Regularly Occurring Periods of Eye Motility, and Concomitant Phenomena, During Sleep

Reprinted (abstracted/excerpted) with permission from E. Aserinsky and N. Kleitman, Science 118:273–274 (1953). Copyright 1953 American Association for the Advancement of Science. Introduction copyright © 2003 American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

Slow, rolling or pendular eye movements such as have been observed in sleeping children or adults by Pietrusky,1 De Toni,2 Fuchs and Wu,3 and Andreev,4 and in sleep and anesthesia by Burford5 have also been noted by us. However, this report deals with a different type of eye movement-rapid, jerky, and binocularly symmetrical-which was briefly described elsewhere.6

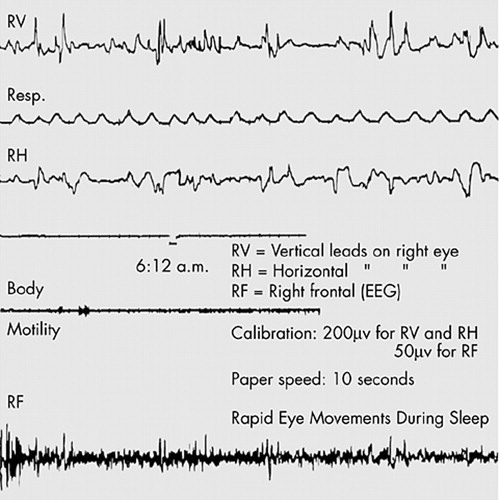

The eye movements were recorded quantitatively as electrooculograms by employing one pair of leads on the superior and inferior orbital ridges of one eye to detect changes of the corneo-retinal potential in a vertical plane, and another pair of leads on the internal and external canthi of the same eye to pick up mainly the horizontal component of eye movement. The potentials were led into a Grass Electroencephalograph with the EOGa channels set at the longest time constant. Brain waves, lid and jaw muscle activity and electrode movement introduced superfluous potentials which severely hindered the identification of eye movement potentials. To eliminate this difficulty, a monopolar recording was made simultaneously from the frontal area (and occasionally from the anterior temporal area) to be compared with the bipolarly recorded electrooculogram. In this way, the eye movement potential could be recognized easily as a wave in phase on the monopolar and bipolar recordings, but with a potential from 2 to 4 times greater on the latter recording. Note that the gain settings (Fig. 1) for the bipolar recording (RV) and monopolar recording (RF) were adjusted so that an equal excursion of both pens signified that the bipolar potential was actually 4 times greater than the monopolar potential. The criterion for identification of eye movement was confirmed by direct observation of several subjects under both weak and gradually intensified illumination. Under the latter condition, motion pictures were taken of 2 subjects without awakening them, thereby further confirming the validity of our recording method and also the synchronicity of eye movements.

Twenty normal adult subjects were employed in several series of experiments although not all the subjects were involved in each series. To confirm the conjecture that this particular eye activity was associated with dreaming, 10 sleeping individuals in 14 experiments were awakened and interrogated during the occurrence of this eye motility and also after a period of at least 30 min to 3 hr of ocular quiescence. The period of ocular inactivity was selected on the basis of the EEG pattern to represent, as closely as possible, a depth of sleep comparable to that present during ocular motility. Of 27 interrogations during ocular motility, 20 revealed detailed dreams usually involving visual imagery; the replies to the remaining 7 queries included complete failure of recall, or else, “the feeling of having dreamed,” but with inability to recollect any detail of the dream. Of 23 interrogations during ocular inactivity, 19 disclosed complete failure of recall, while the remaining 4 were evenly divided into the other 2 categories. Recognizing the inadequacies of employing a x2 test for the independence of the 2 groups of interrogations, the probability nevertheless on a x2 basis is that the ability to recall dreams is significantly associated with the presence of the eye movements noted, with a p value of less than 0.01.

Eleven subjects in one series of 16 experiments were permitted to sleep uninterruptedly throughout the night. The mean duration of sleep was 7 hr. The first appearance of a pattern of rapid, jerky eye movements was from 1 hr 40 min to 4 hr 50 min (3 hr 14 min, mean) after going to bed. This pattern of eye motility was of variable duration and frequently disappeared for a fraction of a minute or for several minutes only to reappear and disappear a number of times. The period from the onset of the first recognizable pattern to the disappearance of the last pattern was from 6 to 53 min with a mean of 20 min. A second period of eye movement patterns appeared from 1 hr 10 min to 3 hr 50 min (2 hr 16 min, mean) after the onset of the first eye motility period. With lengthier sleep there occurred a third and, rarely, a fourth such period. The electrooculogram disclosed vivid potentials with amplitudes as high as 300-400 μv, each potential lasting about 1 sec. This was further striking in comparison with simultaneously recorded monopolar EEG's, from the frontal and occipital areas, which were invariably of low amplitude (5-30 μv) and irregular frequency (15-20/sec and 5-8/sec predominating).

In another series of experiments involving 14 subjects, the respiratory rate was calculated for a minimum of 1/2 min during eye motility and compared with the rate for a similar duration 15 min before and after an eye motility period. The respiratory rate had mean of 16.9/min during eye motility in contrast with 13.4/min during ocular quiescence. By using Fisher's t method, the difference in rates was found to be statistically significant with a probability of less than 0.001. Experiments now in progress suggest that heart rate also is probably higher in the presence of these eye movements. Body motility records were secured in 6 experiments by attaching a sensitive crystal to the bed spring and leading the output through a resistance to a Grass preamplifier. In every case the eye motility periods were associated with peaks of overt bodily activity although the latter were frequently present in the absence of eye movements.

Data obtained from the 2 female subjects used in these experiments were at least qualitatively similar to that obtained from males.

The fact that these eye movements, EEG pattern, and autonomic nervous system activity are significantly related and do not occur randomly suggests that these physiological phenomena, and probably dreaming, are very likely all manifestations of a particular level of cortical activity which is encountered normally during sleep. An eye movement period first appears about 3 hr after going to sleep, recurs 2 hr later, and then emerges at somewhat closer intervals a third or fourth time shortly prior to awakening. This method furnished the means of determining the incidence and duration of periods of dreaming.

Manuscript received April 3, 1953.

FIGURE 1. Sample record exhibiting rapid eye movements in a sleeping subject.

RV = vertical leads on right eyes, RH = horizontal leads on right eye, RF = right frontal (EEG). (Calibration: 200 μv for RV and RH, 50μv for RF; paper speed:10 sec)

1Aided by a grant from the Wallace C. and Clara A. Abbott Memorial Fund of the University of Chicago.

1 Pietrusky, F. Klin Monatsbl. f. Augenheilkunde., 68, 355 (1922).Google Scholar

2 De Toni, G. Pediatria, 41, 488 (1933).Google Scholar

3 Fuchs, A., and Wu, F.C. Am. J. Ophthalmol., 31, 717 (1948).Google Scholar

4 Andreev, B.V. Fiziol. Zhor. SSR, 36, 429 (1950).Google Scholar

5 Burford, G.E. Anesth. & Analgesia, 20, 191 (1941).Google Scholar

6 Aserinsky, E., and Kleitman, N. Federation Proc., 12, 6 (1953).Google Scholar