Frequency of Delirium in a Neurological Emergency Room

Abstract

The authors present a cross-sectional survey designed to evaluate the presence of delirium in patients with neurological emergencies. Two hundred and two patients were included in the study: 14.9% of subjects had delirium; 62.4% had no arousal disturbances; and 22.7% presented a coma or stupor state. Findings revealed that the presence of a cerebral infection, the presence of multiple etiologies, and the location of lesions in the frontal and temporal lobes were all associated with delirium. Results substantiate that delirium is a frequent occurrence in neurological patients and that the presence of multiple etiologies must be investigated in each patient.

Delirium is a neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by a fluctuating mental and behavioral condition with reduction in alertness, global cognitive decline, and, frequently, by the presence of delusional-hallucinatory phenomena, disturbances in the circadian rhythm as expressed by insomnia and daytime sleepiness, mood swings and gross disturbances of behavior, mainly in the hyperactive form of the syndrome.1

Delirium has been estimated to be present in 0.4% of the general population between 18 and 55 years; the frecuency increases up to 1.1% in older patients. In a general hospital setting, it occurs in 10–30% of the hospitalized patients;2,3 and is associated with a significant mortality rate.2,4,6,7 Regarding neurological patients, most information comes from case series or retrospective studies, which describe etiological conditions and risk factors such as stroke,8 epilepsy, preexistent dementia, drugs and systemic conditions (e.g., infections, dehydration), as described in a European study of 64 patients admitted because of an acute confusional state into a neurological ward.9 The study of delirium in neurological patients is an opportunity to obtain relevant clinical information related to the neurofunctional basis of this syndrome. Since there is no animal model of delirium, its underlying physiopathology has been formulated at a theoretical level, considering extrapolations from other syndromes, like psychosis and dementia; the anatomical lesions described in case reports and series and the few electrophysiological studies are the only available data. Hence, systematic studies of delirium in neurological patients are needed to improve the neurobiological understanding of this syndrome.

The aim of this study was to determine the frequency of delirium in subjects with neurological emergencies, and also, the neurological etiologies and associated factors related with the presence of delirium.

METHOD

We developed a cross-sectional survey in order to include all adult patients admitted to the emergency ward of the National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery, in Mexico City, (a neurological referral center), from April 1, 2001 to July 31, 2001. A consent form was obtained for all cases, signed by two family members responsible for the patient, or by the patient himself when his mental status permitted a proper consent, as required by the institutional Ethics Committee. All subjects were evaluated by a clinical neuropsychiatrist, who performed a mental status examination on each patient, as well as an interview with the relatives and caregivers. Delirium Rating Scale (DRS), Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE) and Coma Glasgow Scale ratings were also registered. The final diagnosis of delirium was made according to DSM–IV criteria, and confirmed by a rating of 11 or above on the DRS.10 This scale is well known for its capacity to distinguish between delirium and other neuropsychiatric syndromes, like psychosis and dementia, with high diagnostic validity with a cutoff point of 11 in Spanish-language patients.11 Also, this cutoff point is useful to establish the distinction between delirium and stupor or coma states.11 This distinction was also achieved by means of Glasgow Coma Scale12 and operative clinical definitions derived from Richard L. Strub and F. William Black concepts13: “Stupor and semicoma are used to describe patients who respond only to persistent and vigorous stimulation. The stuporous patient does not rouse spontaneously and, when aroused by the examiner, can only groan or mumble and move restlessly in the bed. In such a patient, there is extensive brain dysfunction; because of the markedly reduced level of consciousness, no meaningful assessment of the content of mental functioning is possible. Coma is traditionally applied to those patients who are completely unarousable.” Regarding MMSE, we used a cutoff point of 24 or less to establish a cognitive disturbance, which was one of DSM–IV criteria we used to diagnose delirium.

Patients were evaluated daily since the admission day to their last day in the emergency room; if the patient changed her or his level of alertness from a previous state (normal alertness, stupor or coma) into a delirium state, he or she was classified as having delirium and eliminated from the previous category. Rating scales were corrected for that patient at that moment. This was necessary considering the fluctuating nature of confusional states.

Delirium was classified according to the subtypes proposed by Lipowski,14 as hypoactive (as defined by a marked reduction in alertness and psychomotor behavior), hyperactive (as defined by an increase in psychomotor behavior and hypervigilance) and mixed.

A cognitive impairment as measured by the MMSE,15 a test that is also well described in Spanish-language psychiatric literature,16 was also a requisite for the diagnosis. Results of standard laboratory studies were registered in all cases. A clinical neurologist from the emergencies ward, blind to the psychiatric diagnosis, established an etiological diagnosis, and a radiologist, blind to the rest of the study, evaluated computed tomography (CT) scans obtained in every patient in order to locate the lesions. A data analysis was performed, initially with descriptive statistics and normality tests, and later we conducted a bivariate analysis with Pearson chi-square tests, Fisher tests, and Mann-Whitney tests,17 to compare the clinical, laboratory and imaging data of the patients with delirium and those without delirium. Finally, a logistic regression analysis was performed with all variables that were found to be significantly different on the bivariate analysis, in order to control the potential influence of confounding factors. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS-10 for Windows program.17

RESULTS

Two hundred and two adult patients were evaluated, with a mean age of 49.5 years (SD = 19.3); 60.9% were women, and 39.1% were men. Delirium was present in 14.9% (N=30); a coma or stupor state was present in 22.7% (N=46), and 62.4% (N=126) of subjects had no arousal disturbances. Within the delirium group, the most frequent subtype of delirium was the hyperactive form (46.7%, N=14); the hypoactive form was present in 33.3% (N=10), and 20% (N=6) of patients had a mixed subtype. DRS was completed in all delirium patients, but MMSE could not be completed in 16 (33.3%) of the delirium patients, neither in patients with coma and stupor states. This fact highlights the advantages of a clinimetric tool like DRS, which is not based exclusively in direct data from a formal mental status examination, but also in general observations and indirect data as provided by relatives and nurses, so it can be used even in uncooperative patients.

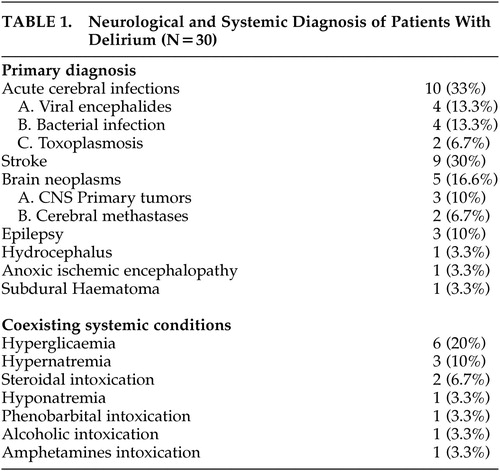

Table 1 shows the main neurological diagnoses that were established in the group of patients with delirium; the most frequent were cerebral infections, followed by cerebrovascular diseases and cerebral neoplasms. Also, Table 1 shows the presence of different systemic conditions that coexisted with neurological diseases.

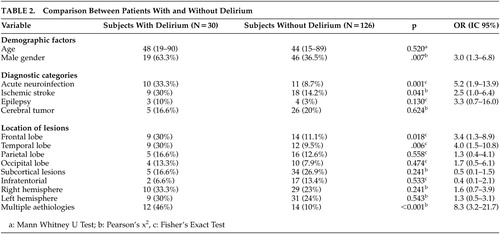

We performed a comparative analysis between patients with delirium and those who had no arousal disturbances. Patients with coma or stupor were excluded from this statistical analysis, because the comparison between three groups would (by means of ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis tests) need a larger sample size and other conditions not met in this sample. Table 2 shows the results of comparative analysis, and shows that delirium patients are more frequently male, and present a higher proportion of cerebral infections, cerebrovascular diseases, frontal and temporal lobe lesions, and multiple simultaneous etiologies (This variable was classified as present when patients had a single neurological condition, and simultaneously one or more of the abnormal systemic conditions listed at the end of Table 1).

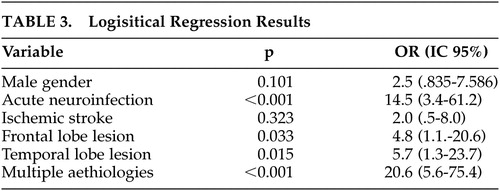

Table 3 shows the results of the logistic regression method; once this statistical procedure was done, the variables significantly associated with the presence of delirium were: cerebral infections, frontal and temporal lobe lesions, and multiple etiologies.

DISCUSSION

According to our search of the medical literature, this is the first study, to our knowledge, to determine the frequency of delirium in neurological patients, and to evaluate systematically the influence of various demographic, clinical and neurobiological variables. A retrospective study regarding the frequency of delirium in neurological patients has been published previously,18 but it is well known that retrospective medical record reviews are very imprecise in establishing the diagnosis of delirium.19 The frequency of delirium we found (14.9%) is within the range observed in general hospitals and in other specialties,2,3 and suggests that, even when delirium is essentially a brain disorder, the influence of systemic factors is very important in the production of the syndrome.

Regarding the subtype of delirium, our results show a majority of cases with the hyperactive form; this has also been observed in other medical populations. For instance, in a retrospective study of 90 hospitalized patients from an oncology setting, diagnosed as having delirium, the hyperactive subtype was the commonest form observed (71%) and had the shortest duration and best outcome.20 Nevertheless, since the hyperactive form shares clinical characteristics with psychotic syndromes, it may be misdiagnosed as psychosis. Previous works suggest that the subtype of delirium could be related with specific location of lesions. For instance, orbitofrontal, cingulated and hippocampal lesions, mainly on the right hemisphere, would be associated with agitated delirium, and hypoactive delirium would be related to left hemisphere lesions.21,22 In our sample, these observations were not confirmed, perhaps as a result of the relatively small sample size.

One of the interesting findings of our work is the high frequency of brain infections in the delirium group. Definitively, this is influenced by the socioeconomical context of the study, as Mexico City is the capital of a developing country. Brain infections are well described also in developed countries as causes of delirium, although not with the same frequency.23 In our study, cerebral infections were the only diagnostic category significantly associated with delirium, with an odds ratio (OR) of 14.5. From a practical point of view, the clinician from a developing country should consider a brain infection as a main diagnostic hypothesis while attending a neurological patient with delirium.

Regarding other causes of delirium, cerebrovascular diseases were more frequent in the delirium group as compared to the nondelirium group. Notwithstanding, after the multivariate analysis no significant association was found. This suggests that other factors associated both to delirium and cerebrovascular diseases could be acting as confounding variables (including the presence of coexisting systemic conditions and the size and location of lesions). Cerebral neoplasms were also frequent causes of delirium in our sample, but no association was established by statistical procedures. In our sample, there is a noticeable lack of representation of traumatic problems, according to the characteristic of our neurological center. This is related to one of our main limitations of our study, to be confined to a particular context. Another relevant limitation is the relatively small sample size, which could provoke type II errors, for instance, our observation of a lack of association between delirium and cerebrovascular disease.

Notwithstanding, the comparison within our sample between delirium and nondelirium patients suggest that some observations done here could be replicated in another clinical setting: that is the case of multicausality as a composed factor related to delirium. Our finding of a strong association between multiple etiologies and delirium, has been suggested previously; for instance, a prospective study of delirium in elderly patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital showed that coexistent structural brain disease predisposing to delirium was found in 81% of the patients in their sample.24 The role of underlying brain disease in delirium has been well described in classical texts.25 In our study, the coexistence of two or more neurological problems, or more often, the combination of a neurological and a systemic factor was found to be a significant risk factor for delirium; from a clinical point of view, this suggests that a clinician finding one cause for delirium in a particular patient should frequently consider the possibility of a second or even third cause for this patient, as delirium is commonly present in multisystemically ill patients.

Finally, from the theoretical point of view, our results show a link between frontal and temporal lesions and the presence of delirium. It is probable that temporal lobe dysfunction, in particular hippocampal dysfunction, could be related to the cognitive features of delirium, like temporal disorientation, a characteristic that has been previously remarked.26 Frontal lobes are also part of a wide-spread cortico-subcortical system responsible for working memory, sustained attention, executive functions, which are neuropsychological domains severely altered in delirium. Previous studies report this anatomical network as part of the system disrupted in confusional states.7,26–27 An important role of right hemisphere28 and subcortical structures (such as the thalamus and mesencephalon) have been proposed in the pathogenesis of delirium,29,30 but our data did not provide evidence to support that hypothesis. It is necessary to develop further studies with larger sample sizes and different imaging procedures in order to confirm the clinical-pathological models previously formulated.

|

|

|

1 Van der Mast RC: Delirium: The underlying pathophysiological mechanisms and the need for clinical research. J Psychosom Res 1996; 41:109–113Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Fann JR: The epidemiology of delirium: A review of studies and methodological issues. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry 2000; 5:64–74Medline, Google Scholar

3 Folstein MF, Bassett SS, Romanoski AJ, et al. The epidemiology of delirium in the community. The Eastern Baltimore Ment Health Survey Int Psychogeriat 1991; 3:169–176Google Scholar

4 Trzepacz PT, Teague G, Lipowski Z: Delirium and other organic mental disorders in a general hospital. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1985; 7:101–106Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Rössler W, Hewer W, Fätkenheuer B, et al: Excess mortality among elderly psychiatric in-patients with organic mental disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 1677:527–532Crossref, Google Scholar

6 Weddington WW: The mortality of delirium: an underappreciated problem? Psychosomatics 1982; 23:1232–1235Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Inouye S: The dilema of delirium: clinical an research controversies regarding diagnosis an evaluation of delirium in hospitalized elderly medical patients. Am J Med 1994; 97:278–288Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Ferro JM: Hyperacute cognitive stroke syndromes. J Neurol 2001; 248:841–849Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Bassetti C, Regli F: Schweizerische Rundschau fur Medizin Praxis 83(8):226–231,1994Google Scholar

10 Trzepacz PT, Baker RW, Greenhouse J: A symptom rating scale for delirium. Psychiatriy Res 1988; 23:89–97Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Secin R, Esponda J, Rivera B: Validación del delirium rating scale (DRS) en español en una unidad de cuidados intensivos. Psiquis 1998; 7:7–14Google Scholar

12 Teasdale G, Jennett B: Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. Lancet 1974; 2:81Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Strub RL, Black FW: The Mental Status Examination in Neurology. Fourth ed. FA Davis Company, Philadelphia, 2000Google Scholar

14 Lipowski ZJ: Delirium: Acute Confusional State. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

15 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Becerra B, Ortega-Soto H, Torner C: Validez y reproductibilidad del examen cognoscitivo breve (Mini-mental state examination) en una unidad de cuidados especiales de un hospital psiquiátrico. Salud Ment 1992; 15:41–45Google Scholar

17 Norman GR, Streiner DL: Bioestadística. Harcourt, Madrid, 1994. pp 128et al: A Referral pattern of neurological patients to psychiatric Consultation-Liaison Services in 33 European hospitals. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001 May-Jun;23(3):152-157Google Scholar

19 Johnson JC, Kerse NM, Gottlieb G, et al: Prospective versus retrospective methods of identifying patients with delirium J the Am Geriatrics Society 1992; 40:316–319Google Scholar

20 Olofsson SM, Weitzner MA, Valentine AD, et al: A retrospective study of the psychiatric management and outcome of delirium in the cancer patient Supportive Care in Cancer 1996; 4:351–357Google Scholar

21 Trzepacz PT: Is there a final common neural pathway in delirium? Focus on acetylcholine and dopamine. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry 2000; 5:132–148Medline, Google Scholar

22 Inao S, Kawai T, Kabeya R, et al: Relation between brain displacement and local cerebral blood flow in patients with chronic subdural haematoma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001; 71:741–746Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Warshaw G, Tanzer F: The effectiveness of lumbar puncture in the evaluation of delirium and fever in the hospitalized elderly. Archives of Family Med 1993; 2:293–297Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Koponen HJ, Riekkinen PJ: A prospective study of delirium in elderly patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Psychol Med 1993; 23:103–109Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Plum F, Posner J. The diagnosis of stupor and coma. 3rd Ed. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1982Google Scholar

26 Mesulam M: Behavioral neurology. CNS series. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1983Google Scholar

27 Lipowski ZJ: Transient cognitive disorders (delirium, acute confusional states) in the elderly. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:1426–1436Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Trzepacz PT: Update on the neuropathogenesis of delirium. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disorder 1999; 10:330–334Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Spiegel EA, Wycis HT, Orchink C, et al: Thalamic chronotaraxis. Am J Psychiatry 1956; 113:97–105Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30 Schiff N, Plum F: The role of arousal and “Gating” systems in the neurology of impaired consciousness. The journal of clinical neurophysiology 2000; 17:438–452Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar