.76, P<0.01).

Comment

This case of a patient with “language-selective” anomia in English, but not Spanish, suggests a disassociation of access to the two languages after his lesion in the posterior left temporal region.3 Although the phenomenon is probably dependent on proficiency and age of acquisition, there is evidence that the different language lexicons can be stored separately in the brain.1 One possible mechanism for the patient's language-selective anomia may be an increased interference with English access from simultaneous activation of Spanish. A second potential mechanism is a disproportionate vulnerability of the second language, which is more lexically based, than the first language, which is more conceptually based.4 A final, and more likely, explanation for this patient's language-selective anomia is a differential localization of languages in his hemispheres. In ambidextrous or left-handed individuals who learned a second language along with right-handedness, the original language lexicon may reside predominantly in the right hemisphere and the second language predominantly in the left hemisphere.5

FIGURE 1. Magnetic resonance scans of strokeLeft: T2-weighted horizontal image. Right: T1-weighted sagittal image. A wedge-shaped area of increased signal intensity appears on the T2-weighted image. There is a slightly decreased signal intensity on the T1- weighted image, predominantly involving the left posterior temporal cortex. Both the gray and the underlying white matter are involved.

1 Perani D, Paulesu E, Galles NS, et al: The bilingual brain: proficiency and age of acquisition of the second language. Brain 1998; 121:1841–1852Google Scholar

2 Lezak MD: Neuropsychological Assessment, 3rd edition. New York, Oxford University Press, 1995Google Scholar

3 Benson, DF, Ardila A: Aphasia: A Clinical Perspective. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

4 Aglioti S, Beltramello A, Girardi F, et al: Neurolinguistic and follow-up study of an unusual pattern of recovery from bilingual subcortical aphasia. Brain 1996; 119:1551–1564Google Scholar

5 Daroff RB: Murtagh's case of selective language deficit in a bilingual. Brain Lang 1998; 62:452–454Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar