Antisocial Violent Offenders With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Demonstrate Akathisia-Like Hyperactivity in Three-Channel Actometry

Abstract

Actometry enables quantitative and qualitative analysis of various hyperactivity disorders. Antisocial violent offenders have demonstrated diurnal increases in motor activity that may be related to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) that often precedes antisocial development. Motor restlessness in ADHD has common features with neuroleptic-induced akathisia. In this study, three-channel actometry was used to compare 15 antisocial violent offenders who had a history of ADHD with 15 healthy control subjects and 10 akathisia patients. The Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (BARS) was used for clinical evaluation of akathisia symptoms. Ankle movement indices and the ankle-waist ratio differentiated the antisocial patients from the healthy controls significantly, with no overlap, and the same parameters expectedly differentiated the akathisia patients from the healthy controls. The repetitive, rhythmic pattern of akathisia was found in 13 of the 15 antisocial patients. Nine of the antisocial patients scored 2 or 3 (mild to moderate akathisia) on the BARS. Thus, the motor hyperactivity of antisocial ADHD patients has common features with mild akathisia. This may be due to a common hypodopaminergic etiology of ADHD and akathisia.

Actometry (or actigraphy) has been used to record motor activity in persons with psychiatric disorders, including mood disorders and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).1 One-channel wrist actometry is commonly used to measure diurnal motor activity patterns. Multiple-channel actometry offers more detailed information about motor activity because it allows movement recording at various locations on the body.

A history of ADHD is commonly found in subjects with antisocial personality disorder (ASP), and ADHD is considered to be one of the precursors of ASP in the presence of conduct disorder.2 Both ASP and ADHD have been studied by actometry. Pervasive increases in diurnal motor activity have been found to distinguish hyperactive boys from controls as effectively as a standardized measure of attention.3 Diurnal actometric recording has revealed an equal hyperactivity in predominantly inattentive and combined ADHD subtypes.4 In a study in which ASP patients demonstrated motor hyperactivity in diurnal one-channel actometric recording,5 the authors discussed this finding as explainable by the common history of ADHD in these patients.

ADHD and neuroleptic-induced akathisia have similar features. Motor restlessness is an essential feature of ADHD, and two items of the diagnostic criteria for ADHD are similar to symptoms of akathisia, namely, fidgeting with the feet while sitting and an inability to remain seated.6 Akathisia is a common adverse effect of antipsychotic drugs, characterized by an inner restlessness, an urge to move with difficulty sitting, and restless movements of the legs. Both akathisia and ADHD are positively correlated with aggressive behavior.7

Three-channel actometry has diagnostic value in neuroleptic-induced akathisia (NIA). It is characterized by a clearly elevated lower limb motor activity during rest and disproportionately high lower limb compared with trunk motor activity, measured as the ratio of ankle to waist movement. Qualitative movement analysis demonstrates a typical movement pattern of periods of rhythmic (0.7–1.6 Hz) motor activity. The prevalence of activity periods increases with time sitting, reflecting decreasing volitional control over the urge to move.8,9 Reports on the movement pattern in NIA are consistent, independent of the recording method.10–12

A dopaminergic deficit seems to be a common etiologic factor for these two hyperkinetic disorders. The hypodopaminergic etiology in ADHD is supported by the therapeutic effect of psychostimulants13 and dopamine-related candidate gene findings,14 whereas the antidopaminergic function behind akathisia has been verified by positron emission tomography.15 Also, serotonergic mechanisms seem to have a role in both ADHD16 and akathisia,17 possibly related to the interaction between serotonergic and dopaminergic systems.

Children with ADHD often have a family history of as well as an increased risk of restless legs syndrome (RLS),18 a movement disorder that has common characteristics with NIA.19 The association between ADHD and RLS may be explained by a common hypodopaminergic etiology or a causal relationship, with RLS-related movement disorders predisposing to ADHD.18,20

In this study we compared motor activity in patients with ASP, with akathisia, and healthy controls. Our hypothesis was that the motor hyperactivity in violent persons with ADHD shares some features with akathisia, such as an inability to sit still and specific lower limb movement episodes while sitting.

METHOD

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Helsinki University Central Hospital. The samples of patients with ASP (n = 15) and akathisia (n = 10) were recruited from the hospital's Department of Psychiatry. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

The ASP sample consisted of consecutive cases of violent offenders undergoing court-ordered mental examination in the hospital's Forensic Psychiatric Department. Subjects between 18 and 65 years of age with a diagnosis of ASP confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)21 were included. Current restless psychiatric conditions were controlled for by the SCID. None of the ASP patients had mania or psychotic disorders, but three of them were diagnosed as having affective or anxiety disorders: one had major depressive disorder, one had major depressive disorder with a comorbid panic disorder, and one had cyclothymia. Exclusion criteria were a current psychotropic medication, a current physical illness, and substance abuse during the previous two months. Abstinence was verified by urine screening. A history of a neurological disorder other than ADHD was also an exclusion criterion. All of the subjects of this sample had a history of ADHD symptoms according to subjective reports, reports of other informants, and childhood records. The symptoms retrospectively fulfilled DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD.

The akathisia sample consisted of neuroleptic-treated inpatients recovering from psychosis. They were recruited to the study by their clinicians, who made the initial diagnosis of NIA and excluded psychotic agitation as to allow the patients to enter the study. The diagnosis of NIA was confirmed by DSM-IV. The subjects of the control sample (n = 15) were employees of the hospital, recruited on voluntary basis. They were physically and mentally healthy, nonmedicated persons. All participants in the study were men. The mean age in the ASP group was 34.3 years (SD 9.9, range 19–49); in the akathisia group, 33.3 years (SD 12.7, range 20–55); and in the control group, 33.8 years (SD 12.7, range 23–56).

We used three-channel actometry instead of the more usual wrist actigraphy because our main interest was lower limb activity and the ankle-waist ratio, which are pathological in some hyperactivity states, such as akathisia and RLS.8,22 Actometers were attached to each subject's waist and ankles. Actometric recording was performed for all subjects during sitting in a standardized clinical interview for 30 minutes, a method that has been described as measuring “controlled rest activity“ in akathisia.8,9 Controlled rest activity is a parameter of motor activity in a situation where sitting is adequate and expected but not instructed or required.

Measuring controlled rest activity has proved useful in diagnosing and monitoring akathisia, enabling both qualitative and quantitative analysis.8,9 Motor activity in controlled rest—during sitting in particular—has demonstrated diagnostic value in other hyperactivity syndromes as well, such as RLS.22 Actometry also enables qualitative analysis of motor activity, yielding findings consistent with electromyography, with akathisia typically in a frequency range of 0.5–3 Hz.8,12

Actometers are small computerized movement detectors that do not affect the wearer's normal movements. The PAM3 monitor (a commercial name that stands for Piezoelectric Activity Monitor, type 3) contains a triaxial piezoelectric accelerometer sensor that reacts to acceleration rates above 0.1 G. Thus, for example, ballistographic movements are too small in amplitude to be detected as acceleration signals by the PAM3 monitor. The recorded acceleration signals produced by body movement are sampled at a rate of 40 Hz, and values of each sample are used to calculate the average activity level within a chosen time window, which was 0.1 seconds in this study. The movement index for the 30 minutes of controlled rest is the sum of values of each time window. Movement indices in this study were calculated by the computerized PAM program of IM Systems (Baltimore, Md.) and divided by 1,000 to allow more convenient handling of the values.

All subjects were evaluated with the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (BARS)23 to determine whether the assumed motor hyperactivity of ASP patients was manifested as akathisia on clinical examination. The Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis test were used to compare the non–normally distributed variables between the groups. The skewness scores of the movement indices were 1.7 for waist measurements, 3.1 for the right ankle, 1.3 for the left ankle, 2.0 for the lower limbs, 1.2 for the ankle-waist ratio, and 1.7 for the laterality index. Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS, version 10.0.

RESULTS

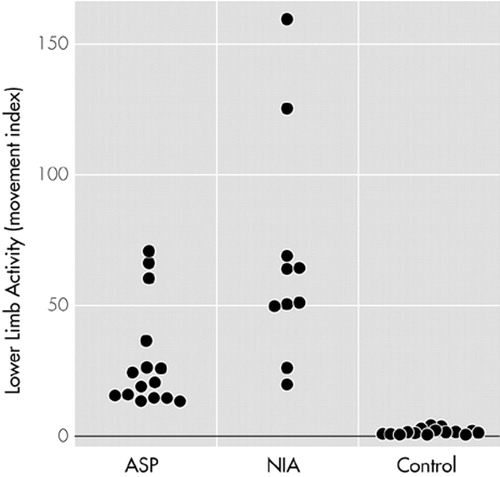

The average controlled rest activity of the ASP sample was clearly higher than the activity of the control sample at all the lower limb movement indices (Table 1). The lower limb activity index of the ASP sample fell in between the control sample and the akathisia sample. As illustrated in Figure 1, the ASP sample's activity index range (13–66) was clearly distinct from that of the control group (0.0015–4), but there was overlap between the ranges of the ASP sample and the akathisia sample (20–160). In spite of this, the difference in lower limb activity between the ASP and akathisia samples was statistically significant (P = 0.004), although the level of significance was lower (P = 0.010) for the left ankle movement index. As expected, there was a significant difference in the ankle movement indices between the akathisia sample and the control sample.

The ankle-waist ratio, reflecting the emphasis of the motor activity on the lower limbs, differentiated the ASP patients significantly from the control subjects (Table 1). As in previous findings, the ankle-waist ratio also differentiated the akathisia patients from the controls. The difference between the ASP and akathisia samples was not significant (P = 0.115), although a trend was noted of akathisia patients having higher ankle-waist ratios, reflecting a more disturbed movement distribution. No significant differences in lateralization were found in pairwise comparisons. When all three groups were compared, significant differences were observed in all movement index parameters except laterality.

The three ASP patients with current affective or anxiety disorders were compared with the other 12 ASP patients. The lower limb activity did not differentiate the two subgroups of ASP patients (median = 23.7, range = 18.3–60.7, compared with median = 17.8, range = 13.0–70.9; P = 0.470); neither did the ankle-waist ratio (P = 0.773) or any other motor activity parameters. When the three ASP patients with affective or anxiety disorders were excluded from the comparison of the ASP sample to the control group, the significant differences between the groups remained unchanged.

Qualitative analysis of the actometric raw data revealed similarities between the ASP and akathisia samples: 13 of the 15 ASP patients demonstrated regular rhythmic activity periods of 0.85–1.80 Hz (mean = 1.2 Hz, SD = 0.3), indistinguishable from the akathisia pattern mentioned earlier. The frequency range of rhythmic activity in the akathisia sample (range = 0.65–1.7 Hz, mean = 1.1 Hz, SD = 0.33) was almost identical to that of the ASP sample. The healthy controls demonstrated no such pattern. ASP patients demonstrated more movement episodes at the end of the controlled rest period, similar to akathisia patients. Unlike the akathisia patients, the ASP patients demonstrated a considerable proportion of irregular motor hyperactivity among the akathisia-like, regular, rhythmic activity periods.

Clinically, no qualitative difference in the restless movements between the ASP and akathisia groups was observed. Both groups demonstrated episodic, small-amplitude, jerky movements of the feet consisting of heel tapping on the floor and foot shaking when the legs were crossed. The restless movements increased toward the end of the 30-minute controlled rest period. The subjects seemed to be unaware of their repetitive, monotonic movements. The restless movements were limited to lower limbs, and they had no bizarre features. All the subjects remained seated during the controlled rest period, although all the akathisia patients and the majority of the ASP patients reported an urge to move.

The mean BARS score for the ASP group was 1.5 (SD = 0.9, range = 0–3). Nine of the ASP patients scored 2 (mild akathisia) or more on the BARS and would have fulfilled DSM-IV criteria for NIA, excluding neuroleptic exposure. Three patients in the ASP group scored 1 (questionable akathisia) on the BARS, and another three scored 0, indicating no signs of akathisia in the clinical evaluation. However, two of these three demonstrated elevations in lower limb activity and a rhythmic akathisia-like pattern in actometry. In the akathisia group, the mean BARS score was 2.9 (SD = 0.9, range = 2–4). All the healthy controls scored 0 on the BARS.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study was that antisocial violent offenders with ADHD and patients with akathisia demonstrated quite similar objectively measured motor hyperactivity compared with a control sample during a controlled rest situation. Motor activity of the lower limbs differentiated the two patient samples from the control sample. The emphasis of the hyperactivity was in the lower limbs compared with the trunk, as measured by the ankle-waist ratio, in both patient samples. Motor activity in the ASP sample was lower than in the akathisia sample, but the difference was nonsignificant for the ankle-waist ratio, which is typically elevated in akathisia.8 A majority of the ASP patients demonstrated clinical akathisia symptoms on the BARS and a typical akathisia pattern in qualitative actometric analysis.

Motor hyperactivity among ASP patients seems to have several features in common with the hyperactivity of akathisia patients: a significantly increased controlled rest activity; an emphasis on hyperactivity of the lower limbs; repetitive, rhythmic movement episodes of the same frequencies; and a predominating tendency for the movement episodes to occur at the end of the controlled rest period, indicating an intensifying urge to move or a diminishing of the initial ability to suppress the movements. The qualitative and the quantitative differences of the restless movements between akathisia and ASP patients are better demonstrated by actometry than by simple observation in a clinical evaluation.

The results support our hypothesis concerning the nature of the hyperactivity in ASP with ADHD, which is characterized by an inability to sit still and the occurrence of specific lower limb movement episodes. The akathisia-like hyperactivity findings in the ASP patients are probably explained by ADHD, an assumed precursor of ASP.2 All of the ASP patients in our sample had a history of childhood ADHD, and most of them had residual ADHD symptoms. The clinical and actometric overlapping of ASP hyperactivity and NIA motor symptoms further supports the hypothesis of a common hypodopaminergic etiology. Considering the obvious co-occurrence of ADHD and RLS symptoms,18 it is questionable whether the akathisia-like findings in our ASP sample are related to RLS rather than to akathisia. Discriminating between RLS and akathisia is not a simple process, because these two movement disorders are clinically overlapping and are often intermixed in the literature.24 The actometric movement pattern detected in RLS,25 however, is different from the typical NIA pattern found in both of our patient samples.

The rhythmic (approximately 1.2 Hz) movement episodes in ASP with ADHD may reflect a motor response to inner restlessness and discomfort aroused by sitting still, as in NIA; or they may reflect idiopathic akathisia, possibly related to hypodopaminergia in ADHD; or they may merely be motor symptoms of ADHD unrelated to akathisia despite the obvious similarity. The appearance of the NIA pattern and the increased movement indices in the ASP group are not likely to be explained by any psychopathology other than ADHD, because current drug abusers were excluded and only three ASP patients were diagnosed as having current affective or anxiety disorders. Their movement indices showed no significant differences in comparison with those of other ASP patients.

This study reproduced our previous actometric findings in akathisia;8 the average values in this study were similar though slightly lower than in the previous study (ankle movement index = 69.1 vs. 76.4 in the previous study). Akathisia is a distressing state requiring immediate care, and it has been related to suicide and violence. Adequate treatment of akathisia entails reducing or changing the causative antipsychotic medication. When this is not possible or sufficient, other pharmacological interventions are recommended, among which serotonin-2 blocking and antiadrenergic agents may be of interest in treating ASP patients with ADHD. Aggression related to ADHD seems to respond to propranolol, a β-blocking agent commonly used in the treatment of akathisia.26 Further research is needed to determine whether hyperactivity and even aggressivity related to ADHD in ASP might be relieved by these interventions.

|

FIGURE 1. Lower limb motor activity as indicated by movement indices in study subjects in the antisocial personality disorder group (ASP), the akathisia group (NIA), and the control group, measured by three-channel actometry during controlled rest. Each circle represents a study subject.

1 Teicher MH: Actigraphy and motion analysis: new tools for psychiatry. Harvard Rev Psychiatry 1995; 3:18-35Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 McCracken JT, Smalley SL, McGough JJ, et al: Evidence for linkage of tandem duplication polymorphism upstream of the dopamine D4 receptor gene (DRD4) with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Mol Psychiatry 2000; 5:531-536Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Porrino LJ, Rapoport J, Behar D, et al: A naturalistic assessment of the motor activity of hyperactive boys. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1983; 40:681-687Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Dane AV, Schachar RJ, Tannock R: Does actigraphy differentiate ADHD subtypes in a clinical research setting? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:752-760Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Virkkunen M, Rawlings R, Tokola R, et al: CSF biochemistries, glucose metabolism, and diurnal activity rhythms in alcoholic, violent offenders, firesetters, and healthy controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:20-27Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

7 Ratey J, Gordon A: The psychopharmacology of aggression: toward a new day. Psychopharmacol Bull 1993; 29:65-73Medline, Google Scholar

8 Tuisku K, Lauerma H, Holi M, et al: Measuring neuroleptic-induced akathisia by three-channel actometry. Schizophrenia Res 1999; 40:105-110Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Tuisku K, Lauerma H, Holi M, et al: Akathisia masked by hypokinesia. Pharmacopsychiatry 2000; 33:147-149Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Braude WM, Charles IP, Barnes TR: Coarse, jerky foot tremor: tremographic investigation of an objective sign of acute akathisia. Psychopharmacology 1984; 82(1-2):95-101Google Scholar

11 Rapoport A, Stein D, Grinshpoon A, et al: Akathisia and pseudoakathisia: clinical observations and accelerometric recordings. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:473-477Medline, Google Scholar

12 Cunningham SL, Winkelman JW, Dorsey CM, et al: An electromyographic marker for neuroleptic-induced akathisia: preliminary measures of sensitivity and specificity. Clin Neuropharmacol 1996; 19:321-332Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Seeman P, Madras BK: Anti-hyperactivity medication: methylphenidate and amphetamine. Mol Psychiatry 1998; 3:386-396Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Thapar A, Holmes J, Poulton K, et al: Genetic basis of attention deficit and hyperactivity. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174:105-111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Farde L, Nordström AL, Wiesel FA, et al: Positron emission tomographic analysis of central D1 and D2 dopamine receptor occupancy in patients treated with classical neuroleptics and clozapine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:538-544Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Quist J, Kennedy J: Genetics of childhood disorders: XXIII. ADHD, part 7: the serotonin system. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:253-256Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Poyurovsky M, Shardorovsky M, Fuchs C, et al: Treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia with the 5-HT2 antagonist mianserin: double-blind, controlled study. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174:238-242Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Picchietti DL, Underwood DJ, Farris WA, et al: Further studies on periodic limb movement disorder and restless legs syndrome in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mov Disord 1999; 14:1000-1007Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Walters AS, Hening W, Rubinstein M, et al: A clinical and polysomnographic comparison of neuroleptic-induced akathisia and the idiopathic restless legs syndrome. Sleep 1991; 14:339-345Medline, Google Scholar

20 Walters AS, Mandelbaum DE, Lewin DS, et al: Dopaminergic therapy in children with restless legs/periodic limb movements in sleep and ADHD. Dopaminergic Therapy Study Group. Ped Neurology 2000; 22:182-186Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 First MB, Gibbon M , Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Benjamin L.: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) Users' Guide. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., 1997Google Scholar

22 Montplaisir J, Boucher S, Nicolas A, et al: Immobilization tests and periodic leg movements in sleep for the diagnosis of restless leg syndrome. Mov Disord 1998; 13:324-329Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Barnes TRE: A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 154:672-676Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Sachdev P: The development of the concept of akathisia: a historical overview. Schizophrenia Res 1995; 16:33-45Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Kazenwadel J, Pollmacher T, Trenkwalder C, et al: New actigraphic assessment method for periodic leg movements. Sleep 1995; 18:689-697Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Mattes JA: Comparative effectiveness of carbamazepine and propranolol for rage outbursts. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosciences 1990; 2:159-164Link, Google Scholar