Low Serum Folate Levels as a Risk Factor for Depressive Mood in Patients With Chronic Epilepsy

Abstract

This study takes into consideration whether low serum folate levels may contribute to depressive mood in patients with chronic epilepsy. The serum folate levels and the score on the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) were examined in 46 patients with chronic epilepsy. Patients with a score indicating at least minor depression on the SDS had a significantly lower serum folate level than patients with a normal score on SDS. There was a significant negative correlation between the serum folate levels and the SDS score. A serum folate level below 7.5 ng/ml was significantly associated with a pathological score on SDS. Because a serum folate level of 7.5 ng/ml is in the normal range for many laboratories, further studies using total plasma homocysteine as a sensitive measure of functional folate deficiency are required to elucidate the impact of folate metabolism on depressive mood in patients with chronic epilepsy.

More than 60% of patients with chronic epilepsy have a history of interictal depressive spectrum disorders.1 An increased number of stressful life events, poor adjustment to seizures, and financial stress have been shown to predict increased depression.2 But the frequency of interictal depression in community-based patients with epilepsy has been found to be greater than in a nonepileptic control population with similar socioeconomic and disability levels.3 This signifies that depression in patients with epilepsy is more than a nonspecific reaction to a chronic disability. Folate deficiency may be a cause of depression4 in psychiatric patients. Patients with epilepsy have a lower folate serum level than control subjects.5 The reduction in serum folate is associated with the induction of enzymes by antiepileptic drugs.6 We investigated in this study whether folate deficiency or even serum folate levels in the lower normal range may contribute to depressive mood in patients with chronic epilepsy.

METHODS

In this study, we examined the data that were obtained in a multimodal therapy-monitoring performed in a specialized epilepsy ward from January 2000 to July 2001. For most of the patients, the indication for ward admission was the need for intensive therapeutic drug monitoring while changing their antiepileptic medication. For patients who were readmitted to our ward during this period, data for only their first visit were included in this study. In patients with interictal “schizophrenia-like” psychosis of epilepsy, a concomitant dysphoric disorder can usually be documented7 that may have another origin than depression in other patients with epilepsy, and therefore we excluded patients with a history of interictal psychosis from the study.

We analyzed the serum folate levels and the score on the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS)8 in 46 patients with chronic epilepsy without a history of interictal psychosis. Patients who were not able to answer the SDS because of reading disability or intellectual disability (IQ<70) were excluded from the study as well.

The serum folate level was obtained as a part of the routine blood investigation on the first morning after admittance. The normal range of folate levels for our laboratory is 3.5 to 16.1 ng/ml. We divided this normal range into three equal parts. Serum folate levels from 3.5 ng/ml to 7.7 ng/ml were considered to be in the low normal range; levels from 7.8 ng/ml to 11.9 ng/ml in the medium normal range; and levels from 12.0 ng/ml to 16.1 ng/ml in the high normal range.

The SDS was administered at the end of a neuropsychological screening battery about two hours later on the same day. On the SDS, a score of more than 50 is considered pathological. Scores between 50 and 60 are taken to suggest minor depression, scores above 70, major depression.9

Statistical analyses were performed with two-tailed t-tests for unrelated samples and with the chi-square test.

RESULTS

On average, the patients were 40.2 years old (SD=12.6); 23 patients were male, 23 female. At the beginning of their epileptic seizures, they were 14.4 years old on the average (SD=13.3). The mean duration of disease was 25.8 years (SD=12.9). The most frequent type of epilepsy was focal symptomatic epilepsy with complex focal seizures (for all epileptologic diagnoses, see Table 1). The frequency of seizures ranged from three generalized tonic-clonic seizures per year to five complex partial seizures per day.

In all, 29 patients (63%) had a score indicating at least minor depression on the SDS. The three most frequent complaints among patients with pathological scores on the SDS were lack of hope, lack of life satisfaction, and difficulty in making decisions.

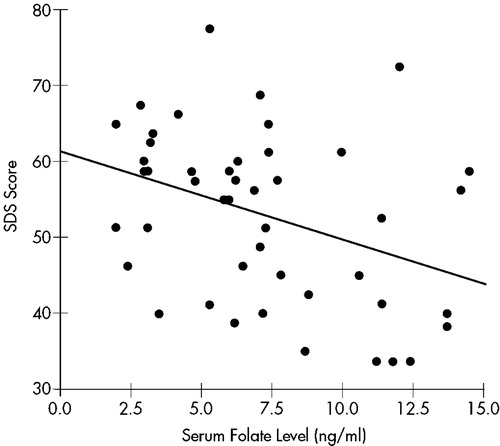

Serum folate level in patients with depressive mood was 6.23 ng/ml (SD=3.36). In patients with a normal SDS score, the serum folate level was 8.72 ng/ml (SD=3.3). This difference was significant (t=2.385, df=29,17, P< 0.05). There was a significant negative correlation between serum folate level and SDS score (r=–0.37; t=–2.64, df=44, P<0.02; see Figure 1). Folate serum level was below the normal range limit of our laboratory in 10 patients (21.7%), of whom 9 (90%) had a pathological score on SDS. Of the remaining 36 patients, 21 had a low normal folate level, 9 a medium normal folate level, and 6 a high folate level. Fifteen (71.4%) of the patients with low normal folate level but only 2 (22.2%) of the patients with medium normal folate level and 3 (50%) of the patients with high normal folate level had a pathological score on the SDS. This association of low normal folate serum levels with pathological scores on SDS was significant (χ2=6.27, df=2, P<0.05).

DISCUSSION

About 60 different variables have been examined in relation to depression in epilepsy.10 Although there is a vast literature on the role of the hippocampus or of temporal lobe lesions in the etiology of interictal depression, the effect of folate deficiency on mood and cognitive functioning has rarely been discussed in the last decade. Nevertheless, 90% of our patients with folate deficiency had a pathological score on the SDS. We found a significant negative correlation between serum folate levels and scores on SDS. However, this correlation was weak, which did not surprise us because all patients were under anticonvulsant medication. Nearly every antiepileptic drug can cause negative or positive psychotropic side effects,11 which may play an important role as confounding factors in our study. Folate deficiency may be caused by alcohol abuse. However, in our sample of patients only three had a history of alcohol addiction and only one of them was still consuming alcoholic drinks, so the influence of alcohol abuse on the results of our study may be small.

Even a serum folate level in the lower third of the normal range seems to be a risk factor for depressive mood in our group of patients. Since this level is higher than the limit of folate deficiency in the normal population, we suppose that patients with chronic epilepsy may have an alteration in the folate metabolism or that their need for folate is underestimated. Seizures may cause a folate deficiency in the brain. In animal experiments, brain folate levels were consistently and significantly lowered after a seizure.12

By use of total plasma homocysteine as a sensitive measure of functional folate deficiency, a biological subgroup of depression has been identified in patients without epilepsy.13 Elevated plasma concentrations of homocysteine have been described in patients under antiepileptic drug treatment,14,15 but no screening for psychiatric morbidity was performed in these studies. Further studies concerning total plasma homocysteine in patients with chronic epilepsy and interictal depressive spectrum disorders are thus needed to elucidate the impact of folate metabolism on depressive mood in patients with chronic epilepsy.

FIGURE 1. Correlation between serum folate level and score on the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS); r=−0.3699.

|

1 Victoroff JI, Benson DF, Engel J Jr, et al: Interictal depression in patients with medically intractable complex partial seizures: electroencephalography and cerebral metabolic correlates (abstract). Ann Neurol 1990; 28:22Google Scholar

2 Hermann BP, Whitman S: Psychosocial predictors of interictal depression. J Epilepsy 1989; 2:231-237Crossref, Google Scholar

3 Mendez MF, Cummings JL, Benson DF: Depression in epilepsy: significance and phenomenology. Arch Neurol 1986; 34:766-770Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Lee S, Chow CC, Shek CC, et al: Folate concentration in Chinese psychiatric outpatients on long-term lithium treatment. J Affect Disord 1992; 24:265-279Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Fröscher W, Maier V, Laage M, et al: Folate deficiency, anticonvulsant drugs, and psychiatric morbidity. Clin Neuropharmacol 1995; 18:165-182Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Kishi T, Fujita N, Eguchi T, et al: Mechanism for reduction of serum folate by antiepileptic drugs during prolonged therapy. J Neurol Sci 1997; 145:109-112Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Blumer D, Wakhlu S, Montouris G, et al: Treatment of the interictal psychoses. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:110-122Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Zung WWK: A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1965; 13:508-515Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Collegium Internationale Psychiatriae Scalarum (ed): Internationale Skalen für Psychiatrie. Göttingen, Beltz Test GmbH, 1996Google Scholar

10 Hermann BP, Seidenberg M, Bell B: Psychiatric comorbidity in chronic epilepsy: identification, consequences, and treatment of major depression. Epilepsia 2000; 41(suppl 2):S31-S41Google Scholar

11 Fröscher W, Möller A, Uhlmann C: Psychischer Befund und neue Antiepileptika. Krankenhauspsychiatrie 1999; 10(suppl 1):S49-S55Google Scholar

12 Smith DB, Obbens EA: Antifolate-antiepileptic relationships, in Folic Acid in Neurology, Psychiatry and Internal Medicine. Edited by Botez MI, Reynolds EH. New York, Raven, 1979, pp 267-283Google Scholar

13 Bottiglieri T, Laundry M, Crellin R, et al: Homocysteine, folate, methylation, and monoamine metabolism in depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000; 69:228-232Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Schwaninger M, Ringleb P, Winter R, et al: Elevated plasma concentrations of homocysteine in antiepileptic drug treatment. Epilepsia 1999; 40:345-350Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Ono H, Sakamoto A, Eguchi T, et al: Plasma total homocysteine concentrations in epileptic patients taking anticonvulsants. Metabolism 1997; 46:959-962Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar