Item-by-Item Factor Analysis of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Symptom Checklist

Abstract

Clinical subtypes of obsessive-compulsive disorder may have differing pathophysiological mechanisms and treatment outcomes. The subtypes identified by the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) Symptom Checklist, clustered by clinical consensus, have never been subject to statistical validation. A factor analysis using a sample of 160 patients with OCD was conducted to determine whether factor analytically derived categories are identical to extant clinically determined categories. Our analysis revealed that the contamination subtype of the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist contains two distinct subgroups: one relating to discomfort and the other to fear of harm. If replicated on a larger scale, the finding of new subtype groupings would have important implications for future research in obsessive-compulsive disorder.

There has been increasing interest in the possibility of discrete subtypes within the umbrella diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). This interest has emerged from different avenues of research. First, phenomenological studies suggest important differences between OCD patients with and without chronic tic disorder.1–4 OCD patients with Tourette's syndrome present with symmetry and aggressive obsessions more commonly than OCD patients without tics, which raises the question of whether the disease process involved in tic disorders is also involved in the production of aggressive and symmetry obsessions. Second, treatment studies have observed that patients with OCD and comorbid tics benefit preferentially from adjunctive dopamine blockers to improve their OCD symptoms.5,6 Furthermore, people who have hoarding rituals generally do not respond to pharmacological treatments and do not respond well to cognitive behavior therapy.7 These observations suggest possible differences in the neurobiology of people who have tic-related OCD and people who hoard. Third, a recent neuroimaging study of OCD subtypes suggests that different parts of the brain may be involved in different manifestations of OCD.8 Patients who were primarily concerned with cleaning and washing had more frontal involvement on positron emission tomography scans, whereas patients who had aggressive, religious, or sexual obsessions had more striatal involvement. In these studies it was assumed that the clinically derived groupings within the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) Symptom Checklist are valid clusterings of the items. To our knowledge, the individual items of the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist have never been subjected to a factor analysis to determine whether the clinically derived groupings also have statistical validity. Given that these subtypes will serve as a major discriminating feature in future neuroimaging and treatment studies of OCD, ensuring their validity is of scientific importance.

In the past decade, researchers and therapists have made tremendous strides in understanding the etiology and treatment of OCD. The research has had several limitations. One is that OCD is represented as a homogeneous disorder, with patients grouped according to symptom severity without consideration of the different subtypes of obsessions and compulsions.9–11 Another limitation lies in the use of symptom inventories that are biased toward specific symptoms12–14 or that fail to include the full range of symptoms.15 A third limitation is the reporting of current clinical symptoms rather than lifetime symptoms of OCD.16,17 Finally, OCD studies often use small study samples as the basis for generalization.12,16,17 Using the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist to identify patient subtypes can help correct several of these methodological problems.

The Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist is a 58-item checklist composed of 16 different subgroups of specific OCD symptoms. The item composition of each of the checklist categories was derived through clinical judgment. The original objectives were to list the full range of OCD symptoms, to group the symptoms into clinically coherent categories, and to create a checklist that would facilitate data collection. Although the Y-BOCS itself has undergone extensive psychometric evaluation, the symptom checklist has not yet been validated statistically (Rasmussen S, personal communication, 1998). Since this instrument is considered the gold standard in the OCD literature, it is of crucial importance to ensure that the clinically derived categories have statistical validity.

A factor analysis of the clinical categories of the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist allows us to determine how the different symptom dimensions of obsessions and compulsions cluster into characteristically similar factors. The factor analysis groups the categories most highly correlated with each other, reducing a large number of variables into a smaller number of factors so that the data may be described and used easily. By creating more parsimonious groupings, we can investigate the heterogeneity of symptoms in OCD and then determine appropriate factor subtypes that might be predictive of treatment outcome.

In this study we addressed two critical questions. The first was whether factor analysis of the clinically derived categories of the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist yields factors similar to those obtained in other studies. An independent replication of prior factor analytic studies is important in demonstrating the similarity of the sample distributions. The second question is whether a factor analysis of individual items of the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist identifies the same clinically derived categories that are described in the instrument.

METHOD

Sample

Our study sample consisted of 160 patients with a diagnosis of OCD. These subjects were enrolled between 1989 and 2000 in three separate studies in our OCD research program at the Anxiety Disorders Clinic at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. OCD diagnosis was based on DSM-III-R and DSM-IV criteria. Patients had to have a minimum Y-BOCS score of 16 for inclusion in any of the three studies. The enrollees included 132 adults and 28 children and adolescents, ranging in age from 9 to 61 years, with a mean age of 30.5 years; 94 (58.8%) were male. The mean baseline Y-BOCS score for the overall sample was 26.4 (SD = 0.90). Two of the studies involved adults with a mean baseline Y-BOCS score of 27.1 (SD = 0.72), and the third involved children and adolescents with a mean baseline score of 23.9 (SD = 1.01). At the time of the baseline administration of the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist, patients had been off medication for at least 2 weeks.

Analysis of the demographic characteristics using the Mann-Whitney U test showed that the clinical subtypes of OCD differed by age and gender. Given that the mean age of the 160 subjects was about 30 years, we evaluated the sample on the basis of those older and those younger than the mean age. The older subjects were more likely than the younger subjects to have hoarding obsessions (P = 0.01). Female subjects were more likely to have symmetry/exactness obsessions (P = 0.04) and counting compulsions (P = 0.05). Male subjects were more likely to have aggressive obsessions (P = 0.03), sexual obsessions (P = 0.02), and repeating rituals (P = 0.02).

Factor Analysis of Clinically Derived Categories

After baseline data from 160 OCD patients were entered into an SPSS database, a principal-components factor analysis with orthogonal rotation was performed on 14 of the 16 a priori clinically derived categories of the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist. The 16 clinically derived categories of the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist include aggressive obsessions, contamination obsessions, sexual obsessions, hoarding obsessions, religious obsessions, obsessions with need for symmetry, exactness, or order, miscellaneous obsessions, somatic obsessions, cleaning/washing compulsions, counting compulsions, checking compulsions, repeating rituals, ordering/arranging compulsions, hoarding compulsions, miscellaneous compulsions, and other compulsions. Based on inclusion and omission of items in previous studies7,16,20 and our own clinical reasoning, we decided to exclude miscellaneous obsessions, miscellaneous compulsions (except the “need to touch” item, which became a category), and the “other” category from the analyses. The impression of our OCD research group was that the items labeled “miscellaneous” or “other” were too ambiguous for the purpose of our factor analysis. However, the “need to touch” item was included as the 14th category in the factor analysis because investigators have expressed particular interest in touching rituals, finding that people who engage in repetitive touching often have counting compulsions as well, and the behavior may be characteristic of a tic disorder.

Taking into account items noted as current, a clinically derived category was coded 1 if at least one item in the category had a check mark—indicating that the subject presented with that symptom—and 0 if none of the items was checked. Rotated component matrices demonstrated how each of the symptom categories clustered. In literature studies, generally a correlation between 0.40 and 0.50 is set as the appropriate cutoff for a symptom category to be included in a factor cluster. We used a conservative value of 0.48 as the cutoff.

Factor Analysis of Individual Items

A principal-components factor analysis with orthogonal rotation was performed on all 38 items included in the 14 categories of the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist to determine whether the a priori clinically derived categories of the instrument were valid. Again, items in the categories of “other,” “miscellaneous obsessions,” and “miscellaneous compulsions” except the “need to touch” item were excluded from the analysis. Items were coded 1 if the subject had the symptom currently and 0 if the subject did not have the symptom currently.

RESULTS

Factor Analysis of Clinically Derived Categories

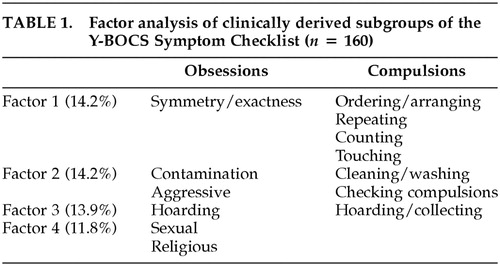

Factor analysis of the clinical categories of the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist grouped those categories most highly correlated with each other, yielding more parsimonious subgroups (Table 1). Catell's scree plot demonstrated that four factors were found to best fit the data, explaining 54.2% of the total variance of observations. Factor 1 grouped together obsessions with the need for symmetry, exactness or order with ordering/arranging compulsions, need to touch, counting compulsions, and repeating rituals. Loadings on this factor ranged from 0.51 to 0.67. Factor 2 correlated aggressive obsessions and contamination obsessions with checking and cleaning/washing compulsions (loadings from 0.52 to 0.82). Factor 3 grouped together hoarding obsessions with hoarding compulsions, with loadings of 0.93 and 0.94. Lastly, factor 4 grouped together religious and sexual obsessions, indicating loadings of 0.67 and 0.70. Since sexual and religious obsessions usually are not accompanied by overt rituals, they often are referred to in the literature as pure obsessions. Somatic obsessions were moderately correlated with religious and sexual obsessions (r = 0.37) but were not included in factor 4 because the chosen cutoff point for factor inclusion was a correlation of 0.48 or higher.

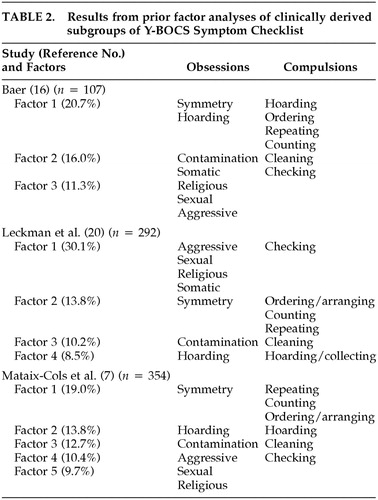

There is considerable overlap between factor clusters of the clinically derived subtypes and factor clusters from prior studies (Table 2).7,16,19 Symmetry obsessions, ordering compulsions, repeating, and counting rituals consistently correlate with one another. Contamination obsessions and washing compulsions continually cluster together. Hoarding obsessions and hoarding compulsions are invariably correlated, and sexual and religious obsessions consistently cluster together. However, checking compulsions and aggressive obsessions have the most variability with regard to how they cluster in each factor analytic study.

Factor Analysis of Individual Items

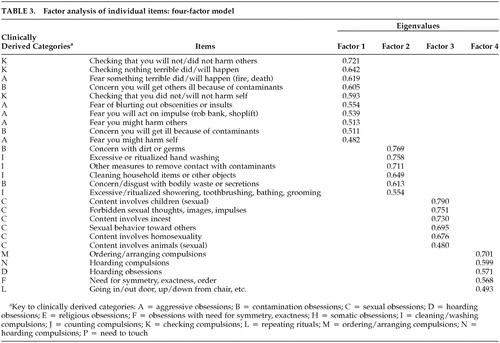

The factor analysis of the individual items of the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist yielded a four-factor model that best explained the overall clinical presentation of OCD symptoms. The scree plot demonstrated that the eigenvalue tapered off at factor 4, with factors 1 through 4 accounting for 39.3% of the variance.

Table 3 demonstrates that many of the clusters of items identified by the rotated factor matrix for the four-factor model overlapped with the clusters proposed by Goodman et al.19 However, there were sufficient differences to consider a new factor structure worthwhile.

The four-factor model yielded the following factor structure: factor 1 was responsibility/harm obsessions and checking; factor 2 was disgust with contaminants/cleaning compulsions; factor 3 was sexual obsessions; and factor 4 was hoarding/symmetry/repeating. Counting compulsions and touching rituals were highly correlated with factor 4, yet were not included in the factor cluster because they just missed the 0.48 cutoff point.

The main finding from this factor analysis was that the items that were originally grouped in the “contamination obsession” subtype of the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist were found to be sorted into two subtypes—one that focuses on disgust with contaminants and one that focuses on the harm associated with contamination. In our factor model, the harm-associated contamination items grouped with items that constituted the “aggression obsession” subtype of the original checklist.

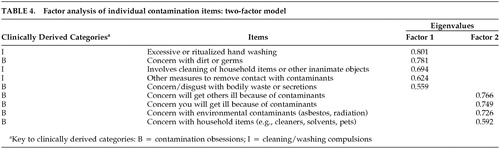

As an additional test of the validity of the results of the statistical partitioning of all 38 items, we conducted a factor analysis on only the nine items in the contamination category. Confirming our finding of heterogeneity within this category, this second factor analysis yielded two separate contamination factors (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

The primary purpose of this study was to investigate the validity of the commonly employed clinical subtypes of OCD as described by the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist. Our first objective was to perform an independent replication of prior factor analytic studies in order to demonstrate similarity in the sample distributions. Our factor analysis of the clinically derived categories of the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist produced four symptom clusters that resembled the clusters in prior factor analytic studies. The second objective was to validate the clinically derived groupings of the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist. A factor analysis was performed on the individual items of the checklist to determine whether the item-by-item analysis would yield the same factor clusters as the clinically derived clusters. Although there was considerable overlap, the results exhibited clinically relevant differences in the content of the factor analytically derived and the clinically derived symptom clusters.

A four-factor model was found to be the best factor structure to demonstrate how obsessive and compulsive symptoms should cluster. Our four-factor model identified the following symptom clusters: responsibility and harm obsessions/checking compulsions; disgust with contaminants/cleaning compulsions; sexual obsessions; and hoarding/symmetry/repeating. Whereas prior factor analytic research in OCD has focused on factor analyses of the clinically derived categories, our study is the first published report to attempt to validate the clustering of symptoms within each category. This is of obvious importance. If the items are not correctly grouped, then research exploring biological or treatment differences among subtypes of OCD patients may yield inaccurate results.

In our item-by-item factor analyses, the Y-BOCS contamination obsessions were split into two clinically homogeneous subgroups. Items such as concerns or disgust with bodily waste or secretions and concern with dirt or germs were found to fall into a separate category (factor 2) from items that involved concern about getting ill and concern about getting others ill (factor 1). Thus, the factor analysis shed light on the fact that people can have two types of contamination concerns: one solely involving a preoccupation with feeling dirty and the other involving a preoccupation with harm as a result of coming in contact with contaminants. This statistical finding supports the clinical observations of Rasmussen and Eisen,18 which indicate that OCD is driven by two motives: fear of harm and reduction of discomfort. In our analysis, the contamination obsessions involving a concern for aversive consequences (i.e., illness) are linked with aggressive obsessions (i.e., fear of harming others, fear that something terrible might happen, and the like) and checking rituals (checking door locks, stoves, appliances; checking that nothing bad happened, and so on). People with these types of obsessions and rituals have an overvalued sense of responsibility, often feeling excessive guilt or responsibility if they are unable to prevent others from getting hurt or ill. They are overly concerned about jeopardizing the safety of others and may become increasingly cautious around contaminants, safety procedures, and the like to avoid being the source of someone else's misfortune. Factor 1, which linked these types of obsessions and rituals, has been labeled “responsibility and harm obsessions.”

The second factor of the four-factor model linked the first two items of the contamination obsession category (disgust with bodily waste or secretions; concern with dirt or germs) with cleaning and washing compulsions. People in this group have a sense of feeling dirty and often engage in excessive or ritualized hand washing, showering, grooming, or toilet routines and may spend hours each day cleaning in order to rid themselves of perceived contaminants.

The third identified factor consisted of the same items that were found to cluster in the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist under the category labeled sexual obsessions and did not cluster with any other items. Although research has previously correlated sexual obsessions with aggressive, religious, and sometimes somatic obsessions, none of the studies performed an item-by-item analysis of the checklist. Thus, this study implies that sexual obsessions can be set apart contextually from other pure obsessions.

Lastly, factor 4 has been labeled “hoarding/symmetry/repeating,” since it groups hoarding obsessions and compulsions, the need for symmetry and exactness, ordering and arranging compulsions, and repeating rituals into one category. Interestingly, these factors have been found to cluster in previous studies and have been linked to chronic tic disorders.1,16 Similar to other studies, this study found counting compulsions and touching rituals to be correlated with factor 4 (loadings of 0.45 and 0.43 respectively), just missing our 0.48 cutoff.

In summary, findings from this study have two main implications. First, the clinically derived subtypes of the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist, in particular the contamination subtype, may mislead researchers who are trying to pinpoint the pathophysiology of different subtypes, because it clumps together two different groups of patients—those who feel dirty and those who fear harm from contamination. If our finding is confirmed with larger data sets, then it would be of considerable importance for future neuroimaging and neurobiological research. Second, our findings may have treatment implications. Although it is well established that OCD patients with tics are less responsive to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, there is little agreement and scarce data on the relevance to outcome of the subtypes of obsessive-compulsive content. Our results, which identify a few significant changes in the clustering of items within the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist may, if replicated in larger studies, help advance the research of OCD.

|

|

|

|

1 George MS, Trimble MR, Ring HA, et al: Obsessions in obsessive-compulsive disorder with and without Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:93-97Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Holzer JC, Goodman WK, McDougle CJ, et al: Obsessive-compulsive disorder with and without a chronic tic disorder: a comparison of symptoms in 70 patients. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 164:469-473Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Leckman JF, Grice DE, Barr LC, et al: Tic-related vs non-tic related obsessive-compulsive disorder. Anxiety 1995; 1:208-215Google Scholar

4 Miguel EC, Coffey BJ, Baer L, et al: Phenomenology of intentional repetitive behaviors in obsessive-compulsive disorder and Tourette's disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:246-255Medline, Google Scholar

5 McDougle CJ, Goodman WK, Leckman JF, et al: Haloperidol addition in fluvoxamine-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with and without tics. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:302-308Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 McDougle CJ, Goodman WK, Price LH, et al: Neuroleptic addition in fluvoxamine-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 147:652-654Google Scholar

7 Mataix-Cols D, Rauch SL, Manzo PA, et al: Use of factor-analyzed symptom dimensions to predict outcome with serotonin reuptake inhibitors and placebo in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999, 156:1409-1416Google Scholar

8 Rauch SL, Dougherty D, Shin LM, et al: Neural correlates of factor-analyzed OCD symptom dimensions: a PET study. CNS Spectr 1998; 3(7):37-43Google Scholar

9 Fals-Stewart W: A dimensional analysis of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Psychol Rep 1992; 70:238-240Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Kim SW, Dysken MW, Pheley AM, et al: The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale: measures of internal consistency. Psychiatry Res 1994; 51:203-211Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 McKay D, Danyko S, Neziroglu F, et al: Factor structure of the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale: a two dimensional measure. Behav Res Ther 1995; 33:865-869Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Hodgson RJ, Rachman S: Obsessional-compulsive complaints. Behav Res Ther 1977; 15:389-395Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Minichiello WE, Baer L, Jenike MA, et al: Age of onset of major subtypes of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord 1990; 4:147-150Crossref, Google Scholar

14 Khanna S, Kalaperumal VG, Channabasavanna SM: Clusters of obsessive-compulsive phenomena in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 156:98-102Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Rettew DC, Swedo SE, Leonard HL, et al: Obsessions and compulsions across time in 79 children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:1050-1056Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Baer L: Factor analysis of symptom subtypes of obsessive compulsive disorder and their relation to personality and tic disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:18-23Google Scholar

17 Baer L, Breiter HC, Goodman WK, et al: Identifying subtypes in obsessive-compulsive disorder and their relationship to Tourette and tic disorder: a factor analytic study. J Abnorm Psychol (in press)Google Scholar

18 Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL: Clinical subtypes in OCD, in Psychobiology. Edited by Zohar Y, Insel TR, Rasmussen SA. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1991Google Scholar

19 Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al: The Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale: I. development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:1006-1011Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Leckman JF, Grice DE, Boardman J, et al: Symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:911-917Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar