Long-Term Treatment of Hashimoto’s Encephalopathy

Abstract

Hashimoto’s encephalopathy (HE) has been described as an encephalopathy, with acute or subacute onset, accompanied by seizures, tremor, myoclonus, ataxia, psychosis, and stroke-like episodes, with a relapsing/remitting or progressive course. HE patients have positive antithyroid antibodies, are usually in a subclinical hypothyroid state, have elevated cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) protein, and have nonspecific electroencephalogram (EEG) and imaging abnormalities in the absence of CNS infection, tumor, or stroke. The authors present two cases of HE, demonstrating an excellent response to high dose steroids acutely followed by long-term treatment with steroids and other immunomodulatory agents. A review of the literature is also provided.

Hashimoto’s encephalopathy (HE) was first described in 1966 by Brain et al.,1 who reported a case of a 48-year-old man with hypothyroidism, multiple episodes of encephalopathy, stroke-like symptoms, and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis confirmed by elevated antithyroid antibodies. A recent review of the literature2 reported that 105 cases have been described since the Brain et al. study. However, only 85 of those cases met their criteria for diagnosis, which were as follows: presence of encephalopathy and elevated antithyroid antibodies in the absence of a central nervous system (CNS) infection, tumor, or stroke. A recent review3 reported that there were less than 50 well-diagnosed cases in the literature. HE has also been referred to as an encephalopathy associated with autoimmune (or Hashimoto’s) thyroiditis or as a steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with thyroid autoimmunity due to the typical response to treatment with steroids.4,5

In this study, we report two cases that were treated and followed up in our facility. We then provide a review of the literature and discuss the long-term treatment of the patients presented in the two cases. The MEDLINE database from 1966 to August 2004 was searched using the terms “Hashimoto’s encephalopathy,” “Hashimoto” or “autoimmune thyroiditis” and “encephalopathy.” One hundred one citations resulted. Citations were reviewed if they referred to encephalopathy associated with elevated serum antithyroid antibodies in the absence of CNS infection, tumor, or stroke. References cited within articles were reviewed as well. Foreign language citations were reviewed when translation was available.

CASE 1

A 54-year-old right-handed man, who works as a furniture salesman, developed confusion on a business trip. He recovered in 3 days without treatment. Electrolytes, thyroid function tests (TFTs), liver functions tests (LFTs), and toxicology screen, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) brain imaging, carotid dopplers, electroencephalogram (EEG), echocardiogram, and chest X-Ray were all normal. The patient’s past medical history included hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypothyroidism (treated with levothyroxine) following partial thyroidectomy for a benign nodule, melanoma resection from the posterior thorax without known recurrence, and a remote history of smoking cigarettes.

One week later, the patient was hospitalized for confusion, drowsiness, nonfluent speech with word-finding difficulties, and involuntary jerks of the arms. He recovered spontaneously over 9 days. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 31 mm/hr, and antinuclear antibody (ANA), double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), toxicology and HIV tests were negative. Cisternal tap disclosed four red blood cells (RBC)/mm3, 2 white blood cells (WBCs)/mm3, glucose 61 mg/dl and protein 284 mg/dl. CSF culture was negative. Oligoclonal bands, cytology, and studies for cryptococcus, toxoplasmosis, herpes simplex virus (HSV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), lyme, and syphilis were also normal. EEG, brain MR imaging and angiogram, conventional cerebral angiogram, and spinal MRI were negative. Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) disclosed a patent foramen ovale without septal aneurysm; lower extremity doppler study was negative for venous thrombosis. Hypercoaguable panel and occult malignancy work-ups were negative.

After discharge, repeat cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) examination and positron emission tomography (PET) of the brain were normal. When symptoms recurred 1 month later, CSF protein was 99 mg/dl with normal cell counts and glucose. Imaging and EEG remained normal. Urinary screen for heavy metals and amino acids and screening for urinary porphyrins were negative. Antithyroid peroxidase antibodies (anti-TPO) were elevated at 22.7 (positive; normal 0–2).

He again improved without treatment, only to relapse within 2 months with confusion, involuntary jerking movements of the extremities, lethargy, and rigidity. Severe retropulsion was noted on attempts to stand. Routine laboratory studies, comprehensive toxicology screen, LFTs, ammonia, vitamin B12, folate, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), rapid plasma reagin (RPR), lactate, pyruvate, ESR, C-reactive protein (CRP), ANA, rheumatoid factors (RF), autoantibodies to Ro/SS-A and La/SS-B (SSA and SSB), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), complements, and paraneoplastic antibodies were negative. mtDNA was negative for mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like syndrome (MELAS), myoclonic epilepsy with ragged red fibers (MERRF), MELAS/MERRF overlap, and Leigh syndrome. Imaging was negative and prolonged video/EEG monitoring showed diffuse slowing but did not disclose any epileptiform activity.

A diagnosis of HE was suspected due to the extensive negative work-up, the recurrent encephalopathy, motor symptoms, and positive antithyroid antibodies. He was treated with intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone 1 g daily for 3 days, which resulted in dramatic improvement. He was then discharged home on tapering doses of oral prednisone.

Three mild episodes ensued at roughly monthly intervals; these were treated promptly with IV methylprednisolone which likely limited symptom development. Laboratory evaluation during those episodes included normal TFTs, anti-TPO<60 IU/ml (negative; normal<60) and antithyroglobulin antibodies (anti-Tg) 166 IU/ml (positive; normal<60). At that point, 8 months after symptom onset, oral methotrexate was begun at 2.5 mg weekly and titrated up gradually (eventually to a dose of 15 mg weekly), but breakthrough symptoms early on necessitated the addition of prednisone 60 mg daily, which was later tapered slowly. Since then, he has been symptom-free for 19 months, with most recent doses of methotrexate 5 mg weekly and prednisone 14 mg every other day. During this period of time, he has been able to work, do all his instrumental activities of daily living and hobbies. He reports only minimal residual forgetfulness and occasional irritability.

CASE 2

A 79-year-old right-handed woman developed disorientation, delusions, incontinence, and jerky involuntary movement of the neck and upper thoracic regions. A seizure with postictal left hemiparesis ensued and was treated with phenytoin and valproic acid. Brain MRI was normal for age; multiple EEGs showed diffuse or multifocal slowing. Conventional cerebral angiography demonstrated bilateral extracranial carotid artery stenosis but no evidence of vasculitis. Past medical history included rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism (treated with levothyroxine), hypertension, osteoporosis, asthma, coronary artery disease, major depression, hyperlipidemia, and folic acid deficiency.

She remained encephalopathic for the next few weeks, was then discharged from the hospital briefly but returned in status epilepticus, which evolved during attempted reduction of anticonvulsants. Laboratory evaluation included TSH 6.76 μIU/ml, ESR 30 mm/hour, CRP 1.36, normal complement levels, and negative anticardiolipin antibodies. CSF revealed 1 WBC/mm3, protein 76 mg/dl, negative 14–3–3 protein, VDRL of the United States Public Health Service (VDRL), and oligoclonal bands. Antimicrosomal antibodies (anti-M) were elevated at 1:1600.

A diagnosis of HE was suspected because of the extensive negative work-up, encephalopathy, unexplained new onset seizures, motor symptoms, prior autoimmune disorder, and positive antithyroid antibodies. Treatment with high dose IV methylprednisolone was begun. Dramatic improvement occurred but without full return to premorbid status.

She required oral prednisone maintenance as an outpatient and when the dose was decreased below 30 mg daily several months later, encephalopathy recurred. This consisted of somnolence, confusion, disorientation, fluent but occasional nonsensical speech, short-term memory impairment, moderate to severe hearing impairment, and mild to moderate lower extremity weakness. Laboratory evaluation included anti-Tg 14 IU/ml (negative; normal<60) and anti-TPO 94 IU/ml (positive; normal<60), CRP 3.3, normal vitamin B12, CBC except elevated mean corpuscular volume (MCV), TSH, serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP), electrolytes, LFTs (except albumin 2.9g/dl), ammonia, ESR, RF, ANA, complements, dsDNA, SSA, SSB, and ANCA. Initial CSF showed 0 WBC/mm3, 6 RBC/mm3, glucose 57 mg/dl, and protein 45 mg/dl. Repeat CSF showed 9 WBC/mm3 (with 73 neutrophils, 6 lymphocytes, and 21 monocytes), 1604 RBC/mm3, glucose 57 mg/dl, protein 110 mg/dl, negative oligoclonal bands, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), and cultures. Urine and blood cultures were negative. EEG showed mild to moderate generalized slowing, but no focal abnormality or epileptiform activity. Brain MRI showed generalized cerebral atrophy and chronic small vessel ischemic disease, without evidence of stroke, intracranial stenosis, or vasculitis. CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was unremarkable.

After 3 days of high dose IV methylprednisolone, she improved significantly but did not return to baseline. A combination of monthly cyclophosphamide infusions and a slow prednisone taper followed. Two months later she returned to her cognitive baseline with mild short-term memory and naming difficulties. Her lower extremity strength improved and she was able to walk a little with a walker.

She was symptom-free for another 4 months after receiving a total of 6 doses of cyclophosphamide, when she developed another episode of encephalopathy. She responded partially to two courses of high dose IV methylprednisolone, with fluctuation of her symptoms in the context of a urinary tract infection and later an upper respiratory infection. Consequently, it was decided to change the cyclophosphamide to oral cellcept 250 mg twice daily and continue prednisone 30 mg daily. The following 4 months, her symptoms continued to wax and wane, but after tapering off phenytoin and reducing the dose of valproic acid, while increasing the dose of cellcept, she started to improve. Since then, she has been symptom-free for 2 months, returned to her cognitive baseline and started walking, with most recent doses of cellcept 1000 mg twice daily and prednisone 20 mg daily.

DISCUSSION

Both of our cases met the above mentioned criteria for HE; they had treated hypothyroidism, abnormal EEGs while symptomatic, and demonstrated an excellent response to high dose steroids in the acute phase. However, their clinical course and long-term treatment were different. The younger patient had a relapsing/remitting course, which responded well to long-term immunomodulatory treatment resulting in extended remission. The older patient had a more progressive course, which did not respond as well to various long-term treatments. Other defining features in our cases included an elevated CSF protein during exacerbations with normalization during periods of remission in the first case, and hearing impairment and seizures escalating to status epilepticus at one point, both of which improved with long-term treatment in the second case.

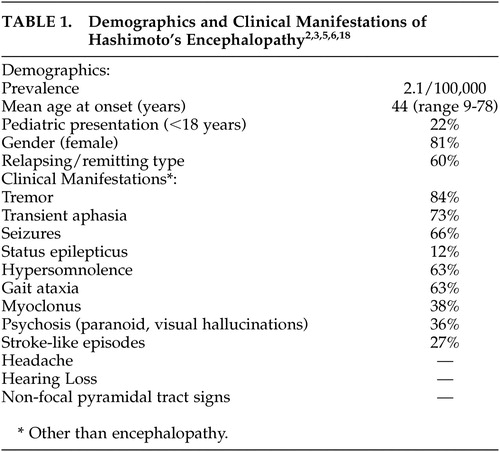

HE is a rare disease with a recent estimated prevalence of 2.1/100,000.6 A review of the literature2 reported a mean age at onset of 44 years, about a fifth of cases under 18 years of age, and 4:1 female/male ratio (see Table 1). Clinical findings did not differ among age groups. Moreover, clinical findings are variable and nonspecific. Two types of HE have been suggested: relapsing/remitting, also referred to by some as vasculitic type, which manifests with encephalopathy and stroke-like episodes. Diffuse progressive type, which has an insidious onset and progressive course with occasional fluctuations and manifests with psychiatric symptoms and dementia. Either type may also present with tremor, myoclonus, seizures, stupor, or coma.7 Encephalopathy usually develops over 1 to 7 days, and the majority of cases present with a relapsing/remitting course, tremor, transient aphasia, seizures (nearly a fifth in status epilepticus as seen in our second case), hypersomnolence, and gait ataxia. Also commonly seen are myoclonus, psychosis, and stroke-like episodes (see Table 1, 2, 3). Clinical findings in the pediatric population are variable as in adults and usually consist of confusion, seizures, and hallucinations, or manifest with a progressive course of cognitive decline.8 On the other hand, cases of HE in the elderly are associated with cognitive impairment at onset.9

Laboratory evaluation shows that the majority of cases of HE have elevated CSF protein and almost no nucleated cells/mm3, while oligoclonal bands are seen frequently (see Table 2). One case series also noted that the elevation in CSF protein was seen during acute exacerbations mostly, as illustrated by our first case.10 The EEG is abnormal in nearly all cases, most commonly showing diffuse or generalized slowing or frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity (FIRDA); prominent triphasic waves, focal slowing, epileptiform abnormalities, photoparoxysmal and photomyogenic responses are also commonly seen. Follow-up EEG after treatment with steroids showed resolution of abnormalities in all 17 cases in one series and in the majority of cases in another. One-half of cases of HE have abnormal imaging findings (on CT or MRI) including nonspecific focal subcortical white matter abnormalities, cerebral atrophy, and diffuse subcortical or focal cortical abnormalities; in one report follow-up MRI after treatment with steroids showed resolution of abnormalities in 5/11 cases (45%). Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) studies show focal hypoperfusion in the majority of cases, global hypoperfusion in some, and normal findings in the rest (see Table 3).2,5,7,11–13 As indicated above, EEG and imaging studies in HE are abnormal but nonspecific and do not necessarily help in making the diagnosis but help exclude other diagnoses.

There are very few reported pathological evaluations of HE cases. One autopsy showed lymphocytic vasculitis of venules and veins in the brainstem,14 while another autopsy showed diffuse but mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltration, as well as diffuse gliosis involving gray matter more than white matter.15 Two biopsies showed lymphocytic perivascular cuffing and lymphocytic vasculitis of venules and arterioles.2,16

Thyroid dysfunction in HE is variable despite similar neurological findings and is unlikely by itself to account for the encephalopathy.2 In a recent review of the literature, 35% of cases had subclinical hypothyroidism; 22% were euthyroid not on levothyroxine; 20% had overt hypothyroidism; and 8% were euthyroid on levothyroxine (as were our two cases); 7% had hyperthyroidism (5% overt, 2% subclinical); 6% had unknown thyroid status; and 1% did not have thyroid disease. A goiter was present in 62% of cases (see Table 2). Of the above cases with subclinical or overt hypothyroidism, 17% improved following treatment with levothyroxine alone, while 40% improved following combined treatment with levothyroxine and steroids.2 It is somewhat surprising that some cases improved with levothyroxine treatment alone. However, it may be that those cases were destined to improve spontaneously.

Antithyroid antibodies regularly checked in the serum in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis include antithyroid peroxidase antibodies, anti-TPO (previously known as antithyroid microsomal antibodies, anti-M), and antithyroglobulin antibodies, anti-Tg. The prevalence of those antibodies in the general population has been reported at 11% (5–20% in normal older adults, especially in females, and 2–10% in young adults).2,7,17 In the above review multiple antibodies were checked in 71% of cases with HE and 24% reported a normal value for one of the antibodies. Anti-M and anti-TPO were present in 95–100% of cases and anti-Tg in 73% (see Table 2). There was no significant relationship between the type of antibody present and the neurological findings.2 Some studies suggested that antithyroid antibody level elevation is proportional to the degree of disease activity since levels have been shown to decrease after treatment with steroids.18 However, other studies showed that antibody levels increased again after withdrawal of steroids and therefore argued against this relationship.7 Moreover, there is no evidence that the antibodies play a specific role in the pathogenesis of HE, but rather possibly represent a marker for another autoimmune process involving the brain.2 Recent studies also demonstrated the presence of antithyroid antibodies in the CSF of subjects with HE. Intrathecal synthesis of the antibodies was suggested, and a lack of association between antibody titers and disease severity and stage of treatment was reported.6,19

The etiology of HE is posited to be autoimmune due to its association with other autoimmune disorders (myasthenia gravis, glomerulonephritis, primary biliary cirrhosis, splenic atrophy, pernicious anemia, and rheumatoid arthritis), female predominance, inflammatory findings in CSF, and typical response to treatment with steroids.7,17,18 One proposed mechanism of pathogenesis suggested that HE is an autoimmune cerebral vasculitis, perhaps related to immune complex deposition. This hypothesis is supported by the focal and/or global neurological symptoms and findings on EEG, MRI and SPECT seen in HE.7,18,20–22 However, as described above the limited pathological data in HE is suggestive though not completely confirmatory of this mechanism, and cerebral angiography has been normal in multiple cases, including our two cases.11,17Alternatively, a recent review suggested that HE is a recurrent form of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) with a presumed T-cell mediated lymphocytic vasculopathy accompanied by blood-brain barrier breakdown.10 Vasculopathy rather than vasculitis may be a more appropriate term to describe the mechanism at work in HE. This is supported by the readily reversible rather than destructive nature of the disease which may represent cerebral edema, the lack of supportive pathological demonstration of vessel destruction, the low mortality rate, and the frequent near complete recovery of patients clinically and on imaging studies, as will be discussed below.

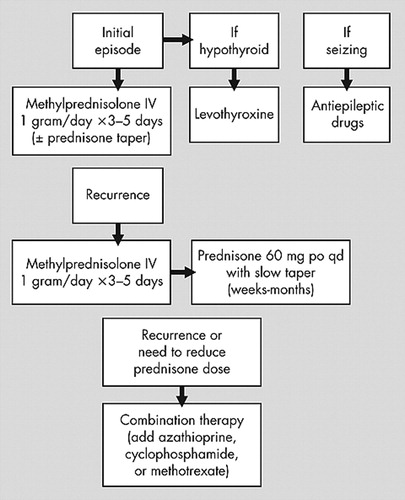

Treatment of HE has consisted of immunomodulatory agents (mostly steroids) and/or thyroid-acting agents (mostly levothyroxine), as well as antiepileptic drugs for seizures and status epilepticus.17 Treatment of initial or acute/subacute presentation of HE usually consists of high dose oral prednisone (50–150 mg/day) or high dose IV methylprednisolone (1 g/day) for 3–7 days, which typically results in marked improvement of neurological symptoms (including reduction of refractory seizures) within 1 week (some report 4–6 weeks) and sometimes as early as 1 day, as seen in our two cases. Recurrences/relapses usually respond similarly.4,7,11,23 To avoid recurrences a slow taper of prednisone over weeks to months, depending on the clinical response, has been suggested.11,18

Cases with multiple recurrences or cases failing to respond to the above therapy have been placed on long-term treatment with prednisone, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, plaquenil, methotrexate, periodic intravenous immune globulin (IVIG), plasma exchange, and various combinations of these treatments, usually with good success.4,7,24 We now add cellcept to the list. Our review of the literature indicates that 4 of 5 cases were treated successfully with azathioprine and prednisone, while 1 case failed treatment with azathioprine alone.4,10,20,23 Two of 3 cases were treated successfully with cyclophosphamide alone, while 1 of 2 cases was treated successfully with cyclophosphamide and prednisone.4,17 Two cases were treated successfully with methotrexate, 1 with (our case) and 1 without prednisone.4 One of 2 cases was treated successfully with periodic IVIG alone.4,12 One case was treated successfully with plasma exchange and prednisone, while 1 case failed treatment with plasma exchange alone.4,24 One case was treated successfully with plaquenil and prednisone.4 One case (our case) was possibly treated successfully with cellcept and prednisone (a longer follow-up period is needed to determine treatment success). As indicated above there is almost no information about long-term treatment of HE with monotherapy other than prednisone. The little information available about combination therapy suggests reasonable success, most notably when azathioprine is added to prednisone. Therefore, if prednisone monotherapy fails or one wants to reduce the dose of prednisone to avoid side effects, combination therapy is recommended. However, long-term immunomodulatory treatment is not risk free—it may result in serious side effects and requires frequent monitoring of clinical and laboratory parameters. See Figure 1 for a suggested algorithm for the treatment of HE.

Normalization of CSF, EEG, and quantitative neuropsychological testing serves as a good indicator of treatment efficacy, though EEG normalization often lags about 2 weeks after clinical recovery.7,12,13 A review of the literature reported improvement in 98% of cases treated with steroids, 92% treated with steroids and levothyroxine, and 67% treated with levothyroxine, while 9% of cases did not improve with any of the above combinations.2 90% of cases stayed in remission even after discontinuation of treatment.7,11 Duration of disease has been reported to range between 2 and 25 years.25 Cases of the relapsing/remitting type usually did better than the progressive type, a few of which developed irreversible persistent cognitive impairment.7 One study noted that incomplete recovery might be more frequent in the elderly.9 However, HE has an overall favorable long-term prognosis with treatment.7,20 Three of 85 cases died, 2 while still being treated.2

The clinical findings of HE resemble those seen in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), which is a fatal and incurable disease. One series reported an initial diagnosis of prion disease in 53% of cases later diagnosed as HE (8 CJD and 2 fatal familial insomnia cases).5 Since HE has a favorable prognosis with treatment it is important to include it in the differential diagnosis of CJD. Moreover, despite the report of several cases of HE being negative for 14–3–3 protein in the CSF (a useful marker for CJD), there has been a report of one positive finding with HE. Conversely, elevated antithyroid antibodies have been reported in CJD, underscoring the difficulty in differentiating the two conditions clinically.26–29

CONCLUSION

Both the etiology and pathophysiology of HE must be further elucidated, with the goal of facilitating diagnosis of the disorder, perhaps by developing more specific diagnostic markers. The recently quoted prevalence figures for HE are higher than expected when compared to the few cases reported in the literature, which suggests that this condition is presently underdiagnosed. Therefore, it remains important to maintain a high clinical suspicion for HE since it is a readily treatable condition that carries a good prognosis, unlike many of the other diagnoses it resembles.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Bradley F. Boeve, who advised in the initial treatment of Case 1, and Jeffrey L. Cummings, M.D. for reviewing the manuscript.

The authors also thank Cases 1 and 2 and their families who gave permission to report the cases.

FIGURE 1. Algorithm for the Treatment of Hashimoto’s Encephalopathy

|

|

|

1 Brain L, Jellinek EH Ball K: Hashimoto’s disease and encephalopathy. Lancet 1966; 2:512–514Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Chong JY, Rowland LP Utiger RD: Hashimoto encephalopathy: syndrome or myth? Arch Neurol 2003; 60:164–171Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Sawka AM, Fatourechi V, Boeve BF, et al: Rarity of encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis: a case series from mayo clinic from 1950 to 1996. Thyroid 2002; 12:393–398Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Boeve BF, Castillo PR, Caselli JR, et al: Steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with thyroid autoimmunity: outcome with immunomodulatory therapy [abstract]. J Neurol Sciences 2001; 187:S441Google Scholar

5 Castillo PR, Boeve BF, Caselli JR, et al: Steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with thyroid autoimmunity: clinical and laboratory findings [abstract]. Neurol 2002; 58:A248Google Scholar

6 Ferracci F, Bertiato G Moretto G: Hashimoto’s encephalopathy: epidemiologic data and pathogenetic considerations. J Neurol Sci 2004; 217:165–168Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 Kothbauer-Margreiter I, Sturzenegger M, Komor J, et al: Encephalopathy associated with hashimoto thyroiditis: diagnosis and treatment. J Neurol 1996; 243:585–593Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Vasconcellos E, Pina-Garza JE, Fakhoury T, et al: Pediatric manifestations of hashimoto’s encephalopathy. Pediatr Neurol 1999; 20:394–398Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Galluzzi S, Geroldi C, Zanetti O, et al: Hashimoto’s encephalopathy in the elderly: relationship to cognitive impairment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2002; 15:175–179Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Chaudhuri A Behan PO: The clinical spectrum, diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment of hashimoto’s encephalopathy (recurrent acute disseminated encephalomyelitis). Curr Med Chem 2003; 10:1945–1953Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Chen HC Marsharani U: Hashimoto’s encephalopathy. South Med J 2000; 93:504–506Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 Henchey R, Cibula J, Helveston W, et al: Electroencephalographic findings in hashimoto’s encephalopathy. Neurol 1995; 45:977–981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Schauble B, Castillo PR, Boeve BF, et al: EEG findings in steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis. Clin Neurophysiol 2003; 114:32–37Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 Nolte KW, Unbehaun A, Sieker H, et al: Hashimoto encephalopathy: a brainstem vasculitis? Neurol 2000; 54:769–770Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Duffey P, Yee S, Reid IN, et al: Hashimoto’s encephalopathy: postmortem findings after fatal status epilepticus. Neurol 2003; 61:1124–1126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Shibata N, Yamamoto Y, Sunami N, et al: Isolated angiitis of the CNS associated with hashimoto’s disease. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 1992; 32:191–198Medline, Google Scholar

17 Peschen-Rosin R, Schabet M Dichgans J: Manifestation of Hashimoto’s encephalopathy years before onset of thyroid disease. Eur Neurol 1999; 41:79–84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Canton A, de Fabregas O, Tintore M, et al: Encephalopathy associated to autoimmune thyroid disease: a more appropriate term for an underestimated condition? J Neurol Sci 2000; 176:65–69Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Ferracci F, Moretto G, Candeago RM, et al: Antithyroid antibodies in the CSF: their role in the pathogenesis of hashimoto’s encephalopathy. Neurol 2003; 60:712–714Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Shaw PJ, Walls TJ, Newman PK, et al: Hashimoto’s encephalopathy: a steroid-responsive disorder associated with high anti-thyroid antibody titers-report of 5 cases. Neurol 1991; 41:228–233Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Forchetti CM, Katsamakis G Garron DC: Autoimmune thyroiditis and a rapidly progressive dementia: global hypoperfusion on spect scanning suggests a possible mechanism. Neurol 1997; 49:623–626Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Latinville D, Bernardi O, Cougoule JP, et al: Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and myoclonic encephalopathy. Pathogenic hypothesis. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1985; 141:55–58Medline, Google Scholar

23 Arain A, Abou-Khalil B Moses H: Hashimoto’s encephalopathy: documentation of mesial temporal seizure origin by ictal EEG. Seizure 2001; 10:438–441Medline, Google Scholar

24 Boers PM Colebatch JG: Hashimoto’s encephalopathy responding to plasmapheresis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001; 70:132Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Henderson LM, Behan PO, Aarli J, et al: Hashimoto’s encephalopathy: a new neuroimmunological syndrome [abstract]. Annals of Neurol 1987; 22:140–141Google Scholar

26 Seipelt M, Zerr I, Nau R, et al: Hashimoto’s encephalitis as a differential diagnosis of creutzfeldt-jakob disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999; 66:172–176Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Doherty CP, Schlossmacher M, Torres N, et al: Hashimoto’s encephalopathy mimicking creutzfeldt-jakob disease: brain biopsy findings. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002; 73:601–602Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 Hernandez Echebarria LE, Saiz A, et al: Detection of 14-3-3 protein in the CSF of a patient with hashimoto’s encephalopathy. Neurol 2000; 54:1539–1540Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 Cossu G, Melis M, Molari A, et al: Creutzfeldt-jakob disease associated with high titer of antithyroid autoantibodies: case report and literature review. Neurol Sci 2003; 24:138–140Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar