The Limbic Thalamus

The thalamus has been referred to as the “Grand Central Station” of the brain because virtually all incoming information relays through it en route to the cortex. In turn, virtually all areas of the cortex project to divisions of the thalamus. Thus, knowledge of thalamic anatomy and connections is critical in understanding thalamic influence on cortical function and in the interpretation of functional brain imaging studies. The multiple systems for naming the divisions of the thalamus make the literature challenging.1,2 In addition, the illustrations used in traditional texts do not easily translate into the format of clinical imaging reports. The purpose of this paper is to bypass these obstacles by summarizing and synthesizing the complex functional anatomy of the portions of the human thalamus related to memory, emotion, and arousal. Color-coding is used to facilitate identification of the relevant nuclei and their connections. Clinical images are provided to assist in translating the anatomical knowledge to the bedside.

This communication is intended as a general guide, since both the connections and the functions of these nuclei are not completely understood. While some clinically based tracing of connections has been done, most of what is known comes from experimental studies. To assure the closest possible match to human functional anatomy, only the results from human and primate studies have been used in this synthesis. In the future, imaging techniques that allow functional anatomy to be studied in vivo in humans will provide the data needed to further refine these maps. In particular, the advent of much higher resolution magnetic resonance imaging will make fine mapping of pathway degeneration possible.3 Diffusion tensor imaging also shows promise for both pathway tracing and perhaps identification of individual thalamic nuclei in vivo.1,4 It is clear that the size and boundaries of both cortical projection areas and thalamic nuclei vary across individuals.2,5,6 Detailed studies that will eventually provide probabilistic maps of cortical functional divisions (i.e., Brodmann areas) are underway.2

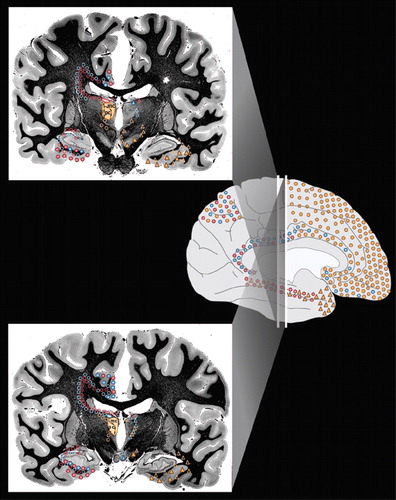

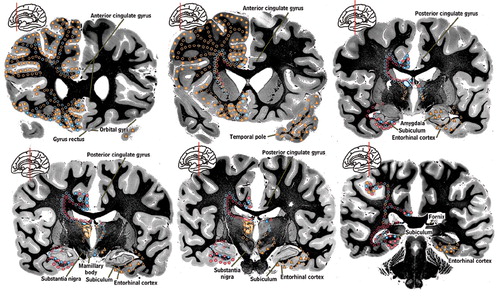

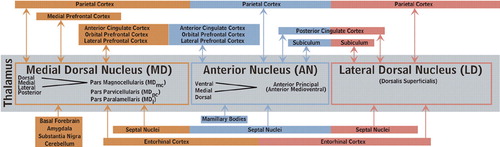

Thalamic nuclei that are generally agreed to be involved in memory, emotion, and arousal are filled with color on the left side of the coronal brain sections in Figure 1a and Figure 1b. They are the medial dorsal nucleus (orange), the anterior nucleus (blue), and the lateral dorsal nucleus (pink).7,8 These nuclei have intimate interconnections with cortical and subcortical areas (indicated by colored symbols on the coronal brain sections in Figure 1a) that are considered part of the limbic system of the brain and deemed the “limbic thalamus.”9 They have also been termed the “visceral thalamus” because they are vital for maintenance of circadian rhythms and for the generation of normal sleep patterns. Some authors also include the midline, intralaminar, and medial pulvinar nuclei in the “limbic thalamus” because of their projections to the cingulate cortex.10–13

The nomenclature, nuclear divisions, and subdivisions of the thalamus vary among medical specialties, a potential source of confusion when reading the literature of different fields. Two commonly used systems are summarized within the circuit diagram in Figure 1b. Recognition of the various internal divisions of thalamic nuclei is increasingly important. The tracing of circuits within the brain has progressed to the point that function can be attributed, at least on a tentative basis, at this finer level of localization.14,15 A summary of the major connections of these nuclei are color-coded onto surface drawings of the cortex (see Cover) and images of coronal myelin-stained brain slices (Figure 1a). Connections within both the left and right hemisphere are thought to be very similar. Connections with brainstem nuclei are not included as they are not currently thought to be specifically involved in limbic function.

Medial Dorsal Nucleus (MD)

Medial dorsal nucleus has major reciprocal connections with orbital, medial prefrontal, lateral prefrontal, and anterior cingulate cortices.10,11,16–30 Reciprocal connections with supplementary motor and parietal cortices as well as the frontal eye fields have also been reported.10,11,18–21,26–28 It receives input from temporal polar, entorhinal and primary olfactory cortices as well as much of the basal forebrain. This includes the septal nuclei, ventral pallidum, nucleus basalis of Meynert, and diagonal band of Broca.10,16,20,24,25,31–38 The amygdala, substantia nigra, and cerebellum also project to MD.19,20,24,36,38–42 These connections and the effects of injury to this region indicate a role in memory (perhaps specifically in retrieval of episodic memory), mood, motivation and the sleep/waking cycle. It has been proposed that the connections of the MD segregate into at least three major functional circuits.14,15,43 The dorsal portion of the magnocellular part of MD (MDmc) has reciprocal connections with anterior cingulate cortex and is involved in motivation. The ventral portion of MDmc has reciprocal connections with orbitofrontal cortex and is involved in inhibition of inappropriate behavior. The parvicellular portion of MD (MDpv) has reciprocal connections with dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and is involved in mediation of executive functions.

Anterior Nucleus (AN)

Anterior nucleus has major reciprocal connections with anterior and posterior cingulate cortices and the subiculum-presubiculum portion of the hippocampal complex.9–11,16,18,25,28,34,44–48 Lesser connections with orbital frontal, dorsolateral prefrontal, and parietal cortices have also been reported.10,18,26–28,30,34,39,45,46,49 AN also receives major input from the mamillary complex.8,50 It may also receive a projection from the septal nuclei.16,36 These connections and the effects of injury to this region indicate a role in memory, modulation of the sleep/waking cycle, and directed attention.

Lateral Dorsal Nucleus (LD)

Lateral dorsal nucleus has major reciprocal connections with posterior cingulate and parietal cortices as well as the subiculum-presubiculum and entorhinal cortex portions of the hippocampal complex.8,10,11,26,27,34,48–52 It may also receive a projection from the septal nuclei.16,36 A role in integration of motivation and/or attention with sensory processes has been suggested.10,53

Pathology

A common source of injury to the thalamus is vascular insult. Most vascular lesions are fairly large, affecting all or part of multiple nuclei as well as associated tracts. As a result, there is a great deal of overlap in symptoms related to infarction or hemorrhage from a particular artery that can serve the anterior and medial thalamus.54–58 Injury to the left is associated with deficits in language, verbal intellect and verbal memory. Right-sided injury is associated with deficits in visuospatial and nonverbal intellect and visual memory as well as delirium. Medial thalamus appears to be particularly important for temporal aspects of memory. Bilateral injury is associated with severe memory impairment (thalamic amnesia) as well as dementia. Some researchers attribute the memory deficits to destruction of the tracts connecting limbic structures to AN and MD (mamillothalamic tract, amygdalofugal tract). Injury to the anterior and medial thalamus can also result in disturbances of autonomic functions, mood, and the sleep/waking cycle.59,60 Symptoms usually lessen with time, but commonly significant impairment remains.

The limbic areas of thalamus are vulnerable to nonvascular insults. Korsakoff's syndrome results from thiamine deficiency (often as a result of alcoholism). It is characterized by both anterograde and retrograde amnesia, particularly for recent events, and confusion (acutely). These symptoms have been attributed variously to involvement of the mamillary bodies, MD and AN.3,61–63 Fatal Family Insomnia is a prion disease characterized by severe neuronal degeneration in AN and MD.64 Pathways are not affected. This degeneration is not visible on either computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, but is associated with anterior thalamic hypometabolism in some cases.65,66 There may also be widespread cortical hypometabolism. Clinically there is progressive impairment of the sleep-waking cycle progressing to total loss of sleep as well as autonomic dysfunction and gradual loss of hormonal circadian rhythms.67,68 Prior to death the patient becomes stuporous. The clinical features may be a direct result of neuronal injury in AN and MD or may result from disconnection of the hypothalamus, limbic, and prefrontal cortices.68

Conclusion

The functional anatomy of the thalamus is both complicated and clinically important because multiple types of information pass through it on the way to the cortex. Thus, injury or dysfunction within the thalamus can alter functioning of other areas, as shown by remote alterations in cerebral blood flow and metabolism.69–76 Conversely, injury remote from the thalamus can cause thalamic dysfunction or degeneration.77–80 Knowledge of the functional anatomy of the thalamus should prove useful in evaluating diminished cortical functions caused by thalamic lesions. This includes, but is not limited to, patients undergoing functional imaging. It will promote understanding of thalamic lesions and hypometabolism caused by anterograde and/or retrograde degeneration following cortical injury. Additionally, it will aid in the detection of radiographically subtle, clinically significant lesions; in the planning of rehabilitation and psychiatric treatment; and in the planning of magnetic resonance imaging-guided thalamic surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the Mike Hogg Fund to Dr. Taber. The authors thank Archibald J. Fobbs, Jr., B.S., curator of the National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, D.C., for providing the myelin-stained coronal brain slices.

Cover The principal cortical and subcortical connections of the medial dorsal (orange), anterior (blue) and lateral dorsal (pink) nuclei of the thalamus are color-coded onto medial, lateral and inferior views of the cortical surface (Cover), onto images of coronal myelin-stained brain slices (Cover and below) and summarized into a color-coded circuit diagram (below). Reciprocal connections are indicated by color-coded circles. Afferents are indicated by color-coded triangles. The approximate location of fibers of passage are indicated by open symbols. Each thalamic nucleus is filled with the appropriate color on the left side of brain slices. Subdivisions and usual abbreviations for each nucleus are summarized in the circuit diagram. Some anatomic structures are labeled for orientation.

Figure 1a. The principal cortical and subcortical connections of the medial dorsal (orange), anterior (blue) and lateral dorsal (pink) nuclei of the thalamus are color-coded onto medial, lateral and inferior views of the cortical surface (Cover), onto images of coronal myelin-stained brain slices (Cover and below) and summarized into a color-coded circuit diagram (below). Reciprocal connections are indicated by color-coded circles. Afferents are indicated by color-coded triangles. The approximate location of fibers of passage are indicated by open symbols. Each thalamic nucleus is filled with the appropriate color on the left side of brain slices. Subdivisions and usual abbreviations for each nucleus are summarized in the circuit diagram. Some anatomic structures are labeled for orientation.

Figure 1b. The principal cortical and subcortical connections of the medial dorsal (orange), anterior (blue) and lateral dorsal (pink) nuclei of the thalamus are color-coded onto medial, lateral and inferior views of the cortical surface (Cover), onto images of coronal myelin-stained brain slices (Cover and below) and summarized into a color-coded circuit diagram (below). Reciprocal connections are indicated by color-coded circles. Afferents are indicated by color-coded triangles. The approximate location of fibers of passage are indicated by open symbols. Each thalamic nucleus is filled with the appropriate color on the left side of brain slices. Subdivisions and usual abbreviations for each nucleus are summarized in the circuit diagram. Some anatomic structures are labeled for orientation.

1 Wiegell MR, Tuch DS, Larsson HB et al.: Automatic segmentation of thalamic nuclei from diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage 2003; 19:391–401Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Amunts K, Schleicher A, Burgel U et al.: Broca's region revisited: cytoarchitecture and intersubject variability. J Comp Neurol 1999; 412:319–341Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Yamada K, Shrier D, Rubio A et al.: MR imaging of the mamillothalamic tract. Radiology 1998; 207:593–598Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Taber KH, Pierpaoli C, Rose SE et al.: The future for diffusion tensor imaging in neuropsychiatry. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2002; 14:1–5Link, Google Scholar

5 Rajkowska G, Goldman-Rakic PS: Cytoarchitectonic definition of prefrontal areas in the normal human cortex: II. Variability in locations of areas 9 and 46 and relationship to the Talairach Coordinate System. Cereb Cortex 1995; 5:323–337Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Uylings HB, Sanz Arigita E, de Vos K et al.: The importance of a human 3D database and atlas for studies of prefrontal and thalamic functions. Prog Brain Res 2000; 126:357–368Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Armstrong E: Limbic thalamus: anterior and mediodorsal nuclei, in The Human Nervous System. Edited by Paxinos G. San Diego, Academic Press, 1990, 469–481Google Scholar

8 Bentivoglio M, Kultas-Ilinsky K, Ilinsky I: Limbic thalamus: structure, intrinsic organization, and connections, in Neurobiology of Cingulate Cortex and Limbic Thalamus: A Comprehensive Handbook. Edited by Vogt BA, Gabriel M. Boston, Birkhauser, 1993, 71–122Google Scholar

9 Yakovlev PI, Locke S, Koskoff DY et al.: Limbic nuclei of thalamus and connections of limbic cortex. Arch Neurology 1960; 3:620–641Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Yeterian EH, Pandya DN: Corticothalamic connections of paralimbic regions in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol 1988; 269:130–146Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Vogt BA, Pandya DN, Rosene DL: Cingulate cortex of the rhesus monkey: I. Cytoarchitecture and thalamic afferents. J Comp Neurol 1987; 262:256–270Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Schmahmann JD, Pandya DN: Anatomic investigation of projections from thalamus to posterior parietal cortex in the rhesus monkey: a WGA-HRP and fluorescent tracer study. J Comp Neurol 1990; 295:299–326Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Van der Werf YD, Witter MP, Groenewegen HJ: The intralaminar and midline nuclei of the thalamus. Anatomical and functional evidence for participation in processes of arousal and awareness. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 2002; 39:107–140Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Mega MS, Cummings JL, Salloway S et al.: The limbic system: an anatomic, phylogenetic, and clinical perspective [see comments]. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1997; 9:315–330Link, Google Scholar

15 Burruss JW, Hurley RA, Taber KH et al.: Functional neuroanatomy of the frontal lobe circuits. Radiology 2000; 214:227–230Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Powell EW: Limbic projections to the thalamus. Exp Brain Res 1973; 17:394–401Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 Tanaka DJ: Thalamic projections of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). Brain Res 1976; 110:21–38Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Goldman-Rakic PS, Porrino LJ: The primate mediodorsal (MD) nucleus and its projection to the frontal lobe. J Comp Neurol 1985; 242:535–560Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Ilinsky IA, Jouandet ML, Goldman-Rakic PS: Organization of the nigrothalamocortical system in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol 1985; 236:315–330Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Russchen FT, Amaral DG, Price JL: The afferent input to the magnocellular division of the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus in the monkey, Macaca fascicularis. J Comp Neurol 1987; 256:175–210Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Giguere M, Goldman-Rakic PS: Mediodorsal nucleus: areal, laminar, and tangential distribution of afferents and efferents in the frontal lobe of rhesus monkeys. J Comp Neurol 1988; 277:195–213Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Barbas H, Henion TH, Dermon CR: Diverse thalamic projections to the prefrontal cortex in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol 1991; 313:65–94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Siwek DF, Pandya DN: Prefrontal projections to the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol 1991; 312:509–524Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Ray JP, Price JL: The organization of projections from the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus to orbital and medial prefrontal cortex in macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol 1993; 337:1–31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Bachevalier J, Meunier M, Lu MX et al.: Thalamic and temporal cortex input to medial prefrontal cortex in rhesus monkeys. Exp Brain Res 1997; 115:430–444Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26 Selemon LD, Goldman-Rakic PS: Common cortical and subcortical targets of the dorsolateral prefrontal and posterior parietal cortices in the rhesus monkey: evidence for a distributed neural network subserving spatially guided behavior. J Neurosci 1988; 8:4049–4068Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Vogt BA, Rosene DL, Pandya DN: Thalamic and cortical afferents differentiate anterior from posterior cingulate cortex in the monkey. Science 1979; 204:205–207Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Baleydier C, Mauguiere F: The duality of the cingulate gyrus in monkey. Neuroanatomical study and functional hypothesis. Brain 1980; 103:525–554Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Hatanaka N, Tokuno H, Hamada I et al.: Thalamocortical and intracortical connections of monkey congulate motor areas. J Comp Neurol 2003; 462:121–138Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Cavada C, Company T, Tejedor J et al.: The anatomical connections of the macaque monkey orbitofrontal cortex. A review. Cereb Cortex 2000; 10:220–242Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31 Yeterian EH, Pandya DN: Corticothalamic connections of the superior temporal sulcus in rhesus monkeys. Exp Brain Res 1991; 83:268–284Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32 Gower EC: Efferent projections from limbic cortex of the temporal pole to the magnocellular medial dorsal nucleus in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol 1989; 280:343–358Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33 Markowitsch HJ, Emmans D, Irle E et al.: Cortical and subcortical afferent connections of the primate's temporal pole: a study of rhesus monkeys, squirrel monkeys, and marmosets. J Comp Neurol 1985; 242:425–458Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 Aggleton JP, Desimone R, Mishkin M: The origin, course, and termination of the hippocampothalamic projections in the macaque. J Comp Neurol 1986; 243:409–421Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35 Russchen FT, Amaral DG, Price JL: The afferent connections of the substantia innominata in the monkey, Macaca fascicularis. J Comp Neurol 1985; 242:1–27Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36 Hreib KK, Rosene DL, Moss MB: Basal forebrain efferent to the medial dorsal thalamic nucleus in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol 1988; 277:365–390Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37 Haber SN, Lynd-Balta E, Mitchell SJ: The organization of the descending ventral pallidal projections in the monkey. J Comp Neurol 1993; 329:111–128Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38 Parent A, Pare D, Smith Y et al.: Basal forebrain cholinergic and noncholinergic projections to the thalamus and brainstem in cats and monkeys. J Comp Neurol 1988; 277:281–301Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39 Middleton FA, Strick PL: Cerebellar projections to the prefrontal cortex of the primate. J Neurosci 2001; 21:700–712Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40 Kelly RM, Strick PL: Cerebellar loops with motor cortex and prefrontal cortex of a nonhuman primate. J Neurosci 2003; 23:8432Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41 Price JL: Subcortical projections from the amygdaloid complex. Adv Exp Med Biol 1986; 203:19–33Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42 Aggleton JP, Mishkin M: Projections of the amygdala to the thalamus in the cynomolgus monkey. J Comp Neurol 1984; 222:56–68Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43 Mega MS, Cummings JL: Frontal-subcortical circuits and neuropsychiatric disorders [see comments]. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1994; 6:358–370Link, Google Scholar

44 Mufson EJ, Pandya DN: Some observations on the course and composition of the cingulum bundle in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol 1984; 225:31–43Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45 Carmichael ST, Price JL: Limbic connections of the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex in macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol 1995; 363:615–641Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46 Amaral DG, Cowan WM: Subcortical afferents to the hippocampal formation in the monkey. J Comp Neurol 1980; 189:573–591Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47 DeVito JL: Subcortical projections to the hippocampal formation in squirrel monkey (Saimira sciureus). Brain Res Bull 1980; 5:285–289Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48 Shibata H, Yukie M: Differential thalamic connections of the posteroventral and dorsal posterior cingulate gyrus in the monkey. Eur J Neurosci 2003; 18:1615–1626Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49 Morris R, Petrides M, Pandya DN: Architecture and connections of retrosplenial area 30 in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). Eur J Neurosci 1999; 11:2506–2518Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50 Veazey RB, Amaral DG, Cowan WM: The morphology and connections of the posterior hypothalamus in the cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis). II. Efferent connections. J Comp Neurol 1982; 207:135–156Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51 Yeterian EH, Pandya DN: Corticothalamic connections of the posterior parietal cortex in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol 1985; 237:408–426Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52 Yeterian EH, Pandya DN: Corticothalamic connections of extrastriate visual areas in rhesus monkeys. J Comp Neurol 1997; 378:562–585Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53 Asanuma C, Anderson RA, Cowan WM: The thalamic relations of the caudal inferior parietal lobule and the lateral prefrontal cortex in monkeys: Divergent cortical projections from cell clusters in the medial pulvinar nucleus. J Comp Neurol 1985; 241:357–381Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54 Castaigne P, Lhermitte F, Buge A et al.: Paramedian thalamic and midbrain infarct: clinical and neuropathological study. Ann Neurol 1981; 10:127–148Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55 Graff-Radford NR, Damasio H, Yamada T et al.: Nonhaemorrhagic thalamic infarction. Clinical, neuropsychological and electrophysiological findings in four anatomical groups defined by computerized tomography. Brain 1985; 108:485–516Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56 Bogousslavsky J, Regli F, Uske A: Thalamic infarcts: clinical syndromes, etiology, and prognosis [published erratum appears in Neurology 1988 Aug; 38(8):1335]. Neurology 1988; 38:837–848Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57 Chung CS, Caplan LR, Han W et al.: Thalamic haemorrhage. Brain 1996; 119:1873–1886Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58 Trzepacz PT, Meagher DJ, Wise MG: Neuropsychiatric aspects of delirium, in The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. Edited by Yudofsky SC, Hales RE. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2002, 525–564Google Scholar

59 Bassetti C, Mathis J, Gugger M et al.: Hypersomnia following paramedian thalamic stroke: a report of 12 patients. Ann Neurol 1996; 39:471–480Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60 Lovblad KO, Bassetti C, Mathis J et al.: MRI of paramedian thalamic stroke with sleep disturbance. Neuroradiology 1997; 39:693–698Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61 Kopelman MD: The Korsakoff syndrome. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:154–173Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62 Belzunegui T, Insausti R, Ibanez J et al.: Effect of chronic alcoholism on neuronal nuclear size and neuronal population in the mammillary body and the anterior thalamic complex of man. Histol Histopathol 1995; 10:633–638Medline, Google Scholar

63 Zubaran C, Fernandes JG, Rodnight R: Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. Postgrad Med J 1997; 73:27–31Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64 Lugaresi E, Medori R, Montagna P et al.: Fatal familial insomnia and dysautonomia with selective degeneration of thalamic nuclei. N Engl J Med 1986; 315:997–1003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65 Perani D, Cortelli P, Lucignani G et al.: [18F] FDG PET in fatal familial insomnia: the functional effects of thalamic lesions. Neurology 1993; 43:2565–2569Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

66 Cortelli P, Perani D, Parchi P et al.: Cerebral metabolism in fatal familial insomnia: Relation to duration, neuropathology, and distribution of protease-resistent prion protein. Neurology 1997; 49:126–133Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67 Fiorino AS: Sleep, genes and death: fatal familial insomnia. Brain Res Rev 1996; 22:258–264Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

68 Benarroch EE, Stotz-Potter EH: Dysautonomia in fatal familial insomnia as an indicator of the potential role of the thalamus in autonomic control. Brain Pathol 1998; 8:527–530Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

69 Sandson TA, Daffner KR, Carvalho PA et al.: Frontal lobe dysfunction following infarction of the left-sided medial thalamus. Arch Neurol 1991; 48:1300–1303Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

70 Lim JS, Ryu YH, Kim BM et al.: Crossed cerebellar diachisis due to intracranial hematoma in basal ganglia for thalamus. J Nucl Med 1998; 39:2044–2047Medline, Google Scholar

71 Muller A, Baumgartner RW, Rohrenbach C et al.: Persistent Kluver-Bucy syndrome after bilateral thalamic infarction. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1999; 12:136–139Medline, Google Scholar

72 Clarke S, Assal G, Bogousslavsky J et al.: Pure amnesia after unilateral left polar thalamic infarct: topographic and sequential neuropsychological and metabolic (PET) correlations [see comments]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994; 57:27–34Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

73 Bogousslavsky J, Regli F, Delaloye B et al.: Loss of psychic self-activation with bithalamic infarction. Neurobehavioural, CT, MRI and SPECT correlates. Acta Neurol Scand 1991; 83:309–316Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

74 Pepin EP, Auray-Pepin L: Selective dorsolateral frontal lobe dysfunction associated with diencephalic amnesia. Neurology 1993; 43:733–741Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

75 Levasseur M, Baron JC, Sette G et al.: Brain energy metabolism in bilateral paramedian thalamic infarcts. A positron emission tomography study. Brain 1992; 115:795–807Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

76 Henselmans JM, de Jong BM, Pruim J et al.: Acute effects of thalamotomy and pallidotomy on regional cerebral metabolism, evalutated by PET. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2000; 102:84–90Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

77 Tamura A, Tahira Y, Nagashima H et al.: Thalamic atrophy following cerebral infarction in the territory of the middle cerebral artery. Stroke 1991; 22:615–618Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

78 Ogawa T, Yoshida Y, Okudera T et al.: Secondary thalamic degeneration after cerebral infarction in the middle cerebral artery distribution: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology 1997; 204:255–262Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

79 Sakashita Y, Matsuda H, Kakuda K et al.: Hypoperfusion and vasoreactivity in the thalamus and cerebellum after stroke. Stroke 1993; 24:84–87Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

80 De Reuck J, Decoo D, Lemahieu I et al.: Ipsilateral thalamic diaschisis after middle cerebral artery infarction. J Neurol Sci 1995; 134:130–135Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar